Soberanía y Seguridad Alimentaria ¿Que sabemos?

-

Upload

infoandina-condesan -

Category

Documents

-

view

670 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Soberanía y Seguridad Alimentaria ¿Que sabemos?

La agricultura familiar (ecológica) frente a los retos de la

inseguridad alimentaria en el Perú

Roberto Ugás Programa de Hortalizas, UNALM

Desarrollo Sostenible de Montañas:

Construyendo el futuro que necesitamos Taller regional Post-‐Río+20 Lima, noviembre de 2012

Desnutrición en el mundo (% de población total) 2010-2012 FAO, 2012

Indice de riesgo de seguridad alimentaria 2011 Maplecroft, 2012

FAO, 2012

FAO, SOFI 2012

Chapter 3 ! Extent of food losses and waste 5

Figure 2 shows that the per capita food loss in Europe and North-America is 280-300 kg/year. In Sub-Saharan Africa and South/Southeast Asia it is 120-170 kg/year. The total per capita production of edible parts of food for human consumption is, in Europe and North-America, about 900 kg/year and, in sub-Saharan Africa and South/Southeast Asia, 460 kg/year.

Per capita food wasted by consumers in Europe and North-America is 95-115 kg/year, while this figure in sub-Saharan Africa and South/Southeast Asia is only 6-11 kg/year.

Food losses in industrialized countries are as high as in developing countries, but in developing countries more than 40% of the food losses occur at post harvest and processing levels, while in industrialized countries, more than 40% of the food losses occur at retail and consumer levels. Food waste at consumer level in industrialized countries (222 million ton) is almost as high as the total net food production in sub-Saharan Africa (230 million ton).

The graphs of the seven commodity groups below show the percentage food losses and waste of the edible parts of food products that were produced for human consumption.

In the case of cereals (Figure 3), wheat is the dominant crop supply in medium- and high-income countries, and the consumer phase is the stage with largest losses, between 40-50% of total cereal food waste.

In low-income regions rice is the dominant crop, especially in the highly populated region of South and Southeast Asia. For these regions, agricultural production and postharvest handling and storage are stages in the FSC with relatively high food losses, as opposed to the distribution and consumption levels.

In the roots and tubers group (Figure 4), potato (sweet potato in China) is the dominating crop supply in medium- and high-income countries. Results indicate that all three medium- and high-income regions loose the largest volumes during agricultural production. This mainly depends on postharvest crop grading, due to quality standards set by retailers. Food waste at the consumer level is, however, also high.

Figure 2. Per capita food losses and waste, at consumption and pre-consumptions stages, in different regions

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Europe NorthAmerica &Oceania

IndustrializedAsia

SubsaharaAfrica

Per capita food losses and waste (kg/year)

North Africa,West &

Central Asia

South &Southeast

Asia

Latin America

consumer

production to retailing

FAO, 2011

Fuente: La República

Fuente: InsPtuto Peruano de Economía

MIMDES, 2011

Primera infancia 37

Gráficos 13a, 13b y 13c

Desnutrición crónica en los niños y niñas menores de 5 añosEn porcenta je

Nota: No está disponible e l reporte de las tasas de desnutric ión crónica por quint iles de ingreso para e l año 2 0 0 0.

Fuente: Consulta directa a: < http://w w w 1. ine i.gob.pe/BiblioINEIPub/BancoPub/Est/Lib0 8 1 6/index.htm > , abril, 2 0 0 9.

Fuente: UNICEF, 2011

Inversión en la infancia, 2012

El Comercio, 20 marzo 2011

Fuente: Gonzáles, 2012

Definition of Organic Agriculture1

Organic agriculture is a production system that

sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and

people. It relies on ecological processes,

biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions,

rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects.

Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation

and science to benefit the shared environment and

promote fair relationships and a good quality of life

for all involved.

Spanish Translation:

La agricultura orgánica2 es un sistema de producción que

mantiene y mejora la salud de los suelos, los

ecosistemas y las personas. Se basa fundamentalmente

en los procesos ecológicos, la biodiversidad y los ciclos

adaptados a las condiciones locales, sin usar insumos

que tengan efectos adversos. La agricultura orgánica

combina tradición, innovación y ciencia para favorecer el

medio ambiente que compartimos y promover relaciones

justas y una buena calidad de vida para todos los que

participan en ella.

!!"#$%$&'$())*+,-.$/0$12-$345&6$7-8-*(9$&''-:/90$;8$<;=8+9(>$31(90$;8$?@8-$A

A$B('$)(9(/*('$+*=C8;D(>$-D+9E=;D($0$/;+9E=;D($'-$D+8';.-*(8$';8E8;:+'#$

Definition of Organic Agriculture1

Organic agriculture is a production system that

sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and

people. It relies on ecological processes,

biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions,

rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects.

Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation

and science to benefit the shared environment and

promote fair relationships and a good quality of life

for all involved.

Spanish Translation:

La agricultura orgánica2 es un sistema de producción que

mantiene y mejora la salud de los suelos, los

ecosistemas y las personas. Se basa fundamentalmente

en los procesos ecológicos, la biodiversidad y los ciclos

adaptados a las condiciones locales, sin usar insumos

que tengan efectos adversos. La agricultura orgánica

combina tradición, innovación y ciencia para favorecer el

medio ambiente que compartimos y promover relaciones

justas y una buena calidad de vida para todos los que

participan en ella.

!!"#$%$&'$())*+,-.$/0$12-$345&6$7-8-*(9$&''-:/90$;8$<;=8+9(>$31(90$;8$?@8-$A

A$B('$)(9(/*('$+*=C8;D(>$-D+9E=;D($0$/;+9E=;D($'-$D+8';.-*(8$';8E8;:+'#$

80 millones de hectáreas de Perra cerPficada orgánica

www.fibl.org

Growth of the organic agricultural land and of wild collection areas 1999-2010

11 15 17 20 26 30 29 30 32 35 37 374 6

21 2023

27 2731 31 31

4143

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Mill

ion

hect

ares

AgricultureWild collection

Source: FiBL-IFOAM-SOEL Surveys 2000-2012,based on data from governments, the private sector and certifiers.

Source: FiBL-IFOAM Survey 2012, based on data from governments, the private sector and certifiers.

Crecimiento del comercio orgánico mundial Market Growth Rates

17.9

25.5

40.2

59.1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

2000 2003 2006 2010

Rev

enue

s (U

S$ b

illio

n)

Presented at: BioFach Congresss 2012, Messezentrum Nürnberg, Germany, Feburary 15, 2012

Sahota, 2012

Los 10 países con el mayor consumo de productos orgánicos per capita

Source: FiBL-AMI Survey 2012, based on data from governments, the private sector and market research companies.

Los 10 primeros países en número de productores orgánicos

Orgánico, sostenible, comercio justo, BPA:

La pequeña agricultura orgánica de exportación es

el sector agrario más regulado por certificaciones

obligatorias y voluntarias

El Comercio, 23 octubre 2012

SEGURIDAD ALIMENTARIA La seguridad alimentaria existe cuando todas las personas Penen, en todo momento, acceso Vsico, social y económico a alimentos suficientes, inocuos y nutriPvos que saPsfacen sus necesidades energéPcas diarias y preferencias alimentarias para llevar una vida acPva y sana. Cumbre Mundial de la Alimentación, 1996 Se enPende por seguridad alimentaria al acceso material y económico a alimentos suficientes, inocuos y nutriPvos para todos los individuos, de manera que puedan ser uPlizados adecuadamente para saPsfacer sus necesidades nutricionales y llevar una vida sana, sin correr riesgos indebidos de perder dicho acceso. Estrategia Nacional de Seguridad Alimentaria – ENSA (D.S. 066-‐2004-‐PCM)

SOBERANÍA ALIMENTARIA Es “el derecho de los pueblos a definir sus propias políPcas y estrategias sustentables de producción, distribución y consumo de alimentos que garanPcen el derecho a la alimentación para toda la población, con base en la pequeña y mediana producción, respetando sus propias culturas y la diversidad de los modos campesinos, pesqueros e indígenas de producción agropecuaria, de comercialización y de gesPón de los espacios rurales, en los cuales la mujer desempeña un papel fundamental”. Foro Mundial de Soberanía Alimentaria, 2001 Es “el acceso de las familias de zonas rurales marginadas a suficientes alimentos saludables y nutriPvos para saPsfacer sus necesidades alimenPcias con el objeto de llevar una vida acPva y sana, preferentemente basado en el aprovechamiento de los recursos locales, sustentado en aspectos ambientales, sociales y económicos, y con cerPdumbre en el Pempo”. Proyecto PESA-‐FAO, México

A/HRC/16/49

2 GE.10-17852

Índice Párrafos Página

I. Introducción ........................................................................................................... 1–4 3

