Prognostic Impact of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in ...replacement in severe aortic stenosis:...

Transcript of Prognostic Impact of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in ...replacement in severe aortic stenosis:...

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S VO L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

ª 2 0 1 8 B Y T H E AM E R I C A N C O L L E G E O F C A R D I O L O G Y F O UN DA T I O N

P U B L I S H E D B Y E L S E V I E R

Prognostic Impact of Left VentricularEjection Fraction in Patients WithSevere Aortic Stenosis

Tomohiko Taniguchi, MD,a Takeshi Morimoto, MD, MPH,b Hiroki Shiomi, MD,a Kenji Ando, MD,cNorio Kanamori, MD,d Koichiro Murata, MD,e Takeshi Kitai, MD,f Kazushige Kadota, MD,g Chisato Izumi, MD,h

Kenji Nakatsuma, MD,a Tomoki Sasa, MD,i Hirotoshi Watanabe, MD,a Yasuhide Kuwabara, MD,a

Takeru Makiyama, MD,a Koh Ono, MD,a Satoshi Shizuta, MD,a Takao Kato, MD,a Naritatsu Saito, MD,a

Kenji Minatoya, MD,j Takeshi Kimura, MD,a on behalf of the CURRENT AS Registry Investigators

ABSTRACT

ISS

Fro

Cli

Ko

Sh

Jap

Ho

Su

Re

rel

Ma

OBJECTIVES The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic impact of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in

patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS).

BACKGROUND The prognostic impact of LVEF in severe AS remains controversial.

METHODS Among 3,815 consecutive patients with severe AS enrolled in the CURRENT AS (Contemporary Outcomes

After Surgery and Medical Treatment in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis) registry, the present study population

consisted of 3,794 patients after excluding 21 patients without LVEF data. Patients were divided into 4 groups according

to LVEF at index echocardiography (<50%, 50% to 59%, 60% to 69%, and $70%; conservative strategy: n ¼ 388,

n ¼ 390, n ¼ 1,025, and n ¼ 800; initial aortic valve replacement strategy: n ¼ 206, n ¼ 170, n ¼ 375, and n ¼ 440).

Echocardiographic data were site reported, and there was no echocardiography core laboratory.

RESULTS In the conservative group, the cumulative 5-year incidence of the primary outcome measure (a composite of

aortic valve–related death or heart failure hospitalization) was significantly higher in patients with LVEFs <50% and

50% to 59% than in those with LVEFs 60% to 69% and $70% (72.3%, 58.4%, 38.7%, and 35.0%, respectively,

p < 0.001), whereas in the initial aortic valve replacement group, the negative effect of low LVEF was markedly

attenuated (20.2%, 20.3%, 17.7%, and 12.4%, respectively, p ¼ 0.03). After adjusting for confounders, LVEF <50%

(hazard ratio: 1.82; 95% confidence interval: 1.44 to 2.28; p < 0.001) and 50% to 59% (hazard ratio: 1.77; 95% con-

fidence interval: 1.42 to 2.20; p < 0.001) but not 60% to 69% (hazard ratio: 1.14; 95% confidence interval: 0.94 to 1.39;

p ¼ 0.17) were independently associated with poorer outcomes compared with LVEF $70% (reference) in the

conservative group. In the initial aortic valve replacement group, the adjusted risk for the primary outcome measure was

not significantly different across the 4 LVEF groups.

CONCLUSIONS This study demonstrates that survival in patients with severe AS is impaired when LVEF is <60%,

and these findings have implications for decision making with regard to the timing of surgical intervention.

(J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2018;11:145–57) © 2018 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

N 1936-8798/$36.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.036

m the aDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan; bDepartment of

nical Epidemiology, Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan; cDepartment of Cardiology, Kokura Memorial Hospital,

kura, Japan; dDivision of Cardiology, Shimada Municipal Hospital, Shimada, Japan; eDepartment of Cardiology, Shizuoka City

izuoka Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan; fDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe,

an; gDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Kurashiki, Japan; hDepartment of Cardiology, Tenri

spital, Tenri, Japan; iDivision of Cardiology, Kishiwada City Hospital, Kishiwada, Japan; and the jDepartment of Cardiovascular

rgery, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan. This work was supported by an educational grant from the

search Institute for Production Development (Kyoto, Japan). The authors have reported that they have no relationships

evant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

nuscript received July 17, 2017; revised manuscript received August 24, 2017, accepted August 25, 2017.

ABBR EV I A T I ON S

AND ACRONYMS

AS = aortic stenosis

AVA = aortic valve area

AVR = aortic valve

replacement

HF = heart failure

LF = low-flow

LG = low-gradient

LV = left ventricular

LVEF = left ventricular ejection

fraction

PG = pressure gradient

TAVR = transcatheter aortic

valve replacement

Vmax = peak aortic jet velocity

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

146

L ow left ventricular ejection fraction(LVEF) is known to be a potent predic-tor of poorer outcomes in patients

with severe aortic stenosis (AS) (1–4). In thecurrent guidelines for severe AS, systolicfunction is regarded as preserved whenLVEF is $50%, and aortic valve replacement(AVR) is strongly recommended for asymp-tomatic patients with peak aortic jetvelocity (Vmax) $4.0 m/s or mean pressuregradient (PG) $40 mm Hg, if the patient hasan LVEF <50% (Class I, Level of Evidence: Bin the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines;Class I, Level of Evidence: C in the EuropeanSociety of Cardiology guidelines) (5,6).However, this recommendation was based

on previous small, single-center studies thatreported better clinical outcomes with AVR comparedwith conservative management in patients withsevere AS with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction(LVEF <35% or 40%) (7–9), and there has been no pre-vious study supporting the selection of LVEF <50% asthe cutoff value for referral to AVR in asymptomaticpatients. There remains considerable debate as to theimpact of LVEF on clinical outcomes in patients withsevere AS. It is unclear whether LVEF <50% is theappropriate threshold for predicting poor outcomesin conservatively managed patients with severe AS.

