Ensayo Relato Fundamental - Guevara

-

Upload

dante-peralta -

Category

Documents

-

view

22 -

download

5

description

Transcript of Ensayo Relato Fundamental - Guevara

Índice INTRODUCCIÓN 5

ENSAYO FUNDAMENTAL 9

Conflictos con la expresión “relatador” 10 Conflictos con la expresión “linguocentrismo” 10 Cuestiones Conceptuales 11

RELATO Y NARRACIÓN 15

LISTADO DE HERRAMIENTAS 16

LA MUERTE DE LA LENGUA 47

La "mitad más valiosa" 48 La cuestión del envío 50 El soporte “fetiche” 53 La cuestión de la palabra 54 La cuestión multimedia 55 Superposición de funciones 57 Fin de la era lingual 59

RELATADOR-PERSONA 61

Relatador-Persona 64 Sistema Perceptivo 64 Órganos de Percepción 65 Órganos de actuación 66 Órganos de interacción 66 Competencias 67 Mundo 68 LAPs: Licencias, Acuerdos, y Permisos 68 Moralejas 70

3

English version 75

INTRODUCTION 75

FUNDAMENTAL ESSAY 81

On the expression “relator”: some conflicting points 82 On the expression “linguocentrism”: some conflicting points 83 Some conceptual issues 83

RELATION AND NARRATION 87

LIST OF TOOLS 88

THE DEATH OF THE TONGUE 121

The “most valuable” half 122 The question of the sending 124 The “fetish” support 127 The word question 128 The multimedia question 129 Overlapping of functions 131 The end of the lingual era 133

RELATOR-PERSONA 135

Relator-persona 138 Perceptive system 138 Organs of perception 139 Performance organs 140 Organs of interaction 140 Competences 141 Genetic and knowledge codes 141 World 142 LAPs: Licenses, agreements and permissions 142 Moral 144

4

Ensayo Fundamental

Introducción Estos son algunos de los interrogantes que he intentado resolver con lo que le ofrezco:

Una persona dice una frase cargada de ironía a su suegra. Al mismo tiempo, otra, en otra parte del globo, dice textualmente lo mismo. Ambas suegras dan idénticas respuestas. Luego, ellas y otros millo-nes ríen viendo una comedia de televisión que pone al descubierto su poca originalidad. ¿Quién debe cobrar los derechos si todos crea-ron las líneas al decirlas? ¿Cada vez que alguien sintió la necesidad de expresar la frase, habló por sí o fue “poseído” por alguien más? ¿Acaso la cultura? ¿La genética? ¿Las hormonas? ¿La Warner Brothers? ¿Todos juntos? ¿Ninguno de ellos?

Un candidato replica el mismo mensaje de texto a todos los electo-res. Algunos reciben una caricia y se disponen a votarlo, otros un insulto que refuerza su decisión de no hacerlo. ¿Podemos decir que se replicó un “mismo” mensaje solo porque todos portaron las mis-mas letras? ¿Parte del contenido o del texto estaba fuera del mensa-je? ¿Qué clase de cosa es un mensaje? ¿Y un texto?

5

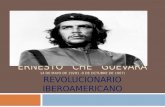

Alejandro Guevara

Un médico ciego ingresa a la habitación de un paciente, transcurre unos minutos en el más absoluto silencio y, cuando se retira, hace un diagnóstico más preciso que el de sus colegas videntes. Le pre-guntamos cómo lo hizo y nos explica que la familia narró con elo-cuencia. Pero ¿quién lo hizo si no hubo palabras? ¿Acaso los olores narran? ¿O las respiraciones? ¿O tal vez hay "lenguaje" en las tem-peraturas del ambiente o de los cuerpos? ¿Cómo pudo haber narra-ción sin palabras? ¿Había un "contenido" en esa habitación? ¿O es-taba en la cabeza del médico? ¿O en ambos lados? ¿Pudo haber un relato? ¿Entonces, qué clase de cosa es un relato?

Vemos la versión en español latinoamericano de Los Simpson y a muchos nos parece aún mejor que la original en inglés. Luego, los mismos doblajistas nos ofrecen una deslucida versión de otra pelí-cula al punto que preferimos verla con subtítulos. ¿Acaso los acto-res perdieron su talento? ¿Es responsabilidad de los directores? La versión española europea nos resulta menos graciosa. ¿Donde están las diferencias si el video es el mismo? ¿Es la dirección? ¿El etno-centrismo de alguna cultura? ¿Son las reglamentaciones para audio-visuales? ¿Son todos juntos? ¿Un video, con diferente audio, sigue siendo el mismo? Pero entonces, ¿quién es el narrador? ¿Qué clase de cosa es? ¿Son muchas personas en un mismo ente? ¿Y la narra-ción visual? ¿Responde también a un texto? ¿Existe texto sin sin-taxis?