II. Diagnóstico: tres objetivos de los sistemas alimentarios ........................................ 5–11 4

III. Contribución de la agroecología al derecho a la alimentación................................ 12–34 7

A. Disponibilidad: la agroecología aumenta la productividad sobre el terreno... 16–20 8

B. Asequibilidad: la agroecología reduce la pobreza rural.................................. 21–25 11

C. Adecuación: la agroecología contribuye a mejorar la nutrición ..................... 26–27 14

D. Sostenibilidad: la agroecología contribuye a la adaptación al cambio climático ......................................................................................................... 28–31 14

E. Participación de los agricultores: un activo para la difusión de las buenas prácticas.......................................................................................................... 32–34 16

IV. Políticas públicas para la propagación de la agroecología ...................................... 35–42 17

A. Dar prioridad a los bienes públicos ................................................................ 37 19

B. La inversión en conocimientos ....................................................................... 38 19

C. Fortalecimiento de la organización social mediante la construcción conjunta .......................................................................................................... 39–40 20

D. Empoderamiento de la mujer.......................................................................... 41 21

E. Organización de los mercados ........................................................................ 42 22

V. Recomendaciones ................................................................................................... 43–47 23

Asamblea General de las NNUU, diciembre 2010 Informe del Relator Especial sobre el derecho a la

alimentación, Olivier De Schutter

- 13.8 millones de peruanos son vulnerables a la inseguridad alimentaria. - La pequeña agricultura proporciona el 66% (volumen) – 50% (gasto)

de los alimentos que comemos los peruanos - “Se hace necesario hacer visible la situación de la pequeña

agricultura y agilizar una agenda que le permita tener una mayor competitividad en la tarea estratégica de alimentar a los peruanos…”

Fuente: Gonzáles, 2012

32 Perspectivas de la agricultura y del desarrollo rural en las Américas –cepal fao iica– 33Una mirada hacia América Latina y el Caribe

subregional. Comparando el comportamiento del sector agropecuario con el crecimiento de toda la economía, se observa que la recuperación del real de la sub-región Sur fue extraordinaria, de , con respecto al , casi tres puntos porcentuales por encima del sub-regional, debido fundamentalmente a las producciones récord de trigo en Brasil y Argentina y de maíz en Argentina (--, ). Contrariamente, el en las demás sub regiones se mantuvo rezagado, con tasas de crecimiento menores al del resto de la economía.

a . durante el período -, indicativo de que la productividad de algunos países crece a mayor velocidad que en otros (para mayor detalle, ver capítulo de Agricultura).

La hipótesis de convergencia indica que los países con relativo retraso respecto a los países líderes en términos de productividad agrícola estarían en ventaja, porque aprovecharían en mayor medida la difusión del co-nocimiento tecnológico y por lo tanto, crecerían más rápidamente. En las Américas domina un proceso con-trario, de divergencia económica, resultado fundamen-talmente de las diferencias entre países en cuanto a: la base de recursos naturales; el nivel tecnológico (incor-porado en el capital fijo y en el capital de trabajo); el capital humano (en su definición amplia para incluir educación, habilidades, conocimiento y capacidades); y los niveles de inversión en investigación agrícola e infraestructura (Hayami y Ruttan, ; Evenson y Kislev, ; Antle, ; Eldon et al., ; Banco Mundial, ).

Al comparar el crecimiento relativo de la productividad agrícola en la última década con respecto a la década previa, se pueden distinguir al menos cuatro grupos de países. En el primer grupo están los países que man-tienen durante los últimos veinte años crecimientos promedio anuales mayores al . En este grupo están, en orden descendente, según valor de la productividad por trabajador agrícola, los ., Canadá, Argentina, República Dominicana, Brasil, Costa Rica y Canadá. El segundo grupo de países ha dado un salto cuantitativo en productividad: de crecer a tasas anuales menores al , e incluso negativas durante la década de los , a tasas de crecimiento mayores al en la última déca-da. En este grupo están Venezuela, Chile, México, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Colombia y Ecuador; siendo notable la recuperación de los dos últimos países. En el tercer grupo de países, las tasas de crecimiento se mantienen por debajo del en los últimos veinte años, aunque la mayoría mejoraron su desempeño en la última década. Dominica, Granada, Suriname, San Vicente y las Granadinas, Belice y Jamaica forman parte dicho grupo. En el cuarto y último grupo se encuentra

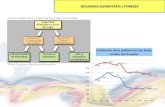

Figura 6. Productividad Agrícola en las Américas, períodos 1990-1999 y 2000-2009(vaa en us$ constantes de 2000 / trabajador agrícola)

Fuente: iica (caespa) con datos del Banco Mundial

Notas: *Caribe incluye solo países con series de datos com-pletos (República Dominicana, Antigua y Barbuda, Belice, Dominica, Granada, Guyana, Haití, Jamaica, San Cristóbal y Nieves, Santa Lucía ,Trinidad y Tobago, San Vicente y las Granadinas); ** No incluye a Canadá por falta de datos en el 2010; *** No incluye a Venezuela por no contar con datos a precios locales desde el 2008

