Análisis arqueométrico de la cerámica dorada andalusí de ...

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales ...

Transcript of Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales ...

Materiales de ConstrucciónVol. 62, 305, 79-98enero-marzo 2012ISSN: 0465-2746

eISSN: 1988-3226doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materialescerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine

(Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramicmaterials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

M. Setti(*), A. Lanfranchi(*), G. Cultrone(**), L. Marinoni(*)

Recepción/Received: 23-IX-10Aceptación/Accepted: 10-I-11Publicado online/Online publishing: 14-VII-11

RESUMEN

Se ha llevado a cabo un estudio arqueométrico de losmateriales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de San-ta Maria del Carmine en Pavía (Italia). Se han obtenidovaliosas informaciones sobre las temperaturas de coc-ción, la procedencia de las materias primas arcillosas y eltipo de hornos utilizados. Mineralógicamente, las cerámi-cas utilizadas en la iglesia son ricas en cuarzo, feldespa-to y filosilicatos y en algunas muestras se han detectadosilicatos de calcio de neoformación. Las observacionesmicrotexturales han revelado la presencia de incipientesbordes de reacción, la sinterización de los filosilicatos yla parcial vitrificación de la matriz. Las cerámicas poseenuna porosidad elevada (del 32 al 45%) y radio de poroscomprendido entre 0,4 y 1,3 mm. El estudio de los dife-rentes tipos de deterioro muestreados en la fachada dela iglesia (pátinas verdes y negras y eflorescencias) harevelado la presencia de yeso, whewellita, thenardita emoolooita.

Palabras clave: cerámica, petrografía, distribución detamaño de poro, deterioro.

SUMMARY

We performed an archaeometric study of the ceramicmaterials from the façade of the church of Santa Mariadel Carmine in Pavia (Italy). We obtained usefulinformation about the firing temperatures, theprovenance of raw materials and the type of oven used.The ceramics used in the façade are mineralogically richin quartz, feldspar and phyllosilicates, and newly formedcalcium silicate phases were detected in some samples.Microtextural observations revealed the presence ofincipient reaction rims, phyllosilicate sintering and partialvitrification of the matrix. Ceramics show high porosity(32 to 45%) and pore sizes of between 0.4 and 1.3 µm.Our study of the different types of decay collected on thefaçade of the church (green and black patinas andefflorescences) revealed the presence of gypsum,whewellite, thenardite and moolooite.

Keywords: ceramic, petrography, pore size distribution,decay.

(*) Università degli Studi di Pavia (Pavia, Italia). (**) Universidad de Granada (Granada, España).

Persona de contacto/Corresponding author: [email protected]

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 79

1. INTRODUCCIÓN

En este trabajo se describe el estudio analítico de losmateriales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de SantaMaria del Carmine, famoso monumento medieval dePavía (Italia) (Figura 1). Con finalidad arqueométrica sehan investigado las características composicionales y pro-piedades físicas de las cerámicas, con el objetivo de ave-riguar la procedencia de las materias primas arcillosasy establecer las temperaturas de cocción a las que sesometieron las piezas crudas así como el tipo de hornoutilizado. Este tipo de investigación es de suma importan-cia en los procesos de conservación porque los edificioshistóricos deberían ser restaurados utilizando materialescon propiedades similares a los originales. Si se utilizaranmateriales diferentes de los originales se podría compro-meter la durabilidad del monumento (1-5).

Los análisis mineralógicos y texturales de las cerámicasson fundamentales para estudiar los procesos de coccióny determinar la procedencia de las materias primas, queen muchos casos están relacionadas con las litologíasaflorantes en las proximidades del edificio (5-11).

La porosidad y distribución del tamaño de poros son otrosparámetros importantes en predecir la durabilidad de losmateriales de construcción sometidos a ataques agresivoscomo los causados por la lluvia ácida, la cristalización desales y las heladas (1, 4, 12, 13). En efecto, el volumen delos poros y la distribución de los mismos en el seno de unmaterial determinan la capacidad de acumular fluidos y laposibilidad de que estos puedan circular, favoreciendo sudeterioro. Además, variaciones en los valores de porosi-dad de un manufacto cerámico (debido a la composición,temperatura de cocción y posible deterioro) condicionanmarcadamente su resistencia mecánica.

Otro propósito de este trabajo ha sido el de llevar a cabouna comparación entre los resultados petrofíficos de lascerámicas de la iglesia y los datos bibliográficos demonumentos construidos con materiales similares y pro-cedentes de áreas cercanas a Pavía.

80 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

1. INTRODUCTION

In this work we describe the analytical investigation ofceramic materials from the façade of the Church of SantaMaria del Carmine, a famous mediaeval monument inPavia (Italy) (Figure 1). To the archaeometric purposewe studied the compositional characteristics and physicalproperties of the ceramics in order to discover theprovenance of the clayey raw materials and establish thetemperatures at which the green ceramic bodies werefired and the type of oven used. This type of research isof paramount importance for conservation purposes,because historical buildings should be restored usingmaterials with similar properties to the original materials.If materials of different properties are used, this couldcompromise the durability of the monument (1-5).

Mineralogical and textural analyses of the ceramicsprovide an insight into the firing processes and enable usto determine the provenance of the raw materials, whichin many cases came from the outcrops in the vicinity ofthe building (5-11).

Porosity and pore-size distribution are other importantparameters for predicting the durability of buildingmaterials subject to aggressive attacks by acid rain, saltcrystallization and freeze-thaw cycles (1, 4, 12, 13). Infact, the pore volume and the pore size distribution of amaterial determine its fluid storage capacity and the rateat which fluids flow through it, both factors that enhanceits decay. In addition, variations in the porosity values ofa ceramic product (due to its composition, firing andpossible deterioration) have marked effects on itsmechanical resistance.

Another purpose of this study was to compare thepetrophysical results for the ceramics from the church andthe bibliographic data for monuments built with similarmaterials from areas around Pavia.

Figura 1. Fachada de la iglesia. Los círculos blancos indican las áreas donde se han recogido las muestras.Figure 1. Façade of the church. White circles indicate the areas where samples were collected.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 80

1.1. Historia de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine

La iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine está ubicada en elcentro histórico de Pavía, en el norte de Italia, y está con-siderada como uno de los mejores ejemplos de arquitec-tura gótico-lombarda. Este monumento fue comisionadopor la Orden de los Carmelitas (14) y comenzó a construir-se en el año 1374 por Gian Galeazzo Visconti, duque deMilán, sobre la base de un proyecto atribuido a Bernardoda Venezia. La construcción sufrió varias interrupcionespero se mantuvo su planta original en forma de cruz egip-cia (o cruz en forma de Tau), de acuerdo con la icnogra-fía del siglo XIV, y finalmente fue acabada con la realiza-ción de la fachada y el pavimentado interno en 1490 (15).

Al igual que la mayoría de las iglesias de Pavía, la de San-ta Maria del Carmine muestra el ábside orientado hacia eleste y la fachada hacia el oeste, de manera que esta últi-ma queda totalmente iluminada durante el atardecer.

La fachada es de ladrillos macizos unidos entre sí por del-gadas capas de morteros de cal. La fachada es románica yla parte central, que corresponde a la nave central, es con-siderablemente más alta respecto a las dos naves laterales.

La fachada está dividida en cinco sectores verticales porseis imponentes contrafuertes que van reduciendo sutamaño hasta convertirse en pináculos al alcanzar latechumbre. Un séptimo pináculo está colocado en medioa la máxima altura de la fachada, contribuyendo al apa-rente ímpetu ascendiente de la misma.

La iglesia posee una entrada por cada una de las tresnaves. Por encima de las portadas hay cuatro grandesbíforas. La fachada está dominada por un gran rosetónembellecido por un marco de terracota minuciosamentelabrado. En este marco se disponen veintiún rostros depequeños ángeles, colocados en medio de sus alas.

Cuando miramos la iglesia quedamos impresionados por elintenso y brillante color rojo de los ladrillos. De hecho, losladrillos representaban el único material de construccióndisponible en aquel tiempo en los alrededores de Pavía. Enlos años, y después de diversos intentos fallidos, se habíaalcanzado una técnica de elaboración y cocción que eracapaz de conferir un aspecto homogéneo, compacto y lúci-do. Esta técnica, que puede observarse en la fachada de laiglesia, era conocida con el nombre “di parata”, porque seasemejaba a la elegancia de la gente “en el desfile”.

Según Gianani (15), la Orden de los Carmelitas fabricólos ladrillos y terracotas de la iglesia en hornos locales,probablemente en uno antiguo y renovado, del siglo V d.C.y localizado a pocos kilómetros al sur de Pavía.

81Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

1.1. History of the church of Santa Maria del Carmine

The church of Santa Maria del Carmine is located in thehistoric center of Pavia, in northern Italy, and isconsidered as one of the best examples of Lombard-Gothic architecture. This monument was commissionedby the Carmelite Order (14) and was commenced in1374 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the Duke of Milan, basedon a project attributed to Bernardo da Venezia. Althoughconstruction was interrupted on several occasions, theoriginal Egyptian-cross plan (or Tau cross) wasmaintained, according to the 14th century ichnography,and was finally finished with the completion of thefaçade and the internal paving in 1490 (15).

Like most churches in Pavia, in Santa Maria del Carminethe apse faces east and the facade west, which meansthat the latter is lit up by the sunset.

The façade is made of bricks that are joined together bythin layers of lime mortar. The façade is typicalRomanesque with the central part, corresponding to thenave, considerably higher than the two aisles.

The façade is divided into five vertical parts by six largebuttresses, which become more slender as they gethigher and are topped by pinnacles on the roof. Aseventh pinnacle is located in the middle at the highestpoint on the façade, so contributing to its apparentupward impetus.

The church has one entrance for each of the threenaves. Over the doorways there are four large mullionedwindows. The façade is dominated by a great rose-window embellished by a meticulously carved terracottaframe. Inside the frame there are twenty-one faces ofangels, which are framed by their wings.

Those who observe the church are impressed by theintense, bright red colour of the bricks. Bricks were infact the only building materials available in the Paviaarea at that time. Over the years, and after several failedattempts, a manufacturing and firing technique wasdeveloped which resulted in a homogeneous, compactand bright appearance. This technique, which can beobserved on the façade of the church, was known as “diparata”, because it echoed the smart appearance ofpeople “on parade”.

According to Gianani (15), the Carmelite Ordermanufactured the bricks and the terracotta for thechurch in local kilns, most likely in an old, renowned kilnthat dated back to the 5th Century A.D. and was locateda few kilometres south of Pavia.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 81

2. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS

Los materiales cerámicos han sido muestreados en lafachada durante un reciente trabajo de restauración dela iglesia. El muestreo se ha llevado a cabo teniendo encuenta los siguientes tipos de materiales y su grado dedeterioro (Figura 1):

• ladrillos;• ángeles alrededor del rosetón;• marco por debajo de los ángeles;• molduras cerca de los pináculos;• terracotas sobre las portadas;• productos de deterioro en la fachada.

Teniendo en cuenta la importancia del monumento ypara ocasionar el menor daño posible, ha sido posiblemuestrear solo un reducido número de muestras (dieci-nueve) y de pequeño tamaño.

Las muestras, excepto los productos de deterioro, hansido divididas en tres grupos en base a la tipología y suubicación en la fachada:

Grupo A: muestras E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7, E8, E9, E10,E11, E13, E20 y E23. Han sido recogidas de los elemen-tos decorativos del rosetón (ángeles y marco).

Grupo B: muestras E16, E17 y E18. Provienen de losladrillos.

Grupo C: muestras E14, E22 y E24. Provienen de otroselementos decorativos de la fachada (sobre la portadade la derecha y cerca del pináculo de la izquierda).

El color de la mayoría de las muestras, determinado porcomparación con las fichas del Sistema Munsell de Color(16), era marrón claro YR 5/6.

El estudio mineralógico de las diecinueve muestras se hallevado a cabo utilizando un difractómetro de rayos X(DRX) Philips PW 1800 con radiación de emisión CuKα(50 kV, 30 mA) y una velocidad de goniómetro de 1º2θ/min. El análisis semicuantitativo de las fases minera-les se ha efectuado utilizando los poderes reflectantes decada fase determinados experimentalmente, de acuerdocon los métodos propuestos por Culliti (17) y RodríguezGallego et al. (18).

Para la determinación de los elementos mayoritarios, seha efectuado un análisis por fluorescencia de rayos X(FRX, S4 Pioneer, Bruker AXS). Únicamente dos mues-tras (E4 y E23) fueron utilizadas para este análisis ya queeran las únicas con una cantidad de material suficiente(aproximadamente 5 g).

82 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ceramic samples were collected from the façade duringa recent restoration of the church. Sampling wasperformed considering the following types of materialsand their degree of decay (Figure 1):

• bricks;• angels from around the rose-window;• frame below the angels;• moulding near the pinnacles;• terracotta above the doorways;• decay products on the façade.

In view of the importance of the monument and in orderto cause as little damage as possible, only a very limitednumber (nineteen) of small samples were collected.

Samples, except the decay products, were divided intothree groups on the basis of their typology and theirlocation on the façade:

Group A: samples E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7, E8, E9, E10, E11,E13, E20 and E23. Collected from decorative elementsfrom the great rose-window (angels and frame).

Group B: samples E16, E17 and E18. From bricks.

Group C: samples E14, E22 and E24. Taken from otherdecorative elements on the façade (above the rightdoorway and near the left pinnacle).

The colour of most of the samples, determined bycomparison with Munsell Colour System charts (16), wasLight Brown YR 5/6.

Mineralogical study of nineteen samples were carried outusing a Philips PW 1800 X ray diffractometer (XRD) withCuKα emission radiation (50 kV, 30 mA) and agoniometer rate of 1° 2θ/min. Semiquantitative analysisof mineral phases was performed using experimentallydetermined reflectance power of each phase, accordingto the methods proposed by Culliti (17) and RodríguezGallego et al. (18).

X ray fluorescence (XRF, S4 Pioneer, Bruker AXS)analysis was carried out to determine the majorconstituent elements. Only two samples (E4 and E23)were used for this analysis, because they were the onlyones with sufficient amounts of material (about 5 g).

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 82

La textura y microtextura de las muestras ha sido deter-minada por medio de las microscopías óptica y electróni-ca. En el primer caso, se ha utilizado un microscopioóptico polarizado (MOP) Olympus BX-60 equipado conuna unidad de microfotografía digital (Olympus DP-10).En el segundo caso, se ha utilizado un microscopio elec-trónico de barrido con emisión de campo (FESEM) LeoGemini 1530 equipado con microanálisis Oxford INCA200. Se han utilizado láminas delgado-pulidas metaliza-das con C.

La distribución de tamaño de los poros y el volumenporoso han sido determinados por porosimetría de intru-sión de mercurio (PIM). Fragmentos de cerámicas deaproximadamente 2 cm3 fueron secados en estufasdurante 24 h a 100 ºC y luego analizados mediante unequipo Micromeritics AutoPore III 9410.

3. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN

3.1. Mineralogía y textura de las cerámicas

La Tabla 1 muestra la composición mineralógica de lascerámicas obtenida por DRX. Las cerámicas están com-puestas por cantidades variables de cuarzo, feldespatosalcalinos, plagioclasa, mica y menores cantidades de anfí-bol, clorita, yeso, diópsido, gehlenita, hematites y calcita.Cabe indicar que el yeso dificulta la correcta identificaciónde la gehlenita porque el pico principal de la gehlenita (a2,85 Å) queda enmascarado por la reflexión (200) delyeso. En todas las muestras se han detectado cantidadessignificativas, pero variables, de fases amorfas.

La MOP ha permitido investigar la textura y composiciónde la matriz así como la naturaleza del degrasante (19).Las cerámicas presentan generalmente una matriz degrano fino en la que destacan los fragmentos de degra-sante por su mayor tamaño. Estos fragmentos estáncompuesto por cuarzo, mica (biotita y moscovita), fel-despatos alcalinos, y en menor medida por plagioclasa yanfíbol (hornblenda). Como degrasante se han utilizadotambién fragmentos de chamota. Las micas mantienen,en algunos casos, su hábito y propiedades ópticas mien-tras que en otros están exfoliadas según los planos basa-les debido a la dexidroxilación (20) y disminuyen subirrefringencia. La calcita aparece únicamente como cris-tales esparíticos y se localizan en los poros de las cerá-micas lo que revela su origen secundario. La matriz secompone de pequeñas láminas de mica, otros silicatos yla componente amorfa que se ha formado durante lacocción. El predominante color rojo de la matriz se debea parte del hierro presente en la materia prima que se hatransformado en hematites durante la cocción. No hasido posible verificar la presencia de diópsido o gehleni-ta (previamente detectados por DRX), debido a sus

83Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

The texture and the microtexture of the samples weredetermined by means of optical and electron microscopy.In the first case, an Olympus BX-60 polarized opticalmicroscope (POM) equipped with a digital microphotograpyunit (Olympus DP-10) was used. In the second case, aLeo Gemini 1530 field emission scanning electronmicroscope (FESEM) equipped with Oxford INCA 200microanalysis was used. Polished thin sections coatedwith C were used.

