Forqueray

-

Upload

john-armato -

Category

Documents

-

view

26 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Forqueray

-

Forqueray "Pieces de Viole" (Paris, 1747): An Enigma of Authorship between Father and SonAuthor(s): Lucy RobinsonSource: Early Music, Vol. 34, No. 2 (May, 2006), pp. 259-276Published by: Oxford University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805845 .Accessed: 29/04/2014 21:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Early Music.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Lucy Robinson

Forqueray Pieces de Viole (Paris, 1747): an enigma

of authorship between father and son

In 1747, two years after his father's death,

Jean-Baptiste Antoine Forqueray (1699-1782) published the Pieces de Viole avec la Basse Continue Composees par M Forqueray Le Pere (illus.i). He did so not only in a version for the viol but

simultaneously issued a transcription of the same

pieces for harpsichord entitled Pieces de Viole

Composees Par Af Forqueray Le Pere, Mises en Pieces de Clavecin Par Mr Forqueray Le Fils. Both editions were engraved by Mme Leclair,1 the wife of Jean-Baptiste's friend and colleague Jean-Marie Leclair (1697-1764) .2 The date of publication is found on the 'Privilege GeneraF at the back of the

copy, which is dated 28 March 1747 and was in force for nine years.

Scholars working on French viol music have in the past taken the title-page at face value,3 but it is my thesis that these works, despite their

title-page, are essentially not the work of le pere, Antoine Forqueray (1671-1745), but rather of le fils, Jean-Baptiste Forqueray, and that not only were they printed in the last years of the French viol tradition but also belong there both musically and

technicalry. Four manuscript pieces de viole survive by

'Forcroi' in the Recueil de pieces de violle (F-Pn: Vm7 6296),4 which can be ascribed to Antoine and thus provide evidence ofthe father's musical style. There are four extra-musical reasons for attributing these

pieces to Antoine. First, they are credited to plain 'ForcroF, which implies Antoine, since Jean-Baptiste was habitually differentiated from his father as

Forqueray le fils.5 Second, the recueil was made

during the latter years of the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715), or shortly after; it includes 80 pieces

by Marin Marais (1656-1728) and nine by Louis de Caix d'Hervelois (C.1680-C.1755) copied in the same hand, which were all published by 1719.6 Third, the plain titles of the four pieces are charac- teristic of Antoine's generation: allemande, la

girouette, muzette and bransle. Fourth, there is a theorbo transcription of the muzette by Antoine's

colleague Robert de Visee (c.1655-1732/3) in the Vaudry de Saizenay manuscript,7 which Claude Chauvel dates between 1685 and 1716.8

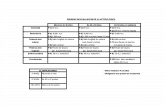

The allemande (illus.2) demonstrates the style of Antoine's pieces. The use of harmony is simple and straightforward; the harmonic progressions are often discursive, as if improvised: for example, the use of the same sequential point eight times in the second half of the piece (bars 12-20, 22-4). Antoine's modulations hold no surprises and are solely to closely related keys; as a result the allemande extends to only 26 bars. There is an

elementary attempt to unite the movement through the new Italian technique of developing melodic motives. In all four manuscript pieces the time sig- natures and tempo markings are typical of works written in the late 17th and early 18th century; no extra clues are given as to tempo or articulation save those inherent in the title.

However, Antoine's pieces demonstrate a notice- able interest in virtuosity (ex.i). There are early instances of progressive fingerings across the strings in high positions, and some sequences are fingered sequentially. This fits with the remark in the Mercure de France that Antoine Voulut faire sur la Viole tout ce qu'ils faisoient sur le Violon'9 ('wanted to do on the Viol everything that they [Italians] did on the Violin'). But there are no examples of

Early Music, Vol. xxxiv, No. 2 ? The Author 2006. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/em/cal003 Advance Access Published on 10 April 2006 259

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

i Jean-Baptiste Forqueray by Jean-Martial Fredou (1737) (private collection)

260 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

^li^J-tJ-fr f~. j, -M f~T I i fe

fl ILcM'iaitde. ? *-p

?rft

*_-^?,-i__|p>^?p^-*-4.?-?'?.

Utrcirw

pf^^^|S #7^-J.2-i-f1^"

ffipg^f^^ f^ g=t#

3-*-j?* iiE_#

? /;;:::gzzz3^fczj^l

f=T 4_-_fIgj

T l*^"^-?-#-L-IJ-^p^-^-??^-i

r r t r f w

t^f .^^

"^^^^Q 1 J* f ji * ' g?* ?-^f-$L-^^ .NwZ-^|~^-O .

f=f F^

3E

2

? t rf

'

T

2 Antoine Forqueray: atletftfrhde (F-Pn: Vm7 6296, pp. 52-3)

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 26l

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.i La girouette: Antoine's interest in virtuosity

gmsmtA?M

ilj,^l?ftirtT1ii?bfli^ga^i 4

^ ?

typically Italianate passage work and the viol writing is not strongly chordal.

Jean-Baptiste was the greatest violist of his gen- eration.10 He was Ordinaire de la Musique de la Chambre du Roy11 and performed in the Concert

Spirituel.12 He was involved in the celebrated

performances arranged by the musical fermier general (tax collector) Joseph-Hyacinthe Ferrand (1709-71),13 who in his turn was cfort ami de Mme de Pompadour'.14 When Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) came to Paris in 1737, Jean-Baptiste played the Paris Quartets with him alongside Michel Blavet (1700-68),15 Jean-Pierre Guignon (1702-64) and Prince Edouard.16 D'Aquin de Chateau Lyon wrote of Jean-Baptiste: // a tous les talens de son pere: a la plus grand execution il joint les graces les plus aimables. Les Pieces les plus difficiles ne lui coutent aucune peine, il les joue avec cette aisance qui caracterise le grand homme: tout devient sous ses doigts un chef-d'oeuvre de delicatesse & d'elegance.17

He has all his father's talents: to the most sophisticated per? formance he adds the most pleasing graces. The most difficult pieces cause him no anxiety; he plays them with that assurance which characterizes the great player: under his fingers everything becomes a masterpiece of refinement and style.

