hrudnick.sitios.ing.uc.clPONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA MECANISMOS...

Transcript of hrudnick.sitios.ing.uc.clPONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA MECANISMOS...

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE

ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA

MECANISMOS PARA LA INVERSIÓN Y

REMUNERACIÓN DE LA TRANSMISIÓN

DE ENERGÍA ELÉCTRICA

JUAN DAVID MOLINA CASTRO

Tesis para optar al grado de

Doctor en Ciencias de la Ingeniería

Profesor Supervisor:

HUGH RUDNICK VAN DE WYNGARD

Santiago de Chile, julio, 2012.

2012, Juan David Molina Castro

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE

ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA

MECANISMOS PARA LA INVERSIÓN Y REMUNERACIÓN DE LA TRANSMISIÓN DE

ENERGÍA ELÉCTRICA

JUAN DAVID MOLINA CASTRO

Tesis presentada a la Comisión integrada por los profesores:

HUGH RUDNICK VAN DE WYNGARD

RICARDO RAINERI BERNAIN

JUAN MANUEL ZOLEZZI CID

JUAN CARLOS ARANEDA TAPIA

JAVIER CONTRERAS SANZ

CRISTIAN VIAL EDWARDS

Para completar las exigencias del grado de

Doctor en Ciencias de la Ingeniería

Santiago de Chile, julio, 2012.

ii

A Sarah Sofía y Milena, por su amor

y tiempo para poder desarrollar este

proyecto de vida…

iii

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Esta investigación es el resultado de la dedicación y acompañamiento de personas,

amigos y colegas, que aportaron su conocimiento para generar, analizar y evaluar los

métodos y herramientas desarrolladas.

Sin lugar a duda, agradezco el apoyo incondicional de mi tutor, el profesor Hugh

Rudnick, su confianza y disposición absoluta, podría decirse que omnipresente, fue la

brújula que me permitió alcanzar los objetivos propuestos en esta investigación, no solo

en el ámbito profesional, sino también a nivel personal, ha sido un privilegio contar con

su conocimiento.

Agradezco a los profesores Marcos Singer, Enzo Sauma y Javier Contreras por

instruirme en las temáticas de teoría de juegos y diseño de mecanismos, en especial a

Javier por su apoyo incondicional durante el desarrollo de la pasantía de investigación.

Agradezco al ingeniero Juan Carlos Araneda por su apoyo y respaldo para ejecutar la

investigación propuesta. Al igual, que al programa de financiación de la Pontificia

Universidad Católica de Chile (DIPEI, VRI), el programa MECESUP(2), TRANSELEC

S.A. y el programa en Energías del Ministerio de Energía y CONICYT.

Agradezco, al personal del DIPEI por su apoyo y asesoría en los temas de doctorado, la

subdirectora Fernanda Kattan, Debbie y Jorge.

A mis compañeros de oficina Victor y German y del departamento de ingeniería

eléctrica, Hernán, Marisol, Roberto, Carlos y la colonia colombiana de ingeniería por

compartir sus experiencias.

Agradezco al departamento de ingeniería eléctrica, al profesor Sebastián Ríos y al

personal administrativo por su apoyo en los temas cotidianos, las damas Jessica, Betty,

Giannina, Virginia y el señor Carlos.

Finalmente, agradezco a mi señora madre por su formación y apoyo incondicional para

llevar a cabo todas mis metas propuestas.

INDICE GENERAL

Pág.

DEDICATORIA ............................................................................................................... ii

AGRADECIMIENTOS ................................................................................................... iii

INDICE DE TABLAS ..................................................................................................... vi

INDICE DE FIGURAS ................................................................................................... vii

1. INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Problemática y antecedentes ........................................................................... 1

1.2 Objetivo de la investigación ............................................................................ 3

1.3 Hipótesis de la investigación ........................................................................... 3

1.4 Estado del arte ................................................................................................. 4

1.5 Metodología .................................................................................................... 6

1.6 Resultados de la investigación ...................................................................... 11

1.7 Publicaciones ................................................................................................. 13

1.8 Organización de la tesis ................................................................................ 16

2. EXPANSIÓN DE LA TRANSMISIÓN ................................................................ 18

2.1 Modelos para la planificación de la expansión ............................................. 18

2.1.1. Modelo centralizado ............................................................................ 18

2.1.2. Modelo descentralizado ...................................................................... 19

2.2. Incentivos para la inversión ............................................................................ 21

2.2.1. Incentivos regulatorios ........................................................................ 21

2.2.2. Incentivos de mercado ......................................................................... 22

2.2.3. Incentivos híbridos .............................................................................. 23

2.3. Desafíos en la expansión ................................................................................ 24

2.3.1. Buenas prácticas .................................................................................. 24

2.3.2. Anomalías ........................................................................................... 25

2.3.3. ¿Existe un óptimo? .............................................................................. 26

2.3.4. Flujo variable y asignación de costo ................................................... 30

2.3.5. Expansión de la red y energías renovables ......................................... 32

3. MECANISMOS E INCENTIVOS: EL JUEGO DE LA EXPANSIÓN ............... 38

3.1. Planes de expansión ...................................................................................... 40

3.2. Valor esperado de un plan de expansión ....................................................... 44

3.3. Portafolio óptimo de inversión ...................................................................... 48

3.4. Desarrollo de la expansión: asignación de costo y aceptabilidad ................... 51

3.5. Clasificación de un plan de expansión ........................................................... 56

4. CASOS DE ESTUDIO .......................................................................................... 61

4.1. Plan multi-objetivo: Sistema IEEE 24-RTS .................................................. 61

4.2. Plan pre-definido: Sistema SIC-55 ................................................................ 68

5. CONCLUSIONES ................................................................................................. 74

5.1. Contribuciones .............................................................................................. 75

5.2. Desarrollos futuros ........................................................................................ 81

BIBLIOGRAFÍA ............................................................................................................ 82

A N E X O S ................................................................................................................... 86

Anexo A: Transmission of Electric Energy: A Bibliographic Review ........................... 87

Anexo B: Multi-Objective Transmission Expansion Planning: Linking Energy Planning

Goals and Ordinal Meta-Heuristic Optimization............................................ 88

Anexo C: A Principal-Agent Approach to Transmission Expansion - Part I: Regulatory

Framework ...................................................................................................... 89

Anexo D: A Principal-Agent Approach to Transmission Expansion - Part II: Case

Studies .......................................................................................................... 90

Anexo E: A Risk-Constrained Project Portfolio in Transmission Investment ................ 91

Anexo F: Approaches to transmission planning: a transmission expansion game ......... 92

vi

INDICE DE TABLAS

Pág.

Tabla 2-1: Comparación de modelos de transmisión ........................................................... 29

Tabla 3-1: Tipo de plan de expansión (topología) ............................................................... 58

Tabla 3-2: Tipo de plan de expansión (ejecución) ............................................................... 59

Tabla 3-3: Clasificación de un plan de expansión ............................................................... 60

Tabla 4-1: Planes de expansión: sistema 24 RTS-IEEE ...................................................... 62

Tabla 4-2: Parámetros de los inversionistas ......................................................................... 63

Tabla 4-3: Valor de oferta de un plan de expansión ............................................................ 63

Tabla 4-4: Valor plan adaptado ............................................................................................ 64

Tabla 4-5: Impacto del riesgo en plan diverso ..................................................................... 64

Tabla 4-6: Valor oferta plan diverso sin costo de servidumbre ........................................... 65

Tabla 4-7: Valor oferta plan adaptado sin costo de servidumbre ......................................... 65

Tabla 4-8: Percepción de aceptación de un plan de expansión ............................................ 66

Tabla 4-9: Valor oferta plan sustentable-aceptable .............................................................. 67

Tabla 4-10: Valor oferta con factor de reconocimiento de costo ......................................... 67

Tabla 4-11: Valor esperado de un plan de expansión por tipo ............................................. 68

Tabla 4-12: Parámetros plan de expansión pre-definido...................................................... 69

Tabla 4-13: Parámetros de tipo de inversionistas ................................................................ 70

Tabla 4-14: Valor esperado plan pre-definido con costo servidumbre ................................ 71

Tabla 4-15: Portafolio de inversión con costo de servidumbre............................................ 71

Tabla 4-16: Valor esperado plan pre-definido sin costo servidumbre ................................. 72

Tabla 4-17: Portafolio de inversión sin costo de servidumbre ............................................. 72

Tabla 4-18: Portafolio de inversión con reconocimiento de costo (α) ................................. 73

Tabla 4-19: Comparación de valor esperado del plan pre-definido ..................................... 73

vii

INDICE DE FIGURAS

Pág.