SEE PAGE 158

Furthermore, some studies have suggested that LVdysfunction might portend an increased risk forperioperative mortality and affect clinical outcomesafter AVR in patients with severe AS (4,10–12), whereasother studies, including a post hoc analysis of thePARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) ICohort A trial reported that baseline LV dysfunctionwas not associated with 1-year mortality in patientswho underwent surgical AVR or transcatheter AVR(TAVR) (13,14). There is no previous study comparingthe effect of LVEF on long-term outcomes betweenthe conservative and initial AVR strategies.

Therefore, we sought to investigate the impact ofLVEF on clinical outcomes stratified by initial treat-ment strategy (conservative or initial AVR) in a largeJapanese multicenter registry of consecutive patientswith severe AS.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION. The CURRENT AS (Contempo-rary Outcomes After Surgery and Medical Treatmentin Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis) registryis a multicenter, retrospective registry enrolling

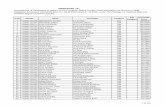

consecutive patients with severe AS among 27 centers(on-site surgical facilities at 20 centers) in Japan be-tween 2003 and 2011 (Online Appendix). The Insti-tutional Review Boards at all participating centersapproved the protocol. The design and patientenrollment of the CURRENT AS registry have beendescribed previously (15). We searched the hospitaldatabase of transthoracic echocardiography andenrolled consecutive patients who met the definitionof severe AS (Vmax >4.0 m/s, mean aortic PG>40 mm Hg, or aortic valve area [AVA] <1.0 cm2) forthe first time during the study period (5,6). Among3,815 study patients in the entire cohort, the presentstudy population included 3,794 patients whoseLVEFs were available at baseline (Figure 1). The studypatients were divided into 4 groups according toLVEF at index echocardiography (<50% in 594patients, 50% to 59% in 560 patients, 60% to 69% in1,400 patients, and $70% in 1,240 patients). Therewere 2,603 patients managed with the conservativestrategy and 1,191 patients managed with the initialAVR strategy, in which AVR was planned on the basisof the findings of index echocardiography (Figure 1).During the study period, TAVR was not approved inJapan and was conducted in the context of the pivotalclinical trial. In the present analysis, the baselinecharacteristics and clinical outcomes were comparedacross the 4 LVEF groups in the entire cohort as wellas in the conservative and initial AVR strata. Thestratified analyses were conducted according to theinitial assignment for the conservative and initialAVR strata regardless of the actual performance ofAVR. Follow-up was commenced on the day of indexechocardiography.

All patients underwent comprehensive 2-dimensionaland Doppler echocardiographic evaluation at eachparticipating center according to the guidelines (16).The biplane Simpson method of disks or the Teich-holz method was used to calculate LVEF. Peak andmean aortic PGs were obtained using the simplifiedBernoulli equation, and AVA was calculated usingthe standard continuity equation and indexed tobody surface area. Echocardiographic data were sitereported, and we had no echocardiography corelaboratory.OUTCOME MEASURES. The primary outcome mea-sure in the present analysis was a composite of aorticvalve–related death or heart failure (HF) hospitaliza-tion. Aortic valve–related death included aortic valveprocedural death, sudden death, and death due toHF possibly related to AS. HF hospitalization wasdefined as hospitalization for worsening HF requiringintravenous drug therapy. Other outcome measuresincluded all-cause death, cardiovascular death,

FIGURE 1 Study Flowchart for the Present Analysis According to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction at Baseline

AS ¼ aortic stenosis; AVR ¼ aortic valve replacement; LVEF ¼ left ventricular ejection fraction.

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

147

sudden death, and noncardiovascular death. Thecauses of death were classified according to the ValveAcademic Research Consortium definitions and wereadjudicated by a clinical event committee (OnlineAppendix) (17,18). Sudden death was defined as un-explained death in patients previously in stable con-dition. Definitions of clinical events are provided inthe Online Appendix.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS. Categorical variables arepresented as numbers and percentages and werecompared using the chi-square test or the Fisherexact test. Continuous variables are expressed asmean � SD or median (interquartile range). Contin-uous variables were compared using 1-way analysisof variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests based on theirdistributions. Cumulative incidence was estimated bythe Kaplan-Meier method, and differences wereassessed using the log-rank test. Consistent with ourprevious report (15), we used 22 clinically relevantfactors, listed in Table 1, as the risk-adjusting vari-ables, and the centers were incorporated as thestratification variable in the multivariate Cox pro-portional hazard models. With the exception of age,the continuous variables were dichotomized by theirmedian values or clinically meaningful referencevalues. The unadjusted and adjusted risks of 3 LVEFgroups (<50%, 50% to 59%, and 60% to 69%) relativeto the LVEF $70% group (reference) for the clinicaloutcome measures were expressed as hazard ratiosand their 95% confidence intervals. In the subgroupanalyses, we assessed the effects of LVEF on