The distribution of pore sizes and the pore volume weredetermined by mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP).Ceramic chips of about 2 cm3 were oven-dried for 24 hat 100 °C and subsequently analyzed using a MicromeriticsAutoPore III 9410 apparatus.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Mineralogy and texture of ceramics

Table 1 shows the mineralogical composition of theceramics obtained by means of XRD. The ceramics arecomposed of variable amounts of quartz, alkali feldspars,plagioclase, mica and lesser amounts of amphibole,chlorite, gypsum, diopside, gehlenite, hematite andcalcite. It is important to point out that gypsum hindersthe correct identification of gehlenite, because the mainpeak for gehlenite (at 2.85 Å) is masked by the (200)reflection of gypsum. Significant, albeit varying, amountsof amorphous phases were detected in all the samples.

POM enabled us to investigate the texture andcomposition of the matrix as well as the nature of thetemper (19). Ceramics generally show a fine-grain matrixin which grains of temper stand out because they arelarger. These grains are made up of quartz, mica (biotiteand muscovite), alkali feldspar and, at a subordinatelevel, plagioclase and amphibole (hornblende). Chamottefragments were also used as temper. In some casesmicas maintain their shape and their optical properties,while in others they appear exfoliated along basal planesdue to dehydroxilation (20) and their birefringence falls.Calcite only appears in the form of sparitic crystalslocated in the pores of the ceramics, so revealing itssecondary origin. The matrix is composed of small micalaminas, other silicates and the amorphous componentformed during firing. The predominant red colour of thematrix is due to the fact that part of the iron in the rawmaterial is transformed into hematite during firing. Itwas impossible to verify the presence of diopside orgehlenite (previously detected by XRD), because theparticles were too small. Reaction rims have developedon some of the silicate grains. These help us to

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 83

dimensiones muy pequeñas. Algunos de los granos desilicatos muestran el desarrollo de bordes de reacciónque ayudan a determinar el grado de cocción de lasmuestras. Las cerámicas son composicional y textural-mente bastante homogéneas aunque pueden observarsealgunas diferencias en la distribución del tamaño de par-tículas, porosidad y proporción matriz/degrasante entreladrillos y terracotas. En general, la porosidad, evaluadamediante MOP, está comprendida entre 10 y 30%, eldegrasante entre 20 y 30% y que la matriz representa el40-60% de las muestras. Los granos del degrasante sue-len mostrar una clasificación de moderada a buena.

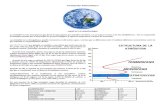

En cuanto a los análisis de FRX, las dos muestras (E4 yE23) representadas en el diagrama ACS (Al2O3-CaO-SiO2, Figura 2) se encuentran en el campo pobre en cal-cio (20), siendo la muestra E23 un poco más rica en CaO

84 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

determine the degree of firing of the samples. Ceramicsare compositionally and texturally rather homogeneous,even if some differences can be observed between bricksand terracotta in terms of particle size distributions,porosity and matrix/temper ratio. In general, theporosity, measured using POM, accounts for between 10and 30%, the temper between 20 and 30%, and thematrix makes up 40-60% of the samples. The grains ofthe temper usually show moderate-to-good sorting.

As regards XRF analyses, the two samples (E4 and E23)plotted in the ACS diagram (Al2O3-CaO-SiO2, Figure 2)fall within the calcium-poor field (20) with sample E23being slightly richer in CaO than E4. CaO content is less

Figura 2. Imágenes al microscopio óptico (Nícoles paralelos) de las muestras cerámicas que pertenecen a los Grupos A (imágenes a y b), B (imágenes c y d) y C (imágenes e y f). a) muestra E6 con una matriz rojiza homogénea; b) relictos de cristales de mica en la

muestra E8; c) granos de pequeño tamaño en la matriz de la muestra E16; d) presencia de una capa superficial oscura (barniz) en la muestra E17; e) textura homogénea en la muestra E24; f) cristales de mica orientados en la muestra E24.

Figure 2. Optical microscopy images (parallel Nicols) of ceramic samples from Groups A (images a and b), B (images c and d) and C (images e and f). a) sample E6 with homogeneous reddish matrix; b) relicts of mica crystals in sample E8; c) small grains

of the matrix in sample E16; d) presence of a superficial dark layer (varnish) on sample E17; e) homogeneous texture in sample E24;f) oriented mica crystals in sample E24.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 84

que E4. El contenido en CaO es menor del 9% y una par-te es de origen secundaria. Los análisis por DRX y MOPhan puesto de manifiesto que estas dos muestras contie-nen yeso, y en la muestra E23 se aprecian también tra-zas de calcita. Si extrapolamos los resultados de FRX atodas las muestras estudiadas, se puede sugerir que lasmaterias primas utilizadas en la producción de las cerámi-cas contenían bajas cantidades de carbonatos. En efecto,la relativa escasez de estos minerales en las materias pri-mas explica porque se ha desarrollado una cantidad muybaja de silicatos de calcio (diópsido y gehlenita) durantela cocción.

3.2. Descripción de las temperaturas decocción y diferencias entre los grupos de cerámicas

En cuanto al origen de los minerales identificados porDRX (Tabla 1), cuarzo, feldespato alcalino, clorita, anfí-bol y mica son constituyentes primarios de la materia pri-ma arcillosa (21-23), mientras que diópsido, gehlenita,hematites y fases amorfas proceden de las transforma-ciones que tuvieron lugar durante la cocción de las cerá-micas (9, 11, 21, 24-27). La mineralogía ha proporcio-nado informaciones útiles sobre las temperaturas decocción. Los minerales arcillosos que estaban presentesen la masa original se transformaron durante la cocción,

85Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

than 9% and part of it is of secondary origin. XRD andPOM analyses highlighted that these two samplescontain gypsum, and in sample E23 traces of calcitewere also detected. If we extrapolate the XRF results toall the samples, it appears that the raw materials used toproduce ceramics had a low carbonate content. In fact,the relative scarcity of these minerals in the rawmaterials explains why only very small amounts ofcalcium silicates (diopside and gehlenite) were producedduring firing.

3.2. Description of firing temperatures anddifferences between the groups of ceramics

As regards the origin of the minerals identified by XRD(Table 1), quartz, alkali-feldspar, chlorite, amphibole andmica are primary constituents of the clayey raw material(21-23), while diopside, gehlenite, hematite andamorphous phases were produced by the transformationswhich took place during firing (9, 11, 21, 24-27). Themineralogy has provided useful information on the firingtemperatures. Clay minerals present in the original pastewere completely transformed by the firing, because theyare unstable at temperatures of over 500-550 °C (28).

(*) trazas / traces, * escaso / scarce, ** abundante / abundant, *** muy abundante / very abundant.

Chl clorita /chlorite

Gp yeso /

gypsum

M mica /mica

Qz cuarzo /quartz

Afs feldespatoalcalino /

alkali-feldspar

Pl plagioclasa /plagioclase

Cal calcita /calcite

Didiópsido /diopside

Ghgehlenita /gehlenite

Ampanfíbol /

amphibole

Hemhematites /hematite

Amamorfo /

amorphous

A

E1 (*) ** *** ** * ** --- --- --- (*) * **

E2 --- --- (*) *** ** (*) --- --- * --- * ***

E4 * (*) ** ** * * --- (*) * (*) (*) ***

E5 --- * ** ** *** * --- --- --- (*) (*) **

E6 --- (*) ** ** * * --- --- * (*) * ***

E7 * --- ** ** ** ** --- --- --- * (*) **

E8 --- --- ** ** ** * --- * --- * (*) **

E9 --- --- ** *** ** * --- * --- * * ***

E10 --- --- ** ** * * --- --- --- (*) * ***

E11 --- --- ** ** * *** --- * --- * (*) **

E13 --- (*) *** *** ** * (*) --- --- (*) (*) *

E20 * (*) ** ** ** ** --- --- --- (*) (*) **

E23 ** * ** ** (*) (*) ** --- (*) (*) (*) **

B

E16 --- --- ** ** ** * --- * --- * * ***

E17 --- (*) * ** * * --- --- --- (*) * ***

E18 --- * * ** ** (*) --- * --- (*) * ***

C

E14 --- ** ** ** (*) (*) (*) --- --- --- ** ***

E22 --- * * ** * (*) (*) ** * --- * ***

E24 --- (*) ** ** * * (*) * --- --- (*) ***

Tabla 1 / Table 1Análisis semicuantitativo por DRX de las muestras cerámicas que están divididas en los Grupos A, B y C definidos en el texto.