Figura 2-1: Filosofías de expansión. .................................................................................... 26

Figura 3-1: Metodología de evaluación de planes expansión. ............................................. 39

Figura 3-2: Metodología para identificar planes de expansión. ........................................... 45

Figura 3-3: Metodología de asignación de costo de la transmisión renovable .................... 52

Figura 3-4: Encuesta tipo para evaluar el impacto de un proyecto ...................................... 55

Figura 3-5: Histograma de probabilidad de aceptación de un proyecto de expansión ......... 56

Figura 3-6: Clasificación de un plan de expansión .............................................................. 57

Figura 4-1: Sistema 24 RTS-IEEE. ...................................................................................... 66

viii

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA

MECANISMOS PARA LA INVERSIÓN Y REMUNERACIÓN DE LA TRANSMISIÓN DE ENERGÍA ELÉCTRICA

Tesis enviada a la Dirección de Investigación y Postgrado en cumplimiento parcial de

los requisitos para el grado de Doctor en Ciencias de la Ingeniería.

JUAN DAVID MOLINA CASTRO

RESUMEN La evolución del mercado de energía y la creciente participación de los agentes en el negocio de la transmisión de energía han traído consigo una mayor complejidad para definir qué expandir en un sistema de transmisión y cómo decidir un plan de expansión. Las metodologías de expansión se sostienen bajo principios de cooperación y bajo este principio se han propuesto varias alternativas para su desarrollo. Sin, embargo, los agentes participantes en la expansión de la transmisión son racionales y como tal maximizan su utilidad. Esto hace necesario evaluar mecanismos de acoplamiento entre conceptos económicos y técnicos con la finalidad de brindar soluciones claras y transparentes para el desarrollo del mercado eléctrico.

El objetivo de la investigación es diseñar un mecanismo que incentive la expansión de la transmisión considerando la maximización del beneficio social, la estructura del mercado y el comportamiento de los agentes. Se propone una metodología de expansión de la transmisión, un juego, que consta de cuatro elementos principales: i) la generación de alternativas de planes de expansión de la transmisión, ii) la valoración de proyectos con base en el diseño de contrato lineales, soluciones de negociación y el modelo de principal-agente, iii) el valor óptimo de un portafolio de inversión desde la perspectiva de un inversionista privado y iv) la aceptabilidad y asignación de costo de los proyectos de expansión.

El documento de tesis presenta un análisis de los mecanismos utilizados para la expansión e inversión de la transmisión, los modelos económicos utilizados para el análisis de la transmisión, las técnicas de programación matemática y heurísticas para implementar un algoritmo de planificación meta-heurístico, los fundamentos teóricos de diseño de mecanismos y juegos y el desarrollo de casos de estudio.

El aporte de la investigación doctoral se enfoca en identificar las anomalías de la planificación de la expansión, el impacto de los incentivos implementados para la inversión y la asignación de costos de la transmisión, la implementación de un mecanismo de expansión en función del beneficio de los agentes, la caracterización de los conflictos entre los agentes interesados en la expansión y la efectividad de la cooperación (qué expandir y cómo decidir) mediante un mecanismo no-cooperativo. Las

ix

herramientas y modelos desarrollados brindan elementos de juicio para el diseño de normativa y la evaluación del comportamiento estratégico de un inversionista bajo las consideraciones del mercado eléctrico.

Los resultados muestran que determinar cuáles son las características de cada inversionista, inferir su nivel de esfuerzo y su capacidad para disminuir los costos conllevan a la asignación eficiente de un proyecto. Esto se debe a que el costo óptimo de un proyecto está condicionado por la capacidad de negociación de un inversionista con terceros. Además, se identifica como el nivel de competencia, el incentivo de reconocimiento de costo y el riesgo que determina cada inversionista influyen en el desarrollo del plan de expansión de transmisión. Un aspecto relevante a considerar es que si bien pueden participar inversionistas "ideales" en el proceso de asignación de un proyecto, sus restricciones individuales, rentabilidad, presupuesto, valoración del riesgo, entre otros, implican un comportamiento estratégico en los procesos de adjudicación de proyectos. Esto conlleva a que se presenten ofertas no-óptimas en aquellos proyectos donde la participación de inversionistas "ideales" sea restringida.

Se concluye que las técnicas meta-heurísticas son una herramienta eficaz para resolver el problema combinatorial. La compatibilidad de incentivos de los agentes permitirá un proceso coordinado para ejecutar oportunamente la expansión. El mecanismo con base en un juego no-cooperativo define las reglas de compatibilidad de incentivos y revelación de información que mitigan la incertidumbre que caracterizan la expansión. La cuantificación del riesgo determina el límite de participación de los inversionistas y se identifica que tipo de proyectos podrán ejecutarse eficientemente. A su vez, el desarrollo de las tecnologías que influyen en la transmisión, condicionan la racionalidad de los agentes, no solo en la planificación, sino, en la aceptación y asignación de costo que permita el desarrollo de la transmisión.

Los desarrollos futuros sobre los cuales se considera relevante profundizar son: el problema de la dimensionalidad de alternativas de expansión y negociación multi-agente, implementar técnicas de referenciamiento "benchmarking" para caracterizar a los agentes inversionistas, realizar encuestas in-situ para determinar estrategias y preferencias de los agentes que participan en el proceso de planificación. Finalmente, implementar la metodología propuesta en otras áreas de la planificación de redes o infraestructura. Miembros de la Comisión de Tesis Doctoral HUGH RUDNICK VAN DE WYNGARD RICARDO RAINERI BERNAIN JUAN MANUEL ZOLEZZI CID JUAN CARLOS ARANEDA TAPIA JAVIER CONTRERAS SANZ CRISTIAN VIAL EDWARDS Santiago, julio, 2012

x

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DE CHILE ESCUELA DE INGENIERIA

MECHANISMS TO ENCOURAGE INVESTMENT OF TRANSMISSION EXPANSION PLANS

Thesis submitted to the Office of Research and Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Engineering Sciences by

JUAN D. MOLINA

ABSTRACT

The evolution of the energy market and the growing participation of the agents involved in the transmission business have generated a greater complexity in the definition of how to expand the transmission system and how to choose an expansion plan. Expansion methodologies are supported under cooperative principles and under this principle several alternatives have been proposed for their development. However, the agents involved in the transmission expansion are rational and profit maximizers. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate coupling mechanisms between economic and technical concepts that provide clear and transparent solutions for the development of the energy market.

The objective of this research is to design a mechanism that encourages the transmission expansion considering the maximization of social welfare, the structure of the market and the behavior of the agents. A methodology is proposed for transmission expansion, a game, which has four main elements: i) generation of alternatives of transmission expansion plans, ii) valuation of projects based on design mechanisms and linear contracts, bargaining solutions and the principal-agent model, iii) the optimal investment portfolio from the perspective of a private investor and iv) the acceptability and cost allocation of expansion projects.

The thesis presents an analysis of the mechanisms used for transmission investment and expansion, the economic models used to analyze transmission, the mathematical programming and heuristic techniques to implement a meta-heuristic algorithm for the transmission expansion problem, the theoretical fundamentals of mechanism design and game theory and the development of case studies.

The contribution of the doctoral research focuses on identifying anomalies of planning methodologies, the impact of investment incentives and cost allocation of transmission projects, the implementation of mechanism based on the benefit of agents, the characterization of the conflicts between the agents interested in the expansion and the effectiveness of cooperation (what to expand and how to decide) by a non-cooperative mechanism. The developed tools and models provide evidence for the design of rules

xi

and the evaluation of the strategic behavior of an investor under the energy market context.

Results show that determining the investor characteristics, infer its effort level and ability to reduce costs, lead to an efficient allocation process. This is because the optimal cost of a project is conditioned by the bargaining power of the investor with third parties. Furthermore, we identify how the competition level, the incentive to recognize cost incentive and the risk determined by each investor, influence the development of the transmission expansion plan. An important aspect to consider is that while "ideal" investors can participate in the project allocation process, their individual constraints, profitability, budget, risk assessment, among others, imply a strategic behavior in the process. This results in non-optimal bids for those projects which have a restricted participation of “ideal” investors.