long-term outcomes in patients with high-gradient(Vmax >4.0 m/s or mean aortic PG >40 mm Hg)severe AS and in patients with low-gradient (LG)(Vmax #4.0 m/s, mean aortic PG #40 mm Hg, andAVA <1.0 cm2) severe AS, as well as in asymptomaticand symptomatic patients. We evaluated the inter-action between the subgroup factors and the effectsof LVEF using the multivariate Cox proportionalhazard models. As the sensitivity analyses, we eval-uated the effects of LVEF on long-term clinicaloutcomes in patients without coronary artery disease,in patients without any other valvular disease(moderate or severe), and in patients whose baselineLVEFs were measured using the biplane Simpsonmethod of disks (16). Statistical analyses wereconducted by a physician (T.T.) and a statistician(T. Morimoto) with the use of JMP version 10.0.2(SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) or SAS version9.4 (SAS Institute). All reported p values are 2-tailed,and p values <0.05 were considered to indicatestatistical significance.

RESULTS

BASELINE CLINICAL AND ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC

CHARACTERISTICS. Baseline characteristics weresignificantly different across the 4 LVEF groups inseveral aspects. Patients with LVEFs <50% wereolder, were more often male, and they more often haddiabetes mellitus, prior myocardial infarction, aorticor peripheral vascular disease, renal failure, anemia,

TABLE 1 Baseline Clinical and Echocardiographic Characteristics According to the Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

Categories in the Entire Cohort

LVEF <50%(n ¼ 594)

LVEF 50%–59%(n ¼ 560)

LVEF 60%–69%(n ¼ 1,400)

LVEF $70%(n ¼ 1,240) p Value

Clinical characteristics

Age, yrs* 78.4 � 9.4 78.7 � 10.0 78.0 � 9.7 76.7 � 9.8 <0.001

Age $80 yrs 283 (48) 279 (50) 638 (46) 514 (41) 0.004

Male* 303 (51) 243 (43) 522 (37) 370 (30) <0.001

BMI, kg/m2 21.1 � 3.8 21.5 � 3.8 21.9 � 3.9 22.1 � 3.7 <0.001

BMI <22 kg/m2* 399 (67) 355 (63) 835 (60) 722 (58) 0.001

BSA, m2 1.47 � 0.18 1.45 � 0.19 1.46 � 0.19 1.46 � 0.18 0.58

Hypertension* 421 (71) 379 (68) 1,009 (72) 847 (68) 0.10

Current smoking* 34 (6) 27 (5) 76 (5) 58 (5) 0.73

History of smoking 159 (27) 135 (24) 305 (22) 228 (18) <0.001

Dyslipidemia 191 (32) 164 (29) 469 (34) 498 (40) <0.001

On statin therapy 137 (23) 108 (19) 345 (25) 377 (30) <0.001

Diabetes mellitus 176 (30) 130 (23) 333 (24) 256 (21) <0.001

On insulin therapy* 37 (6) 32 (6) 66 (5) 53 (4) 0.25

Prior myocardial infarction* 140 (24) 63 (11) 74 (5) 42 (3) <0.001

Coronary artery disease* 290 (49) 189 (34) 361 (26) 295 (24) <0.001

Prior PCI 137 (23) 81 (14) 168 (12) 115 (9) <0.001

Prior CABG 67 (11) 40 (7) 50 (4) 40 (3) <0.001

Prior open heart surgery 83 (14) 61 (11) 101 (7) 69 (6) <0.001

Prior symptomatic stroke* 87 (15) 73 (13) 228 (16) 112 (9) <0.001

Atrial fibrillation or flutter* 146 (25) 158 (28) 307 (22) 212 (17) <0.001

Aortic/peripheral vascular disease* 65 (11) 46 (8) 105 (8) 65 (5) <0.001

Serum creatinine, mg/dl* 1.1 (0.8–2.1) 1.0 (0.7–1.5) 0.9 (0.7–1.2) 0.8 (0.7–1.0) <0.001

Creatinine >2 mg/dl 151 (25) 108 (19) 198 (14) 100 (8) <0.001

Hemodialysis* 105 (18) 83 (15) 149 (11) 67 (5) <0.001

Anemia*† 380 (64) 341 (61) 775 (55) 611 (49) <0.001

Liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B/C)* 6 (1) 2 (0.4) 19 (1) 10 (1) 0.19

Malignancy 85 (14) 69 (12) 192 (14) 170 (14) 0.79

Malignancy currently under treatment* 21 (4) 17 (3) 63 (5) 48 (4) 0.45

Chest wall irradiation 6 (1) 3 (1) 9 (1) 7 (1) 0.70

Immunosuppressive therapy 24 (4) 18 (3) 38 (3) 50 (4) 0.23

Chronic lung disease 64 (11) 67 (12) 137 (10) 130 (10) 0.55

Chronic lung disease (moderate or severe)* 23 (4) 18 (3) 37 (3) 33 (3) 0.43

Logistic EuroSCORE, % 19.3 (10.9–31.7) 10.9 (6.2–18.0) 9.0 (5.5–14.4) 7.9 (4.9–12.8) <0.001

EuroSCORE II, % 5.7 (3.4–10.3) 3.1 (1.8–5.6) 2.7 (1.6–4.1) 2.4 (1.3–3.7) <0.001

STS PROM score, % 5.8 (3.3–10.4) 4.6 (2.6–7.9) 3.7 (2.2–6.0) 3.0 (2.0–4.9) <0.001