XRD semiquantitative analysis of ceramic samples which are divided into Groups A, B and C as defined in the text.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 85

porque son inestables a temperaturas por encima de500-550 ºC (28). La mica empieza a reducir su birrefrin-gencia y desaparece a temperaturas superiores a los900 ºC (29). Dado que este mineral está siempre pre-sente en las diecinueve muestras estudiadas, ninguna delas piezas fue cocida por encima de esta temperatura. Lapresencia de gehlenita sugiere que las cerámicas fueroncocidas a temperaturas mayores de 800 ºC porque estesilicato de aluminio empieza a aparecer por encima delos 900 ºC de acuerdo con la reacción: metakaolín + cal-cita � gehlenita. El diópsido aparece alrededor de los850 ºC y es estable a temperaturas por encima de 1000 ºC(24). La asociación de diópsido y gehlenita más micaindica que el intervalo de temperaturas de cocción denuestras cerámicas estaba comprendido entre 800 y900 ºC y que nunca se alcanzaron los 1000 ºC. Final-mente, dado que la calcita, dependiendo de su tamañode grano y del área específica superficial, generalmentedesaparece en torno a los 800 ºC (30), y teniendo encuenta la morfología encontrada en nuestras muestraspor MOP, este mineral es un producto de precipitaciónde los morteros adyacentes.

Los estudios por DRX y MOP han permitido diferenciarlos tres grupos de cerámicas (A, B y C) en base a lassiguientes observaciones:

Grupo A: este grupo incluye los ángeles y el marco alre-dedor del rosetón. Se caracteriza por una textura bastan-te homogénea con abundante matriz de color rojizo ytamaño medio-fino. La porosidad alcanza el 20%. Eldegrasante está moderadamente clasificado y compues-to por cuarzo, feldespato alcalino, mica y menores canti-dades de plagioclasa y hornblenda. Granos de grandesdimensiones son bastantes raros. Los bordes de granovarían de angular a subangular (Figura 3a). Las láminasde micas están uniformemente distribuidas en la matriz(Figura 3b) donde se observan pequeños cristales deotros silicatos, así como pequeñas manchas rojizashomogéneamente distribuidas que indican la presenciade óxidos-hidróxidos de Fe.

Grupo B: el grupo B incluye los ladrillos de la fachada.Difieren de las cerámicas del grupo anterior por unmayor contenido en degrasante que está bien clasificadocon bordes subangulares y compuesto principalmentepor cuarzo, feldespato alcalino, mica y poca hornblenda(Figura 3c). Los granos de silicatos muestran bordes dereacción y las láminas de mica aparecen uniformementedistribuidas. La matriz es fuertemente rojiza y compues-ta por pequeños cristales de mica, silicatos y hematites.La porosidad varía entre el 15 y el 30%. El alto conteni-do en degrasante indica una diferente producción, dadoque estos tipos de materiales no fueron elaborados conpropósitos decorativos. El mayor contenido en diópsido yfases amorfas y menor contenido en mica respecto a las

86 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

The birefringence of mica begins to fall and the micadisappears completely at temperatures of over 900 °C(29). As this mineral is present in all nineteen samples,this means that none of the pieces were fired attemperatures above this mark. The presence of gehlenitesuggests that the ceramics were fired at temperatureshigher than 800 °C, because this aluminium silicatebegins to appear above 900 °C following the reaction:metakaolin + calcite � gehlenite. Diopside appearsaround 850 °C and it is stable at temperatures of over1000 °C (24). The combined presence of diopside,gehlenite and micas indicates that the range of firingtemperatures of our ceramics was between 800° and900 °C and never reached 1000 °C. Finally, as calcite,depending on its grain size and specific surface area,usually disappears at around 800 °C (30), and taking intoaccount the morphology observed in our samples byPOM, this mineral is a product of precipitation fromadjacent lime mortars.

XRD and POM investigations allowed us to differentiatebetween the three groups of ceramic (A, B and C) on thebasis of the following observations:

Group A: This group includes the angels and the framearound the big rose-window. It is characterized by arather homogeneous texture with abundant, reddish,medium-fine matrix. Porosity reaches 20%. The temperis moderately sorted and made up of quartz, alkalifeldspar, mica and lesser amounts of plagioclase andhornblende. Large grains are very rare. The edges of thegrains vary from angular to sub-angular (Figure 3a).Mica laminas are randomly distributed in the matrix(Figure 3b) where small crystals of other silicates arepresent, as well as small, homogeneously dispersed,reddish spots which indicate the presence of Fe oxide-hydroxides.

Group B: Group B includes the bricks from the façade.They differ from the ceramics in the previous groupbecause they have a higher temper content, which iswell sorted with sub-angular edges and mostly made upof quartz, alkali-feldspar, mica and a little hornblende(Figure 3c). The silicate grains show reaction rims andmica laminas appear randomly distributed. The matrixhas a strong red colour and is made up of small crystalsof mica, silicates and hematite. Porosity varies between15 and 30%. The higher temper content indicates adifferent manufacturing process, as these types ofmaterials were not moulded for decoration purposes.The higher diopside and amorphous-phase content andthe lower mica content compared to samples from Group

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 86

muestras del Grupo A, sugiere que la materia prima delGrupo B fue cocida a temperaturas más altas. La mues-tra E17 es particularmente interesante porque contieneuna capa superficial de barniz rojo. Esta capa, rica enóxidos de hierro, penetró de manera discontinua en elladrillo y fue probablemente aplicada para conferir unacoloración roja más intensa a la pieza (Figura 3d).

Grupo C: este grupo incluye elementos decorativos pareci-dos a los del Grupo A. Se caracterizan por tener una textu-ra muy homogénea y fina en la cual la matriz (65-80%) esmucho más abundante que el degrasante (Figura 3e). Adiferencia del Grupo A, la matriz es más fina y los granos

87Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

A, suggests that the raw material used in Group Bsamples was fired at higher temperatures. Sample E17 isparticularly interesting as it contains a superficial layer ofred varnish. This layer, rich in iron oxides, penetratedinside the brick discontinuously and was probablyapplied to give the piece a more intense, red colour(Figure 3d).

Group C: This group includes decorative elements similarto those in Group A. They are characterized by a veryhomogeneous and fine texture in which the amount ofmatrix (65-80%) is much higher than that of temper(Figure 3e). Unlike Group A, the matrix is finer and the

Figura 3. Imágenes al FESEM de las muestras cerámicas que pertenecen a los Grupos A (imágenes a y b), B (imágenes c y d) y C(imágenes e y f). a) muestra E9 con baja sinterización de la matriz; b) fragmento de chamota en la muestra E7; c) incipiente sinterización

en la muestra E18; d) imagen detallada de la muestra anterior con un relicto de pintura sobre la superficie; e) fragmento de terracotabien preservada (muestra E22) con alto un grado de sinterización; f) sales sobre la superficie de la muestra E22 y espectro EDS.

Figure 3. FESEM images of ceramic samples from Groups A (images a and b), B (images c and d) and C (images e and f). a) sampleE9 with low sintering of the matrix; b) fragment of chamotte in sample E7; c) incipient sintering in sample E18; d) detailed image of

the previous sample with a relict of paint on the surface; e) fragment of well preserved terracotta (sample E22) with high degree of sintering; f) salts on the surface of sample E22 and EDS spectrum.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 87

de degrasante son generalmente de tamaño más pequeño.En la matriz se pueden también observar pequeños crista-les de mica orientados (Figura 3f). La porosidad varía entreel 10 y el 30%. Teniendo en cuenta la mineralogía, la tem-peratura de cocción parece ser un poco más baja de lasmuestras del Grupo B y similar a las del Grupo A.

Debido a su homogeneidad, parece que las materias pri-mas utilizadas para fabricar las cerámicas fueron prepara-das con esmero. Se ha observado también que las cerá-micas utilizadas para los elementos decorativos (Grupos Ay C) fueron preparadas con materias primas más seleccio-nadas que las utilizadas para los ladrillos del Grupo B.

Dos muestras, E2 y E23, parecen algo diferentes de lasdemás. La muestra E2, que es un fragmento de ángel,se caracteriza por una textura heterogénea, con unamatriz parcialmente amorfa, de color rojo y degrasantemal clasificado compuesto por granos de dimensionesmayores que los de todos los otros elementos decorati-vos. Suponemos que este ángel sea una sustitución deuna pieza original. La muestra E23, que es un fragmen-to de terracota, destaca por su elevado grado de dete-rioro y presenta el más alto contenido en calcita de ori-gen secundario.