We conclude that meta-heuristic techniques are effective tools to solve the combinatorial problem. The incentive compatibility of the agents allows a coordinated process for the timely expansion. The mechanism, based on a non-cooperative game, defines the incentive compatibility rules and the disclosure of information to mitigate the uncertainty that characterizes the expansion. The quantification of risk determines the participation limit of investors and identifies what types of projects may be implemented efficiently. In turn, the development of the technologies that influence transmission condition the rationality of the agents, not only in planning, but in the acceptance and cost allocation to enable the transmission development.

Future developments considered relevant are: the problem of dimensionality (combinatorial problem) of expansion alternatives and multi-agent negotiation, implementation of benchmarking techniques to characterize the investment agents, on-site surveys to determine strategies and preferences of agents involved in the planning process. Finally, implement the proposed methodology in other areas of network or infrastructure planning.

Members of the Doctoral Thesis Committee: HUGH RUDNICK VAN DE WYNGARD RICARDO RAINERI BERNAIN JUAN MANUEL ZOLEZZI CID JUAN CARLOS ARANEDA TAPIA JAVIER CONTRERAS SANZ CRISTIAN VIAL EDWARDS Santiago, july, 2012

1

1. INTRODUCCIÓN

Las metodologías de expansión se sostienen bajo el principio de cooperación y bajo este

principio se propopen alternativas para su desarrollo. Sin, embargo, los agentes

participantes en la expansión de la transmisión son racionales y como tales maximizan

su utilidad. Las diferentes reformas llevadas a cabo en el mundo muestran que a nivel

regulatorio se diseñan mecanismos de acoplamiento entre conceptos económicos y

técnicos con la finalidad de brindar soluciones claras y transparentes para el mercado

eléctrico. Los mecanismos e incentivos se focalizan en la búsqueda de la inversión

óptima y la operación eficiente bajo criterios de costos, confiabilidad, competencia del

mercado, sustentabilidad y beneficio de los agentes.

En el mercado de energía implementado en Chile, en particular el sector eléctrico en

Chile, se pasó de un modelo de expansión de la transmisión descentralizado a uno

centralizado con el objetivo de mejorar las fallas que presentaba la metodología

existente (Rudnick, Araneda & Mocarquer, 2009). Sin embargo, la metodología actual

evidencia limitaciones al no poder capturar la dinámica que se presenta en este sector.

Además, la promulgación de leyes ambientales y la coyuntura político-social, hacen que

la metodología de qué expandir y cómo decir sea un problema relevante para el mercado

eléctrico. La interpretación equivocada de las señales del entorno, el mercado, el ente

regulador, la competencia o las propias empresas puede conducir a la selección de

estrategias, objetivos y acciones sub-óptimas.

1.1 Problemática y antecedentes

Bajo los conceptos de la economía clásica las instituciones reguladoras conciben

conceptos de eficiencia y equidad, pero sin establecer claramente el beneficio

social. Los principios de eficiencia y equidad son incompatibles (Zheng, Zhang, &

Hou, 2006) y el óptimo social difiere del óptimo individual, tanto en estructuras de

monopolio regulado como con base en las señales del mercado (Fonseka &

Shrestha, 2004). Esto muestra que las anomalías o incentivos perversos que

2

puedan presentarse dependerán de la metodología utilizada. La transmisión, al ser

considerada como un monopolio natural y por tanto regulada, dependerá de los

mecanismos (señales eficientes) implementados por el regulador para el desarrollo

óptimo de la transmisión (la maximización del bienestar social del usuario y de la

utilidad del transportador).

Uno de los aspectos que más se destaca en el desarrollo y planificación del sector

eléctrico es que la expansión de la capacidad en generación no se ha acompañado

de la expansión de la transmisión. Esto muestra que los mecanismos creados para

realizar la expansión no han sido prácticos para estimular la inversión (CEPAL,

2005) y las denominadas instalaciones esenciales se han constituido como “cuellos

de botella” en servicios de infraestructura.

Además, la incertidumbre que se presenta en los flujos de potencia, los problemas

asociados a las economías de escala, riesgo y detrimento de las inversiones por la

utilización de tecnologías que controlen los flujos de potencia (HVDC/FACTS)

(Brunekreeft, 2003) y los conflictos de interés que se presentan entre los agentes

del mercado (Shrestha & Fonseka, 2005) son aspectos que la regulación no aborda

en su totalidad.

A nivel mundial, los incentivos regulatorios se enfocan en la reducción de costos,

el mejoramiento de la calidad del servicio y el estímulo a la inversión y precios

eficientes de acceso a la red (Joskow, 2005). Adicionalmente, debido a los

diversos “Black-out” ocurridos a nivel mundial se han revaluado los conceptos de

regulación económica y la incidencia de la confiabilidad para la inversión en

transmisión, así como la consideración de operadores independientes y/o

regionales de la transmisión. Sin embargo, es un tema abierto, principalmente en

países con tasas representativas de crecimiento de la demanda, entre ellos los

países de Sudamérica.

3

1.2 Objetivo de la investigación

El objeto de la investigación es diseñar un mecanismo que incentive la expansión

de la transmisión considerando la maximización del beneficio social, la estructura

del mercado y el comportamiento de los agentes.

Básicamente, se consideran 6 objetivos específicos:

1. Analizar los mecanismos utilizados para la expansión e inversión de la

transmisión.

2. Analizar los modelos económicos utilizados en el negocio de la transmisión.

3. Analizar técnicas de programación matemática y heurísticas para

implementar un algoritmo de planificación meta-heurístico en la transmisión.

4. Desarrollo e implementación de la teoría de diseño de mecanismos para

incentivar la expansión de la transmisión.

5. Diseñar un mecanismo que identifique y evalúe las estrategias y

comportamientos de los agentes del mercado.

6. Dar a conocer a la comunidad científica los resultados obtenidos mediante la

publicación de la investigación.

1.3 Hipótesis de la investigación

Para el desarrollo de la presente investigación se consideran las siguientes

hipótesis de trabajo:

- Los agentes participantes en la expansión de la transmisión son racionales

con intereses individuales (preferencias heterogéneas) y como tal maximizan

su utilidad.

- Los incentivos regulatorios condicionan los planes de expansión de la

transmisión.

- La metodología utilizada para definir el Sistema de Transmisión Troncal

influye en la eficiencia técnica y económica del sistema eléctrico.

4

Esta hipótesis de trabajo nos permite formular la principal hipótesis de

investigación:

mediante un juego no-cooperativo y con mecanismos con base en la incertidumbre

es posible obtener incentivos óptimos para el desarrollo eficiente de la expansión

de la transmisión y la maximización del beneficio social.

1.4 Estado del arte

La evolución de los mercados de energía muestra que los intereses de los agentes

son conflictivos para determinar la expansión óptima del sistema. Esto varía en

función del tipo de estructura de mercado y/o el marco regulatorio para la

expansión del sistema de transmisión. Desde el punto de vista económico, los

modelos oligopólicos describen estos intereses. Por ejemplo, en el caso de

interconexión de sistemas, la capacidad o flujo de la línea de transmisión

disminuye a medida que se incrementa la capacidad de inyección de la generación.

Esto crea conflictos en la planificación sobre la capacidad de diseño de la línea de

transmisión y la indivisibilidad de las inversiones. A su vez, desde el punto de

vista social, la capacidad de la línea debería ser la mayor posible lo que genera

conflicto de interés entre los generadores. Además, se establece que el

comportamiento del transportador, dependiente de los pagos de la congestión,

presenta una respuesta de baja capacidad (Shrestha & Fonseka, 2007). En la

práctica, las líneas no se financian estrictamente por estas rentas. Por tanto, se

determinará la una capacidad mínima y su respectivo valor que financie en su

totalidad el costo de la línea. Adicionalmente, se genera un dilema respecto a que

si la estructura de mercado refleja la inversiones de capacidad necesarias del

sistema y el momento de éstas, es decir si la expansión debe darse de forma

proactiva (E. E. Sauma & Oren, 2006). Se genera un problema de anticipación

entre la expansión de líneas de transmisión y la inclusión de nueva generación.

Este tipo de comportamiento trae una alta incertidumbre, porque si bien, desde el

punto social es más eficiente, la anticipación acarrea un costo y riesgo respecto a si

5

se construye o no una central de generación (Rious, Glachant, & Dessante, 2010;

E. Sauma, Traub, & Vera, 2010).

En la literatura (Molina & Rudnick, 2010a), se encuentran diversas formas de

proponer el modelo económico bajo el cual se lleva a cabo la expansión.