Jean-Baptiste married twice. His first wife, Jeanne Nolson (c. 1700-1740),18 was the sister-in-law of Estienne Boucon (d 1735), who in turn was father of the celebrated harpsichordist Anne Boucon

(1708-80).19 Jean-Baptiste's second wife, Marie- Rose Dubois (1717-after 1782),2? was another outstanding harpsichordist (illus.3). D'Aquin wrote of her: cOn connoit tous les talens de Madame For-

queray. sa reputation est eclatante.' (cMadame For- queray's talents are well known: her reputation is brilliant.') It seems likely that Marie Rose played a significant role in the highly idiomatic harpsichord transcriptions of the Pieces de Viole.

262 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

Three of Jean-Baptiste's remarks in the avertisse- ment to the Pieces de Viole provide a useful key to

my thesis, that the works are essentially the com-

positions of le fils. Jean-Baptiste informs the player of three highly significant facts. First, that he has

composed the bass:

J'ai juge a propos d'en faire la Basse tres simple, afin d'eviter la confusion qui se trouveroit avec la Basse des piece[s] de Clavecin quej'ai ornee autant quils [sic] ma ete possible. I thought it best to make the bass line very simple, so as to avoid any confusion with the bass ofthe pieces de clavecin, which I have made as ornate as possible.

Second, that he has fingered the pieces: Je me suis attache a bien doigter ses pieces, pour en rendre VExecution plus facile. I have endeavoured to finger the pieces carefully to make their performance easier.

And third, that in the third suite he has added three

pieces of his own:

La troisieme suite ne s'etant pas trouvee complete pour le nombre des pieces, fai ete oblige d'en ajouter trois des miennes, lesquelles sont marquees d'une Etoile.

The third suite not being found complete regarding the number of pieces, I was obliged to add three of mine; these are marked with a star.

From the first of these remarks it follows that, if the bass was by Jean-Baptiste, so too must be the elaborate continuo figuring. An analysis of the

harmony in the Pieces de Viole reveals it to be

extraordinarily bold and imaginative, using rapid modulations and abrupt key changes, with a great love of colour usually in the form of striking disson- ance (diminished 7ths, dominant 9ms, secondary 7ths and augmented 5ths) or tonal ambiguity (shift- ing modes between major and minor, or in minor keys juxtaposing sharpened and flattened 6ths).21

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

3 Marie-Rose Dubois by Jean-Martial Fredou (1745) (private collection)

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 263

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.2 La Rameau: an elliptical progression

Ex.3 La Silva: substitution of diminished 7th for the dominant

Mma^^kZIJEZ'^Mlsri?;ZIZZ3ZII_-ZESZ-

&jjgw

x

221

Ex.4 La Silva: a characteristically piquant progression

This is combined with rich decoration using appoggiaturas and suspensions, and a delight in

ellipsis?a progression omitting stages in the

argument. La Rameau demonstrates this use of elliptical

progression. Starting in bar 12 (see ex.2), the har- mony moves from El> major via a diminished 7th to F minor; an expectation is then set up of moving to G minor on the first beat of bar 14, following the

sequence ofthe last two bars, but instead this step is omitted, by moving immediately to a cadence in

264 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

C minor where the dominant chord is elided with the tonic. The colour of substituting a diminished 7th chord for the dominant is also enjoyed, as in the opening bars of La Silva (ex.3). Bars 25 and 27 (ex.4) ofthe same piece illustrate a characteristic- ally piquant and unpredictable progression: starting in C minor the harmony moves to the dominant, which then shifts to the minor mode and adds the

sharpened 6th. From here a plagal cadence is made into D minor and then by means of a false relation (a! contradicted by a\>) the harmony is directed

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.5 Jupiter. unresolved dissonance

Ex.6 Jupiter. appoggiatura-laden French 6th (with flattened 5th)

Ex.7 Jupiter. augmented-6th chord requiring five notes of the whole-tone scale

back to the subdominant of C minor to enable the final cadence to be achieved.

The dramatic king of the gods, Jupiter, elicits harmony to excite the passions. Even within the rondeau subject unresolved dissonance is found, such as the d! on the last semiquaver of bar 5 (ex.5), which is left abandoned in mid-air. In the third couplet (ex.6) a dominant chord (key F minor) is approached from an appoggiatura-laden French 6th (with the flattened 5th); the corresponding

passage towards the end of that couplet (ex.7) uses an even more exotic augmented 6th, uniquely utilizing five notes of the whole-tone scale.22 In the fourth and final couplet Jupiter, thoroughly enraged, hurls down thunderbolts, and the listener is further shocked by means of some ungram- matical harmonic surprises (ex.8): departing from the tonic, C minor, the couplet moves abruptly without modulation to Al> major. From here it modulates by means of a typically chromatic bass to E\> major, but the next move is to jump without warning or cadence to B\> minor; after establishing the key firmly there for four bars the bass moves

by descending 4ms, but with no sharpened leading notes to reassure the listener as to keys, until the arrival on the dominant, G major.

Fascinatingly d'Aquin, writing in 1752, specifically comments on Jean-Baptiste's characteristic har? monic boldness and use of strange progressions:

M. Forqueray a ... des phrases musicales d'un nouveau tour... La fagon d'employer et de placer les accords les fait paroitre singuliers & nouveaux.23

M. Forqueray uses ... musical language in a new direction ... His way of using and positioning chords makes them appear unconventional and new.

The striking harmonic progressions in the Pieces de Viole are strongly akin to those of Leclair24 and, indeed, of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)?the ?Grand Rameau', as Jean-Baptiste described him, whose musical 'noblesse', 'belle harmonie' and 'sen- timent' he greatly admired.25 Conversely they are not typical of the writing of the era of Louis XIV, when Antoine flourished. Leclair, in particular, shows a penchant for juxtaposing modes similar to that found in the Pieces de Viole, as can be seen in the Largo of Sonata 10 in his Quatrieme livre de sonates a violon seul avec la basse continue (Paris, !743) (ex.9); it was a trait noted by Le Blanc, who condemned Leclair's 'juremens execrables, lors du passage du Ton Mineur au grand Ton Majeur' ('heinous blasphemies, in moving from minor to major').26

The Pieces de Viole show a taste for rapid modulation. Within one binary movement the work commonly moves fully to five or six keys, while those of Antoine's generation rarely move to

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 265

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.8 Jupiter. ungrammatical harmonic surprises

!*FtitrfJL47 . ^ti^Mfrflft

! I f f

l!~ltf?'W1

IJI

ggJ,tp iJ , Ijj

Z_?_L r^f-F

J3=igU^: '

Ex.9 Leclair, Sonata 10 (Paris, 1743), Largo: juxtaposition of major and minor modes