3.3. Estudio microtextural de las cerámicas

Las observaciones al FESEM han permitido investigardiferentes aspectos microtexturales de las cerámicascomo el tamaño y forma de los poros, el grado de sinte-rización, la presencia de bordes de reacción y de puen-tes intergranulares (31).

Grupo A: Las cerámicas de este grupo muestran una tex-tura bastante homogénea. Los cristales tienen morfolo-gías angulares o subangulares y no se observan bordesde reacción (Figura 4a). La porosidad intergranular eselevada y el grado de sinterización es bajo. Estos datosindican una temperatura de cocción relativamente baja.Las observaciones al FESEM han permitido identificarademás fragmentos de chamota añadidos a la materiaprima como degrasante (Figura 4b).

Grupo B: Los materiales cerámicos de este grupo mues-tran una textura bastante homogénea. Ocasionalmentese han observado puentes intergranulares que indicanuna incipiente sinterización (Figura 4c). Los bordes degranos son generalmente subangulares o redondeados.

En la superficie de la muestra E18 se ha reconocido un relic-to, de 20-30 µm de grosor, de un originario nivel de barnizparecido al de la muestra E17 (Figura 4d). Suponemos queesta pintura fue aplicada sobre la superficie de los ladrillosantes de su cocción, para obtener una superficie lisa y pararesaltar la intensidad del color rojo.

88 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

grains of temper are generally lower in size. Small,oriented mica crystals can be seen in the matrix (Figure3f). Porosity varies between 10 and 30%. On the basisof the mineralogy, the firing temperature would seem tohave been a little lower than the samples in Group B andsimilar to those in Group A.

The homogeneous nature of the raw materials used tomould the ceramics suggests that they were preparedwith care. We also noted that the ceramics used fordecorative elements (Groups A and C) were preparedwith more selected raw materials than those used for thebricks in Group B.

Two samples, E2 and E23, have a strikingly differentappearance from the others. Sample E2, which is afragment of an angel, has a heterogeneous texture, withan amorphous, red matrix and a scarcely sorted tempermade up of grains that are larger than those found in allthe other decorative elements. We therefore supposethat this angel is a replacement of the original piece.Sample E23, which is a fragment of terracotta, standsout for its strong degree of decay and has the highestamount of calcite of secondary origin.

3.3. Microtextural study of ceramics

We used FESEM observation to investigate variousmicrostructural aspects of the ceramics, such as the sizeand shape of the pores, the degree of sintering, thepresence of reaction rims and intergranular bridges (31).

Group A: The ceramics in this group had a ratherhomogeneous texture. The crystals are angular or sub-angular in shape and no reaction rims are observed(Figure 4a). Intergranular porosity is high and there is alow degree of sintering. These features indicate arelatively low firing temperature. FESEM observation alsoallowed us to identify chamotte fragments added to theraw materials as temper (Figure 4b).

Group B: Ceramic materials from this group show arather homogeneous texture. Intergranular bridges,indicating incipient sintering, are sometimes observed(Figure 4c). The grain rims are generally subangular orrounded.

The remains of an original layer of varnish, 20-30 µmthick, can be seen on the surface of sample E18 which issimilar to that of sample E17 (Figure 4d). We imaginethat the paint was applied to the surface of the bricksbefore they were fired, in order to obtain a smoothsurface and enhance the intense, red colour.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 88

Grupo C: Las muestras de este grupo presentan una tex-tura muy homogénea. Los bordes de granos tienen for-ma subangular y están frecuentemente conectados porpuentes intergranulares. El grado de sinterización esgeneralmente bastante alto (Figura 4e). En particular, enla muestra E22 no ha sido posible obtener fórmulas este-quiométricas exactas de las fases minerales porque hansufrido, parcial o totalmente, sinterización.

En el borde de la muestra E22 se observa una capa de yesoasí como sugiere el microanálisis (Figura 4f y espectro EDS).

89Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

Group C: Samples from this group have a veryhomogeneous texture. The edges of the grains aresubangular and frequently connected by intergranularbridges. There is a generally high degree of sintering(Figure 4e). In particular, in sample E22 it wasimpossible to obtain precise stoichiometric formulas formineral phases because they had been either totally orpartially sintered.

A layer of gypsum is observed on the edge of sampleE22, as suggested by microanalysis (Figure 4f and EDXspectrum).

Figura 4. Curvas de distribución de tamaño de poro por PIM de las muestras cerámicas. Volumen intruido (en mL/g) versus radio de poro (en mm).

Figure 4. MIP Pore size distribution curves for ceramic samples. Intruded volume (in mL/g) versus pore radius (in mm).

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E24

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E20

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E7

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E5

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E2

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E1

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E18

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

r (μm)0.001 0.01 0.1 1 10 100

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

E10

Log

DV

/DR

(m

L/g)

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 89

3.4. Caracterización del sistema poroso

Los análisis de PIM se han llevado a cabo sobre ochomuestras seleccionadas en base a las diferentes tipolo-gías de cerámica, el grado de deterioro y la composiciónpetrográfica. Los resultados se presentan en la Tabla 2.Se trata de materiales bastante porosos ya que se llegaa alcanzar el 45% de porosidad como en el caso de lamuestra E1. Los valores de densidad real son caracterís-ticos de estos tipos de materiales ricos en silicatos. Ladiferencia entre densidad real y aparente es generalmen-te más alta cuanto más porosas son las cerámicas. Lascurvas de distribución de tamaño de poro de las mues-tras son mayoritariamente unimodales con un pico prin-cipal en torno a 1 mm (Figura 5). Las cerámicas con ele-vada porosidad (E1, E5, E7 y E10) muestran los valoresmás altos de superficie específica (SSA, Tabla 2), mien-tras las de baja porosidad (E2 y E18), tienen valoresrelativamente más bajos. Los valores de superficie espe-cífica aumentan con el incremento de los poros máspequeños que son los más responsables en los procesosde alteración (1, 2). En efecto, los materiales cerámicoscon alta porosidad y alto porcentaje de poros con radiospor debajo de 2,5 mm son más susceptibles de deterio-rarse, especialmente cuando están sometidos a procesosde hielo-deshielo y cristalización de sales (2, 4, 12).Algunas de las cerámicas más alteradas (E1, E5 y E7)muestran altos valores de área específica y bajos valoresde radio de poro, mientras que la muestra en mejor esta-do de conservación, E2, presenta el valor más bajo deporosidad y el pico de la curva porométrica más despla-zado hacia tamaños de poros más altos.

Se suele asumir que la porosidad de un material cerámi-co disminuye al incrementar la temperatura de coccióndebido al aumento de la sinterización (1, 2, 4, 24, 32). Sinembargo, no se trata de una regla general, ya que tam-bién la composición mineralógica condiciona fuertemente

90 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

3.4. Pore system characterization

MIP analysis was carried out on eight samples selectedon the basis of different ceramic typologies, the degreeof decay and petrographic composition. The results arelisted in Table 2. These materials are quite porous asshown by Sample E1, which reaches porosity levels of45%. The real density values are characteristic of thesetypes of material rich in silicates. The difference betweenreal and apparent densities generally increases, themore porous the ceramics are. Pore size distributioncurves for the samples are mostly unimodal with amaximum peak at around 1 mm (Figure 5). Ceramicswith higher porosity (E1, E5, E7 and E10) show higherspecific surface area (SSA, Table 2) values, while thosewith low porosity (E2 and E18) have relatively lowervalues. Specific surface area values increase in line withthe number of smallest pores, which are the mostimportant in decay processes (1, 2). In fact, ceramicmaterials with a high porosity and a high percentage ofpores with radii of less than 2.5 µm are more prone todecay, especially when they are subjected to freeze-thaw and salt crystallization processes (2, 4, 12). Someof the most damaged ceramics (E1, E5 and E7) showhigh specific surface area and low pore radius values,while the best preserved sample, E2, is characterized bythe lowest porosity value and a porometric curve peakthat tends toward higher pore radii.

It is generally assumed that the porosity of a ceramicmaterial decreases as the firing temperature rises, due toincreased sintering (1, 2, 4, 24, 32). However, this is nota general rule, as the mineralogical composition also hasa strong influence on porosity (1, 2, 24). Calcite, in

Tabla 2 / Table 2Parámetros porométricos de los materiales cerámicos que están divididos en Grupos A, B y C definidos en el texto.