Generalmente, se caracterizan los agentes según su función objetivo o interés en la

expansión mediante la definición de estrategias y pagos, la definición del tipo de

modelo oligopólico y las etapas de negociación (repetición del juego). Además,

dependiendo de la característica del mercado se utilizan modelos económicos tales

como, Cournot, Bertrand y Stackelberg para llevar a cabo la inversión en

transmisión. Estas metodologías se pueden concebir como un juego entre agentes,

en nuestro caso, lo concebimos como el juego de expansión de la transmisión.

Existen diversas formas de proponer el juego de expansión de la transmisión

(Sauma & Oren, 2006; Serrano, et al, 2007; Contreras, et al, 2009; Hesamzadeh,

et al, 2009a, Hesamzadeh, et al, 2009b; Rious, et al, 2010;). En nuestro caso, se

asume que el tipo de mercado eléctrico se rige bajo la oferta y la demanda de

capacidad (MW). Por tanto, se consideran los modelos con base en la cantidad, es

decir, la interacción estratégica de agentes se da bajo los modelos estáticos de

Cournot y Stackelberg (Vega-Redondo, 2003). En el caso del modelo de Cournot

se establece un juego de cantidad en el que se determina su equilibrio, por

ejemplo, un equilibrio Nash-Cournot (Molina, et al, 2010). En el caso del modelo

de Stackelberg, se establece un juego secuencial de dos etapas, el líder establece

una cantidad y los seguidores establecen su cantidad óptima en función de la

cantidad.

¿Cuál es el juego de la transmisión?, esto sin lugar a duda depende de la

metodología del proceso de planificación, quiénes toman las decisiones y cuáles

agentes y cómo estos pueden influir en el plan de expansión de la transmisión. Se

considera que la planificación la realiza un planificador social o coordinador, el

cual es el responsable de recibir y coordinar las diferentes propuestas de

expansión. Básicamente, el planificador social define un plan bajo criterios de

6

seguridad (criterio N – n), eficiencia económica (métricas de congestión del

sistema) y suficiencia y diversidad de los recursos energéticos (margen de reserva,

energías renovables,…).

En la actualidad, los criterios básicos a considerar en la planificación de la

expansión de la transmisión deben considerar lo siguiente: mejoramiento de la

confiabilidad, incremento de la disponibilidad de suministro y el incremento de la

competencia de los agentes del mercado. Además, se deben diseñar mecanismos

con base en incentivos que maximicen el beneficio social y la representación de

escenarios más reales (representación de la generación, transmisión y demanda)

que determinen la inversión óptima del sistema de transmisión (Contreras, Gross,

Arroyo, & Munoz, 2009), la identificación de los riesgos más relevantes en la

planeación de la transmisión (Varadan & van Casteren, 2009) y la incidencia de

estos en la expansión del sistema (Li, McCalley, & R, 2008; Zhang, Graham, &

Ramsay, 2009). Dada la dinámica que se presenta en las investigaciones respecto a

la transmisión (J. D. Molina & H. Rudnick, 2010), (J.D. Molina & H. Rudnick,

2010)(J.D. Molina & H. Rudnick, 2010)(J.D. Molina & H. Rudnick, 2010)(J.D.

Molina & H. Rudnick, 2010)(J.D. Molina & H. Rudnick, 2010)(Wagner, 2004), en

el Anexo A se presenta una revisión bibliográfica.

1.5 Metodología

La metodología de expansión se establece bajo el concepto de diseño de

mecanismos e incentivos. Un estudio como el propuesto aporta tres elementos a

saber: influencia de la red y su expansión sobre el comportamiento de los agentes,

la efectividad de la cooperación de un plan de expansión bajo un mecanismo no-

cooperativo y la incidencia sobre la regulación. Las herramientas y modelos

desarrollados brindan elementos de juicio para el diseño de normativa y la

evaluación del comportamiento estratégico de un transportador de energía eléctrica

bajo las consideraciones del mercado eléctrico.

7

Cabe resaltar que el marco conceptual utilizado en el diseño de la metodología está

sujeto a la filosofía de expansión y bajo la lógica establecida en el mercado de

energía en Chile. No es posible identificar o definir un plan de expansión "ideal" o

"benchmark" de referencia con el cual comparar los resultados de la investigación,

no hay en la literatura un patrón que pudiera ser útil a estos efectos, que no sólo

considere las métricas tradicionales de costo sino también métricas que reflejen las

externalidades que se presentan en el mercado de energía y la sociedad respecto al

desarrollo óptimo de un plan de expansión. En ese sentido la investigación

propuesta se enmarca bajo los lineamientos de costos de operación del sistema

eléctrico, inversión de la expansión, emisiones CO2, diversidad de suministro

eléctrico, racionalidad y riesgo de inversión, asignación de costo de la expansión y

aceptabilidad de un proyecto de expansión. Estos lineamientos acotan el plan de

expansión "ideal" y bajo este se determina el comportamiento de los agentes y el

valor y factibilidad de alternativas de expansión. El debate acerca de cuál es el

mecanismo óptimo para la expansión aún se mantiene vigente. La metodología y

enfoque utilizado en la investigación justamente buscan hacer un aporte a la

discusión científica en la materia a nivel internacional.

La investigación considera cuatro fases metodológicas. En la primera, se hace una

revisión de mecanismos desarrollados para la expansión e inversión de la

transmisión. En la segunda, se realiza un análisis de algoritmos para la solución

del problema combinatorial de la expansión. En la tercera, se propone un modelo

con base en el diseño de mecanismos y juegos no-cooperativos para incentivar la

inversión de los proyectos de transmisión. Finalmente, se implementan dos casos

de estudio para: evaluar estrategias e incentivos que utilicen los agentes, evaluar su

impacto sobre el beneficio social y su impacto para diferentes estructuras de la

transmisión.

8

Fase I: Mecanismos para la expansión de la transmisión

Consiste en el análisis de los diferentes mecanismos desarrollados para la

expansión e inversión de la transmisión para identificar y clasificar anomalías de

estos mecanismos. Se definieron tres áreas marco para realizar la investigación:

mecanismos de regulación y mercado, técnicas de modelación económica y

técnica de la red y sistemas de transporte y aplicaciones de mecanismos. Lo

anterior establece la forma en que se ha abordado el problema desde la literatura

científica. Básicamente, esta Fase utiliza métodos de búsqueda bibliográfica para

la obtención y análisis de información de las bases de datos disponibles en la

Universidad y es el insumo para la Fase II.

El desarrollo de esta fase muestra que las reformas llevadas a cabo en los diversos

mercados de energía asignan un lugar central a la transmisión y por tanto esto ha

generado un área de investigación dinámica. Son diversos los tópicos de

investigación, por lo que se requiere identificar las diferentes áreas y avances

científicos en la materia. Esto define los tipos de supuestos utilizados en los

modelos y la influencia de variables dinámicas, tales como la generación, la

demanda y el flujo controlable, y permite una mejor comprensión de la dinámica

del mercado. Se realiza una revisión bibliográfica y bajo un contexto de mercado

de energía se analizan las investigaciones más recientes y relevantes en la

evolución de la transmisión (Anexo A).

Fase II: Algoritmo de planificación de la expansión de la transmisión

Consiste en el análisis de métodos y técnicas implementados para la solución del

problema y modelación de casos bases de la literatura para realizar la planificación

de la expansión de la transmisión. Se implementa la técnica meta-heurísticas

búsqueda tabú y algoritmos de optimización ordinal y multi-objetivo para

identificar la solución de la expansión en transmisión y determinar planes de

expansión. Se utilizan herramientas de software, MATLAB y GAMS ,

9

para modelación de casos referencia de estudio, al igual que herramientas que

existan para la sensibilización del algoritmo.

Básicamente, se desarrolla un modelo de planificación meta-heurística y se define

una metodología para definir alternativas de expansión del sistema de transmisión.

Se propone un modelo que considera la Optimización Ordinal (OO) para generar

espacios de búsqueda de expansiones y la Optimización Multi-objetivo (OMO),

bajo conceptos de óptimo de Pareto y el método ponderado, para identificar

soluciones Elite, soluciones que pertenecen a la frontera de Pareto y la más

cercana al origen bajo un enfoque de optimización min-min. A partir de estas

soluciones Elite-Pareto se implementa una meta-heurística bajo un enfoque de

Búsqueda Tabú (BT) multi-objetivo. Se identifican soluciones mediante el

encadenamiento de trayectorias de las soluciones Elite-Pareto y el criterio de min-

max para identificar soluciones factibles bajo un enfoque de confiabilidad, N-1. El

modelo propuesto genera planes de expansión bajo un enfoque de óptimo de

Pareto. Se identifican soluciones de Pareto considerando lineamientos de la

planificación energética: diversificación y reducción de emisiones CO2 de la

matriz de energía y la anualidad de los costos de operación e inversión con

criterios de seguridad (Anexo B).

