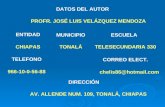

SimSuite

Transcript of SimSuite

P3D

to the patient by the physician and signed prior to the procedure. If this is not done, the physician may not bill the patient for the procedure.

Expected Status Once the FDA has approved a device (stent and/or

embolic protection device) for carotid stenting, Medicare

will be strongly encouraged to change their non-cover

age policy. It is anticipated that a group of specialty

societies that treat patients with carotid disease and

stroke will develop a set of guidelines determining a sub-set of "high-risk" patients. This set of guidelines will

be distributed to carriers to help them identify patients who could and should benefit from carotid stenting. This set of guidelines is intended to help them craft a reason

able coverage policy, from CMS' perspective, patient perspective, and physician perspective.

Cordis Endovascular is expected to submit its data

from the Sapphire trial to the FDA in early October 2003.

It is hoped that FDA-approval could occur in early 2004,

possibly around the time of the annual SIR meeting in Phoenix in March. Because of that anticipation, a coali

tion of physicians from multiple societies (including SIR,

ASITN, ASNR, and ACR) has developed a CPT proposal for carotid stenting, intended for submission to the CPT

Panel in early October 2003. CPT approval of CategOIY I codes with RUC (Relative-value Update Committee) val

uation would be available ]anualY 1, 2005 at the velY

earliest. The structure of those codes will depend on deliberation by the CPT Panel.

Interim Status Once a procedure has been FDA-approved, carriers may decide to cover the procedure (coverage policy). For

Medicare, there is currently a national non-coverage policy, so it is hoped that when the policy is changed, there will be a national coverage policy, which would make coverage uniform throughout the country. This may not happen, however, and CMS may leave it to local carrier discretion to determine coverage.

If the non-coverage policy is changed, it is hoped that the coverage policy will change before the CPT code is officially available, and societies will work with CMS and other carriers as a coalition to determine a uniform pay

ment policy if possible. If a uniform payment policy cannot be made by CMS, the societies will develop a Model Policy for members to use when talking with their

local carriers about the procedure. Model poliCies such as this have been developed for several other procedures where coverage policy has preceded payment

policy. These model poliCies make it easier for physicians to explain the procedure, the work, the value to the

patients, and the value to the physicians to the carriers, facilitating development of a good local policy.

4:35 p.m. Minimum Training Requirements for Carotid Stenting john J. "Buddy" Connors, Ill, MD

Miami Cardiac & Vascular Institute Miami, FL

4:50 p.m. SimSuite

4:55 p.m. Will Simulator Training Be Part of Our Future? Steven L. Dawson, MD The Simulation Group-CIj\1IT Cambl"idge, MA

Reprinted with pennission from the November 2002 issue of the Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons.

The ideas in this syllabus were originally presented as

a keynote address at a workshop on surgical simulation sponsored by the American College of Surgeons, Boston, Massachusetts, April 20-21, 2002.

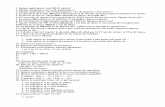

Ten years from now, we will be learning, testing and

re-certifying on medical simulators.

Physicians are justifiably proud of our residency ex

perience, with long days and nights on call treating whoever "comes in the front door". We accept that the

vagaries of illness and accidents will provide us with

enough experience to prepare us for a lifetime of practice. We learn from older faculty members in large academic medical canters, training on rich and poor alike,

but more frequently on the poor or uninsured. This

traditional system dates back to Halsted, but has its origins in the ancient Egyptians, who would apprentice

young boys to a master "mechanical healer", whom we would today call a surgeon. We accept these customs as

necessary rituals of learning. Medicine's traditional methods of learning have been just that- traditional.

Yet physicians must also remain current in the present state of the art and new methods which develop after the end of residency. When Continuing Medical Education was introduced, we maintained our edge by attending didactic lectures or reading journals and answering CME quizzes. Hands-on animal courses proVided us with certificates of attendance that demonstrated competence performing new procedures in radiology cardiology and other procedural specialties. These one or two day animal courses were accepted as valid learning methods for complex new procedures because there was little alternative.

As a result, organized learning of interventional techniques became a cottage industry of weekend pig courses with the experts. The educational role of organized specialty soci

eties diminished.

Why Simulation? Organized medicine had the gauntlet thrown at its feet in 1999, when the Institute of Medicine released its report,

To Err is Human (1). This report, which awakened the general public to the prevalence of medical errors, also challenged medicine to do better. According to this report, at least 44,000 Americans die from medical errors evelY year. In other words, the seventh leading cause of death in this country is being cared for by a physician! As