Symptom related to AS 452 (76) 347 (62) 628 (45) 562 (45) <0.001

Chest pain 70 71 146 204

Syncope 22 38 80 56

Heart failure 431 300 477 384

HF hospitalization at index echocardiography* 280 (47) 168 (30) 195 (14) 141 (11) <0.001

Etiology of aortic stenosis

Degenerative 549 (92) 503 (90) 1,251 (89) 1,057 (85) 0.001

Congenital (unicuspid, bicuspid, or quadricuspid) 30 (5) 34 (6) 79 (6) 114 (9)

Rheumatic 9 (2) 20 (4) 61 (4) 59 (5)

Infective endocarditis 1 (0.2) 2 (0.4) 2 (0.1) 2 (0.2)

Other 5 (1) 1 (0.2) 7 (0.5) 8 (0.7)

Continued on the next page

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

148

and coronary artery disease. Patients withLVEFs <50% also were more often symptomatic atbaseline and had higher surgical mortality risk scores,such as logistic European System for Cardiac Opera-tive Risk Evaluation score, European System for

Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II score, and Soci-ety of Thoracic Surgeons score. With decreasingLVEF, there were incremental decreases in Vmax andAVA and an incremental increase in LV end-diastolicdiameter. Patients with low LVEFs (<50% 50% to

TABLE 1 Continued

LVEF <50%(n ¼ 594)

LVEF 50%–59%(n ¼ 560)

LVEF 60%–69%(n ¼ 1,400)

LVEF $70%(n ¼ 1,240) p Value

Echocardiographic variables

Vmax, m/s 3.78 � 0.99 4.13 � 0.96 4.11 � 0.87 4.33 � 0.86 <0.001

Vmax $5 m/s 81 (14) 99 (18) 245 (18) 268 (22) <0.001

Vmax $4 m/s* 255 (43) 316 (56) 769 (55) 829 (67) <0.001

Peak aortic PG, mm Hg 61 � 31 72 � 34 71 � 30 78 � 31 <0.001

Mean aortic PG, mm Hg 35 � 19 40 � 20 40 � 19 45 � 20 <0.001

AVA (continuity equation), cm2 0.68 � 0.20 0.70 � 0.19 0.73 � 0.17 0.74 � 0.18 <0.001

Indexed AVA, cm2/m2 0.47 � 0.14 0.49 � 0.13 0.51 � 0.13 0.51 � 0.12 <0.001

LV end-diastolic diameter, mm 52.7 � 7.8 46.9 � 6.6 44.5 � 5.8 43.9 � 5.9 <0.001

LV end-systolic diameter, mm 42.3 � 8.2 33.0 � 5.7 28.6 � 4.5 25.1 � 4.4 <0.001

LVEF, % 38.1 � 8.6 55.0 � 2.8 65.0 � 2.8 75.6 � 4.9 <0.001

IVST in diastole, mm 10.9 � 2.4 11.6 � 2.2 11.2 � 2.2 11.6 � 2.3 <0.001

PWT in diastole, mm 10.5 � 2.2 11.1 � 2.2 10.9 � 1.9 11.2 � 2.0 <0.001

Any combined valvular disease (moderate or severe)* 303 (51) 278 (50) 543 (39) 428 (35) <0.001

Moderate or severe AR 135 (23) 138 (25) 277 (20) 239 (19) 0.03

Moderate or severe MS 14 (2) 22 (4) 54 (4) 43 (3) 0.37

Moderate or severe MR 211 (36) 152 (27) 240 (17) 155 (13) <0.001

Moderate or severe TR 127 (21) 101 (18) 223 (16) 175 (14) <0.001

TR PG $40 mm Hg* 142 (24) 105 (19) 176 (13) 181 (15) <0.001

Treatment strategy

Initial AVR 206 (35) 170 (30) 375 (27) 440 (35) <0.001

Conservative 388 (65) 390 (70) 1,025 (73) 800 (65)

Values are mean � SD or n (%). *Potential independent variables selected for the Cox proportional hazard model. †Anemia was defined according to the World HealthOrganization criteria (hemoglobin <12.0 g/dl in women and <13.0 g/dl in men).

AR ¼ aortic regurgitation; AVA ¼ aortic valve area; AVR ¼ aortic valve replacement; BMI ¼ body mass index; BSA ¼ body surface area; CABG ¼ coronary artery bypassgrafting; EuroSCORE ¼ European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; HF ¼ heart failure; IVST ¼ interventricular septal thickness; LV ¼ left ventricular; LVEF ¼ leftventricular ejection fraction; MR ¼ mitral regurgitation; MS ¼ mitral stenosis; PCI ¼ percutaneous coronary intervention; PG ¼ pressure gradient; PROM ¼ Predicted Risk ofMortality; PWT ¼ posterior wall thickness; STS ¼ Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TR ¼ tricuspid regurgitation; Vmax ¼ peak aortic jet velocity.

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

149

59%) more often had other valvular diseases (Table 1).The differences in the baseline characteristics acrossthe 4 LVEF groups in the conservative stratum and inthe initial AVR stratum were consistent with those inthe entire cohort (Online Tables 1 and 2).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES. The median follow-up periodin the entire cohortwas 1,334 days (interquartile range:1,019 to 1,701 days), with a 93% follow-up rate at2 years. During the entire follow-up period, 1,734patients (46%) actually underwent surgical AVR(n ¼ 1,695) or TAVR (n ¼ 39) patients in the entirecohort, with the highest cumulative incidence of sur-gical AVR or TAVR in the LVEF$70% group (Figure 2A).The cumulative 5-year incidence of the primaryoutcome measure (a composite of aortic valve–relateddeath or HF hospitalization) was significantly higher inpatients in the low LVEF groups (<50% and 50% to59%) than in patients in the high LVEF groups (60% to69% and $70%) (Figure 2B, Table 2).