¿Qué ha cambiado si, cuando volvemos a ver una película, vemos cosas que no vimos la primera vez? ¿Acaso no es el mismo tape? ¿El mismo guión? ¿Los mismos ojos? ¿Diversas personas ven lo mismo en un cuadro, en un afiche o en una película? ¿Una canción, diez años después, es la misma canción? ¿Y un libro cien años des-pués?

Una minuciosa descripción del rostro congelado de una persona frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, ¿es una historia? En la foto de un rostro, ¿hay una narración? ¿Cuál es el papel del tiempo en una foto?

6

Ensayo Fundamental

¿Y en una historia? ¿Es el que pasó antes? ¿Es el que pasó después? ¿Es el que transcurre a los que la ven? ¿No hay tiempo? ¿Es rele-vante la medición del tiempo para definir qué clase de cosa sea un relato? ¿O solo discrimina tipos de contenido?

Alguien narra una situación en la que otra persona tuvo miedo y lo hace con voz trémula pero no quiere expresar su propio temor sino el del aludido. ¿La voz o la palabra, además de decir, muestran? El narrador habla ahora tal como lo hizo un personaje pero no cambia su actitud inmediatamente sino que funde las voces de narrador y personaje durante unos segundos, ¿es por un momento dos personas a la vez mientras hace una transición similar al fundido entre tomas de video? Ahora, la narradora parada frente a cientos de estudiantes da a su discurso una cadencia identificable como “canto escolar”, ¿es ella la que habla o es el “rol” de la maestra que se adueña de su aparato fonador? Un uniformado esdrujuliza y eso confiere un matiz imperativo a su discurso, el matiz no lo expresa a él sino a la insti-tución a la que representa. Un locutor calvo habla en off de las bon-dades de un champú desenredante, es la voz de la experiencia pero no de la suya sino la de los guionistas del departamento de marke-ting aun cuando también carezcan de cabello.

Dos personas leen el mismo libro. Una de ellas descubre en el texto el verdadero sentido de la vida. La otra no recuerda lo que leyó pero sí que le aburrió. ¿Ambos observaron la misma cosa? ¿Si no contac-taron con lo mismo por qué le llamamos igual? Al tiempo la prime-ra de ellas descubre que fue engañada por el libro y la segunda al re-leerlo encuentra el verdadero sentido de la vida. ¿Cuáles son las propiedades del texto? ¿Entre sus propiedades está cambiar las vi-das de las personas? ¿No tiene ninguna propiedad? ¿Sus propieda-des cambian con el tiempo? ¿Puede decirse de un libro que jamás fue leído, que es un libro? ¿Y de unas palabras que jamás fueron di-chas? ¿Puede un escrito a la vez ser una narración y no serlo? ¿Qué clase de cosa es una narración?

7

Alejandro Guevara

El libro contenedor del "verdadero sentido de la vida" se pierde. Su único adepto, antes de morir, compra un espacio en un medio de comunicación y difunde esa verdad al mundo. Pero lo pone al aire fuera del prime time. Y, peor aún, a esa misma hora el planeta está viendo jugar al Barcelona. No logra un solo espectador, luego, se pierde el verdadero sentido de la vida. ¿De quién fue culpa? ¿Del li-bro? ¿De los medios de comunicación? ¿De la “cultura de masas”? ¿Del deporte? ¿De Lio Messi? ¿Cuál es el verdadero sentido de la vida?

Como verá, son muchas preguntas sin resolver.

Preguntas que la adolescencia global reeditó, exponiendo la ende-blez de las viejas creencias sobre la manera en que relatamos, que es la manera en que seremos. La descarga de música por internet crea multimillonarias disputas sobre qué es un autor y cuáles sus dere-chos, que involucran cuestiones legislativas, filosóficas, sociológi-cas y políticas además de económicas. Por otro lado, la tecnología en los celulares colocó a la mano de millones, dispositivos de edi-ción y captura de audio, video y texto con recursos para “organizar” (editar) la realidad, exponiendo la discrecionalidad que hemos teni-do para diseñar nuestra propia existencia. Y el muro que supo haber entre “vida real” y “ficción” ha sido corroído por los reality shows, que expusieron la “guerra fría” entre instituciones que se proclama-ban “autorizadas” a decidir quiénes somos o debemos ser.