Región 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 1a. PIB (dólares constantes de 2000)Américas 3,18% 2,61% 0,76% -3,16% 3,58%

ALC 5,83% 5,91% 4,29% -1,82% 6,17%

Andina 7,93% 7,65% 5,68% -0,50% 2,95%

Caribe 8,94% 6,02% 3,36% 0,45% 3,71%

Central 6,58% 7,18% 4,28% -0,59% 3,55%

Norte 2,81% 2,03% 0,09% -3,59% 3,14%

Sur 5,22% 6,71% 5,57% -0,26% 7,87% 1b. VAA realAméricas -0,42% -3,12% 5,58% 0,37% 3,65%

ALC 3,99% 4,50% 2,85% -3,89% 6,37%

Andina 3,72% 3,18% 3,12% 0,01% 0,29%

Caribe* 8,12% -1,74% -2,65% 9,62% 3,35%

Central 4,55% 4,93% 1,67% 0,29% 2,07%

Norte** -3,39% -8,61% 7,44% 3,95% 1,22%

Sur 4,13% 5,63% 3,84% -7,21% 10,81% 1c. VAA corriente deflactadoAméricas 1,13% 17,43% 15,67% -11,52% 20,96%

ALC 11,93% 20,65% 20,06% -7,42% 24,53%

Andina*** 9,35% 19,38% 17,29% -1,49% 20,10%

Caribe* 5,49% 2,89% 11,38% -0,22% 9,38%

Central 6,41% 13,54% 10,94% -1,81% 10,95%

Norte** -5,34% 12,60% 9,78% -16,34% 15,90%

Sur 14,26% 28,29% 26,92% -7,59% 30,07%

Cuadro 1: Tasas anuales de crecimiento del pib y del vaa de las Américas (Período 2006-2010)

Fuente: iica (caespa) con datos del Banco Mundial (2012)

El crecimiento positivo del real de en (,) sobresalió frente al de otras regiones del mundo. Fue signi-ficativamente mayor al crecimiento de la Unión Europea (,), de América del Norte (,), del mundo Árabe (,), de los países del Asia del Este y Pacífico (,), y en general, muy superior al crecimiento del agregado mundial, de sólo , (Banco Mundial, ).

Según datos preliminares de la , para se pro-nostica una desaceleración de la agricultura, año en que el real de crecería un aproximadamente, tres veces menos de lo que alcanzó en el . Sin embargo, se presentaron grandes disparidades entre países. Chile experimentó un crecimiento extraordinario de ,, sustentado por el dinamismo del sector de la fruticultura (Banco Central de Chile, ), seguido por Granada, Ecuador y República Dominicana, con crecimientos su-periores al . Perú y Uruguay presentaron crecimientos moderados, entre y , mientras que El Salvador, Tri-nidad y Tobago, Venezuela, Argentina y México bajarían su producción con respecto al .

Los ingresos reales en el sector agrícola experi-mentan grandes oscilaciones anuales

El indicador de corriente deflactado (Cuadro c), permite ver que la crisis golpeó fuertemente al sector en el , reflejando una caída de los ingresos reales de de ,, casi el doble de lo que cayeron los volúmenes de producción (,). Sin embargo, en el , con el re-punte de los precios de commodities agrícolas, los ingresos reales del sector crecieron casi en , incluso por encima del crecimiento experimentado durante el pico de precios del . Ese comportamiento oscilatorio de los ingresos reales de guarda correlación con la evolución de los precios internacionales, que según el índice de alimentos , cayeron , en con respecto a , para luego recuperarse un , en el .

Crecen las brechas en productividad

La productividad agrícola promedio en , medida como el real por trabajador agrícola, promedió . durante la década del -, cifra muy infe-rior a . correspondiente a la productividad pro-medio de Canadá (Figura ). La dispersión entre países de las Américas (calculada como la desviación estándar) aumentó de . constantes en el período -

Destinada a la exportación, en especial, de arándanos, cerezas y uva de mesa.