Fase III: Modelos de diseño de mecanismos e incentivos

En esta de desarrolla conceptualmente las características físicas y económicas de

la transmisión para evaluar y validar supuestos utilizados en la literatura de

mecanismos para la expansión e inversión de la transmisión. Se diseña un

mecanismo en el cual se defina un juego con sus respectivas reglas que provean

los incentivos apropiados para el desarrollo óptimo del negocio de la transmisión.

En particular, se considera la teoría de juegos con información incierta y/o

incompleta, técnicas de equilibrio de Nash Bayesiano y subastas. En esta Fase, se

desarrollan los conceptos de principio de revelación y compatibilidad de

incentivos, los mecanismos de estrategias dominantes, la racionalidad individual y

10

la factibilidad al considerar restricciones técnicas en la transmisión y la

maximización del beneficio social (Anexo C).

Al considerar que los agentes participantes en la expansión de la transmisión son

racionales, y como tal maximizan su utilidad, nos indica que el proceso de toma de

decisiones debe considerar tanto comportamientos cooperativos como no-

cooperativos para decidir la expansión que requiere el sistema. Para esto la

metodología considera la compatibilidad de incentivos de los agentes para

determinar una valoración óptima y eficiente de la expansión. El modelo descrito

combina el modelo de Principal-Agente con el modelo de competencia de ofertas

(subasta). De esta forma se define un contrato óptimo que considera el riesgo

moral, acción oculta (probabilidad de cierta acción tomada por el agente del

conjunto de acciones posibles), selección adversa, información oculta (costo del

esfuerzo del agente para llevar a cabo una acción) y la valoración real acerca de un

proyecto en función del número de oferentes (Anexo D - Anexo E).

Fase IV: Casos de estudio

En esta fase, se implementa la metodología propuesta para evaluar sus

características en los casos de referencia, evaluar su impacto sobre el beneficio

social y su impacto en la estructura del mercado y el comportamiento de los

agentes. Se consideran escenarios para la expansión de la red. Se utilizan

herramientas de software para su modelación (MATLAB – GAMS ). Se

define una metodología para definir alternativas de expansión de un sistema de

transmisión. Se propone un modelo de expansión de la transmisión, un juego, que

consta de cuatro elementos principales: i) la generación de escenarios del plan de

expansión de la transmisión, ii) la valoración de un proyecto con base en el diseño

de contrato lineales, soluciones de negociación y el modelo principal-agente, iii) el

valor óptimo de un portafolio de inversión de agentes privados, y iv) la asignación

del costos de los activos de transmisión (Anexo F).

11

1.6 Resultados de la investigación

La evolución de los mercados e individualización de los agentes participantes en la

expansión generan una mayor complejidad para determinar el óptimo de qué

expandir y cómo decidir. Generalmente, la eficiencia en el plan de inversión se

soporta en el mínimo costo. Sin embargo, la definición de un mercado de energía

trajo consigo una mayor complejidad. La consideración de diferentes criterios,

tales como técnicos, económicos, financieros o ambientales implica que definir un

conjunto alternativas de expansión y la manera de decidir respecto a cuál es la

óptima sea una ardua tarea. Por ejemplo, metodologías que se rigen

primordialmente por criterios de seguridad hacen redundantes las inversiones y en

el caso de modelos con generadores dominantes estas son las mínimas posibles.

Un aspecto a resaltar, es evaluar la viabilidad o la estabilidad en la ejecución de un

plan óptimo de expansión de la transmisión. En las últimas décadas, se ha

incrementado el tiempo de construcción de los activos de transmisión, los costos

de negociación por servidumbre y el rechazo a proyectos tanto de generación

como en la transmisión. Esto ha dado lugar a retrasos inevitables y aumento de

costos en el mercado de energía. Este aspecto no ha sido considerado en las

investigaciones y en esta línea de investigación se enfoca el aporte de la presente

tesis de investigación. A continuación, se presentan los resultados:

a) Fase I: Las experiencias son diversas y varían en función del grado de

configuración, propiedad, tarificación y procesos de planificación de la

transmisión (actores principales). Los nuevos avances regulatorios se

concentran en el desarrollo de la red de transmisión dedicada u orientada a las

energías renovables. Al igual, que enlaces HVDC en el contexto de mercado

para interconectar países y/o operadores. La investigación propone

mecanismos de acoplamiento entre conceptos económicos y técnicos, con la

finalidad de brindar soluciones factibles para el mercado eléctrico.

12

b) Fase II: El modelo propuesto para generar planes de expansión bajo un

enfoque de óptimo de Pareto presenta soluciones aceptables bajo criterios de

robustez y rapidez algorítmica. Los resultados obtenidos en los sistemas de

prueba muestran que el modelo desarrollado es efectivo para la solución del

problema combinatorial. La optimización multi-objetivo define un conjunto

de soluciones factibles que establecen escenarios de planes de expansión

sustentables. El método de optimización ordinal restringida permite explorar

espacios de soluciones que contienen planes factibles con una alta

probabilidad y el proceso meta-heurístico permite explorar espacios cercanos

a las soluciones Elite-Pareto para escapar de óptimos locales bajo criterios

sustentables.

c) Fase III (a): La consideración de diversos agentes en la coordinación para

llevar a cabo un plan de expansión genera una mayor complejidad, no solo

determinar donde y cuando se requieren los activos de transmisión, sino

también la valoración de estos.

d) Fase III (b): El costo óptimo de un proyecto está condicionado por la

efectividad en la negociación que lleva a cabo un inversionista con terceros.

Los resultados muestran que determinar cuáles son las características de cada

inversionista, el poder inferir cual es el nivel de esfuerzo y la capacidad de

disminuir los costos permite asignar de forma eficiente los proyectos a los

inversionistas denominados "ideales".

e) Fase III (c): Para la valorar el esfuerzo de cada posible inversionista se utiliza

el modelo de principal-agente y de esta forma se infiere el tipo de

inversionista. El modelo propuesto plantea que cada oferente maximiza su

utilidad en función de su tipo, la racionalidad individual y la compatibilidad

de incentivos.

f) Fase III (d): Se identifica cómo el nivel de competencia, el incentivo de

reconocimiento de costo y el riesgo que determina cada inversionista influyen

en el desarrollo del plan de expansión. Un aspecto relevante a considerar es

13

que si bien pueden participar inversionistas "ideales" en el proceso de

asignación de un proyecto, sus propias restricciones ( rentabilidad,

presupuesto, flujo de caja, entre otras) conlleva a que su participación en las

licitaciones sea restringida. Es decir, se puedan presentar ofertas no-óptimas

en aquellos proyectos que no participen los inversionistas "ideales". Lo

anterior brinda elementos de juicio para re-diseñar el proceso de asignación de

los proyectos.

g) Fase IV (a): El modelo del juego de la transmisión establece el valor óptimo

de un proyecto. El modelo considera costos ocultos y costos de negociación

por servidumbre para obtener una valoración más acertada y evitar retrasos en

la ejecución del proyecto. Un aspecto a destacar es que la metodología puede

evaluar un plan de expansión producto de la optimización meta-heurística o

evaluar un plan de expansión pre-definido por un planificador centralizado.

h) Fase IV (b): el aporte de la investigación se enfoca en identificar las

anomalías mercado/regulación (mecanismos ineficientes), el impacto de los

incentivos implementados para la inversión y asignación de la transmisión, la

implementación de un mecanismo de expansión en función del beneficio de

los agentes, la caracterización de los conflictos entre los agentes de interés en

la expansión y la efectividad de la cooperación (qué expandir y cómo decidir)

mediante un mecanismo no-cooperativo.

1.7 Publicaciones

A continuación, se listan las publicaciones elaboradas en el marco de la

investigación doctoral.

Artículos de revista:

1. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick. “Transmission of electric energy”: A

bibliographic review. IEEE Latin America Transactions, 8, 3, 245-258.

(Anexo A).

