Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

-

Upload

ergoproteo -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

1/8

Studien zurInternational und InterkulturellVergleichenden Erziehungswissenschaft

herausgegeben vonWilfried Bos, Hamburg

Marianne Krger-Potratz, MnsterJrgen Henze, BerlinSabine Hornberg, Bochum

Botho von Kopp, Frankfurt (Main)Knut Schwippert, Hamburg

Dietmar Waterkamp, DresdenPeter J. Weber, Halle (Saale)

Band 3

Waxmann Mnster / New YorkMnchen / Berlin

Hans Dbert, Eckhard Klieme, Wendel in Sroka (eds.)

Conditions of School Performancein Seven Countries

A Quest for Understanding theInternational Variation of PISA Results

Waxmann Mns ter /New YorkMnchen / Berlin

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

2/8

Bibliographie information published by Die Deutsche BibliothekDie Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in theDeutsche Nationalbibliografie; delailled bibliographic da ais available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de.

Findings of the Research Project "Comparison of Education Systems inSelected Countries - Understanding the International Variation of PISAResults", Part I, conducted by a Working Group led by the Gennan Institutefor International Educational Research (DIPF), initiated and financed by theGennan Federal Ministry ofEducation and Research (BMBF).

Studien zu r International und InterkulturellVergleichenden Erziehungswissenschaft, Band 3ISSN 1612-2003ISBN 3-8309-1373-7 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2004Postfach 8603, 0-48046 Mnsterhttp://www.waxmann.comE-Mail: [email protected]: Plemann Kommunikationsdesign, AschebergDruck: Zeitdruck GmbH, MnsterGedruckt auf alterungsbestndigem Papier, DIN 6738Alle Rechte vorbehaltenPrinted in Germany

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

3/8

336 Comparative Study Working Group- measures for further developing and securing quality of tuition and school on the basis ofbinding standards (such as a central Abi/ur) as weil as results-oriented evaluation. the individual school having increased responsibility;measures aimed at opening up the school to its environment and the development of cooperation with neighbours, sports associations. churches. artists. independent maintaining bodiespromoting activities with and by young people. the keywords being partnership. cooperationand dialogue for the nascent educational networks;measures aimed at improving the professionalism of the teaching staff. particularly with regard to diagnostic and methodical competence as a component of systematic school development;measures aimed at strengthening the change of paradigm in teacher in-service training, fromthe qualification of he single teacher to their q ualification in teams and in the school. as weilas to a close-to-reality teacher pre-service training being an important momentum of he necessary educational offensive.a whole. aseries of recent developments. which could take the form of a long-term and efreform and innovation strategy. are emerging. Among them are. in particular: the ten

fed mainly from the new Lnder to flexible institutional solutions within the schoolwhich have been in existence up until now (for example double-tracked secondarythe step-by-step enforcement of a new contra I of the school system by limiting centraland extending the sphere of responsibility of he individual school. the emphasisquality of school and instruction as the core of school development. the change of paradigmthe contra I of he school system towards an output-oriented contra I as weil as the introducof a system of system monitoring and of quality assurance.

Assessments/evaluations (Isabell van Ackeren, Klaus Klemm)following chapter outlines the methods of external examination practised in Germany:continuous assessment and System Monitoring. To understand theseit is necessary to bear in mind the peculiarities of he German school system. whichsystem of cooperative federalism (see seetion 2.1).

External evaluation in Germany: CentraJ examinations, continuous assessment andSystem Monitoringdifferences in school systems between the Lnder. the evident inadequacies of he Germanand the increasing autonomy of ndividual schools throughout Germany have allto the increasing emphasis placed on external evaluation since the mid 90s: centralexaminations for a11 school-Ieavers. standardised tests during the school career and i n t e r ~ Large Scale A ssessments.con/ras/ing models: centralised and decentralisedfinal examinations

of he Lnder use a traditional model of external assessment in the form of centralexaminations. In seven Lnder. there are not only detailed syllabuses. course-book tests,prescriptions, teacher training in assessment, requirements for puttinginto the next class, and the school inspection, as control measures. Even the KM!(for "standards for the middle school final examination" and for "standardised exrequirements" are not deemed sumcient by these Lnder to ensure quality of schooland the equivalence of certificates. They therefore also have central examinationsare taken in Baden-Wrttemberg, Bavaria,and in all the Lnder in the former East Germany, apart from Brandenburg. They diffrom Land to Land and exist for the end of the lower secondary level as weil as for thetable 6).