0 5.000 10.000 15.000 20.000 25.000 30.000 35.000 40.000 45.000

Mundo

Perú

San Cristóbal y Nieves

Honduras

Ecuador

Santa Lucía

Trinidad y Tobago

Paraguay

Nicaragua

El Salvador

Jamaica

San Vincente y Las Granadinas

Colombia

Granada

Guatemala

México

América Latina y el Caribe

Brasil

Surinam

Guyana

República Dominicana

Panamá

Costa Rica

Belice

Chile

Dominica

Venezuela, RB

Uruguay

Argentina

Barbados

Estados Unidos

Canadá

1990-1999 2000-2009

Brecha Entre países

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

1990-1999 2000-2009D

esvi

ació

n Es

tánd

ar

ñ

CEPAL, FAO, IICA, 2012

CEPAL, FAO, IICA, 2012

PNUD-PMA, 2010

Koohafkan et al, 2011

before a threshold is crossed (Rockstrom et al., 2009).This generates a zone of uncertainty around each pro-posed threshold. Undoubtedly, proposed thresholdsmay at first be rough estimates only, surrounded bylarge uncertainties and knowledge gaps. Filling in

these gaps will require major advancements in agroe-cology and resilience science applied at the local levelto capture the specificities of each region.

Thresholds can also be established by examiningwhether the proposed technologies or agricultural

Figure 4 | The basic requirements of a viable and durable agricultural system capable of confronting the challenges of the21st century while carrying out its productive goals within certain thresholds established locally or regionally

Figure 5 | Hypothetical threshold values established for an agricultural community for each type of sovereignty

Green Agriculture 11

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alifo

rnia

, Ber

kele

y] a

t 08:

12 1

7 N

ovem

ber 2

011

Koohafkan et al, 2011

LETTERdoi:10.1038/nature11069

Comparing the yields of organic and conventionalagricultureVerena Seufert1, Navin Ramankutty1 & Jonathan A. Foley2

Numerous reports have emphasized the need for major changes inthe global food system: agriculture must meet the twin challenge offeeding a growing population, with rising demand for meat andhigh-calorie diets, while simultaneously minimizing its globalenvironmental impacts1,2. Organic farming—a system aimed atproducing food with minimal harm to ecosystems, animals orhumans—is often proposed as a solution3,4. However, critics arguethat organic agriculture may have lower yields and would thereforeneed more land to produce the same amount of food as conven-tional farms, resulting in more widespread deforestation and bio-diversity loss, and thus undermining the environmental benefits oforganic practices5. Here we use a comprehensive meta-analysis toexamine the relative yield performance of organic and conven-tional farming systems globally. Our analysis of available datashows that, overall, organic yields are typically lower than conven-tional yields. But these yield differences are highly contextual,depending on system and site characteristics, and range from 5%lower organic yields (rain-fed legumes and perennials on weak-acidic to weak-alkaline soils), 13% lower yields (when best organicpractices are used), to 34% lower yields (when the conventional andorganic systems are most comparable). Under certain conditions—that is, with good management practices, particular crop types andgrowing conditions—organic systems can thus nearly match con-ventional yields, whereas under others it at present cannot. Toestablish organic agriculture as an important tool in sustainablefood production, the factors limiting organic yields need to bemore fully understood, alongside assessments of the many social,environmental and economic benefits of organic farming systems.

Although yields are only part of a range of ecological, social andeconomic benefits delivered by farming systems, it is widely acceptedthat high yields are central to sustainable food security on a finite landbasis1,2. Numerous individual studies have compared the yields oforganic and conventional farms, but few have attempted to synthesizethis information on a global scale. A first study of this kind6 concludedthat organic agriculture matched, or even exceeded, conventionalyields, and could provide sufficient food on current agricultural land.However, this study was contested by a number of authors; thecriticisms included their use of data from crops not truly under organicmanagement and inappropriate yield comparisons7,8.

We performed a comprehensive synthesis of the current scientificliterature on organic-to-conventional yield comparisons using formalmeta-analysis techniques. To address the criticisms of the previousstudy6 we used several selection criteria: (1) we restricted our analysisto studies of ‘truly’ organic systems, defined as those with certifiedorganic management or non-certified organic management, followingthe standards of organic certification bodies (see SupplementaryInformation); (2) we only included studies with comparable spatialand temporal scales for both organic and conventional systems (seeMethods); and (3) we only included studies reporting (or from whichwe could estimate) sample size and error. Conventional systems wereeither high- or low-input commercial systems, or subsistence agriculture.

Sixty-six studies met these criteria, representing 62 study sites, andreporting 316 organic-to-conventional yield comparisons on 34 dif-ferent crop species (Supplementary Table 4).