Es el momento, entonces (como que es la llave de la libertad mis-ma), de revisar los fenómenos que intervienen en la búsqueda, ofre-cimiento y creación de sentido.

8

Ensayo Fundamental

Ensayo Fundamental El Ensayo Fundamental sobre el Relato está integrado por tres tra-bajos a modo de tríada: La Muerte de la Lengua, Relato y Narra-ción y Relatador-Persona. Individualmente, son abordajes sobre diferentes aspectos de la cuestión del relato y, en conjunto, una des-cripción exhaustiva del fenómeno. Puede revisar sólo el aspecto que le resulte interesante y, si quiere ampliar, encontrará en los otros alusiones a los mismos temas desde diferentes ángulos.

En La Muerte de la Lengua, ensayo una denuncia de lo que llamo linguocentrismo, un modo de colocar el foco sobre el mundo (y construirlo) auspiciado por el mismo complejo de inferioridad que impulsa al sexismo o el racismo.

En Relato y Narración, le ofrezco diez herramientas esenciales pa-ra ofrecedores de contenidos: narradores, escritores, actores, inte-grantes de producciones de medios audiovisuales, profesores, pinto-res, cantantes, arquitectos… y, en diferentes circunstancias, todos los humanos.

9

Alejandro Guevara

En Relatador-Persona, propongo un modelo del modo en que aco-piamos experiencias y saberes celebrando relatos.

Conflictos con la expresión “relatador”

El uso de “relatador”, ha generado desconcierto por el cambio de paradigma, que propone que quienes relatan no son quienes creía-mos hasta ahora (los que narran, por ejemplo) sino quienes, con las ofertas de otras personas o de su propia curiosidad, celebran relatos “en” ellos mismos.

No se trata de una elección equívoca sino de un conflicto buscado para provocarle a desestructurar el viejo modo de relatar que llamo “linguocéntrico”.

Conflictos con la expresión “linguocentrismo”

Abogar por la abolición de lo que llamo “Linguocentrismo” me ha obligado a explicar reiteradamente que no busco “sepultar” el habla ni cortar las lenguas de las personas, tal como ocurre con el femi-nismo cuando se lo ve una “conspiración contra el sexo opuesto”, o con la crítica al logocentrismo cuando se la considera “antilogocen-trismo”. No es mi objetivo fundar un anti-sistema sino replantear la cuestión del conocimiento y el pensamiento humanos sobre bases más endebles y honestas.

10

Ensayo Fundamental

Cuestiones Conceptuales

He buscado definir categorías que alcancen a la literatura, la escritu-ra, el habla, la arquitectura y el resto de las manifestaciones del in-tercambio de sentido humanos.

Considere que he redefinido y adecuado terminología y he creado nuevas categorías, tenga por favor la paciencia de aguardar hasta haber revisado exhaustivamente el sentido que doy a cada término para analizarlos y cuestionarlos.

Por ejemplo, con las expresiones “narración” y “relato”, designo a fenómenos diferentes: narrar es exponer y relatar, proveerse de sen-tido. El origen de la palabra “relato” está en la latina “relatus”, don-de “latus” es llevado o producido. Escojo ver al término “relatar” como volver a producir o a presentar algo. Los humanos no pode-mos llevarnos los propios hechos sino una re-presentación, una imagen que les permita presentarse ante nosotros. Esa imagen de lo acontecido incluye también nuestro punto de vista, nuestra habili-dad para componer y nuestros intereses al respecto. Tomarse el tra-bajo de producir no se hace sin alguna finalidad del tipo: estudiar u organizar lo que nos rodea, acopiar experiencias o contrastarlas con otras ya registradas, ejercitar o reconocer al propio sistema, conocer a los otros, hacer catarsis, disfrutar, sufrir, etc. De modo que los hechos (de todos los acontecidos, solo los que escogimos) que hayan de presentarse (la presentación es producida en el humano) lo harán con diversas intermediaciones.