In the conservative stratum, surgical AVR or TAVRwas performed during the entire follow-up period in566 patients (22%), with no significant difference in

the cumulative incidence of surgical AVR or TAVRacross the 4 baseline LVEF groups (Figure 3A). Thecumulative 5-year incidence of the primary outcomemeasure was significantly higher in patients in thelow LVEF groups than in patients in the high LVEFgroups (Figure 4A). After adjusting the confounders,the excess risks of LVEF <50% and LVEF 50% to 59%,respectively, relative to LVEF $70% (reference) forthe primary outcome measure remained highly sig-nificant, whereas the risk of LVEF 60% to 69% rela-tive to LVEF $70% for the primary outcome measurewas not significant (Figure 5). The effect sizes relativeto the reference group were numerically similar be-tween the 2 groups of patients with LVEFs <50% and50% to 59%. There also was a significant excessadjusted risk for sudden death in patients withLVEFs <50% and 50% to 59% relative to those withLVEFs $70% (Figure 5).

In the initial AVR stratum, surgical AVR or TAVRwas actually performed in 1,168 patients (98%). AVRtended to be performed earlier in patients withLVEFs <50% (Figure 3B). The 30-day mortality rateafter AVR in patients with the initial AVR strategy

FIGURE 2 Time-to-Event Curves According to the Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Categories in the Entire Cohort

Cumulative incidences of surgical AVR or TAVR (A) and the primary outcome measure (B). TAVR ¼ transcatheter aortic valve replacement;

other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

150

was not different across the 4 LVEF groups (<50%,2.1%; 50% to 59%, 2.4%; 60% to 69%, 1.9%;and $70%, 1.2%; p ¼ 0.68). The cumulative 5-yearincidence of the primary outcome measure trended

higher in patients in the low LVEF groups than inpatients in the high LVEF groups; however, thenegative effect of low LVEF was markedly attenu-ated in the initial AVR stratum (Figure 4B, Table 2).

TABLE 2 Cumulative Incidences of Events According to the Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Categories in the Conservative and

Initial Aortic Valve Replacement Strata

LVEF <50% LVEF 50%–59% LVEF 60%–69% LVEF $70%

p ValueNumber of Patients With at Least 1 Event (Cumulative 5-yr Incidence)

Conservative stratum (n ¼ 388) (n ¼ 390) (n ¼ 1,025) (n ¼ 800)

Composite of aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization 202 (72.3) 179 (58.4) 303 (38.7) 214 (35.0) <0.001

All-cause death 278 (78.4) 210 (61.1) 446 (48.3) 270 (38.6) <0.001

Cardiovascular death 203 (67.1) 144 (46.5) 280 (33.8) 167 (26.8) <0.001

Aortic valve–related death 143 (55.6) 102 (35.5) 173 (22.5) 117 (20.4) <0.001

Sudden death 40 (18.8) 41 (15.0) 58 (7.9) 29 (4.8) <0.001

Noncardiovascular death 75 (34.3) 66 (27.3) 166 (22.0) 103 (16.1) <0.001

HF hospitalization 151 (64.0) 143 (52.0) 236 (32.7) 173 (29.4) <0.001

Initial AVR stratum (n ¼ 206) (n ¼ 170) (n ¼ 375) (n ¼ 440)

Composite of aortic valve–related death or HF hospitalization 36 (20.2) 31 (20.3) 50 (17.7) 47 (12.4) 0.03

All-cause death 63 (35.7) 36 (23.7) 71 (23.3) 65 (16.5) <0.001

Cardiovascular death 37 (22.6) 24 (15.9) 47 (16.5) 42 (9.9) 0.02

Aortic valve–related death 19 (9.5) 13 (8.0) 20 (6.2) 15 (3.6) 0.01

Sudden death 8 (5.5) 4 (4.5) 10 (3.8) 5 (1.7) 0.12

Noncardiovascular death 26 (16.9) 12 (9.2) 24 (8.2) 23 (7.3) 0.004

HF hospitalization 17 (11.8) 19 (13.9) 32 (12.9) 34 (9.5) 0.49

Values are n (%). The number of patients with at least 1 event was counted throughout the entire follow-up period, whereas the cumulative incidence was truncated at 5 years.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

151

After adjusting the confounders, the risks ofLVEF <50%, 50% to 59%, and 60% to 69%, respec-tively, relative to LVEF $70% for the primaryoutcome measure were no longer significant(Figure 5). The results for the secondary outcomemeasures were fully consistent with those for theprimary outcome measure in both the conservativeand initial AVR strata (Figure 5).

SUBGROUP ANALYSES AND SENSITIVITY ANALYSES. Inthe subgroup analyses (high-gradient AS vs. LG ASand asymptomatic vs. symptomatic), there were nosignificant interactions between the subgroup factorsand the effect of the 4 LVEF groups on the cumulative5-year incidence of the primary outcome measure inboth the conservative stratum (interaction p ¼ 0.46and 0.61, respectively) and initial AVR stratum(interaction p ¼ 0.32 and p ¼ 0.51, respectively)(Online Figures 1 and 2).