'""',""?'" 'i^i?pi?ir'i?|i?'-?N>l|^?iii?nifi?.j 1 ?l. m.ii.iii.iii , iJLt, Xw. imiilf 1 ^J^^.^^^a^

more than three or perhaps four. For example, the

binary movements in Marais's first three suites of his Pieces de Violes (Paris, 1711) average a mere 19 bars, whereas the binary movements of the first five sonatas of Leclair's Quatrieme livre de sonates a violon seul avec la basse continue (Paris, 1743)? which like the Pieces de Viole modulate rapidly? average 48 bars. The binary movements in the Pieces de Viole average 43 bars?a length in keeping with

Jean-Baptiste's generation.27

266 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

Jean-Baptiste's decision to make the bass ctres simple' is characteristic of the highly virtuoso sonatas of the second quarter of the 18th century, notably those of Leclair. The continuo support is left plain to set off and complement the extremely elaborate solo part. This is in contrast to the pieces de viole of Marais, in which the continuo bass plays a much greater contrapuntal role (ex.io).

The second comment from the avertissement? that Jean-Baptiste has carefully fingered the

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

basse de viole

basse cont.

Ex.io Marais, Charivary (Paris, 1711): contrapuntal use ofthe bass line

tres vivement

&

m pe

w

6 i 9 8 7 6 7

m

Ex.11 La Guignon: mid-i8th-century use of the nouvelle methode

pieces?is substantiated by an examination of the left-hand technique in the Pieces de Viole. This reveals it to be strongly influenced by the most advanced principles of the mid-i8th-century nouvelle methode developed by the French violinists at this date.28

Exponents of the nouvelle methode wanted to create brilliant virtuoso effects with one impression blending into the next so as to achieve the same

flexibility and subtlety that characterize the human voice. Le Blanc described how:

Ici on ne demeloit ni le tire ni le pousse. Un Son continu se faisoit entendre, quon etoit maitre d'enfler ou diminuer, comme la voix?9

Here [in the new style] one could distinguish neither the down bow nor the up. One continuous sound could be heard, which [the player] was free to swell or diminish, like the voice.

The equivalent in writing for the left hand is the

mid-i8th-century development of upper positions in preference to running up and down the chanterelle?the top string that in the works of Marais, a generation earlier, was used literally for

singing the melody.30 This latter practice is disdain-

fully described by Le Blanc as 'sauts de Niagard; such fingering he felt to be ugly and showed an

ignorance of the fingerboard.31 Jean-Baptiste was at the forefront of this new technique, which he named

the petit manche?2' This was the practice of lying the first finger across three strings above the frets,33 and in around 1768 he wrote at length about its import? ance in the first of his letters to Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia.34

Il resulte de cette parfaitte connoissance beaucoup de bonnes choses: f le beau son qui est Vame des instrumens a archet, 20 la facilite dejouer tout ce quil y ade plus difficile, meme ce que peut executer le violon, la flute et le clavessin, 30 le Repos de la main gauche qui est beaucoup moins fatiguee sur le petit manche que sur le grand qui ne sert que pour les accords, pour la musique qui descend, Vaccompagnement, et toute musique ordinaire qui se trouve sur les clefs de fa et de viole?5

There follows from this perfect understanding [of the petit manche] many good things: (1) the beautiful sound which is the soul of bowed instruments, (2) the facility to play all the most difficult things, even those that can be played on the violin, flute and harpsichord, (3) the position of the left hand is much less tiring on the petit manche than on the grand, which serves only for chords, for when the music goes low, for continuo playing and all ordinary music which lies in the F and viol clefs.36

A thorough exploration of the petit manche is one of the most striking features of the Pieces de Viole. The mid-i8th-century nouvelle methode is such an

integral part of the Pieces de Viole that a strong preference to stay in a high position is shown if it reduces the need to move the left hand. Ex.11, from La Guignon, illustrates this technique;

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 267

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.i2 Marais, Plainte (Paris, 1711): preference for the chanterelle

14 . ^ . ^> e

i

^ 4. r? xT 1

T

m

& ^4^-^

-3. I

LQ " o

Ex.13 Chords of C major and minor found in the Pieces de Viole

^ te ^S ~r?- ~n-

H\ 1 >H n; ^?

y iiii II 0 ?k n_ 3 ?>

~n~ ^?= s s ~yr- Tf~ 1rxr

a ** ?g= =8= 8= l^1 ?!>? "4I>? ^B= 0 XT XT

^

3^ t*>- 4 Ii

=8= =8= =8= _

1 o

srfW 3^

-o- -4-e- ~cr ~tt-

contrast this with Marais's fingering in his Plainte of 1711 (ex.12).

One result of this use ofthe nouvelle methode was the wide range of new and unusual tone colours that are so peculiar to the Pieces de Viole. Experi- mentation with the upper positions in turn led to an exploration of an exotic new range of chords not only situated wholly in the petit manche but also combining open strings with high positions.

Unlike the relatively restricted use in earlier viol works, 260 different chord patterns are found in the 32 pieces de viole. In addition to a broad variety of triads and 7th chords on each degree of the scale, 42 different arrangements of diminished chords are explored and five contrasting augmen- ted triad positions. These various permutations

268 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

demand considerable acrobatics from the left hand, which must stretch and contract for the diverse and intricate fingerings. Ex.13 illustrates the range of chords of C major and minor found in the Pieces de Viole; the many unusual chord patterns serve as a representative cross-section ofthe chordal spec- trum. The boldly creative and individual approach to chord voicing owes little to that found in the bass viol works of even the closest predecessors to the Pieces de Viole, such as the publications in the latter half of the 1730s by Roland Marais (c.1685- c.1750) and Charles Dolle (/Z.1735-55); rather it is stimulated by the inventiveness of contemporary violinists, notably Leclair, and adapted to the vioFs unique potential by a player who understood it utterly.

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Ex.i4 La Silva: dense and virtuoso ornamentation

If the fingering is characteristic of the mid-i8th

century, one is led to wonder whether Jean-Baptiste was also responsible for adding ornamentation. The

symbols found in the Pieces de Viole are the same as those used by Marais and his contemporaries; the distinguishing feature is the ornamentation, which is used more densely, alongside other virtu? oso technical feats and in complex, even outrageous situations (ex.14). This emphasizes virtuosity in exa- ctly the same way as in the movements by Leclair.