The average organic-to-conventional yield ratio from our meta-analysis is 0.75 (with a 95% confidence interval of 0.71 to 0.79); thatis, overall, organic yields are 25% lower than conventional (Fig. 1a).This result only changes slightly (to a yield ratio of 0.74) when theanalysis is limited to studies following high scientific quality standards(Fig. 2). When comparing organic and conventional yields it is important

1Department of Geography and Global Environmental and Climate Change Center, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H2T 3A3, Canada. 2Institute on the Environment (IonE), University of Minnesota,1954 Buford Avenue, St Paul, Minnesota 55108, USA.

0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2

Crop typeAll crops (316)

Fruits (14)

Oilseed crops (28)

Cereals (161)

Vegetables (82)

a

0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2

Plant typeLegumes (34)

Non-legumes (282)

Perennials (25)

Annuals (291)

b

0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2Organic:conventional yield ratio

Crop species

Maize (74)

Barley (19)

Wheat (53)

Tomato (35)

Soybean (25)

c

Figure 1 | Influence of different crop types, plant types and species onorganic-to-conventional yield ratios. a–c, Influence of crop type (a), planttype (b) and crop species (c) on organic-to-conventional yield ratios. Only thosecrop types and crop species that were represented by at least ten observationsand two studies are shown. Values are mean effect sizes with 95% confidenceintervals. The number of observations in each class is shown in parentheses. Thedotted line indicates the cumulative effect size across all classes.

0 0 M O N T H 2 0 1 2 | V O L 0 0 0 | N A T U R E | 1

Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved©2012

Seufert et al, 2012

316 comparaciones entre orgánico y convencional en 62 localidades y con

34 cultivos

Los rendimientos orgánicos fueron, en promedio, 75% del

rendimiento convencional

Author's personal copy

The relative yield data were grouped in 10% intervals (Fig. 1).Apart from a few outliers >150%, the relative yields are roughlynormally distributed with a peak for the 70–80% and 80–90% inter-vals. Thirty-six percent of all data had a relative yield between 70%and 90%. Sixty-six percent of all data had a relative yield between60% and 100%.

3.3. Differences between regions, crops, and type of data

The relative yield differs (P < 0.001) across regions of the world;the relative yield was lowest in Northern Europe (70%) and highestin Asia (89%) (Table 2). When analyzing data from the Netherlandsand Denmark, countries with high external input agriculture,which brings actual yields relatively close to the genetic yield po-tential, we found a small but statistically significant difference inthe relative yield for these countries vs. the rest of the data. Undertropical conditions and in developing countries relative yields

tended to be higher when compared to the rest of the data, butthe difference was not statistically significant. Relative yields atindividual commercial farms are significantly higher than thosein trials (88% vs. 81%). Relative yields for on-farm statistics werelower than those from both trials and individual commercial farms.

Differences between crop groups were statistically significant(P = 0.01). Cereals and vegetables have the same relative yield asthe overall average (Table 1). Pulses and fodder crops have slightlyhigher values (88% and 86%, respectively). Root and tuber crops,oilseed crops (both 74%) and fruits (72%) have relative yields lowerthan the average. Testing multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correc-tion) resulted in a statistically significant difference between fruits(72%) and pulses (88%) only. At the individual crop level rice, soy-beans, the category ‘other pulses’, corn, carrots, and grass-clover(in order of decreasing relative yield) perform considerably betterthan the average in terms of relative yields (Table 1). The catego-ries ‘other root and tuber crops’ and ‘other food crops’ also havea high relative yield, but these values are based on only few dataentries. Barley, apple, the category ‘other fodder crops’, flax seed,and strawberries are among the crops that perform considerablybelow average. Some of these have relatively small sample sizes.

3.4. Is the yield gap of organic agriculture positively correlated withthe conventional yield?

Our hypothesis was that the closer conventional agriculturegets to the potential or water-limited yield, the larger the yieldgap between organic and conventional systems will be. For allcrops and the wheat subset the regression line pointed at decreas-ing relative yields as conventional yields increase (Fig. 2). In otherwords, the yield gap between organic and conventional agriculturetended to increase as conventional yields increase. However, thesetrends are only statistically significant for wheat (all data) and soy-beans; for the same crops the mean relative yield associated to then lowest conventional yield entries was significantly higher thanthe mean relative yield associated to the n highest conventionalyield entries (P < 0.001; and P < 0.025 respectively – Table 3). Theexponential component of the regression was non-significant forall crops/subsets.

Fig. 1. Frequency of occurrence of relative yields of organic vs. conventionalagriculture, grouped in 10% intervals.

Table 2Average relative yields of organic practices vs. conventional for different regions and types of data. Averages of regions followed by at least onecommon letter did not differ significantly according to the Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple comparisons corrected with the Bonferroni factor(P < 0.05).