Si bien la adquisición de saberes y experiencias no se detendrá en tanto estemos viviendo, hay un momento en que consideramos sufi-ciente a lo percibido como para sacar una conclusión que, aunque no es definitiva, nos permite cerrar un ciclo y dedicar nuestra aten-ción a celebrar otros relatos, concluir unos que hayamos dejado pendientes o revisar aquellos cuyas definiciones no estén dando

11

Alejandro Guevara

buenos resultados en la aplicación práctica. En función de esto, de-fino al relato como:

El evento que acontece entre la producción de una presentación y la incorporación de un aprendizaje1.

Los seres humanos celebramos ese evento por nosotros mismos y también con sugerencias de otros. Voy a proponerle prestar atención tanto al modo en que nos re-presentamos a nosotros como a la ma-nera en que ofrecemos ayuda a otros para re-presentarse. He nom-brado a esas funciones “relatador”2 y “persona”3 respectivamente.

Un mismo relato no acontece dos veces ya que sólo el hecho de que hayamos celebrado uno antes nos ha hecho diferentes relatadores y personas. Luego, cada relato existe sólo en tanto está celebrándose.

Como le propongo que el resultado de la celebración de un relato es el acopio de algún tipo de riqueza a la que, en algunos campos, so-lemos llamar “saber”, le ofrezco mi definición:

1 La cuestión de la utilidad tal vez genere controversia, déjeme ampliarle la oferta en este punto. Por lo pronto, le adelanto que no sólo considero aprendizaje a la memorización de fórmulas matemáticas sino también a experimentaciones de todo tipo, incluidas las que puedan considerarse banales científicamente como la del placer.

2 Todos los humanos somos relatadores en tanto sondeamos, creamos y editamos unas percepciones, las asociamos en una presentación y evaluamos su resultado y posibilidades para archivar lo aprendido. Más en “Relatador-Persona”.

3 Del latín “per sonare”. Aprovecho la referencia a las máscaras del teatro griego que caracterizaban a los personajes por su modo de sonar. De este aspecto humano como generador y ofrecedor de contenidos me ocupo en “Relato y Narración”

12

Ensayo Fundamental

Saber es hacer un alto en el camino del aprendizaje, solo necesa-rio para actuar.

Saber es detener el crecimiento. Eso es útil pero solamente cuando debemos tomar determinaciones perentorias4. Decir “ya, definitiva-mente, sé” es decir “no necesito aprender más”. Y eso, la mayor parte del tiempo, no es cierto.

* * *

Le invito a salirse del lugar de confort que brindan los saberes “in-cuestionables”, para considerar un modo en que más probablemente acontezca el fenómeno del relato (que es la manera en que “acopia-mos” conocimientos y experiencias). Si se atreve a revisarlo y apli-ca la perspectiva en su práctica cotidiana, notará importantes cam-bios en su rendimiento y la calidad de lo que produzca.

* * *

4 Un cirujano sólo debe saber que es necesario amputar en el momento en que peli-gra la vida del paciente pero no debería dejar de investigar por considerar que “ya sabe” a riesgo de mutilar personas inútilmente en el futuro.

13

Alejandro Guevara

14

Relato y Narración

Relato y Narración

Herramientas fundamentales para ofrecer contenidos

Las herramientas que voy a ofrecerle aplican a todos los modos y medios de oferta de contenidos, desde el oral o escrito hasta la ci-nematografía o la música y desde la más increíble superproducción multimedia hasta la más improvisada oferta de noviazgo. Al finali-zar, podrá usted responder más satisfactoriamente las preguntas de la introducción.

Las ofertas de contenidos se hacen con el fin de que se celebren re-latos, son guías para celebrar relatos pero no relatos en sí mismas.

No podemos guardar los propios acontecimientos sino percepciones de ellos, que resultan de comparaciones con otras percepciones o saberes ya almacenados y organizados. El conocimiento nuevo, en-tonces, está también formado por conocimiento viejo. Ese saber previo, que ayuda a dar sentido a lo que ocurre, suele provenir del ser humano que relata su propia existencia (relatador) y de instructi-vos (contenidos) que le ofrecen otros. Si alguien lee un libro o ve una película puede, si quiere, celebrar un relato con ayuda de ese instructivo. Desde la producción de contenidos, nos toca trabajar buscando ofrecer buenos contenidos y procurar que estén disponi-bles en el lugar y el momento indicados para que los relatadores que estén dispuestos los puedan aprovechar.

15

Alejandro Guevara

Listado de herramientas 1. Produzca sabiendo que "ofrece" en lugar de pensar que "en-vía".