The third point that Jean-Baptiste made in his avertissement?that the three pieces marked with a star in the third suite are his own?gives the opportunity to compare Jean-Baptiste's starred compositions with those said to be by Antoine.

An examination of the first of the starred pieces, La Angrave (illus.4), reveals an abundance of the stylistic fingerprints which characterize the

remaining pieces. First, its length of 40 bars and its

tight use of motivic material is typical of many other

binary movements in the collection.37 It employs the same material (transposed) to open both halves of the movement, and the penultimate bars of each half are similar. This practice is common to almost all the other binary movements in the Pieces de Viole but uncommon in pieces de viole of the previous generation; it is not found in the manuscript pieces by Antoine discussed above.38 La Angrave also makes a striking use of pedals both in the bass (bars 7-10) and in the melodic line (bars 11-13); once again a frequent and imaginative use of pedals is a distinctive feature of the collection as a whole.39 Sudden switches to the minor mode (bars 10-13 and 37-9) are another remarkable trait of the move? ment; this type of tonal ambiguity is again common to the entire publication.40 The movement also abounds in rich sequences with many 7th and 9th chords. It sports an augmented chord in bar 23 and many audacious diminished 7ms,

most notably one such chord repeated emphatically seven times just before the conclusion; but such harmonic language is entirely representative of the

remaining works in the collection.41 Bars 28-30 of La Angrave exploit successive large leaps, which were made possible by the new mid-i8th-century fingering method. La Angrave also employs highly ornamented chords (bars 25-7 and 37-8), another imprint of the collection as a whole.42

Interestingly the titles ofthe pieces in the Pieces de Viole, which we may assume were largely if not

entirely added by Jean-Baptiste,43 predominantly bear the names of his contemporaries: Rameau; the violinists Leclair, Giovanni Battista Marella

(//.1740s) and Guignon; Charles-Francois Clement (0720-after 1789), who dedicated his Sonates en trio pour clavecin et un violon (Paris, 1743) to Jean-Baptiste and Marie-Rose; Cottin, a subscriber to Telemann's Nouveaux Quatuors (Paris, 1738);44 Bouron, the Forquerays' solicitor, whose name

appears on family documents between 1736 and 1760; Pierre Buisson, the husband of Jean-Baptiste's sister Charlotte-Elisabeth (1697-after 1745);45 Dr Theodore Tronchin, a member of La Poupliniere's circle;46 and the fermiers generaux Regard D'Aubonne, Louis-Philippe Duvaucel (d 1794) and Ferrand. La Couperin and La Forqueray are more

ambiguous. Was La Couperin dedicated to Francois (1668-1733) or his daughter, Marguerite-Antoinette (1705-C.1778), who held a position at court at the same time as Jean-Baptiste? The character of the piece, marked 'Noblem1 et Marque', perhaps implies the father.47 Likewise, which member of the Forqueray family is intended? Marked 'Vivement et d'aplomb' and as a piece emphatically virtuoso and Italianate, La Forqueray seems an

appropriate dedication to Antoine but it could also be Jean-Baptiste's second cousin Nicolas-Gilles Forqueray (1703-61), who was a highly respected

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 269

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

* La Anq:rave.

/? ? 1 _' J J" 1 1_ i I i

4 Jean-Baptiste Forqueray: La Angrave (Paris, 1747)

270 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

organist, holding posts at Saints Innocents, St Laurent, St Eustache and St Merry.48 La Regente can unambiguously be pinned down to Antoine's

patron, Philippe d'Orleans (1674-1723); the Regent, a violist himself, not only left Antoine his viol but also personally paid off the potentially ruinous loss of 100,000 livres that Antoine had incurred investing in the ill-fated Mississippi company.49 However, Jean-Baptiste taught d'Orleans's son, Louis (1703- 52),5? and as a musicien du Roi had his own strong links with the Orleans family.

Thus from Jean-Baptiste's own statements in the avertissement we learn that Jean-Baptiste added and figured the bass, and fingered the viol part, which is not an insignificant contribution. An examination of Antoine's manuscript pieces and the Pieces de Viole reveals a huge stylistic evolution which though not impossible seems highly unlikely to have occurred in a composer between the age of about 40 and his death at 74. And, while it can be

argued that Antoine could have come into contact with, for example, Leclair's works in the 1720s, his decision in 1731 to retire quietly outside Paris to Mantes51 does not square with a composer fascin- ated in exploring the latest compositional tech?

niques. Indeed, his obituary paints an entirely different picture: Mr. F. voulant mettre un intervalle entre La vie et la mort dans un age ou il pouvait encore jouir de La gloire d'etre Le premier dans son art ... cest la [a Mantes] que, soutenu par les principles de Religion, il a tranquillement attendu sa derniere heure.52

As Mr. F. wished to put an interval between life and death at a time when he could still enjoy being the first in his art ... it was [in Mantes] that he waited quietly for his last hour, sustained by the principles of religion.

It is noteworthy too that contemporary sources refer to Antoine uniquely as a player and, unlike

Jean-Baptiste, never as a composer. The colossal advance in the required performance techniques between Antoine's manuscript works and the Pieces de Viole is harder to explain and furnishes a strong counter-argument. Finally there is the confirmation of Jean-Baptiste's own three pieces 'marquees d'une Etoile', which are compositionally indistinguishable from the rest of the collection. This combined evid? ence reinforces my proposal that Jean- Baptiste played the dominant and vital role in the

composition of the published Pieces de Viole, and therefore that they are in effect mid-i8th-century works representing the end of the French viol tradition.

However, in view of Jean-Baptiste's claim that the asterisked pieces were his own, it would seem that the remaining 29 pieces had at least a genesis in Antoine's work?albeit so thoroughly updated by the son as to obliterate the original. This raises the

question of why Jean-Baptiste took the trouble to distinguish between his father's work and his own. Was he perhaps worried about accusations of plagi- arism from those who already knew the originals? If Jean-Baptiste used material from his father as a starting point, why was he short of music in D

major (the key of the suite to which he adds three movements marked with a star)? This is the key of the viol's tuning: in Marais's ceuvre of 596 published pieces de viole the vast majority are in D.53

Finally, why should Jean-Baptiste, the greatest violist of his generation, publish what are essentially his avant-garde mid-i8th-century pieces under his father's name? Was it filial homage? Or did he believe that his father's name would give a commer? cial advantage to an instrument whose popularity was waning? The mystery deepens when one learns that the father, likewise a phenomenal player, became so jealous of his son that he had him first imprisoned and later banished.