14

2. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick, "Multi-objective Transmission Expansion

Planning: Linking Energy Planning Goals and Ordinal Meta-heuristic

Optimization", summit to IEEE Transactions on Power Systems. (Anexo

B).

3. J. D. Molina, J. Contreras and H. Rudnick, "A Principal-Agent Approach

to Transmission Expansion - Part I: Regulatory Framework", IEEE

Transactions on Power Systems, (),-. doi: 10.1109/TPWRS.2012.2201179.

(Anexo C).

4. J. D. Molina, J. Contreras and H. Rudnick, "A Principal-Agent Approach

to Transmission Expansion - Part II: Case Studies", IEEE Transactions on

Power Systems, (),-. doi: 10.1109/TPWRS.2012.2201180. (Anexo D).

5. J. D. Molina, J. Contreras and H. Rudnick, "A Risk-Constrained Project

Portfolio in Transmission Investment", summit to IEEE Transactions on

Power Systems. (Anexo E).

Congresos:

1. J. D. Molina, V. Martínez and H. Rudnick. “Indicadores de Seguridad

Energética: Aplicación al Sector Energético de Chile”, 2nd Latin American

Meeting on Energy Economics, ISSBN 978-956-14-1043-5, Chile, 22-24

mar, 2009.

2. J. D. Molina, V. Martinez, and H. Rudnick, "Technological impact of non-

conventional renewable energy in the Chilean electricity system" in Proc.

of Industrial Technology (ICIT), IEEE International Conference on,

Valparaiso, 14-17 Mar, 2010.

3. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick. "Transmission expansion investment:

Cooperative or non-cooperative game?", in Proc. Power and Energy Society

General Meeting (PES), International Conference on, 25-29 Jul, 2010.

4. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick. "Renewable energy integration: Mechanism

for investment on bulk power transmission", in Proc. Power System

Technology (POWERCON), International Conference on, 24-28 Oct, 2010.

15

5. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick. “Mechanisms and Incentives for

Transmission Expansion: an International Overview”. Transmission &

Distribution Conference & Exposition: Latin America (T&D

Latinamerican), 2010 International Conference on, Sao Paulo, Brasil, 7-10

Nov. 2010.

6. J. D. Molina, V. Martínez y H. Rudnick. Evaluación de escenarios de

generación, diversidad energética y emisiones de CO2 del Sistema

Interconectado Central de Chile. Third ELAEE: Latin American Meeting

on Energy Economics, “Energy, Climate Change and Sustainable

Development- The Challenges for Latin America”, Buenos Aires-

Argentina. 18-19 Abr, 2011.

7. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick, "Transmission Expansion Plan: Ordinal and

Metaheuristic Multiobjective Optimization", in Proc. of Power Tech,

Trondheim, Norway, 19-23 Jun, 2011.

8. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick, “Expansión de la red para la integración de

ERNC: ¿Oportunidades para América Latina?" IX CLAGTEE, Mar del

Plata, Argentina, 6-10 Nov, 2011.

9. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick. "Approaches to transmission planning: a

transmission expansion game", in Proc. Power and Energy Society General

Meeting (PES), International Conference on, San Diego, USA, 22-26 Jul,

2012 (Anexo F).

10. J. D. Molina and H. Rudnick, “Investment in Renewable Transmission

Asset: ¿Who Pays in Chilean System?”, Transmission & Distribution

Conference & Exposition: Latin America (T&D Latinamerican), 2012

International Conference on, Montevideo, Uruguay, 3-6 Sep. 2012.

16

1.8 Organización de la tesis

La tesis se ha organizado en 5 capítulos y 5 anexos. El objetivo de cada capítulo es

presentar los elementos más representativos de cada fase de la investigación y en

los anexos se desarrollan los aspectos matemáticos y de referenciamiento que

sustentan los conceptos descritos en los capítulos. En este primer capítulo, se

plantea la problemática de la expansión de la transmisión, se proponen los

objetivos de investigación y se formula una hipótesis de trabajo. A su vez, se

desarrolla un estado del arte que describe los diferentes modelos y/o técnicas

utilizadas para planificar la expansión de la transmisión. Con base en lo anterior,

se propone una metodología de estudio, se presentan los resultados encontrados y

se lista la productividad científica.

En el capítulo 2, se hace un análisis de la planificación de la expansión de la

transmisión. Se describen los tipos de modelos de planificación en el contexto del

tomador de decisión respecto a un plan de expansión y se describen los diferentes

tipos de incentivos utilizados para la inversión en la transmisión. Luego, se

describen los desafíos que enfrenta la transmisión. Se describen los elementos que

debe contener una buena práctica en la planificación, las anomalías que se han

identificado en diversos modelos, la no existencia de una metodología óptima

(única) de planificación y las experiencias más representativas en las temáticas de

flujo variable, asignación de costo e integración de energías renovables.

En el capítulo 3, se propone la metodología para establecer qué expandir y cómo

decidir la expansión de la transmisión. Se propone un juego en el que interactúan

los agentes de interés en la expansión. Se determinan planes de expansión bajo

criterios de optimalidad económica, seguridad y sustentabilidad. Se valora el plan

de expansión sujeto al costo, oferta y riesgo esperado de los inversionistas y se

evalúa la factibilidad del plan de expansión considerando el método de asignación

de costo y la aceptabilidad de los proyectos.

17

En el capítulo 4, se implementan dos casos de estudio. En el primero, se generan y

analizan diversos planes de expansión y, en el segundo, se evalúa un plan de

expansión pre-definido del Sistema Interconectado Central de Chile (SIC).

Finalmente, en el capítulo 5, se presentan las conclusiones y trabajos futuros. Cabe

resaltar que en los Anexos A-F se encuentran los artículos publicados que soportan

la investigación doctoral.

18

2. EXPANSIÓN DE LA TRANSMISIÓN

La transmisión de energía eléctrica es esencial para el funcionamiento del mercado de

energía. Esta debe desarrollarse como un actor pasivo frente a todos los agentes del

mercado, permitiendo el intercambio de energía en condiciones de máxima confiabilidad

técnica y económica. Al igual que en el sector generación, la transmisión ha presentado

cambios estructurales para generar incentivos para su óptima expansión y una mínima

distorsión de las señales de mercado. A continuación, se presentan los mecanismos e

incentivos desarrollados en la transmisión, los desafíos que enfrentan la expansión de la

transmisión y algunas experiencias de los mercados más representativos.

2.1 Modelos para la planificación de la expansión

En el sistema de transmisión se han establecido dos modelos o enfoques para la

toma de decisiones en el proceso de la expansión. El primero, con un objetivo

centralizado, en el cual el estado o instituciones pertenecientes a la estructura del

estado asumen el rol de planificador global del sistema. El segundo, un modelo

descentralizado, donde instituciones (no necesariamente del estado) evalúan de

manera coordinada o no las expansiones sugeridas por los agentes del mercado.

2.1.1. Modelo centralizado

El modelo centralizado tiene como agente único al estado. Este modelo

predominaba antes de las diversas restructuraciones a nivel mundial y presentaba

menores costos de transacción por integrar la cadena generar-transportar o la

coordinación en la planificación de los sectores de generación y transmisión (las

experiencias internacionales muestran que la planificación de la generación tiene

un rol indicativo para un entorno competitivo con incertidumbre). Se destaca que a

raíz de la segmentación del sector eléctrico, el modelo evolucionaría al modelo

descentralizado. Sin embargo, dicha evolución estaría ligada al tipo de

segmentación y de quienes serían finalmente los propietarios de la red. Es así

19

como se diseñaron empresas del estado que asumieran el rol de generación y

transmisión, respectivamente, donde el transportador era el responsable de la

expansión del sistema de transmisión. A su vez, este transportador mantenía

funciones de operador del mercado. Posteriormente, se crearon instituciones del

estado que realizaban funciones de planificación, pero bajo la coordinación del

transportador y/o el operador del sistema (existen estructuras en el que de forma

legal o contable las propietarios y operadores de la red son diferentes).

El modelo centralizado es el más utilizado en los mercados latinoamericanos

(Rudnick, Araneda & Mocarquer, 2009) . Existe una institución dependiente del

estado, normalmente dependiente del ministerio de energía, que realiza las

funciones de planificación de la red. Los resultados de la planificación se someten

a evaluación pública de los agentes del mercado. En Latinoamérica el modelo de

planificación de Argentina asigna la toma de decisión a la demanda, pero, en

general en los países latinoamericanos se realiza un proceso consultivo donde la

decisión respecto a los proyectos la toma el ente planificador). Dependiendo del

país, el proceso de planificación, se realiza de manera anual o cuatrienal y

normalmente se planifica para un horizonte de estudio de 10 a 15 años.