Se ha efectuado un análisis porométrico por muestra. Porosimetric parameters of the ceramic materials divided into Groups A, B and C, as defined in the text.

One porometric analysis per sample has been carried out.

SSAárea específica superficial /specific surface area (m2/g)

ρρA

densidad aparente / apparentdensity (g/cm3)

ρρR

densidad real / real density(g/cm3)

Pporosidad abierta / open

porosity (%)

A

E1 16.44 1.45 2.64 45.16

E2 6.08 1.82 2.69 32.10

E5 15.37 1.55 2.63 41.07

E7 18.15 1.49 2.62 43.14

E10 9.97 1.54 2.71 43.37

E20 9.85 1.62 2.58 37.30

B E18 2.36 1.47 2.29 35.68

C E24 14.50 1.49 2.44 38.91

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 90

la porosidad (1, 2, 24). En particular, la calcita favorece unaumento de porosidad ya que a elevadas temperaturas sedescompone liberando CO2, reacciona con los silicatos ysuele dejar espacios vacíos donde estaban presentes losgranos de calcita. Además, cuando los ladrillos están coci-dos a temperaturas comprendidas entre 800 y 1000 ºC,los carbonatos pueden facilitar el desarrollo de fisuras debi-do al fenómeno conocido como “rotura por caliche” (33).Por otra parte, la ausencia de carbonatos en las materiasprimas causa una progresiva reducción de la porosidad dela cerámica, por la coalescencia de los poros pequeños ydisminución de la conexión entre los poros. Dado que lasmaterias primas arcillosas utilizadas para fabricar las cerá-micas de la iglesia poseen un bajo contenido en carbona-tos, la porosidad debe estar directamente relacionada conla temperatura de cocción. De hecho, las muestras cocidasa una temperatura relativamente más baja (E1 y E10)muestran valores de porosidad más altos mientras las coci-das a temperatura más alta (E2, E5, E18 y E20) presentanvalores más bajos (Tabla 2). Finalmente, la porosidad estárelacionada, al menos en parte, con el grado de alteraciónde las muestras de la iglesia (evaluadas mediante obser-vaciones al microscopio). La cerámica más alterada, E1,muestra los valores más altos de porosidad mientras la demejor estado, E2, posee el valor más bajo.

Es interesante la buena comparación entre los valores deporosidad, distribución de tamaño de poro y temperatu-ras de cocción de las muestras estudiadas, y los de ladri-llos de épocas romana y medieval procedentes de otrosmonumentos (1, 34) y también de ladrillos cocidos enlaboratorio a temperaturas comprendidas entre 800 y900 ºC (2); esta similitud podría confirmar la temperatu-ra de cocción de las cerámicas de la iglesia previamentesugerida. La porosimetría de mercurio, así como losestudios mineralógicos y texturales, ha revelado la pre-sencia de muestras anómalas. En particular, E18 es laúnica cerámica con una clara distribución bimodal del

91Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

particular, leads to an increase in porosity because athigh temperatures it decomposes by releasing CO2, itreacts with silicates and usually leaves empty spaceswhere calcite grains were present. Moreover, when thebricks are fired at temperatures of between 800 and1000 °C, carbonates can cause fissures to develop dueto a phenomenon known as “lime blowing” (33).Conversely, the absence of carbonates in the rawmaterials causes a progressive reduction of ceramicporosity, because of the coalescence of small pores anda decrease in pore interconnection. Given that the clayeyraw materials used to produce the ceramics used in thechurch have only low amounts of carbonates, theporosity must be directly related to the firingtemperature. As a matter of fact, the samples fired atrelatively lower temperature (E1 and E10) show highporosity values, while those fired at higher temperature(E2, E5, E18 and E20) show lower values (Table 2).Finally, porosity is related, at least partly, to the degreeof decay of the samples from the church (measuredusing microscopic observations). The most damagedceramic, E1, shows the highest porosity values, while thebest preserved sample, E2, shows the lowest.

It is interesting that the samples we studied show similarresults for porosity, pore size distribution and firingtemperatures as the bricks from Roman and Mediaevalmonuments (1, 34) as well as bricks fired in thelaboratory at temperatures of between 800 and 900 °C(2); this similarity is an additional confirmation of thefiring temperature for the samples from the church,proposed above. Mercury porosimetry, like mineralogicaland textural studies, revealed the presence ofanomalous samples. In particular, E18 is the onlyceramic with clear bimodal distribution of the poreaccess size. The layer of paint detected on its surface

Figura 5. Diagrama ACS (Al2O3–CaO–SiO2) que muestra la composición química de las muestras E4 y E23.Figure 5. ACS (Al2O3–CaO–SiO2) diagram showing the chemical composition of samples E4 and E23.

SiO2

Al2O3

E23E4

100

80

60

40

20

00 20 40 60 80 100

100

80

60

40

20

0

CaO

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 91

tamaño de acceso de poro. La capa de pintura detecta-da en su superficie puede haber modificado la curvaporométrica sellando parte de los poros y disminuido su área superficial (Tabla 2). La muestra E2, que hemosconsiderado una sustitución de un ángel sobre la basedel análisis mineralógico, difiere de las otras muestraspor su valor más bajo de porosidad y la posición del picohacia radios de acceso más altos (1,5 µm). Estos aspec-tos indican que esta muestra fue cocida a elevada tem-peratura, dado que la porosidad suele disminuir mientrasque el tamaño de los poros aumentar por la coalescen-cia de los poros pequeños.

3.5. Procedencia de las materias primas y procesos de manufactura

No es siempre fácil averiguar la procedencia de las mate-rias primas utilizadas en la industria cerámica. Los ladri-llos en la antigüedad han sido producidos utilizandogeneralmente materias primas que se encontraban cer-ca de las obras a construir, por obvias razones de trans-porte y costes (5, 8, 9, 35, 36). No obstante, en algunoscasos los ladrillos procedían de áreas muy lejanas de laubicación del edificio. Por ejemplo en Irlanda los ladrilloseran frecuentemente importados de Gran Bretaña yHolanda y viajaban como lastre de barco (9). Podía tam-bién ocurrir que la geología del área alrededor del edifi-cio mostrara notables variaciones y las materias primaseran, por tanto, diferentes (35). Finalmente, debemostener en cuenta también que los artesanos modificabancon frecuencia la textura originaria y la composiciónmineralógica de las materias primas añadiendo aditivospara mejorar la calidad de las cerámicas.

En este trabajo se ha intentado evaluar la procedencia delas materias primas y el proceso de manufactura compa-rando la composición de los materiales cerámicos con laslitologías aflorantes alrededor de Pavía y con ladrillos deotros monumentos de la ciudad. Entre estos últimos cabecitar las antiguas murallas de defensa de la ciudad de edadRomana y del periodo en el cual la ciudad estuvo goberna-da por los españoles (5), los ladrillos de edad Romana pro-cedente de la Torre Cívica de Pavía (10) y otros materialescerámicos romanos cerca de Pavía (21). La región en losalrededores de Pavía puede ser dividida en dos áreas,Lomellina en el Norte y Oltrepo Pavese en el Sur. En Lome-llina y los campos próximos a Pavía se encuentran suelosarenosos o arenosos-limosos de origen fluvial o fluviogla-ciar, caracterizados por altos contenidos en cuarzo, plagio-clasa y clorita mientras que calcita, dolomita y mineralesarcillosos hinchables están casi ausentes (21, 23). Los sue-los del Oltrepo Pavese son más arcillosos y la composiciónmineralógica difiere de la de Lomellina por la notable pre-sencia de esmectita, calcita y, en algunos casos, de serpen-tinita (21, 22). El Oltrepo Pavese ha sido siempre un áreaimportante para la producción cerámica.

92 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

may have modified the porometric curve by filling part ofthe pores and reduced its surface area (Table 2). SampleE2, which textural analysis suggests is a replacement ofan angel, stands out from the other samples because ithas the lowest porosity value and the peak tends tohigher access radii (1.5 µm). These features indicate thatthis sample was fired at a high temperature, as porosityusually decreases as pore size increases, due to thecoalescence of small pores.

3.5. Provenance of raw materials and manufacturing process

It is not always easy to discover the provenance of theraw materials used in the ceramics industry. Sinceancient times, bricks have generally been producedusing raw materials found close to the building site, forobvious transport and cost reasons (5, 8, 9, 35, 36). Insome cases, however, they were brought from areas along way away from the building. In Ireland for instancebricks were frequently imported from Great Britain andthe Netherlands and travelled as ship’s ballast (9). It wasalso possible that the geology of the area around the siteof building varied a great deal and the raw materialswere therefore different (35). Lastly, we must also takeinto account that the craftsmen frequently altered theoriginal texture and mineralogical composition of the rawmaterials by using additives to improve the quality of theceramics.