Antoine, described by his wife as of a 'naturel violent et emporte' (Violent and quick-tempered disposition'), beat his wife54 and son, and kept them penniless while he travelled around in a sedan chair.55 Antoine and his wife separated in 1710, and the children56 lived with their father in the rue Courteau-Villain, where he continued to beat

Jean-Baptiste. In 1715 Antoine had Jean-Baptiste imprisoned at Bicetre, claiming that his son had 'une inclination pour le jeu des femmes & le vol dans les maisons ou son pere lui donnoit entree' (can inclination to play around with women and to steal from the houses where his father had given him an entree') and believing that cune vive cor- rection pourroit changer un si malheureuse

Temperament' (ca short sharp shock would change such an unfortunate character').57 Then in 1725 Antoine had his son banished from the kingdom

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 271

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

for ten years on pain of death, once again alleging that Jean-Baptiste lived a debauched life and was a thief.58 Fortunately Jean-Baptiste, now aged 26, had pupils of influence prepared to stand by him and provide evidence of his good character. Mon- sieur de Monflambert recommended that Antoine's accusations should be looked into again as there was reason to believe that they were false:

la cruaute du pere est visible, cest un fils quil [sic] a abandonne a quinze ans, et qui depuis dix ans na pas recu [sic] un sol de luy, sa correction et sa justice paternelle ne connoissent d'autres peines qu'un exil hors du royaume sous peine de la vie, une prison de quelques mois ne satisfairoit point sa barbarie & seroit a charge sa bourse. une proscription remplit ses desseins, son gout, et sa jalousie contre le merite personnel de son propre fils.59 The cruelty of the father is obvious. This was [a case of] a son abandoned at 15, and who in the last ten years has never received a sou from him [Antoine]. His [Antoine's] correction and his paternal justice knew no less punishment than exile from the kingdom on pain of death; mere prison for several months did not satisfy his barbarity and would have cost him financially. Banishment satisfied his scheming, his inclination and his jealousy against the personal merit of his own son.

These letters appear to have secured Jean-Baptiste's release; the banishment order was lifted on

3 February 1726.60 The relationship between father and son from

this point is capricious. Antoine paid considerable attention to writing his will. He excluded his son in 1729, but revoked the will in 1732. He wrote

Jean-Baptiste in again in 1736, but once more revoked the will in 1741. Finally in 1743 Antoine left

Jean-Baptiste 20,000 livres and some extremely valuable viols, but the bulk of his considerable fortune went to his daughter, Charlotte-Elisabeth. None of the family attended Antoine's funeral.61

So after this extraordinarily painful and malfunc-

tioning relationship between Forqueray pere et fils, was there a reconciliation such that Jean-Baptiste wished to pay filial homage to his father? While the bulk of Antoine's fortune went to his daughter, the 20,000 livres left to Jean-Baptiste was a huge sum of money.62

In the dedication to the Pieces de Viole 'a Madame Henriette de France',63 Jean-Baptiste writes:

L'ouvrage que je prends la liberte de vous offrir a merite afeu mon pere la reputation dont il a joui pendant sa vie, et la Protection que

272 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

vous voules bien lui accorder, Madame, va lui assurer Vimmortalite. La Viole, malgre ses avantages, est tombee dans une Espece d'oubli, votre gout, Madame, peut lui rendre la celebrite quelle a eue si longtemps, il peut exciter Vemulation de ceux qui cultivent la Musique; Pour moi, Madame, un motifplus pressant m'engage a redoubler mes veilles. Le bonheur que j'ay eu de vous voir aplaudir a mes foibles talens va renouveller I'ardeur de mon zele: heureux si par mon travail je puis contribuer a vos amusemens.

The work, which I have taken the liberty to offer you, merited the high reputation which my late father enjoyed during his life, and the patronage that you were gracious enough to give him, Madame, assures him immortality. The viol, in spite of its merits, has become a forgotten species; your taste, Madame, can give it back the fame that it has had for so long; it can excite emulation from those who cultivate music. For me, Madame, a more pressing reason encourages me to intensify my vigil. The pleasure that I have had from seeing you applaud my feeble talents will renew the ardour of my zeal: happy if by my work I can contribute to your recreation.

In an age when contemporary music was valued above music from the previous generation, it is remarkable that Jean-Baptiste should have wished to publish pieces de viole in his father's name. Is it

significant that in the dedication Jean-Baptiste con- cludes by referring to 'mes foibles talens' and 'mon travail'? Likewise in the avertissement he writes:

Si le public regoit favorablement ce Premier Livre, son sufrage m'encouragera a lui en presenter d'autres, dont le gout, la force et la variete ne se trouverontpas moins rassembles que dans celui cy.

If the public receives this First Book favourably, their approval will encourage me to present others, the taste, strength and variety of which will be found no less combined than in this one.

Is this an acknowledgement of Jean-Baptiste's substantial contribution to the publication?and his desire to compose more? Or was, indeed, Antoine's name still so highly respected in 1747 that it was a commercial advantage to use it to restore the fortunes of the viol (and perhaps to aid those publishing music for the instrument)? The dedication to the Pieces de Viole states plainly that the viol's standing was close to Jean-Baptiste's heart. The viol was his chosen instrument: he could have migrated to the cello like many of his con-

temporaries.64 And Jean-Baptiste did have a shrewd eye for business: he simultaneously brought out the beautifully arranged version for the very popular harpsichord, and also suggests that one might play the Pieces de Viole on the pardessus de viole65 (which

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

was highly in vogue with court ladies). He had a substantial amount of money in property,66 and in his 6os became a successful arranger and publisher.

Despite Jean-Baptiste's horrendous first 26 years, the evidence points to some sort of a final reconcili- ation between father and son; perhaps we should take Jean-Baptiste's remark in his avertissement at face value: that he wished to ensure Antoine's

immortality. The pieces were published 21 months after Antoine's death, which is an appropriate

amount of time to make the collection, to arrange them for harpsichord, and to engrave and bind both volumes. And happily, if this was indeed his aim, he has certainly succeeded in preserving it to this day. Nonetheless, and for whatever reason, it is remarkable and enigmatic that Jean-Baptiste, an ordinaire de la musique de la chambre du Roi, did not choose to publish what are essentially his

highly progressive, mid-i8th-century pieces under his own name.