The results of the sensitivity analyses in patientswithout coronary artery disease, in patients withoutany other valvular disease, and in patients whoseLVEFs were measured using the biplane Simpsonmethod of disks were fully consistent with the resultsin the entire study population (Online Figures 3 to 5).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the present study were as fol-lows. 1) In the conservatively managed patients with

severe AS, LVEF 50% to 59% and LVEF <50%, but notLVEF 60% to 69%, were independently associatedwith poorer long-term outcomes compared withLVEF $70%. 2) In patients managed with the initialAVR strategy, the negative effect of low LVEF wasmarkedly attenuated without any significant differ-ences across the 4 LVEF groups in the adjusted risksfor the long-term outcomes.

In the current guidelines for severe AS, LV systolicfunction is regarded as preserved when LVEF is $50%(5,6). The American College of Cardiology andAmerican Heart Association guidelines in 1998 and2008 recommended surgical AVR for asymptomaticpatients with severe AS and LV systolic dysfunction,because patients with LV systolic dysfunction werereported to be at especially high risk for all-causedeath without AVR (19,20). However, there arelimited data supporting LVEF <50% as an appropriatecutoff value for LV systolic dysfunction in patientswith severe AS. Pellikka et al. (21) reported that therisk for sustaining cardiac events was higher inasymptomatic patients with LVEFs <50% comparedwith asymptomatic patients with LVEFs $50%.However, that study did not clarify whetherLVEF <50% was the appropriate cutoff value forpredicting worse clinical outcomes in asymptomaticpatients with severe AS. Pereira et al. (8) and Pai et al.(9) reported that survival was better in patients whounderwent surgical AVR during the follow-up periodthan in those managed conservatively among

FIGURE 3 Cumulative Incidence of Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement or Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement According to the

Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Categories

(A) Conservative stratum and (B) initial AVR stratum. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

152

patients with mean aortic PGs #30 mm Hg andLVEFs #35%, and Tribouilloy et al. (7) demonstratedthat surgical AVR was associated with better out-comes compared with conservative management in

symptomatic patients with low-flow (LF) (strokevolume index <35 ml/m2), LG AS and LVEF #40%.These studies are cited in the current AmericanCollege of Cardiology and American Heart Association

FIGURE 4 Cumulative Incidence of the Primary Outcome Measure According to the Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Categories

(A) Conservative stratum and (B) initial AVR stratum. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

153

FIGURE 5 Crude and Adjusted Risks for Clinical Events According to the Baseline Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Categories

(A) Conservative stratum and (B) initial aortic valve replacement (AVR) stratum. CI ¼ confidence interval; HF ¼ heart failure; HR ¼ hazard

ratio; N/A ¼ not assessed.

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

154

guidelines as the references supporting the AVRstrategy in asymptomatic patients with severe AS andreduced LVEFs (<50%) (6). However, patientsincluded in these studies were mostly symptomatic,

and the cutoff value of LVEF for LV systolicdysfunction was not 50% in these studies. In thepresent study, LVEF <50% and 50% to 59%, but notLVEF 60% to 69%, were independently associated

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

155

with poorer outcomes compared with LVEF $70%in the conservative group, despite similar incidencesof AVR among the 4 groups. These findings haveimplications for decision making with regard to thetiming of surgical intervention. Therefore, we shouldrevisit the optimal cutoff value of LVEF for LVsystolic dysfunction in patients with severe AS,in whom LVEF 50% to 59% may not be regardedas “normal.”

LVEF is determined not only by the extent ofmyocardial shortening but also by the relationshipof ventricular wall thickness to ventricular cavitysize (21). LVEF tends to increase in relation to theextent of LV concentric remodeling, which isgenerally observed in patients with severe AS.Furthermore, several studies have reported thatreduced stroke volume despite “normal” LVEF inpatients with severe AS was associated with pooroutcomes (22–24). This paradoxical LF condition wasassociated with smaller LV chamber size, concentricremodeling, diastolic dysfunction, hypertension,and, relatively lower LVEF within the “normal”range (23,25,26). Eleid et al. (27) reported that pa-tients with LF had lower LVEFs compared withthose with normal flow; in the paradoxical LF, LG ASgroup, 37% of patients had LVEFs in the 50% to 59%range, whereas only 16% had LVEFs in the 50% to59% range in the normal-flow, high-gradient ASgroup. Another study including patients with severeAS and LVEF $55% demonstrated that patients withparadoxical LF, LG AS were more likely to haveLVEFs <60% (26). Dahl et al. (12) reported thatstroke volume index was lower in patients withLVEFs 50% to 59% compared with those withLVEFs >60% despite larger LV size, suggesting thatLV systolic function was impaired in patients withLVEFs 50% to 59%. Therefore, the worse outcomesin patients with paradoxical LF, LG AS with LVEFs50% to 59% could be attributed to reduced LVfunction, which has not been adequately studiedbecause LVEF $50% in patients with severe AS hasbeen regarded as “normal.”