Germany 337The tradition of central examinations in the three old Lnder goes back to the influence ofthe o c c u ~ y i n g allied forces at the end of World War 11. particularly of France. The French missionary attitude to education was noticeable in Saarland and what was later called BadenWrttemberg. In Rhineland-Palatinate. a central Abitur was introduced during the French occupation. but abolished a few years later. Tbe central final examinations in Bavaria reflect thetraditionally more centralised structure of he Land as a whole. Tbe new Lnder created at reunification in 1990 also had a long tradition of central examinations in the centrally managedUnitary Education System in the GOR. This tradition was carried on in all new Lnder. exceptBrandenburg. But even there. the tendency towards increasing independence of individualschools. together with the need to test and compare school results in connection with the debateabout quality have led to the decision to introduce central examinations for the school year2005/2006 at the latest. Reacting to the PISA results. Lower Saxony also announced that itwould introduce standardised examinations allowing for some freedom for individual schools.

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

4/8

338

CI)Q.

o.t:Ucn>-.aco"a!.a'--8:i....c

Comparative Study Working GroupcQ)cn.o

C'f .r!'-CI)'b.e: ~ : ! : : : .ca eil cu.r!.r!CI)Cl) CI)

co ...+ + .+ + + ic(I).r!(I)- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - ~ C)

on+ + g+ + .+ . [ ~ . s ! ~ 'be:

lXl

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - J2c(I) G .!!!.E+ + + ~ ~ CI) ~ ~

(I)C mEe: :;(1) ~ . a .a E on NI!?+ + + + + ~ . g go

o (I)

i:!.fj'2

coEc o ~ ~ . ! ! I I e S 5o..c::.cu uguI3c: .5u u ...N eIJ n g+ .-

ca "C= .. C ~ : g C '- cuQ) c iC) 'be:.5fI)co; ;cac'e=I)CiCICCCI)ocDCI):c

:caCI) cCI) :0'b i;'e: CDlXlCl) c.8(I) E

"OQ)ca E

(1).,8 c.!Z c 0+ + + + + cg ~ ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - I - - - - - - - - - - - : : J c C i ~ .r!cu.,CI) a.+ +'+ + I + cn"ficuc::eil.!!!eil ::J-51 i i 1 l E ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - 00 E .- _- g j ! g ~ c ~ ~ .g-5

e'o+ +

.... (I):; .!!!~ . r ! ::J- l?1 "fi- a. !!lU ::J cuCI) &

Q):;

:i

Q):;cu"Cc::(I)CI)

Q)(I) :;- .r!::J 0-5 J!!!!l E(I) cua::

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

5/8

Comparative Study Working Groupreform. The examinations -whether centralised or decentralised- have, upnow, primarily been used to provide school-leavers with a recognised qualification. Thereyet been any systematic feedback or use of previous results in schools, although the exin all Lnder are statistically drawn up and evaluated. Access to the data -exvia short press statements- has, up until now, been reduced or prohibited by the ministries,reference to data proteetion laws.

standardised tests during the course 0/ he school careerof he last few years have shown that results fall short ofstandard, results are not equivalent in the whole nation and results are not evaluatedare inadequaeies both in the German education system and in the indischools. Appropriate educational policies are being worked on to redeem this situation.