Lucy Robinson is Head of Postgraduate Programmes and Research at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and a professional viol player. [email protected]

Many thanks to Graham Sadler and Andrew Wilson-Dickson for reading early drafts and assisting me in presenting my case more persuasively. i Louise Leclair (1700-C.1774) (nee Roussel). Mme Leclair remained Jean-Baptiste's engraver when he collaborated with Louis Balthazard in a publishing venture in 1760. 2 Jean-Baptiste was a witness to Leclair's second marriage in 1730 with Andre Cheron and Leclair's patron, Joseph Bonnier de la Mosson, Marquis du Mesnil, Marechal general des logis des Camps & Armees du Roi, Tresorier general des Etats de la Province du Languedoc: L. de La Laurencie, Vecole francaise de violon, du Lully d Viotti: etudes d'histoire et d'esthetique (Paris, 1922-24; R/1971), i, pp.274-6, 284. Both Leclair and Cheron lodged with Bonnier during the late 1720s and early 1730s. The fact that Cheron and Bonnier were both witnesses at Jean-Baptiste's marriage in 1732 shows how closely Jean-Baptiste was associated to Leclair's circle at that time: Forqueray family papers cited in L. Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition (PhD diss., Cambridge U., 1981), p.100. 3 B. Schewendowius, Die solistische Gambenmusik in Frankreich von 1650 bis 1740 (Regensburg, 1970); M. Urquhart, Style and technique in the pieces de violes ofMarin Marais (PhD diss., Edinburgh U., 1970); H. Bol, La basse de viole du temps de Marin Marais et d'Antoine Forqueray (Bilthoven, 1973); B. McDowell, Marais and Forqueray:

a historical and analytical study of their music for solo basse de viole (PhD diss., Columbia U., 1974); A. Otterstedt, Die Gambe (Kassel, 1994), trans. H. Reiners and revised as The viol (Kassel, 2002). 4 Pp.52-55, 74-75, uo. For a more detailed discussion of these manuscript pieces, see Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.116-25. 5 The same nomenclature is found for the two Marais: plain 'Marais' implies Marin; his son Roland is referred to as Marais lefils. 6 Those by Marin Marais are to be found in his first four books which were published by 1717, and those by Caix d'Hervelois in his first two books published by 1719. There are also 11 works by Roland Marais in a different hand and almost certainly of a later date. (They come from both his collections of pieces de viole, the second of which was published in 1738.) 7 La Muzette de Mr Fourcroy mise par Mr de Visee. 8 Introduction to the Minkoff facsimile (Geneva, 1980). De Visee also transcribed La Venitienne de Mr Fourcroy, which does not survive in its original form. 9 August 1738, pp.1733-4. 10 Ancelet, Observations sur la musique, les musiciens, et les instrumens (Amsterdam, 1757), p.23. 11 Jean-Baptiste officially took over his father's position on 14 September 1742 although the certificate signed by Louis

XV informing the court of Jean-Baptiste's succession also referred to his court service before that event: Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, p.104. Furthermore, Jean-Baptiste is recorded as 'officier du Roy' on Leclair's marriage contract dated 8 September 1730. 12 He performed a 'Quatuor' by Telemann in the series on five occasions in June 1745, with Blavet (flute), Marella (violin) and L'Abbe (cello); see C. Pierre, Histoire du Concert Spirituel, 1725-1790 (Paris, 1975), p.251. Judging by the line-up of instrumentalists and Jean-Baptiste's acquaintance with Telemann and the Paris Quartets, the 'Quatuor' seems likely to have been one of the Paris Quartets. 13 Ferrand rated Jean-Baptiste ?aussi admirable sur sa basse de viole que Leclair avec son violon', M. Bourges, 'Souvenir d'un octogenaire', Gazette musicale de Paris (Paris, 1845), p.203. 14 Due de Luynes, 'Memoires', 15 fevrier 1748, in N. Dufourcq, La musique a la cour de Louis XIV et de Louis XV d'apres les memoires de Sourches et Luynes, 1681-1758 (Paris, 1970), p.127. 15 Blavet was a witness at Jean- Baptiste's second marriage: see Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, p.102. 16 'Die Bewunderungswiirdige Art, mit welcher die Quatuors von den Herren Blavet, Traversisten; Guignon,

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 273

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

Violinisten; Forcroy der Sohn, Gambisten; und Edouard, Violoncellisten, gespielt wurden, verdient, wenn Worte zulanglich waren, hier eine Beschreibung', from Telemann's autobiography in J. Mattheson, Grundlage einer Ehrenpforte (Hamburg, 1740), p.3. 17 P. L. d'Aquin de Chateau Lyon: Lettres sur les hommes celebres dans ... les beaux arts (Paris, 1752), i, pp.143-4. 18 Marriage contract in the Forqueray family papers. See also L. Forqueray, Les Forqueray et leurs descendants (Paris, 1911), pp.58-9, and Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.99-100. 19 Anne Boucon later became the wife of Jean-Joseph Cassanea de Mondonville. Etienne Boucon was described as a 'grand amateur de tous les arts', Necrologe des hommes celebres (1773), Archives Nationales 0 671, cited in L. de La Laurencie, Vecolefranqaise de violon, i, p.387; he was guardian of Jeanne Nolson from 1706, and at the time of the marriage Jean-Baptiste was also living in the Boucon family home. Both Anne and her father were witnesses at Jean-Baptiste's marriage. Rameau was a member of the Boucon family circle and taught Anne the harpsichord: see G. Sadler, 'Rameau, Jean-Philippe', New Grove II. 20 Marriage contract: Minutier Central des Notaires de Paris, I, 403. See also M. Benoit and N. Dufourcq, 'A propos des Forqueray', Recherches sur la musique franqaise classique, viii (1968), p.231 and Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.102-3. According to La Borde, Marie-Rose came of a noble family from Franche-Comte: Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne (Paris, 1780), iii, p.509. 21 For a fuller analysis of Jean- Baptiste's harmony, see Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.186-206. 22 There is no mistake here as the viol fingering confirms the notation.

23 D'Aquin, Lettres sur les hommes celebres, i, pp.143-4. It is clear from the context that d'Aquin is writing about Jean-Baptiste.