In this work we have tried to ascertain the provenance ofthe raw materials and the manufacturing process used bycomparing the composition of the ceramic materials withthe lithologies appearing around Pavia and with bricksused in other monuments in the city. The latter includesthe bricks from the city’s ancient defensive walls, whichdate from both the Roman era and the period in which thecity was ruled by Spain (5), the Roman bricks from theTorre Civica (i.e., Civic Tower) of Pavia (10) and otherRoman ceramic materials from the surrounding area (21).The region around Pavia can be divided into two areas,the Lomellina in the North and the Oltrepo Pavese in theSouth. In the Lomellina area and in the fields close toPavia sandy or sandy-silt soils of fluvial or glaciofluvialorigin predominate. These are characterized by a highcontent of quartz, plagioclase and chlorite, while calcite,dolomite and swelling clay minerals are almost absent (21,23). The Oltrepo Pavese soils are more clayey and theirmineralogical composition differs from those of Lomellina,due to the significant presence of smectite, calcite and, insome cases, serpentinite (21, 22). Oltrepo Pavese hasalways been an important area for ceramic production.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 92

Los análisis mineralógicos y químicos han indicado que elmaterial original utilizado en la producción de las cerámi-cas de la iglesia estudiada contenía pocos carbonatos loque sugiere que la materia prima arcillosa no procede delOltrepo Pavese sino que fue muestreada en las proximi-dades de Pavía.

La composición mineralógica y textural de las cerámicasde la iglesia presenta fuertes similitudes con la de losladrillos de edad romana procedentes de la muralla y dela Torre Cívica de Pavía (5, 10) y de artefactos romanosde los alrededores de Pavía (21). Por otra parte, difierende los ladrillos de la muralla española de Pavía (5), por-que estos últimos tienen alto contenido en calcita prima-ria y están ausentes las fases de neoformación, indican-do que fueron cocidos a temperaturas más bajas (nomás de 750 ºC). Probablemente, durante la “Edad Espa-ñola”, los artesanos añadieron calcita o margas a lasmaterias primas, para conferir colores más claros a lascerámicas y alcanzar la sinterización a temperaturas másbajas (24). Carbonatos de origen primaria no han sidodetectados en las cerámicas de la iglesia de Santa Mariadel Carmine debido a las temperaturas de cocción másaltas. Es, por tanto, interesante observar cómo los arte-sanos que prepararon los ladrillos de la iglesia utilizaronuna manufactura típica de los romanos y no de los espa-ñoles, que gobernaron esta parte de Italia poco despuésde la construcción de la iglesia, en los siglos XVI y XVII.Dado que los materiales estudiados están generalmentebien clasificados, y composicional y texturalmente bas-tante homogéneos, las materias primas utilizadas en laproducción de los ladrillos fueron preparadas con esme-ro. La terracota fue preparada con materias primas aúnmás seleccionadas que las utilizadas para los ladrillos.

En cuanto a las técnicas de cocción, los ladrillos en la anti-güedad venían generalmente cocidos en hornos abiertos,que es el método más antiguo, o en hornos cerrados. El tipode atmosfera de los hornos, oxidante o reductora, dependedel método de cocción y puede ser averiguado estudiandoalgunas características de la cerámica, como, por ejemplo,su color. De acuerdo con Tite (26), Pavia (9) y Pavía yRoundtree (36), en el caso de cocción en un horno cerradolas variaciones de temperatura son limitadas, la cocción eslenta, los valores máximos de cocción están generalmentecomprendidos entre 750 y 950 ºC y la atmosfera es oxidan-te. Por otra parte, las condiciones reductoras son típicas delos hornos abiertos donde las cerámicas están en contactocon el combustible y la atmosfera puede variar, siendoexpuesta a las variaciones meteorológicas. Nuestro materialcerámico está caracterizado por colores rojo y naranja y laconstante presencia de hematites. Estos aspectos indicanuna permanente condición oxidante, típica de una cocciónen horno cerrado. Además, la cocción en horno abierto pue-de inducir la aparición de defectos típicos como el corazónnegro o marcas de reducción (36). Su ausencia en nuestras

93Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

Mineralogical and chemical analyses highlighted that theoriginal raw material used to produce the ceramics of theinvestigated church contained low amount ofcarbonates, which suggests that the clayey raw materialdid not come from Oltrepo Pavese, and was in factquarried near Pavia.

The mineralogical and textural composition of theceramics of the church shows strong similarities withthat of the Roman bricks from the city walls and theTorre Civica (5, 10), and Roman artefacts discoverednear Pavia (21). They are however different from thebricks in the Spanish walls of Pavia (5), because thelatter have a high primary calcite content and no newlyformed phases, which indicates that they were fired atlower temperatures (up to 750 °C). During the “SpanishEra”, the craftsmen probably added calcite or marl to theraw materials, in order to lighten the colour of theceramics and to reach sinterization at lowertemperatures (24). Primary carbonates were notdetected in the ceramics of the church of Santa Maria delCarmine because of the high firing temperatures used. Itis, therefore, interesting to note that the craftsmen thatprepared the bricks for the church used a manufacturingprocess that followed Roman lines and was quitedifferent from that used by the Spanish, who ruled thispart of Italy, in the 16th and 17th centuries, shortly afterthe construction of the church. The fact that thematerials we studied are generally well sorted andcompositionally and texturally quite homogeneousindicates that the raw materials used in brick productionwere prepared with considerable care. The raw materialsused to make terracotta were even more carefullyselected.

As regards firing techniques, bricks in ancient timeswere generally fired in clamps (open fires), the oldestmethod, or in kilns (closed fires). The particularatmosphere of the kiln, either oxidizing or reducing,depended on the method of firing and can beestablished by studying certain characteristics of theceramic, such as its colour. According to Tite (26),Pavia (9) and Pavía & Roundtree (36), in the case ofkiln firing variations in temperature are limited, firingis slow, the maximum firing values are generallybetween 750 and 950 °C and the atmosphere isoxidizing. Conversely, reducing conditions are typicalof clamps, where the ceramics are in contact with fueland the atmosphere can be variable, as a result ofmeteorological changes. Our ceramic material ischaracterized by red and orange colours and theconstant presence of hematite. These featuresindicate a permanent oxidizing condition, typical ofkiln firing. In addition, clamp firing may lead to theappearance of typical defects like black core orreducing marks (36). The fact that our samples have

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 93

muestras sugiere una vez más que las cerámicas fueroncocidas en hornos cerrados.

3.6. Productos de deterioro

Los productos de deterioro identificados en la fachada dela iglesia pertenecen a tres tipologías: pátina verde, páti-na negra (es decir, costra negra) y eflorescencia blanca.La Figura 6 muestra las imágenes al FESEM y los análi-sis EDS y por DRX de estos productos (muestras E15,E19 y E21).

94 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

none of these defects suggests once again that theceramics were fired in a kiln.

3.6. Decay products

Three types of decay product were identified on thefaçade of the church: green patina, black patina (i.e.black crust) and white efflorescence. Figure 6 showsFESEM images and the EDS and XRD analyses of theseproducts (samples E15, E19 and E21).

Figura 6. Imágenes al FESEM de productos de deterioro sobre la fachada de la iglesia. Se muestran los espectros EDS y difractogramasde DRX. a) pátina verde sobre la muestra E15; b) eflorescencia blanca sobre la muestra E19; c) costra negra sobre la muestra E21.

Leyenda: Qz = cuarzo; M = moolooita; Cal = calcita; Gp = yeso; T = thenardita; W = whewellita.Figure 6. FESEM images of decay products on the façade of the church. EDS spectra and XRD diffractograms are shown. a)

green patina on sample E15; b) white efflorescence on sample E19; c) black crust on sample E21. Legend: Qz = quartz; M = moolooite;Cal = calcite; Gp = gypsum; T = thenardite; W = whewellite.