The impact of LVEF on long-term clinical outcomesafter surgical AVR or TAVR in patients with severe ASremains controversial (10,12–14,28). A recently re-ported meta-analysis suggested that pre-operativelow LVEF was associated with increased 1-year mor-tality after TAVR compared with preserved LVEF,although no statistical adjustment was performed forbaseline characteristics, despite the fact that thestudies included in the meta-analysis were mostlyobservational studies except for the PARTNER ICohort A trial (28). Dahl et al. (12) reported that LVEF

50% to 59% and LVEF <50% were associated withincreased mortality compared with higher LVEFs inpatients undergoing surgical AVR. In contrast, posthoc analysis of the PARTNER I Cohort A trial and areport from TVT (Transcatheter Valve Therapies)registry with adjustment for baseline characteristicsreported that baseline LV dysfunction was not asso-ciated with worse 1-year mortality in patients whounderwent surgical AVR or TAVR (13,14). The presentstudy clearly demonstrated that the adjusted risks ofthe lower LVEF categories for long-term clinical out-comes were not significant in the initial AVR group.LV systolic dysfunction in many patients with severeAS has been reported to be caused by impairedadaptation to excessive afterload or LV hypertrophy(6,29). Recent studies reported that a rapid and sub-stantial improvement in LVEF after surgical AVR orTAVR was observed in patients with severe AS and LVsystolic dysfunction (13,30,31), which might beamong the reasons why the short- and long-termoutcomes after AVR were similar across the 4 LVEFgroups in the present study. Considering theextremely poor outcomes of patients with severe ASwith LV systolic dysfunction when managed conser-vatively, surgical AVR or TAVR should not be deniedsolely because of the presence of severe LV systolicdysfunction.

STUDY LIMITATIONS. First, echocardiographic datawere site reported, and we had no echocardiographycore laboratory. Therefore, we cannot deny thepossibility of measurement error and variationsin echocardiographic measurements. However,echocardiographic measurements were performedaccording to guidelines by experienced cardiologistsand/or ultrasonographers at each participating center(16).

Second, we included patients whose LVEFs weremeasured using the Teichholz method, which is notrecommended as the method for LVEF measurementin the current guidelines. However, the sensitivityanalysis in patients who had LVEF was calculatedusing the biplane Simpson method of disks was fullyconsistent with the results in the entire studypopulation.

Third, we did not assess the changes in LVEFduring follow-up, because of the retrospective studydesign that did not pre-define the timing of follow-upechocardiographic examinations.

Fourth, we did not collect data on flow and strokevolume index, considering their unreliable nature in aretrospective multicenter study, although they areknown to be strong predictors of outcomes.

PERSPECTIVES

WHAT IS KNOWN? In the current guidelines for

severe AS, systolic function is regarded as preserved

when LVEF is $50%. Evidence to date on the

appropriate threshold LVEF for predicting poorer

outcomes remains conflicting.

WHAT IS NEW? The present study demonstrated

that LVEF 50% to 59% and <50%, but not LVEF 60%

to 69%, were independently associated with poorer

long-term outcomes compared with LVEF $70% with

the conservative strategy. In the initial AVR strategy,

the adjusted risk of low LVEF for the primary outcome

measure (a composite of aortic valve–related death or

HF hospitalization) was markedly attenuated across

the 4 LVEF groups.

WHAT IS NEXT? We should revisit the optimal cutoff

value of LVEF for LV systolic dysfunction in patients

with severe AS.

Taniguchi et al. J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8

Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7

156

Fifth, we could not exclude the effects of unmea-sured confounders, although we performed theextensive adjusted analysis together with the sensi-tivity analyses.

Finally, we did not collect data on dobutaminestress echocardiography, contractile reserve, and LVdiastolic function.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that survival in patients withsevere AS is impaired when LVEF is <60%, and thesefindings have implications for decision making withregard to the timing of surgical intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors thank AyanoIchiyanagi, Akiko Arai, and Hisako Fukazawa forsecretarial assistance.

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE: Dr. TakeshiKimura, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medi-cine, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, 54Shogoin Kawahara-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507,Japan. E-mail: [email protected].

RE F E RENCE S

1. Morris JJ, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, et al.Determinants of survival and recovery of leftventricular function after aortic valve replace-ment. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:22–9.

2. Halkos ME, Chen EP, Sarin EL, et al. Aortic valvereplacement for aortic stenosis in patients withleft ventricular dysfunction. Ann Thorac Surg2009;88:746–51.

3. Mihaljevic T, Nowicki ER, Rajeswaran J, et al.Survival after valve replacement for aortic steno-sis: implications for decision making. J ThoracCardiovasc Surg 2008;135:1270–8.

4. Une D, Mesana L, Chan V, et al. Clinical impactof changes in left ventricular function after aorticvalve replacement: analysis from 3112 patients.Circulation 2015;132:741–7.

5. Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al.Guidelines on the management of valvular heartdisease (version 2012). Eur Heart J 2012;33:2451–96.

6. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014AHA/ACC guideline for the management of pa-tients with valvular heart disease: a report of theAmerican College of Cardiology/American HeartAssociation Task Force on Practice Guidelines.Circulation 2014;129:e521–643.

7. Tribouilloy C, Levy F, Rusinaru D, et al. Outcomeafter aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis without contractilereserve on dobutamine stress echocardiography.J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1865–73.

8. Pereira JJ, Lauer MS, Bashir M, et al. Survivalafter aortic valve replacement for severe aorticstenosis with low transvalvular gradients and

severe left ventricular dysfunction. J Am CollCardiol 2002;39:1356–63.

9. Pai RG, Varadarajan P, Razzouk A. Survivalbenefit of aortic valve replacement in patientswith severe aortic stenosis with low ejectionfraction and low gradient with normal ejectionfraction. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:1781–9.

10. Goldberg JB, DeSimone JP, Kramer RS, et al.Impact of preoperative left ventricular ejectionfraction on long-term survival after aortic valvereplacement for aortic stenosis. Circ CardiovascQual Outcomes 2013;6:35–41.