Finalmente, la institución aprueba las expansiones del sistema de transmisión y

utiliza mecanismos de subastas, tipo licitación, para la asignación de la

construcción y operación de la infraestructura. Además, esta institución evalúa y

aprueba solicitudes de terceros que hagan parte del sistema de transmisión y define

un marco normativo para que terceros cumplan los requerimientos técnicos de

conexión al sistema de transmisión.

2.1.2. Modelo descentralizado

El objetivo principal del modelo descentralizado es dejar en manos de los agentes

privados del mercado la responsabilidad de la expansión del sistema de

transmisión. Normalmente, el estado o instituciones pertenecientes al estado

desarrollan procesos de planificación indicativa. Se realizan estudios respecto a la

20

ubicación y disponibilidad de recursos energéticos y comportamiento de la

demanda para suministrar información confiable y pública a los agentes del

mercado. La inversión y construcción de nueva infraestructura se realiza en

función de los beneficios individuales de los participantes.

Inicialmente, la coordinación para las inversiones era poca o nula en este modelo y

respondía a variables estratégicas del negocio del agente (generador, distribuidor o

clientes no regulados). Básicamente, eliminar las restricciones que se presentaban

en la red relevante para el agente y que afectara sus intereses en el mercado. Esto

trajo consigo que la red no se expandiera de forma óptima y se crearon zonas con

altos niveles de congestión y baja confiabilidad. Por tanto, una evolución del

modelo descentralizado fue la creación de instituciones (no necesariamente del

estado) que agruparan a los agentes relevantes en función del tipo de mercado. La

función principal de esta institución es implementar procesos de planeación

integrada y/o coordinar los proyectos de expansión.

Han sido diversas las configuraciones de las instituciones coordinadoras, en la que

principalmente se consideran las siguientes: institución integrada por los agentes

más relevantes del mercado (grandes generadores, grandes clientes y

transportadores), institución integrada por el transportador y/o operador del

sistema o integradas por diversos transportadores, por ejemplo, el caso Europeo

creó la red europea de operadores del sistema de transmisión de electricidad -

ENTSO-.

En la última década, se incrementó la supervisión de los entes reguladores y la

implementación de incentivos que aumenten la eficiencia y garanticen una mayor

satisfacción técnico-económica de los usuarios. Además, el crecimiento de la

demanda y por ende la del sistema estimula la integración de regiones o países.

Estas interconexiones técnicas conllevan a asignarle a una sola entidad la

responsabilidad de planificación. Finalmente, el modelo descentralizado requiere

que el proceso de planificación sea abierto, transparente y con mecanismos de

participación para todos los usuarios de la red y/o potenciales inversionistas.

21

2.2. Incentivos para la inversión

De acuerdo a lo descrito en el subcapítulo anterior podemos definir dos tipos de

incentivos para el desarrollo de la expansión de la transmisión. El primero, un

incentivo desarrollado por el ente regulador donde este define quién, cómo, dónde

y cuándo se lleva a cabo la expansión sujeta a una metodología de remuneración

(precio techo, con base en el rendimiento, entre otros). El segundo, un incentivo

creado por las fuerzas del mercado en el que se define quién, cómo, dónde y

cuándo (derechos de transmisión, capacidad disponible de transferencia, entre

otros). Adicionalmente, podríamos considerar un tercero, este sería un hibrido

entre los incentivos regulatorios y de mercado (Rosellón, 2003).

2.2.1. Incentivos regulatorios

Dada la presencia de significativas economías de escala, la transmisión se ha

constituido en una actividad monopólica. Por lo que un sistema de remuneración

que busque reconocer su costo de capital y operación, unido a la consideración de

libre acceso para sus usuarios, garantizará condiciones de eficiencia para todo el

sistema. De esta manera, se consideran dos tipos de mecanismos marco para

incentivar la expansión. El primero con base en la eficiencia o mejoramiento de la

red y la asignación de una mayor tasa de retorno de los proyectos de expansión.

Incentivos con base en la eficiencia se orientan a que el regulador interfiera lo

menos posible en el desarrollo de la transmisión. Se establece que los

transportadores tendrían una mayor libertad para llevar a cabo las expansiones

necesarias con el fin de cumplir métricas o indicadores cuantificables o no

manipulados por estos. Normalmente, los indicadores más utilizados son la

reducción de la congestión y el aumento de los flujos de potencia entre líneas de

transmisión que permitan una mayor seguridad y diversidad del suministro del

recurso energético

El reconocimiento de una mayor tasa de retorno fomenta el desarrollo de

inversiones estratégicas para el sistema de transmisión. De esta manera, los

22

transportadores puedan beneficiarse del incremento del rendimiento de capital

asociado a la inversión. Se establece que el incremento de dicha tasa se justifica

por el mayor beneficio que percibirían los agentes del sistema, comúnmente los

consumidores. Sin embargo, un aspecto a evaluar sobre este tipo de incentivo, es

que podría sobredimensionarse para que el transportador lleve a cabo la inversión.

Por lo que se hace necesario definir tasas escalables en función de la utilidad que

entregue cada activo de transmisión.

2.2.2. Incentivos de mercado

Los mecanismos de mercado generan una mayor complejidad, básicamente por el

incremento de agentes con intereses individuales, entes reguladores y

coordinadores que trascienden y separan la propiedad y el control de los activos de

transmisión. Aún más, el acceso no discriminatorio al mercado, la congestión, el

poder de mercado, el acoplamiento de incentivos de corto y largo plazo influyen

en la planeación y operación confiable de la transmisión y en el desarrollo de

reglamentos o normativas acorde para cada agente. Aunque, por otro lado, el

incremento de los agentes participantes de la expansión genera una mayor

competencia y por ende se desarrollan aquellas infraestructuras que entreguen un

mayor beneficio.

El incentivo con base en el mercado se asocia a la competencia que puede

generarse acerca de la adjudicación de los derechos de transmisión. Comúnmente,

se define un valor de capacidad a adjudicar, precios de referencia y los ingresos

adicionales que se recibirían por la expansión de la capacidad y la acción del

mercado. De este modo, el inversionista recibiría las rentas por la capacidad

adicional y se fomenta al transportador a identificar las expansiones necesarias y

bajo un escenario base someterlas al mercado.

Uno de los problemas que surgen es la definición de la capacidad de referencia que

será asignada al mecanismo de mercado. En sistemas con generación dispersa y

alejada del consumo, los agentes interesados en el aumento de la capacidad

23

disminuirían. De tal forma que el propietario de la expansión requeriría que la

capacidad de referencia, inferior a la eficiente, remunere en su totalidad los costos

de la transmisión. Además, comúnmente estos mecanismos se soportan en

sistemas con congestión para que sea factible. La dinámica e incertidumbre que

surgen alrededor de mecanismos financieros (cobertura) y que intrínsecamente

requieran un “mínimo” de congestión para lograr la viabilidad de este mecanismo.

2.2.3. Incentivos híbridos

A nivel mundial, se han implementado tanto incentivos regulatorios como de

mercado. Primordialmente, en los mercados norteamericanos se optaron incentivos

con base en el mercado y en los países europeos con base en incentivos

regulatorios. Las diferentes experiencias internacionales muestran que los modelos

con base en regulación no generan los suficientes incentivos para su expansión y

los de mercado no remuneran en su totalidad los costos de la transmisión. Por

tanto, se diseñan incentivos híbridos para obtener una mayor eficiencia y beneficio

social. Por ejemplo, países como Australia desarrollaron incentivos según las

necesidad especiales del mercado. Además, las características técnicas de la red

(loop flows) hacen que la expansión influya de manera negativa sobre la capacidad

de la red existente. Se propone que los incentivos regulatorios provean inversiones

de largo plazo y los incentivos de mercado desarrollen incrementalmente la

expansión de baja capacidad de redes predominantemente malladas. De esta

manera, los inversionistas de la red reciban los incentivos eficientes para el

desarrollo de la red. Finalmente, podemos destacar al menos dos aspectos que han

impulsado el desarrollo de incentivos híbridos. El primero, la crisis de tipo

financiero o técnico (cuellos de botella y black-outs) del sector eléctrico, tanto de

mercados restructurados o no, y la evolución tecnológica tanto a nivel de

generación como del sistema de transmisión.