24 See R. E. Preston, 'The treatment of harmony in the violin sonatas of Leclair', Recherches sur la musique francaise classique, iii (1963), pp.131-44. 25 In a letter (c.1768) to Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia; Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, BPH Rep. 48 J Nr. 327, fol.36/37; facs. Methodes & traites viole de gambe: France, 1600-1800, ed. P. Lescat and J. Saint-Arroman (Courlay, 1997), p.215. 26 Le Blanc, Defense de la basse de viole contre les entreprises du violon et les pretentions du violoncel (Amsterdam, 1740), p.50. Perhaps it was just as well that the Pieces de Viole were not published until after Le Blanc's polemic or, as a strong supporter ofthe viol and the Forquerays, the abbe would have been put into a quandary. 27 For a fuller discussion, see Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.151-6. 28 This is Le Blanc's term: see Le Blanc, Defense de la basse de viole, pp.122-6. 29 Le Blanc, Defense de la basse de viole, p.48. 30 Most French pieces de viole are fingered. 31 'On evite ces sauts de Niagara si disgracieux a voir dans le transport de la main, lesquels supposent une ignorance du Manche', Le Blanc, Defense de la basse de viole, p.123. 32 See facsimile (Courlay, 1997), p.208. 33 The viol equivalent to the cello's thumb position?and possibly the inspiration for it. 34 Prince Friedrich Wilhelm invited Jean-Baptiste to Potsdam. Jean-Baptiste declined on the grounds of 'mon age avance joint a quelque infirmites', he also refers to 'une maladie serieuse de ma femme et de moy': see facsimile (Courlay, 1997), pp.208, 219, but as a substitute he entered into correspondence with the prince, discussing viol technique. In the 1770s Prince Friedrich Wilhelm switched to the cello: it is fascinating that the inspiration for Mozart's 'Prussian' Quartets and the dedicatee of Beethoven's op.5 cello sonatas started out as a violist.

35 See the facsimile (Courlay, 1997), p.209. 36 Jean-Baptiste's Viol' clef is the alto. Seventeenth-century manuscript pieces de viole, such as those by Sainte- Colombe, occasionally use the bass clef with F on the middle line. When Jean- Baptiste writes in the petit manche he often uses the soprano clef. 37 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.157-60, 172-5. 38 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.157-60. 39 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.208-9. 40 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.199-201. 41 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.188-98. 42 See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, p.304. 43 La Couperin and La Regente were perhaps titles given by Antoine. 44 Jean-Baptiste himself was another subscriber, with Belemont, de la Tour and Tronchin. 45 Forqueray family papers, L. Forque? ray, Les Forqueray, p.65. 46 G. Cucuel, La Poupliniere et la musique de chambre au xvm siecle (Paris, 1913; R/1971), p.41. 47 In some cases Jean-Baptiste does appear to have characterized his dedicatees. For example, La Rameau is particularly rich harmonically and marked 'Majestueusem* ', while La Guignon, marked 'Vivem* et detache', is extrovert and virtuoso, befitting that brilliant, if truculent, violinist. 48 Discussing organists, Ancelet (Observations, p.26), rated him alongside [A.-L.] Couperin, Marchand, Calvieres, Rameau, Daquin, Dornel, Clerambault and Balbatre, as having 'la plus grande reputation'. 49 Anonymous i8th-century obituary in the Forqueray family papers: see L. Forqueray, Les Forqueray, p.5. It was the Regent who, to pay off the enormous debt resulting from the War of the Spanish Succession, had invited the Scottish financier John Law to be Controlleur General des Finances. In

274 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

(Rene SlotSoom Maker of historical bowed instruments

Renaissance and baroque viols Violone

Cello, baroque and classical Double bass

Odijkerweg 4 3709 JH Zeist - NL

reneslotboom@planet. nl www.reneslotboom.nl

$fa /tfl

THE

UNIVERSITY

OF

SOUTH

DAKOTA

offers the Master of Music degree with a concentration in the history of musical instuments, utilizing the staff, collections, and facilities of the National Music Museum & Center for Study ofthe History of Musical Instruments. Enrollment limited to 6 students a year; tuition assistance available; fully accredited.

For information, write: Dr. Andre P. Larson, Director National Music Museum 414 East ClarkStreet Vermillion, SD 57069-2390 USA www.usd.edu/smm

1717 Law set up the Compagnie de la Louisiane ou d'Occident, shares for which at one point were selling at 40 times their nominal value; it crashed in 1720 due in part to English spies spreading doubt about the scheme. 50 Jean-Baptiste writing to Friedrich Wilhelm, c.1769: 'le Pere de Monsieur le Due D'orleans d'apresent auquel j'avois l'honneur d'enseigner'?the 'current' Due d'Orleans was Philippe-Egalite (1747-93), son of Louis and grandson of the Regent; facsimile (Courlay, 1997), p.221-2. 51 M.-T. La Lalague-Guilhemsans, Une famille de musiciens francais: les Forqueray aux XVir etXVIIf (diss. Diplome d'archiviste paleographe, Paris, Ecole de Chartes, 1979), p.172. Antoine acquired a house in the rue de la Madeleine, in the parish of Saint- Maclon in 1731. His obituary wrongly puts the date as 1727. In 1730 Antoine wrote to the king requesting that Jean- Baptiste should succeed to his court position as he wished to retire: Archives Nationales, o'337, p.35, dated 28 Jan 1730. 52 Forqueray family papers; see L. Forqueray, Les Forqueray, p.6. 53 Antoine's anonymous obituary states that he left 'environs 300 pieces de viole': Forqueray family papers. 54 Henriette-Angelique Houssu, who came of a family of organists and was herself a harpsichordist. 55 Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, pp.84-8. 56 In addition to Jean-Baptiste and Charlotte-Elisabeth there was a second daughter, Elisabeth, born about 1702; she was ill from c.1718 and died in 1736. 57 F-Pa: Archives de la Bastille (1725), Dossier 10620, no.367. The politician, le Comte de Mirabeau (1749-91), and the violinist, Joseph-Barnabe L'Abbe le fils (1727-1803), suffered the same fate at the hands of their respective fathers. See Robinson, The Forquerays and the French viol tradition, p.96. 58 Bastille, Dossier 10620, no.367. 59 Bastille, Dossier 10620, no.376. 60 Bastille, Dossier 10620, nos.381, 383. 61 Lalague-Guilhemsans, Une famille de musiciens frangais, pp.172-4.