2. Es usted una persona-relatador aunque por momentos fun-cione más como relatador o más como persona.

3. Optimice las posibilidades de que los contenidos que ofrece se parezcan a los que han de establecer sus relatadores.

4. Revise la coherencia entre los "departamentos" de su pro-ducción oferente. 4.1 Autor - Autoridad

5. Clarifíquese qué es lo que ofrecerá y a qué relatadores.

6. No respete el texto sino el objetivo de la producción.

7. Haga un análisis concienzudo de las licencias, acuerdos y permisos por defecto y de los que espere otorgar, acordar u ob-tener.

8. Defina qué protagonismo asigna a sus canales de expresión y a los órganos de percepción de sus relatadores.

9. Evalúe la calidad del material que ofrece y del que ofrecen otros.

10. Esquema del circuito de ofrecimientos, solicitudes y estable-cimiento de contenidos (descripción de algunas funciones).

16

Relato y Narración

1. Produzca sabiendo que “ofrece” en lugar de pensar que "envía".

Usar esta herramienta implica desandar el prejuicio que llamo lin-guocentrismo (desarrollado en "La Muerte de la Lengua") que, en lo que respecta a este punto, apoya la creencia de que los contenidos, en lugar de ofertas de instructivos para generar percepciones (y lue-go, relatos) son "paquetes de percepciones" a ser "recibidas" por "destinatarios". De acuerdo con este concepto erróneo, los supuestos destinatarios poco pueden hacer con los paquetes excepto desempa-carlos correctamente.

De ninguna manera funciona así. Los seres humanos decidimos qué ofertas han de interesarnos, buena parte de lo que hay dentro de ellas y en qué medida sus instrucciones nos serán de utilidad. Esto no quiere decir que acertemos todas las veces, probablemente en los hechos ocurra casi lo contrario y dediquemos demasiado tiempo a procesar contenidos irrelevantes y tengamos poca habilidad para de-tectar a los que nos serían más útiles. Por eso mismo, para realizar (relatar) una vida más satisfactoria, siempre estamos buscando ajus-tar el modo de discriminarlos.

Estoy diciéndole que sus probables relatadores no absorberán “lo que les envía” sino que, eventualmente, decidirán prestar atención a lo que les propone. Y que sus propuestas consisten en unas recetas para que re-laten: vuelvan a producir a su modo. Y así, cada relata-dor celebrará su propio relato. Cuando una persona describe a otra un objeto desconocido, ofrece indicadores para que el relatador ge-nere percepciones parecidas a las que experimentó el ofrecedor. El relatador no percibirá lo mismo sino que, con ese instructivo y ayu-dado por percepciones de archivo, re-producirá o re-creará percep-ciones de algo que con suerte tendrá parecido con lo que han queri-do referirle.

17

Alejandro Guevara

Este procedimiento es bien diferente al del envío de un paquete de percepciones.

2. Es usted una persona-relatador aunque por momentos funcione más como relatador o más como persona.

Funcionamos como relatadores cuando tomamos elementos del en-torno (pueden ser hechos, materiales o conjeturas), los representa-mos, organizamos esas representaciones dándoles un sentido y lo acopiamos en nuestro almacén de saberes; y como personas cuando producimos y ofrecemos con sonidos, imágenes, olores, etc., mate-rial para guiar a relatadores en la generación de percepciones y les sugerimos el sentido que deberían darles organizándolo en ofertas (contenidos).

Si en este momento siente algo de confusión, está en el camino co-rrecto. Es que “relatador” no nombra a lo que hasta ahora conocía-mos como "relator", que es quien creíamos que "enviaba un relato", sino al responsable de un modo más probable de funcionamiento del relato (a quien antes llamábamos lector o espectador). Relatador no es, por ejemplo, quien emite palabras sino quien, ayudado por lo que se ofrece invocando palabras, crea o recrea una experiencia.

Las funciones relatador y persona coexisten entre diferentes seres humanos y también dentro del mismo, no obstante, parecen tener "vidas separadas". Por ejemplo, la habilidad en un aspecto no impli-ca habilidad en el otro: usted puede sacar grandes provechos de li-bros y películas o de conversaciones con amigos pero no ser bueno ofreciendo instrucciones para que otros relaten o, por el contrario, ser un buen productor de recetas para ofrecer a otros y no ser bueno para llevarlas a cabo. Conocemos a muchos buenos consejeros cuya vida es un desastre y a muchos humanos felices que no encuentran el modo de ayudar a serlo también a su entorno.