of eentralised final examinations, control methods are bewill directly affect daily schoollife and so support the individual school.intended, in turn, to help achieve equivalence on a Lnder, anational and an internaThese measures are known as parallel and comparative work.el work' involves comparing students ofparallel classes within one school;ientation work' involves comparing different schools within a de-

work being done by several parallel classes in core subjects (parand Maths) in various school years at primary and secondary levelto Land). Tbe tasks are conceived jointly by the teachers of the parallelat particular time intervals. The ministry provides example tasks asfor difficulty level and assessment criteria. The discussion of parallel work, designednable comparison of individual class results and assessments, reflects a basic debate: the efto achieve objectivity and equivalence, especially given the tendency towards public achas been started in manY Lnder through assessment withinParallel work is being established as a norm-orientated motor for quality evaluation and

It is well known that staff have difficulty establishing equivalent results and asfunction of parallel work is therefore (eg, ForthausIRhrestablish and fix what is to be leamed;encourage discussion between teachers of parallel classes about teaching methods and theircompare not only student achievement, but also staff evaluation methods andencourage discussion within the school, but also between neighbouring schools, for exam-about didactics. known as 'sampie tasks' or 'task pools') have been devised for parallelexample tasks for comparative work will follow. Tbeir function is:clarify requirements set out in guidelines and syllabuses andaid classroom diagnosis other than assessment.has similar aims to parallel work. It has come to the centre of interest in thePISA study. The Standing Conference of Ministers of

of the Lnder of the FRG (KMK) has spoken in favour of imng "orientation and comparative work", cross-nationally and within individual Lnder,to be devised to take place during the course of theto those which exist for the final examinations (Resolutions of May andSo comparative work involves the comparison of several orschools in the Land. Comparative work and parallel work are carried out during a school caand the diagnosis made is not a basis for negative selection mechanisrns, but rather, a bafor better student support. As with parallel work, the comparisons are intended to be imple-

Germany 341mented in the whole Land, both in primary and secondary schools. There are no plans as yet togather background information about the individual schools to help evaluate discrepancies inachievement. It is also unclear whether the results will be centrally gathered and perhaps published and whether they will contribute to the students' grades. Here, further developments anddecisions are awaited.There has been very little research in Germany so far regarding parallel and comparativework. The available literature diseusses the organisational structures stilliargely at the planningstage (eg, KempfertlRolff, 2000). It links these to the educational policies behind them and addresses the first results to have appeared. Tbe discussions are predominantly normative and donot have an academic basis. Tbus, little is known about the effects of these control measures.Parallel and comparative tasks are a sign of he change from an emphasis on eontext faetors toan intensified and systematised emphasis on process and effect of schooling, based on empirical comparative research (see Helmke, 2000 on this paradigm shift). This is also apparent in theintroduction of national comparative studies in the Lnder, which complement the SystemMonitoring of nternationallarge-scale assessments. This is the subject of he next section.

System Monitoring: International and national Large Scale AssessmentsA type of comparative assessment of chosen year groups, either the whole population or a representative sampIe, carried out irregularly in the course of their educational path, came toprominence in Germany in the 1990s. These studies are intended to provide general knowledgeabout educational processes and it is also hoped that they will be useful for the individualschool. Tbe second point particularly applies to the studies carried out within Germany.This type of external evaluation has three forms:- international-scale studies with German participation;- cross-national studies within Germany;- comparative assessment within one Land.The two tabular overviews shown here refer to these three forms. Table 7 gives a chronologicaloverview ofGermany's participation in international comparative studies since the 19605. Table 8 refers to cross-national and single Lllnder studies within Germany. The following sectionwill deal firstly with the important international Large Scale Assessments with German participation and their effects for the development of the German education system. Secondly, thecomparative assessments introduced within Germany will be outlined with examples (for fur-ther information, see van Ackeren/Klemm, 2000, BoslSchwippert, 2002, Weinert, 2001).Participation in the TIMS study marked an important tuming point in the development ofthe German education system. Germany's results, in all types of school, all subject arcas and allLnder, were so mediocre in comparison with other countries, that they incited a debate, stillongoing and now greatly intensified after PISA, about the competence ofthe German educationsystem. One consequence of this debate was that the hitherto widespread scepticism in Germany regarding such large-scale comparative studies was quickly abandoned and even practically reversed. Although there had already been an international comparative study with German participation- the "Intemational Study of Reading Literacy" in the 90s- the debate aboutTIMSS and its effects on Germany shows that TIMSS marked a tuming-point in Germany'sinvolvement with Large Scale Assessments. It was only after the TIMS studies had awakenedinterest in the achievement of German students that belated attention was paid to the international Study ofReading Literacy. This delay in awareness is also surely connected with the factthat public interest in the results of comparative studies was inseparable from the debate aboutGermany's economic situation. In this context, mathematical and scientific literacy evidentlyseemed to the public to be more important than reading literacy and reading habits. This hasmarkedly changed since the PISA study has shown the fundamental importance of reading literacy for other subject areas. The trend towards mediocrity wh ich was confirmed by the international reading study and by TlMSS, has been re-confirmed by PISA. Indeed, Germany's