11. Clavel MA, Berthelot-Richer M, Le Ven F, et al.Impact of classic and paradoxical low flow onsurvival after aortic valve replacement for severeaortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:645–53.

12. Dahl JS, Eleid MF, Michelena HI, et al. Effect ofleft ventricular ejection fraction on postoperativeoutcome in patients with severe aortic stenosisundergoing aortic valve replacement. Circ Car-diovasc Imaging 2015;8:e002917.

13. Elmariah S, Palacios IF, McAndrew T, et al.Outcomes of transcatheter and surgical aorticvalve replacement in high-risk patients with aorticstenosis and left ventricular dysfunction: resultsfrom the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves(PARTNER) trial (Cohort A). Circ Cardiovasc Interv2013;6:604–14.

14. Baron SJ, Arnold SV, Herrmann HC, et al.Impact of ejection fraction and aortic valvegradient on outcomes of transcatheter aortic valvereplacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2349–58.

15. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, et al. Initialsurgical versus conservative strategies in patients

with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J AmColl Cardiol 2015;66:2827–38.

16. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Rec-ommendations for chamber quantification: areport from the American Society of Echo-cardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Commit-tee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group,developed in conjunction with the European As-sociation of Echocardiography, a branch of theEuropean Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echo-cardiogr 2005;18:1440–63.

17. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Stan-dardized endpoint definitions for transcatheteraortic valve implantation clinical trials: a consensusreport from the Valve Academic Research Con-sortium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:253–69.

18. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Genereux P, et al.Updated standardized endpoint definitions fortranscatheter aortic valve implantation: the ValveAcademic Research Consortium-2 consensusdocument. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1438–54.

19. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of pa-tients with valvular heart disease. A report of theAmerican College of Cardiology/American Heart As-sociation. Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Com-mittee on Management of Patients with ValvularHeart Disease). J AmColl Cardiol 1998;32:1486–588.

20. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al.2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management ofpatients with valvular heart disease: a report of theAmerican College of Cardiology/American HeartAssociation Task Force on Practice Guidelines(Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelinesfor the Management of Patients With Valvular

J A C C : C A R D I O V A S C U L A R I N T E R V E N T I O N S V O L . 1 1 , N O . 2 , 2 0 1 8 Taniguchi et al.J A N U A R Y 2 2 , 2 0 1 8 : 1 4 5 – 5 7 Prognostic Impact of LVEF in Severe AS

157

Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardio-vascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascu-lar Angiography and Interventions, and Society ofThoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:e1–142.

21. Pellikka PA, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ.The natural history of adults with asymptomatic,hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. J AmColl Cardiol 1990;15:1012–7.

22. Herrmann HC, Pibarot P, Hueter I, et al. Pre-dictors of mortality and outcomes of therapy inlow-flow severe aortic stenosis: a Placement ofAortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trialanalysis. Circulation 2013;127:2316–26.

23. Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P.Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aorticstenosis despite preserved ejection fraction isassociated with higher afterload and reducedsurvival. Circulation 2007;115:2856–64.

24. Clavel MA, Dumesnil JG, Capoulade R,Mathieu P, Senechal M, Pibarot P. Outcome ofpatients with aortic stenosis, small valve area, andlow-flow, low-gradient despite preserved leftventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol2012;60:1259–67.

25. Clavel MA, Fuchs C, Burwash IG, et al. Pre-dictors of outcomes in low-flow, low-gradientaortic stenosis: results of the multicenter TOPASstudy. Circulation 2008;118:S234–42.

26. MehrotraP, JansenK, FlynnAW, et al. Differentialleft ventricular remodelling and longitudinal functiondistinguishes low flow from normal-flow preservedejection fraction low-gradient severe aortic stenosis.Eur Heart J 2013;34:1906–14.

27. Eleid MF, Sorajja P, Michelena HI, Malouf JF,Scott CG, Pellikka PA. Flow-gradient patterns insevere aortic stenosis with preserved ejectionfraction: clinical characteristics and predictors ofsurvival. Circulation 2013;128:1781–9.

28. Eleid MF, Goel K, Murad MH, et al. Meta-analysis of the prognostic impact of strokevolume, gradient, and ejection fraction aftertranscatheter aortic valve implantation. Am JCardiol 2015;116:989–94.

29. Nishimura RA, Grantham JA, Connolly HM,Schaff HV, Higano ST, Holmes DR Jr. Low-output,low-gradient aortic stenosis in patients withdepressed left ventricular systolic function: theclinical utility of the dobutamine challenge in the

catheterization laboratory. Circulation 2002;106:809–13.

30. Clavel MA, Webb JG, Rodes-Cabau J, et al.Comparison between transcatheter and surgicalprosthetic valve implantation in patients withsevere aortic stenosis and reduced left ventric-ular ejection fraction. Circulation 2010;122:1928–36.

31. Hahn RT, Pibarot P, Stewart WJ, et al. Com-parison of transcatheter and surgical aortic valvereplacement in severe aortic stenosis: a longitu-dinal study of echocardiography parameters inCohort A of the PARTNER trial (Placement ofAortic Transcatheter Valves). J Am Coll Cardiol2013;61:2514–21.

KEY WORDS aortic stenosis, aortic valvereplacement, left ventricular ejectionfraction, prognosis

APPENDIX For a list of investigators,definitions of clinical events, and supplementaltables and figures, please see the online versionof this paper.