Posición / Position (º2Theta)10 20 30 40 50

2000

1000

0

E15; E15

Posición / Position (º2Theta)10 20 30 40 50

4000

2000

0

E19; E19T

Gp W

M

Qz

Qz

Posición / Position (º2Theta)10 20 30 40 50

1000

500

0

E21; E21

Amorfo / Amorphous

Qz

Cal

200μm

20μm

100μm

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 94

Las pátinas verdes están mayoritariamente compuestaspor moolooita (CuC2O4·nH2O), yeso (CaSO4·2H2O), whe-wellita [Ca(C2O4·H2O)], cuarzo y mica (Figura 6a). El ori-gen de la moolooita, un oxalato de cobre, puede ser atri-buida a la degradación de un original pigmento de cobre.En particular los microanálisis EDS han evidenciado lapresencia de Cu y Cl; esto podría sugerir que el pigmen-to aplicado fuera el “verde Brunswick”, un pigmento ver-de compuesto de cloruro de cobre, que fue utilizado,también como antivegetativo, desde 1800 (37). Otrahipótesis es suponer que los elementos decorativos sobrelos cuales se han encontrado las pátinas verdes fueronpintados con malaquita. Se sabe que este mineral puedealterarse en sulfatos y cloruro de cobre que, a su vez,pueden transformase en moolooita (38). Por tanto, laidentificación de la moolooita no puede ser interpretadacomo un nuevo producto de deterioro sino la transforma-ción de un original elemento de protección (verde Bruns-wick) o decoración (malaquita). La formación de whewe-llita (un oxalato de calcio) está generalmente relacionadacon los procesos de deposición y transformación de mate-ria orgánica disuelta en agua. La materia orgánica puedederivar de los excrementos de animales como ratas opalomas, o de antiguos tratamientos utilizados para pro-teger o embellecer las superficies (39). El yeso se ha for-mado tras la precipitación de fluidos ricos en sulfatos enla superficie de la cerámica. Finalmente, el cuarzo y lamica pueden ser componentes de la cerámica o procederdel polvo acumulado en la superficie.

La eflorescencia blanca está compuesta por thenardita(Na2SO4) más cuarzo y ortoclasa (Figura 6b). La thenar-dita, un mineral muy común en las eflorescencias, se for-ma generalmente tras la circulación de fluidos sobresa-turados en la pared de ladrillos y morteros (40). Lasimágenes al FESEM muestran el desarrollo de cristaleseuhédricos de esta sal. La thenardita causa frecuente-mente daños significativos en las piezas cerámicas por-que se transforma tras el proceso de hidratación en mira-bilita (Na2SO4·10H2O) con un incremento de volumen deaproximadamente el 300%, generando así fuertes presio-nes en las piezas en las cuales cristaliza (40, 41).

Finalmente, los análisis de DRX sobre la costra negra nohan revelado la presencia de fases cristalinas, pero elestudio por FESEM/EDS ha mostrado cantidades impor-tantes de Fe y Pb, elementos relacionados con productosde combustión o con la contaminación producida por laoxidación de canaletas de hierro en la fachada (Figura 6c).Debe recordarse que la fachada de la iglesia se encuentrafrente a una plaza en la cual hasta hace pocos años losvehículos podían circular y aparcar mientras que la ausen-cia de canaletas excluye otros posibles enriquecimientosen Fe y Pb. Parece por tanto ser que los contaminantesprocedentes de los tubos de escape de los vehículos hansido los responsables del desarrollo de las costras negras.

95Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 305, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

Estudio arqueométrico y evaluación del deterioro de los materiales cerámicos de la fachada de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavía, Italia)

Archaeometric investigation and evaluation of the decay of ceramic materials from the church of Santa Maria del Carmine (Pavia, Italy)

Green patinas are mostly made up of moolooite(CuC2O4·nH2O), gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), whewellite(CaC2O4·H2O), quartz and mica (Figure 6a). Moolooite,a copper oxalate, probably results from the decay of anoriginal green copper pigment. In particular, EDSmicroanalyses highlighted the presence of Cu and Cl; thiswould suggest that the pigment applied was “Brunswickgreen”, a green pigment made of copper chloride, thathas also been used as an antifouling agent, since 1800(37). Another hypothesis is that the decorative elementson which the green patinas were found had been paintedwith malachite. It is known that this mineral can convertinto sulphates and copper chloride, which, in turn, cantransform into moolooite (38). Moolooite is therefore theproduct of the transformation of an original protective(Brunswick green) or decorative element (malachite) andcannot be interpreted as a new decay product. Theformation of whewellite (a calcium oxalate) is usuallyrelated to the processes of deposition and transformationof organic matter dissolved in water. This organic mattermay come from the excrements of animals like rats orpigeons, or from products used in the past to protect orembellish surfaces (39). Gypsum was formed by theprecipitation of fluids rich in sulphates on the surface ofthe ceramic. Lastly, quartz and mica may be componentsof the ceramic or may be contained in dust accumulatedon the surface.

The white efflorescence is made up of thenardite(Na2SO4), plus quartz and orthoclase (Figure 6b).Thenardite, a very common mineral in efflorescences,usually forms through the circulation of oversaturatedfluids in brick-and-mortar walls (40). FESEM imagesshow the development of euhedral crystals of this salt.Thenardite frequently causes significant damage toceramic pieces because it is transformed by hydrationinto mirabilite (Na2SO4·10H2O) causing its volume toincrease by about 300%, which exerts strong pressureon the pieces in which it crystallizes (40, 41).

Lastly, XRD analyses on black crust did not reveal thepresence of crystalline phases, but FESEM/EDSinvestigation showed considerable amounts of Fe andPb, elements that are often related to combustionproducts or to the contamination produced by theoxidation of iron drainpipes in the façade (Figure 6c). Itmust be remembered that the façade of the church is ina square in which until a few years ago cars could driveand park while the absence of drainpipes exclude otherpossible Fe and Pb enrichments. It seems likely thereforethose pollutants from vehicle exhausts were responsiblefor the development of black crust.

16545 Materiales, 305 (F).qxp 7/3/12 14:26 Página 95

4. CONCLUSIONES

La manera más adecuada de estudiar las cerámicas anti-guas es efectuando un estudio integrado, usando dife-rentes técnicas analíticas que permitan evitar discrepan-cias en la interpretación de los resultados (6-8).

El estudio de las características composicionales y físicasde los materiales cerámicos procedentes de la fachadade la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine han sido muyútiles para obtener datos sobre su producción. En parti-cular, esta investigación sugiere que la temperatura decocción estuvo comprendida entre 800 y 900 ºC y quelas materias primas procedían de áreas locales (Lomelli-na) que eran pobres en carbonatos. Las materias primasutilizadas para moldear las cerámicas fueron preparadascon esmero, tamizándolas y añadiendo chamota paraincrementar el porcentaje de degrasante. La coccióntuvo lugar en un horno cerrado y atmósfera oxidante.Los elementos decorativos (Grupos A y C) fueron prepa-rados con materias primas más seleccionadas que lasutilizadas para los ladrillos comunes (Grupo B). Debido asu correcta preparación, los materiales cerámicos hanresultado ser homogéneos y caracterizados por un inten-so y brillante color rojo, a veces acentuado por la aplica-ción de barniz rojo. Por primera vez se observa la apli-cación de barnices ricos en óxidos de Fe en la superficie dealgunos ladrillos (por ejemplo los que por algún defectoo por un alto contenido en carbonatos eran de color rojomás claro) para aumentar su tono rojo. Esta técnica,desconocida hasta el momento en otros monumentos,ha sido identificada gracias a los análisis llevados a caboen este estudio y revela el posible secreto de los ladrillos“di parata” de Pavía. Es interesante observar que, engeneral, la producción de la cerámica fue similar a la uti-lizada por los romanos en los alrededores de Pavía. Lascerámicas muestran unos valores de porosidad variables,aunque generalmente altos, que dependen de la tempe-ratura de cocción y del grado de deterioro que han sufri-do. Los análisis han permitido, además, reconocer mues-tras anómalas que representan sustituciones o que hansufrido una fuerte alteración.

Las características de las materias primas y de las condi-ciones de cocción de las cerámicas antiguas, así comolos valores de porosidad deben ser tenidos en cuenta enobras de reparación, sustitución o reconstrucción de losedificios antiguos. En efecto, los materiales cerámicoscon elevada porosidad y alto porcentaje de poros condiámetros por debajo de 2 µm están más sujetos a losprocesos de deterioro. Al contrario, una matriz vítreamejora la resistencia del material al deterioro (3).

Las principales formas de deterioro encontradas en lascerámicas de la iglesia de Santa Maria del Carmine hansido las pátinas verdes, las eflorescencias blancas y las

96 Mater. Construcc., Vol. 62, 79-98, enero-marzo 2012. ISSN: 0465-2746. doi: 10.3989/mc.2011.62310

M. Setti et al.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The best way to investigate ancient ceramics is to adoptan integrated approach using different analyticaltechniques, as this helps to avoid discrepancies in theinterpretation of results (6-8).