Category of differentiation na Relative yield (%) Remarks

Overall 362 80

Asia 22 89 a Many from India, rest from five other countriesCentral Europe 16 88 ac Switzerland, AustriaMiddle-East & North-Africa 14 85 ac Incl. Turkey (7) and four other countriesNorth-America 126 84 ad USA, CanadaSouthern Europe 34 81 ab European Mediterranean countriesEastern Europe 18 80 ab Post-communist economies, excl. Albania, CroatiaNW-Europe 78 73 bc Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, GBRLatin-America 8 73 ab Vegetables (7), coffee (1)Australia & New Zealand 12 73 bcdNorthern Europe 34 70 b Finland, Sweden, Norway

Netherlands & Denmark vs. rest 50 vs. 312 74 vs. 81 High external input countries. P = 0.019

Developing vs. developed countries 33 vs. 296 84 vs. 79 P = 0.13 (ns)

Tropical vs. non-tropical countries 29 vs. 327 86 vs. 80 P = 0.12 (ns)

Long-term vs. Short-term 66 vs. 249 84 vs. 80 Long = > 5 years. Short = 1–5 years. P = 0.17 (ns)

On-farm vs. trial 42 vs. 226 88 vs. 81 P = 0.038On-farm statistics 59 76

a Categories do not always add up to the total number of entries, as for some data it was uncertain to which category they belong. There mayalso be partial overlap of categories.

T. de Ponti et al. / Agricultural Systems 108 (2012) 1–9 5

De Ponti et al, 2012 Analisis de 362 comparaciones organico-convencional publicadas

The hallmark of a truly sustainable system is its ability to regenerate itself. When it comes to farming, the key to sustainable agriculture is healthy soil, since this is the foundation for present and future growth.

Organic farming is far superior to conventional systems when it comes to building, maintaining and replenishing the health of the soil. For soil health alone, organic agriculture is more sustainable than conventional. When one also considers yields, economic viability, energy usage, and human health, it’s clear that organic farming is sustainable, while current conventional practices are not.

As we face uncertain and extreme weather patterns, growing scarcity and expense of oil, lack of water, and a growing population, we will require farming systems that can adapt, withstand or even mitigate these problems while producing healthy, nourishing food.

After 30 years of side-by-side research in our Farming Systems Trial (FST)®, Rodale Institute has demonstrated that organic farming is better equipped to feed us now and well into the ever changing future.

SUSTAINABLEAs it pertains to farming, this term does not have a standard definition. For the purposes of this paper, we will define sustainable as a system that can maintain or enhance soil fertility indefinitely.

ORGANICMost simply, this refers to a system of farming that does not use synthetic chemicals and, instead, mimics natural systems. This may encompass different farm sizes, practices and philosophies that, at their core, reject the use of toxic, synthetic chemicals.

04

INTRODUCTION Q Organic yields match conventional yields.

Q Organic outperforms conventional in years of drought.

Q Organic farming systems build rather than deplete soil organic matter, making it a more sustainable system.

Q Organic farming uses 45% less energy and is more efficient.

Q Conventional systems produce 40% more greenhouse gases.

Q Organic farming systems are more profitable than conventional.

FST FACTS

COMPARISON OF FST ORGANIC AND CONVENTIONAL SYSTEMS

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

ORGANIC CONVENTIONAL

YIELDS(lbs/a/yr)

PROFIT($/a/yr)

ENERGY INPUT

(MJ/a/yr)

GREENHOUSE GASES

(lbs CO2/a/yr)

4,0

79

$5

58

3,2

64

90

6

4,0

22

$1

90

4,5

68

1,4

00

03

A view of FST

lbs=pounds, a=acre, yr=year, MJ=megajoule

30 años del Rodale’s Farming System Trial (iniciado en 1981)

Tigray, EPopia:

El estudio más grande a nivel mundial mostró que el uso del compost permite incrementar los rendimientos de 2 a 3 veces y que supera a los ferRlizantes químicos en mas del 30% La base de datos incluye información de 974 parcelas de agricultores y de 13 culRvos, tomados entre 2000 y 2006

Principales factores: • compost • abonos verdes y agroforesteria • reducción de la erosión • diversidad de culPvos

Although the cost of production correlates to revenue (e.g., those farms with higher levels of revenue alsohave higher production costs), the overall variance in the cost of production tended to be less than the vari-ance in gross revenue. As such, the certifications with lower costs are not necessarily those with higherincomes. Even though C farms had higher production costs than E farms, C farms still had average net rev-enue of approximately US$757 per hectare, while those of E farms had an average net revenue of approxi-mately only US$528 per hectare. These results must be considered cautiously however in light of not onlythe small sample size, but also the high level of variation in other factors such as average farm size.10

Figure 3.1: Average gross revenue and cost of production

Figure 3.2: Average net income in coffee farms according different certifications

While our pilot studies are not necessarily indicative of systemic trends regarding the economic profitability ofone certification system over another, a general trend of superior net income for certified farms over conven-tional farms is apparent. Although the cost of production associated with most of the certified farms visited weresomewhat higher than conventional production costs, they nevertheless displayed generally higher net incomes.