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

6/8

Comparative Study Working Groupis continuing. Large-scale, interna

of intensive research by educaof education policy makers in Germany since the 1990s,

in the first maths study FIMS and thewas nonetheless absent from most of the international com990s (van Ackeren, 2002). Bos and Postlethwaite see a possible expla

in the 1970s and 1980s in the idea that "German pedagogy isp. 253).

of he German education system in the last few decades, it isand financed.As a consequence of the so-called TIMSS shock and with the aim of overcoming the "black

nt ofvar ious factors and their complexto exof

to the results (van AckerenIRolff 2002). It isof drawing up general reports of results; rather, the data are in

an orientation to help improve their teaching.of hese studies are particularly important:ects of leaming contexts (and of learning development)" (LAU), conducted in

Sill , 7111 , 9111 and lId! Years as a comprehensive longitudinal section. So far,1998 and 2000 for German, Maths and First Foreign Language. It

of attitudes towards leaming and teaching, the study of family back999; Lehmann el al. 2002).ty Studyof School Mathematics Lessons" (QuaSUM), Brandenburg, 1999, which

of grades five and nine in Maths. This study used a repretionnaires about school- and leaming-related atti

el

ost recent of the three studies, the "General Maths Enquiry in Rhineland-Palatinate:of ayear (8d! Year) in a non-city Land. This was carried out in May 2000 and

It used questionnaires for students, teachers and heads of2002).

in need of extensive research. For the projects

found in Peek 2001.

- ...z:: 0ca"CC:cIJI:g Eu 0o_

c CI.. c:a:: :J.!. Co caliI:: C

.:. c:UR':! ,.o(1) ..

lE8

8S80 0 0NN N

cuwo

1ssiSE.....0"iJecri,u)

Nt')0000NN

8N

c.. E& ~ i l -! f; : (1)

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

7/8

Comparative Study Working Groupofthe Monitoring: Weak points ofGerman schools

of the literacy study in the early 1990s (Lehmann, 1995) were initially widelyin Germany with the exception a small group of experts, a fierce debate about

of the German education system was launched when the TIMS-II and TIMS-ill studleswas carried out publicly, by education policy makers, school pro

s, education researchers and didactics experts. It gained new momentum from the reof the international PISA study, presented in 2001, and the evaluation of PISA within

of previous conclusions, carried particular weight througb thempetency of German students in maths, science and reading literacy at the end of their

of upper secondary level are far behind those of then student achievement is apparent both among the stronger and among the

it contradicted the astaugbt in homogenous learning groups. The fmding did not, however, trigger of f a broad

and disadvantages ofthe German school slructure.he-board school achievement below average, but the difference in

is greater in Germany than in any otherween the attainment of competencies and social background is stronger in

in any other country. Tbe German PISA publication (Baumert et al., 2001) reas an effect of assigning students at an early age to educational paths of different

aluation of the school achievement of young people from migrant backgrounds indiamigrant population comparable to Ger