¿En qué medida saber sobre relatadores es útil para producir mejo-res contenidos?

18

Relato y Narración

Saber qué puede hacer nuestro “ofrecido” con nuestra oferta, en ca-so de aceptarla, es determinante para ayudarlo a disfrutarla o para orientarle sobre la medida en que le será de utilidad.

De modo resumido: los relatadores producimos y organizamos unas percepciones de lo que entendemos que ha acontecido en el mundo, tanto real como imaginario, relacionándolas con otras o con percep-ciones de archivo, de manera de encontrar algún tipo de explicación al acontecimiento (presentación). Y si el material alcanza para con-siderar un aprendizaje total o parcial, lo archivamos como nuevo co-nocimiento para interactuar mejor con el mundo y con nosotros mismos.

Saber cómo se funciona como relatador, además, mejorará sus posi-bilidades de crear diferentes “relatadores tipo”. Para chequear o hacer correcciones sobre su propio material, es preciso colocarse en lugar de un relatador con competencias e intereses similares a los de quienes se espera que acepten la oferta.

Las dos primeras herramientas descriptas hasta ahora son primordia-les para la oferta de contenidos. Su utilización debería verse en los hechos como una cuidadosa elección, producción y exposición de indicadores5, considerando los intereses y competencias de diferen-tes relatadores.

3. Procure que los contenidos que ofrece se parezcan a los que han de establecer sus relatadores.

Cada relatador establecerá, en la medida de sus competencias e in-tereses, cómo es el contenido de la oferta de la cual es objeto.

5 Definición más precisa de indicador en la herramienta 10, Esquema y descrip-ción...

19

Alejandro Guevara

En lo referente a las competencias, el background de cada relatador discrimina las posibilidades de establecer. Por ejemplo, quienes trabajan en medicina entenderán de diferente modo ciertos indicado-res de la serie Dr. House. En lo que respecta a intereses, son muchas las variantes posibles y van desde nuestra consideración sobre en qué medida puede sernos útil tal contenido hasta nuestros intereses económicos, emocionales o políticos. Por ejemplo, no relatamos del mismo modo con un periódico con el que estamos de acuerdo polí-ticamente que con uno con el que no lo estamos. Esto quiere decir que más allá de que usted crea haber ofrecido “un” contenido (Ocontenido), cada relatador establecerá que se le ha ofrecido lo que pueda y quiera (Econtenido).

Lo establecido incluso cambiará para un “mismo” relatador que de-cide relatar por segunda o tercera ocasión, como ocurre cuando ve-mos “nuevamente” una película: no solo porque mismo y nueva-mente no aplican ya que cada relatador se renueva con cada expe-riencia y una película cambia al variar el entorno sino porque los re-latadores tienen siempre conveniencias, obligaciones, razones o emociones6 diversas por las cuales considerarían llevar a cabo cada celebración.

Un contenido ofrecido debe tener la capacidad de guiar hacia unas percepciones, proponer una organización y brindar una posibilidad de conclusión (lógica, emocional, experiencial, etc.).

Los elementos que ayudan a producir percepciones son indicadores que iremos ofreciendo a nuestro probable relatador para que com-plete el "rompecabezas" de su cuadro de situación. De este modo, si usted expone un indicador, como por ejemplo una escena de un film donde se muestra una habitación vacía y se hace un zoom sobre un

6 LAPs: Licencias, Acuerdos y Permisos, ver definición en la herramienta 7.

20

Relato y Narración

cenicero con una colilla manchada con labial, muchos relatadores entenderán que deben guardar esa información porque habrá de ser-les útil más adelante. En cada relatador que lo advierta, el indicador habrá propiciado una percepción y cada una tendrá matices propios. Algunos, por ejemplo, creerán, uniendo esa percepción con otras, que ya conocen al asesino y otros pasarán de la certeza a la confu-sión. Algunos en lugar de lápiz labial verán sangre y quizá muchos no advertirán indicador alguno, por lo que será necesario redundar en la oferta hasta asegurarse de que cada relatador cuente con mate-rial suficiente para completar su presentación aun sin disponer de lo que perderá por distracción o ruido.