Forqueray

Integral

The complete five suites of Jean-Baptiste (Antoine] Forqueray Played by Lorenz Duftschmid on an original Basse de Viole by Nicolas Bertrand (Paris, 1699) at Forqueray's pitch, A=392Hz

With Thomas C Boysen, Theorbo Christoph Urbanetz, Bass Viol Johannes Haemmerle, Harpsichord

Four-language booklet by Lucy Robinson

2 CD Pan Classics/CH set available from

University of Edinburgh

St Cecilias Hall

Museum

Rodger Mirrey Collection Special edition of Soundboard,

bulletin ofthe Friends of St Cecilia's Hall, to mark the donation of 22 instruments

Edinburgh Festival Fringe Concerts

15-24 August 2006

Details of all items for sale plus concert programmes:

www. russellcollectionfriends. org Or from the Publications Officer,

St Cecilias Hall, 220 Cowgate Edinburgh EH1 1LJ

Friends of St Cecilias Hall

EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006 275

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

-

TUNING SET ? Especially suited for the

professional tuning of pianos, harpsichords, organs, etc.

? 15 hisiorical temperaments ? 5 piano tuning programs ? Programmable memories ? Pitch between 380 and 470 Hz ? High precision-absolute

reliability in critical cadences and background noises as well

? Instruciions in English, French,., ? Auraciively

priced ? Norisk: 30day$ j

nioney-back* guarantee if dissatisfied

Marc Vogel Harpsichord Parts Tel. *49 7745 9194-30, Fax -36

www.vogel-scheer.de

For Sale

Clavichord by Jean Tournay after J.C.G. Schiedmayer built in 1998; unfretted FF-f3 L 163 W 47.5 H 79.5 cm strung in

brass and iron This is an extremely

expressive concert instrument

by one of the most important builders, well suited for

keyboard music from Bach to

early Mozart. The instrument's location is near Frankfurt (Main). Price: EUR 8,000,

excluding shipment. Photographs and details

available on request from: Michael Zapf+49 172

6996194 [email protected]

62 For example, a top-of-the-market viol cost 100 livres, and a normal one 10 to 20 livres. 63 Princess Henriette-Anne (1727-52), the younger twin daughter of Louis XV; Jean Nattier's portrait of her playing the viol hangs at Versailles. Her sister Adelaide (1732-1800) likewise played the viol, and a copy of the Pieces de Viole survives beautifully bound with gold stars tooled into the leather bearing her coat of arms (F-Pn, Res F 264). 64 Six years earlier Corrette had seen fit to provide a chapter in his Methode theorique et pratique pour apprendre en peu de tems le violoncelle dans sa perfection (Paris, 1741), pp.43-5: 'Utile a ceux qui savent joiier de la Viole, et qui veulent apprendre le Violoncelle'.

65 He states on the title-page, 'Ces pieces peuvent se jouer sur le Pardessus de Viole'; however, the pieces are not well suited to the pardessus, and would require considerable arranging. 66 By 1740 he owned a sumptuous apartment in the rue Croix des Petits Champs in the heart of Paris, close to the Louvre and the Palais Royal; his marriage to Marie-Rose brought him a loge (box) at the Theatre de la Foire (at the Foire Saint-Germain) and a house at Fontenay-aux-Roses, after which he bought a number of other properties, including one on Isle-Adam (where he worked for the prince de Conti).

Early Music

Coming in 2006

Alexander Agricola (d.1506)

anniversary articles by

Rob Wegman, Fabrice Fitch,

Jennifer Bloxam and Warwick Edwards

Simon Polak

Traverso

Z3_.-?_zi?G> ? ?t^5~~n Biezendijk 32 www.earlyflute.com 5465LD Zijtaart [email protected] The Netherlands +31 6 53323203

276 EARLY MUSIC MAY 2006

This content downloaded from 160.253.129.16 on Tue, 29 Apr 2014 21:46:33 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Article Contentsp. 259p. 260p. 261p. 262p. 263p. 264p. 265p. 266p. 267p. 268p. 269p. 270p. 271p. 272p. 273p. 274p. 275p. 276

Issue Table of ContentsEarly Music, Vol. 34, No. 2 (May, 2006), pp. i-vi+187-356Front Matter [pp. i-258]Editorial [p. 187]Musical Instruments in the Macclesfield Psalter [pp. 189-203]The Renaissance Flute in Mixed Ensembles: Surviving Instruments, Pitches and Performance Practice [pp. 205-223]The Missing Link: The Trombone in Italy in the 17th and 18th Centuries [pp. 225-232]Between Theory and Practice: Comparative Study of Early Music Performances [pp. 233-247]A Josquin Substitution [pp. 249-257]Forqueray "Pieces de Viole" (Paris, 1747): An Enigma of Authorship between Father and Son [pp. 259-276]Performing MattersStaging a Handel Opera [pp. 277-287]

Book ReviewsReview: English Treatises Edited [pp. 289+291-292]Review: The Poetry of Monte's Madrigals [pp. 292-293]Review: Joye for Recorder and Flute Consorts [pp. 293-296]Review: Bach's Protean Passions [pp. 296-298]Review: Ordering Scarlatti's Strange World [pp. 298-301]Review: Unsettling Mozart [pp. 301-302]Review: Beethoven and the Violin [pp. 303-304]

Music ReviewsReview: Trecento Fragments [pp. 305-306]Review: Early Lute Facsimiles [pp. 306-308]Review: Penitential Petrucci [pp. 308-309]Review: Ditties, Psalms and Fa Las [pp. 309-311]Review: For the Home Keyboardist [pp. 311-313]Review: A Viennese Violin Concerto [pp. 313-314]

Recording ReviewsReview: European Renaissance [pp. 317-318]Review: More Iberian Discoveries [pp. 318-324]Review: From Stadtpfeifer to Kapellmeister [pp. 324-326]Review: Varieties of Handel [pp. 327-329]Review: Scandal and Songbirds in the French Baroque [pp. 329-331]Review: Rameau's 'Theatre of Enchantments' on DVD [pp. 331-334]Review: Harpsichord Explorations [pp. 335-337]Review: Haydn and Mozart Sonatas [pp. 337-339]Review: Classical to Romantic [pp. 339-340]

ReportsWilliam Byrd at Duke [pp. 341-342]The Polychoral Tradition [pp. 342-344]Analyzing Baroque Music [pp. 344-345]

CorrespondenceThe Court Suite Revisited: A Brief Response [p. 347]Christmas Pastorellas [pp. 347-349]Temperament in the 19th Century [p. 350]Bach's 'Rosetta Stone' Revisited [p. 350]Blasco de Nebra edition [p. 350]

Abstracts [pp. 351+353]Back Matter [pp. 288-356]