10 As a general rule, larger farms can be expected to have lower per unit costs. In a separate analysis conducted by the Sustainable CoffeePartnership, the per unit cost for reaching compliance was observed to vary inversely with farm size. In that study, a 0.35 hectarefarm in Uganda was found to have compliance costs approximately 35 times that of a 10 hectare farm in Brazil (Potts & Opitz, 2008).

Conventional

US$/Ha8007005003002000

528

715

757

629

601

E

D

C

B

A

100 400

Conventional

Average cost

Average revenues

2,5002,0001,5001,0005000

1,2771,806

1,3282,043

1,5872,344

1,3561,985

1,3491,950

E

D

C

B

A

US$/Ha

Seeking Sustainability: COSA Preliminary Analysis of Sustainability Initiatives in the Coffee Sector

12

COSA Preliminary Analysis of Sustainability Initiatives in the Coffee Sector, 2008

CompeGGvidad de la pequeña agricultura

AsociaGvidad

Tecnología

Economía de escala

Bajos costos de

producción Calidad

Información de mercados

LogísGca eficiente

Fuente: CEPES, Intermon-‐Oxfam

Basados en los principios de

salud, ecología, jusGcia y cuidado

Intensificación de las

funciones ecológicas

Alimentos para la salud y el bienestar

Empoderamiento de áreas rurales

GaranGzar alimentación y conservar ecosistemas

Fuente: TP Organics-‐agenda de invesPgación para Europa hacia

el 2025

Principios que pueden guiar el diseño y la implementación de proyectos de desarrollo agrícola y rural maximizando su impacto nutricional

1. Dirigir las intervenciones a grupos nutricionalmente vulnerables: hogares rurales mas pobres, mujeres en edad férPl, niños pequeños.

2. Medir la nutrición. 3. Diseñar proyectos que tomen en cuenta las compensaciones nutricionalmente

relevantes en el uso del Gempo de las mujeres. 4. Diseñar estrategias de reducción de la pobreza para beneficiar explícitamente la

nutrición. 5. Promover esquemas producPvos que mejoren el acceso a dietas diversificadas. 6. Mejorar la calidad y el valor de los alimentos producidos. 7. Incorporar comunicación para lograr cambios en el comportamiento para que las

ganancias en producción e ingreso se traduzcan en mejoras nutricionales. 8. No dañar los recursos naturales, parPcularmente el agua. 9. Buscar oportunidades para interactuar con otros programas de desarrollo que

influencian la nutrición.

Fuente: Herforth et al, 2010

MIMDES, 2010

Nuestra hipótesis:

El proyecto AGROECO se propone demostrar -‐ a través de un proceso de invesPgación-‐acción sistémico (agroecología) y de invesPgación por disciplinas cienificas -‐ que la prácPca agroecológica puede contribuir a mejorar efecPvamente las condiciones de seguridad alimentaria, y facilitar mejores oportunidades de desarrollo para las organizaciones de productores campesinos ecológicos y las familias que las componen.

Dimensión de la seguridad alimentaria

Acciones del proyecto AGROECO: InvesGgación-‐acción en:

Disponibilidad Intensificación agroecológica; fomento de la diversidad de culPvos; mejoras en calidad de semilla de papas naPvas; promoción de hortalizas naPvas; invernaderos rúsPcos.

Acceso Acceso a ferias ecológicas locales y regionales; sistema parPcipaPvo de garania; incidencia políPca; derechos de propiedad intelectual.

Uso Etnobotánica; género; nutrición; culinaria campesina; alianza cocinero-‐campesino.

Estabilidad Bancos comunitarios de semillas; mejoras en poscosecha.

InsGtucionalidad Fortalecimiento de organizaciones de productores; incidencia políPca; alianzas.

Seguridad alimentaria

Organizaciones más sólidas

Una mejor relación ciudad-‐campo

Dos procesos en marcha: El 24 de sePembre de 2012 se publicó en El Peruano la Resolución Suprema 306 -‐2012-‐PCM que consPtuye Comisión MulPsectorial para promover la Dieta Andina. La integran 7 Ministerios y APEGA.