24

2.3. Desafíos en la expansión

Las experiencias internacionales muestran que los sistemas de transmisión

presentan características técnicas que no reflejan las transacciones económicas.

Entre ellas las asociadas al flujo de potencia que se constituyen como una barrera

significativa para la formación de mercados eficientes (externalidad tecnológica) y

la posibilidad de comportamientos oportunistas por parte de los agentes,

particularmente, los generadores para manipular el mercado. A continuación, se

realiza un análisis respecto a cuales han sido las mejores experiencias, las

anomalías y si es posible determinar el mejor mecanismo e incentivo.

2.3.1. Buenas prácticas

A nivel de país, podemos mencionar que inicialmente los modelos implementados

en Argentina y Australia se desarrollaron bajo los objetivos propuestos y con

señales positivas para la expansión de la transmisión. El principal aspecto que

caracteriza el modelo australiano es el diseño integrado de corredores para la

expansión, en este participan transportadores y un grupo consultor -ERGIG-

(instituciones del estado). Para el caso Argentina, se utiliza un proceso

participativo para definir la expansión (votación). Sin embargo, en el caso

Argentino, los propietarios de los activos de transmisión no tienen la obligación o

los incentivos para expandir y el planificador presenta un comportamiento reactivo

ante el crecimiento del sistema. A su vez, en el modelo de Australia, se

presentaron problemas de remuneración, proyectos HVDC, y en la actualidad se

está implementando una nueva metodología para incentivar la expansión e

interconexión de centrales de energía, principalmente ERNC. Las buenas prácticas

se pueden caracterizar mediante los siguientes aspectos: sobrecostos poco

significativos en la construcción, mecanismos regulatorios diligentes para dar

soluciones a problemas exógenos de la expansión y el uso promedio proyectado de

la expansión para disminuir el riesgo sobre la rentabilidad financiera de esta.

25

2.3.2. Anomalías

Bajo los conceptos de la economía clásica las instituciones reguladores conciben

conceptos de eficiencia y equidad, pero, sin establecer claramente el beneficio

social. Los principios de eficiencia y equidad son incompatibles dado que el

óptimo social difiere del óptimo individual. Lo anterior sugiere implementar

mecanismos para establecer un compromiso entre los objetivos sociales y el de los

transportadores. Las anomalías o incentivos perversos que puedan generarse

dependerán de la metodología utilizada. En un modelo regulado dependen de las

señales eficientes que brinde el regulador para la correcta actualización del valor

de los activos de transmisión, la tasa de retorno (siendo esta fija o calculada

mediante técnicas como el WACC) y los incentivos/multas para la reposición y

mantenimiento de los activos. La tasa de retorno y la vida útil regulatoria toman

gran relevancia debido a la divergencia que pueda existir con la vida técnica de la

infraestructura y los requerimientos de calidad, seguridad y confiabilidad.

Por otra parte, los avances tecnológicos desafían los conceptos tradicionales de

regulación y las denominadas instalaciones esenciales se han constituido como

“cuellos de botella” en servicios de infraestructura. Además, debido a que los

mecanismos creados para realizar la expansión no estimulan eficientemente la

inversión, la expansión de la capacidad en generación y/o crecimiento de la

demanda no se ha acompañado de la expansión de la transmisión. La

incertidumbre que presentan los flujos de potencia (generación/demanda) genera

cambios en la transmisión que no son reconocidos en la regulación. Generalmente,

la regulación no considera las externalidades sujetas a aspectos tecnológicos,

asimetrías de información entre el regulador y los transportadores, el riesgo y

detrimento de las inversiones por la utilización de tecnologías que controlen los

flujos de potencia (líneas HVDC o sistemas de transmisión flexible en corriente

alterna -FACTS-).

26

2.3.3. ¿Existe un óptimo?

Considerando que la separación de las actividades de generación y transmisión ha

sido dominante a nivel mundial. En las recientes décadas, el debate se enfoca en la

configuración sobre la propiedad y operación de los activos de transmisión. Por

tanto, podemos establecer que con el fin de brindar expansiones eficientes en el

sistema, el marco ideal para el diseño de los mecanismos e incentivos debe

enfocarse en: reducir la congestión, dar solución eficiente a los conflictos de

interés, que se remunere en función de la eficiencia del transportador, que se

brinde un acceso no discriminatorio a la red y que se estimulen las

interconexiones. Sin embargo, en la práctica, las diversas acciones realizadas no

dan una respuesta global a los parámetros descritos. Cada país o región desarrolla

los mecanismos e incentivos más apropiados a la realidad de su red y las variables

políticas y sociales. En la Figura 2-1 se identifican las filosofías de expansión

utilizadas en algunos países. Se muestra como el criterio N-1 y los incentivos

regulados son el soporte para la expansión de la transmisión.

Figura 2-1: Filosofías de expansión.

Incentivos

Confiabilidad

Regulada Mercado

N-2

N-1

N-1*

N

N-k

Económica

“Construir todo lo necesario”

“costo de falla corto plazo”

Robusta

2004

Post‐ 2004

Reino Unido

AlemaniaEEUU (NERC *)

India

Australia (NECA)Nueva Zelanda

Brasil

Australia (occidental)

Francia

Chile

27

En la última década, si bien se han desarrollado incentivos de mercado, los

incentivos regulatorios han tomado una mayor fuerza, básicamente para que el

sector eléctrico se desarrolle bajo las fuerzas del mercado pero con la

implementación de mecanismos regulatorios que disminuyan o elimine las fallas

de este. La tendencia a nivel mundial de los incentivos regulatorios se concentra en

la reducción de costos, mejoramiento de la calidad del servicio, estimulo a la

inversión y precios eficientes de acceso a la red. Adicionalmente, debido a los

diversos “Black-out” ocurridos a nivel mundial se han revaluado los conceptos de

regulación económica y la incidencia de la confiabilidad para la inversión en

transmisión, así como, la consideración de operadores independientes y/o

regionales de la transmisión. En Suramérica, por ejemplo, países como Brasil,

Chile y Colombia desarrollaron metodologías de ingreso regulado y mecanismos

de subastas para la expansión de la red. Argentina implementó mecanismos de

foros para la expansión de la red. Australia, estableció un híbrido entre ingreso

regulado y mecanismo con base en el mercado para proyectos especiales. En

Norteamérica, los mecanismos se enfocaron en la eficiencia de precios (Order 890)

y el desarrollo de mecanismos de mercado para la inversión y manejo de la

congestión. En Europa, se implementaron mecanismos regulatorios para el manejo

de la congestión entre regiones y la creación de un operador regional del sistema

de transmisión -ENTSO-, aunque, también fue posible desarrollar líneas con

propósitos de mercado, principalmente orientados a la interconexión de regiones.

Las experiencias son diversas y varían en función del grado de configuración,

propiedad, tarificación y procesos de planificación de la transmisión (actores

principales). Cada vez más se implementan incentivos híbridos y los nuevos

avances regulatorios se enfocan en el desarrollo de la red de transmisión dedicada

u orientada a las energías renovables. Al igual, que enlaces HVDC en el contexto

de mercado para interconectar países y operadores.

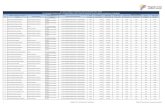

En la Tabla 2-1 se describen las características de los países más representativos.

Se establece el tipo de modelo: Centralizado (C) o Descentralizado (D). Los tipos

28

de incentivos: Regulado (R), Mercado (M) o Híbridos (H). La propiedad de los

activos de transmisión: Privada (P), Estado (S), Mixto (M) o una entidad del

estado (EE). El tipo de modelo de mercado para la actividad de la transmisión:

Operador Independiente del Sistema (ISO), Operador regional de la transmisión

(RTO), Propietarios independiente de los activos de transmisión (ITO) u Operador

y propietario independiente de los activos de transmisión (ITSO) u Operador y

propietario legalmente separados (LTSO). Los agentes que intervienen de forma

directa en el proceso de planificación: agentes o inversionistas (A) y entidades del

estado (EE). Finalmente, se describe si desde el punto de vista normativo existe un

marco regulatorio para fomentar la integración de energías renovables y la

expansión de líneas HVDC con propósito de mercado. Por último, los conflictos

de interés que se presentan entre los generadores, consumidores y propietarios de

la red impactan directamente la expansión eficiente de la transmisión.

29

Tabla 2-1: Comparación de modelos de transmisión