Hay distintos tipos de indicadores, que solemos organizar en se-cuencias, capítulos, partes de una zaga, etc. Lo que los aglutina en un contenido es el enfoque hacia una propuesta de conclusión, a la que los guiará una grilla o instructivo para el armado. La grilla es un mapa que propone un modo de valorar y archivar: un aparentemente “mismo” indicador indicará diferente si integra una grilla de sus-penso, una sensorial, una historia de amor o una humorística.

Las grillas proponen modos de organizar, que no necesariamente re-conocen una línea de tiempo y, si bien el modo cronológico es uno de los más difundidos y efectivos, hay otros con diversa relevancia temporal como algunos descriptivos. La incidencia del tiempo en un contenido atañe al género y de ningún modo a la estructura funda-cional del relato. Los estudiosos que colocaron el tiempo como va-riable estructural del relato se enredaron con la visión linguocéntrica que primó hasta el siglo XX, que llamaba al relatador despectiva-mente “destinatario”.

Entonces, para que sus relatadores establezcan de su oferta lo más parecido a lo que cree ofrecer, debe escoger y producir cuidadosa-mente cada uno de sus indicadores para ponerlos a su alcance, dise-ñar cada grilla o escoger una “preseteada” (género), “sintonizar” con sus conveniencias, obligaciones, razones o emociones y considerar

21

Alejandro Guevara

muchas variables como el momento histórico, cultural o económico en el que vaya a ser completado cada relato o la dispersión o los ruidos del ambiente. Los relatadores suelen estar por momentos dis-persos, no entender algo o simplemente han tenido que ir al sanita-rio.

4. Revise la coherencia entre los "departamentos" de su producción oferente.

Producir contenidos involucra a varias áreas especializadas con di-ferentes objetivos complementarios, entre ellos: logística, dirección, captura, exposición, grabación, etc. Esas funciones recaen sobre di-versos órganos en las personas, sobre diferentes funcionarios de una compañía o departamentos en una gran organización.

El modo en que considere al resto de los actores de su producción oferente (PO) será determinante de la calidad de su oferta. Si se ha entendido y sintonizado con el resto, tendrá más posibilidades de producir ofertas congruentes, sencillas de entender y efectivas. A poco de andar verá que gran parte de los desajustes o errores en los contenidos oferentes resultan de una mala coordinación entre los ac-tores o simplemente de ignorar su existencia. Los desajustes en la oferta redundan en más trabajo para el relatador, quien deberá atar cabos sueltos o resolver contradicciones (si decide tomarse ese tra-bajo, en la mayor parte de los casos no lo hará y no habrá relato).

Luego, cuando decida exponer un material, considere una ardua ta-rea de preproducción y un estudio concienzudo de cada una de las premisas. Puede usted trabajar sobre Romeo y Julieta y, si bien no conseguirá una entrevista personal con William Shakespeare, sí puede negociar con él a través de sus ofertas.

Al narrar, por ejemplo, se reporta al resto de una estructura de oferta de contenidos. Si hace su narración apoyándose en el ofrecimiento de un escritor, también él será parte de su producción oferente.

22

Relato y Narración

4.1 Autor - Autoridad

Lo que exterioriza cada humano no necesariamente es original. En nuestras palabras o gestos, hablan otras personas de las que hemos aprendido, grupos de personas organizadas en entidades a las que llamamos culturas, y personas aún más lejanas y desconocidas que (aún no sabemos de qué modo) nos han dejado grabados sus apren-dizajes en los genes. Así de complejo es saber quién es quien ofrece.

La función de autoridad7 suele ser ejercida por un colectivo de di-versos actores con diverso tipo de participación, intereses, LAPs, etc.

Los relatadores necesitamos establecer algún punto de vista desde donde ha sido observado lo que se nos ofrece para sincronizar nues-tra propia cosmovisión. Al establecer ese punto de vista, creamos una imagen del responsable de la oferta (Eautoridad). Cuando, por ejemplo, la autoría proviene de nuestra propia persona, nuestro rela-tador termina de establecerla revisando las LAPs que podamos tener acordadas con nosotros mismos y hasta nuestro estado de ánimo: tomamos menos seriamente algo que vemos triste si creemos estar deprimidos.

Cuando la oferta proviene de una producción oferente (otra persona, grupo de personas o productora de contenidos), establecemos la perspectiva y la responsabilidad del ofrecimiento considerando con nuestros conocimientos e intereses la Oautoridad. Todos los inte-grantes de un equipo de producción y en cierta medida hasta la humanidad, pasada y futura, se postularán para integrar cada autori-dad ofrecida.