, German schools encourage students from migrant backgrounds less successfully thanan interna I analysis of

of individual Lnder in the areas tested. Tbe most successful Land is, in interof the top third of the participating countries; the gap

is alanning, given the commitment made in the Basic Law (Grundgesetz)living standards within the Federal Republic.

by the achievernent studies carried out in individual Fedare particularly important:sophyof the tracked school system, the decisions about transition fromof secondary school only partly reflect student ability, if

ic competency is insufficient for a reliable recommendation to a parof school. This inadequacy is connected with the fact that prirnary school recom

of ability level between students in different types of secondary school.ows that there is only a sligbt learning curve in schools at

of thc lower secondary level evidently serve toof school, and not so

Germany 345Tbe German school system has no evident advantages to counteract the weak points revealedby the Large Scale Assessments of the last ten years. In the course of the education policy debate, which brougbt this problem to the public's attention, this has had considerable consequences:- Tbe debate incited the introduction of national quality evaluation programmes for the school

system, in nearly all Lnder.- Tbe debate, together with the Federation-Lnder-Commission for Educational Planning and

Research Funding (BLK), and the Standing Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK), caused the committees responsible for the coordination of educationalpolicy across Lnder boundaries to initiate national development programmes to improveschool quality. Tbe most important refonns in these programmes were and are aimed atchanging instructions.

- Tbe debate gave an unprecedented boost to empirically orientated school research, whichmost notably led to the support programmes ofthe German Research Community (DFG).

- Tbe debate led to the KM K's resolution that Germany must participate in future internationalLarge Scale Assessrnents. Another consequence was that several Lnder carried out land-wide achievement tests. Tbe tables here show how broad the spectrum of such tests has be-corne within a short time (see also section 2.7.2).

- Finally, the difference between the PISA results of different Lnder,caused the KMK to initiate the development of national standards of achievement; to be regularly controlled (seechapter 2.3.2). Tbe shock caused by the discrepancy in achievement between Lnder causedthe revival of an earlier discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of cultural federalism -at least in the run-up to the parliamentary election in the summer and autumn of 2002.

Tbe initial attempts to improve quality in German schools, which have been briefly describedhere, do not yet add up to a coherent whole. This is partly because the education policy debateis still ongoing, but also partly because the cornplicated consensus mechanisms of the federaleducation system make unified responses to universally recognised problems difficult, if notimpossible.

-

8/2/2019 Estudio Comparativo Aleman Otras Naciones

8/8

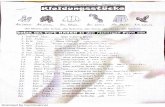

!abJe 8: Lame Scale Asseuments wlthln Germany tuntll 2002)Bezeichnung der Studie Koordlnatlonl Zeitraum Inhalte Alters- Schul- Anzahl bete". Erhebungaart

(alphabetische wlss. Begleitung PlanOrdnung) '" '9 Erhebung Ergab- fKhIlcho Hintergrund gruppe form SchOler Lnder ~ ~ . n n d nian Lelatungen morlunal. ...- ......c lind PI)'CIIOIOL.2 EntwIc*JunQ'1:1 ImJugenclaJIeIDi111 OoutscII-E/IgIIdI-Sc:nIilor-g ~ I n I : o m a D O N l ~ e ~ G r u n d t d I u I ~ : ! O ~ ~ ( f r J r ' 2 ~ J -3 l'rogrImme fIlr lntem&tIOtIIIC SlUdcIUAIMSI/NnI.! ! ! ~

AapckIe 4e t Lomaut-gang.. und 4etL e m e n ~ M a I h e m & l i l t ~ m l A N 1 l l b l i n g

C KompolONen.2 U/lt8llldlllmCllIIUnaIt.U) MQncMerHauptlC:t\lll" S I I I d M I ( t 1 t ~ r I I r i 0- EnvItwtlllllflt SludyJc:i LongdudiMlSllldiozur Geneao'1:1 1ncIivtduIIII8rKo/l'llJOlCllZeni (LOGIK)~ L ~ e l l o 1 o und ~ D O n T'llInton.lntatIISScft und Kompotenzen(SCHotASTlI()

BIJU

DESI

IGLU-E

PISA-E

BIIT

Fond-Unterauchungon

LAU

IlARKUS

ProJoktvorbundMnChnerStudien

QuaSUIl

1991 93 95 0cuIac;h. Engi.. P I ~ 1991 Beginn I.B. Semn..MPIB Borlit 1989 97.2000 laufenc MIllI 8101.. AIpoIde. Moa- mit 7. Klassen alle 1. KohOIte: MV. {wor1lOm_ .. . _. 1-- __. . __________ J . : P r \ y I i k . . . . . . . : . . : . ~ __ II_tIOn....;....;...:..UIIIentChl________ .___ - I ~ --=:ca::,. . . : . : ' 0 : : : : . 0 : : : o o : : . . . . : . N ! ! : R ~ W ! ! :SA::!..!:::1 ..!!IIl....I2!!_:!!!IL.,_-IaystCm . Il1o 10

OIPF 1998 2003 und2004 kIaIIOnIPU- 11 a-tl. JOwei/s ca. ;.lncSIvId. foIeIIunalI 9. Klassen .... 11.000 f\lr EngbdI (UttgI- u. ~ . , 'tIlIIOo$:uctio Inl VgI.... ......__ ._ . - - f . - ' - - - - - ~ = = - - - - - - " ... - ' --- -------"...-....,..---:.....-.-I!o lIlBcr ..BIancI8tlII Univel$itBI H a m b u ~ 1999 2001 L-..sI4nd =.00 nIa. MllIIIom.. FIlIlzojtpIlvil. Ende 4.Klassen Grundschule 8.600 MV. NalulwlU. UntonidIl . NicCorI..

- - - - - ~ - - _ . - _. _ ._ - - - - ..- - - - - - - - - - - ........ .._--- - ---_ '- SA _..-MPIPF MOnchorSlaatsinslltu1 fOSchulp8dagogik uneBildungsfolSchuns

Zentrum fOBIldungsforschunsUniv. KollltaNAmt 10r SchuloHumboldtUniv

1998

1998._ ...1969und1962

200020032006SOlt 1998bzw.2ooorvgolm/lig

1973.1976lowio1977.1979

2004(eISte nil.MlIIIII Ptwo) NauIMIu.

jedes MIIlhemIlIk.Schuqah 0euISdI

n a t . ~ : z.B. zu (1UIIa)- EndeS I alle 50.000 alle CIlUt Ek'IftOIMn .7. K1. (Malllo.. HluptWl.J; - .. , - ~ werden nicht 8. K1. (DeutlCll ." Sdwtt.. Gym.Malh.CrIIObcn 9. K1. (.IIo.uBetH.uptKlt.J 33.000 a.m .-------Wfiile,n-.. ---

Haa.an.20.000 HRW. HIcIOot

. 9 10.lCZlIIe Umwelt Klassen alk-----------+DeIItadt-----=~ = = = - - - - - - - - - - , - I I o - o I \ - I \ - N ..- - - - ~ - - - . -

1996.98. 1997 , ....... Mali'le I ~ . 1 d I u I l I u . 5 7 9 . 11. SoncIOf jeweils ca. .. ......_1995Borllr 2000.2002 ,...., En. EinlleIIungon.lOZ. K1,Non schule' 12.000 ._.-. (Leng____________ ~ - - - - . - - - - _ - - - - - - - - - _ + - - - - - - - ~ H ~ 6 ~ ~ ~ ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - " + _ - - - - - - - - - - - - ______ ~ ~ ~ n ~ m ~ 1 1 = 8. J(Jassen '::; 44.000ildungsmlnlsl.Univiversita 1998 2000 Ende 200( /rrIalIIcm&tikl