7 Puede usted encontrar una definición más extendida al finalizar las herramientas. Vea en “La Muerte de la Lengua” cómo solemos confundir esta función con la de quien llamamos “autor” por prejuicio linguocéntrico.

23

Alejandro Guevara

Como productor y ofrecedor de contenidos deberá tomar decisiones precisas sobre su participación en la entidad a la que se postulará como integrante. De acuerdo con su conformación, podrá aspirar a diferentes licencias, acuerdos y permisos (LAPs) que serán determi-nantes de las probabilidades de éxito de sus ofertas.

5. Clarifíquese qué es lo que ofrecerá y a qué relatadores

Nadie relata si no considera que con eso ha de obtener algo, desde aprendizajes lógicos y racionales hasta vivencias de sensaciones, in-cluidas todo tipo de situaciones reales o imaginadas.

Para asegurarnos de que alguien pueda relatar con ayuda de lo que le ofrecemos, es preciso que nuestro instructivo sea amigable y ten-ga algún tipo de coherencia interna dirigida hacia el objetivo que nos proponemos que considere. No siempre esta experiencia o aprendizaje propuestos estarán explícitos porque tal vez no sean ex-plicables con palabras o ni siquiera sean del todo conscientes (un ofrecedor, por caso el testigo de un delito, puede describir unos hechos intentando ser objetivo, y sin embargo torcer la balanza “in-conscientemente” hacia alguien de quien sospecha por su aspecto o raza). Aun considerando que hay muchos imponderables, debe pre-guntarse qué provecho creerán obtener sus relatadores y estudiar la relación entre sus promesas (manifiestas o encubiertas) y las expec-tativas que podría favorecer en ellos para estar a esa altura, honrar sus compromisos y conservar sus licencias para futuros contenidos.

Usted también ha de tener motivaciones que le lleven a ofrecer con-tenidos. Son muy variadas y pueden ser altruistas o materialistas pe-ro son diversas de las que tendrán los relatadores para aprovechar sus Ocontenidos.

He escuchado muchas veces a creativos diciendo: "yo solamente produzco para mí mismo". Alguien pinta un cuadro y manifiesta que no ha querido trascender con su pintura sino solo disfrutar del pro-ceso de la creación. Aun tratándose de un proceso auto-satisfactorio

24

Relato y Narración

(con perdón de la expresión), estará habiendo relato cada vez que una persona ofrezca algo con lo cual relate el relatador que la com-pleta. De cualquier modo, buena parte de las manifestaciones de desinterés son sólo frases de mercadeo destinadas a aumentar el va-lor "espiritual" del contenido ofrecido de modo que se pague más.

Para aprovechar esta herramienta, cuando esté produciendo, vea si puede resumir en una frase (o sensación) su oferta: le servirá para dar coherencia a los indicadores y al resto de los elementos de su puesta en escena.

También revise qué tipo de relatadores cree usted que podrían inte-resarse en su oferta (por más que muchas veces los relatadores ter-minen siendo los menos pensados). Tener una idea o perfil tipo del relatador que toma como objetivo, mejora las posibilidades de ajus-tar la interpretación. No se dirige uno del mismo modo a humanos de diferentes edades, culturas, intereses, etcétera aun cuando crea ofrecer un mismo contenido. El ajuste es útil, por ejemplo, para es-coger la terminología o las imágenes adecuadas o evitar largos pasa-jes explicando lo ya sabido. Aun así, considere que puede ofrecer a diversos relatadores, con lo cual, si aguza su ingenio, podrá entrete-jer material para todos. Muchas de las producciones geniales tienen algo que ofrecer a diferentes tipos de relatadores como Los Simp-son, que ofrecen contenidos simultáneos para una gran variedad de edades, culturas, etc.

El ofrecedor no hace reír al público sino que pone a su disposición una guía para que algunos integrantes celebren risas. Si lo ve de este modo, entenderá por qué algunos relatadores reirán a carcajadas y otros permanecerán incólumes masticando sus palomitas de maíz y por qué hasta es posible que algunos se enojen o se sientan ofendi-dos.

Por lo tanto, no solo debe considerar a quienes se dirige y cerciorar-se de que ellos estén en el radio de alcance de su oferta sino también procurar que quienes puedan sentirse ofendidos o no considerados

25

Alejandro Guevara

no sean “ofrecidos” involuntariamente, por ejemplo, explicitando LAPs como “contenido no apto para relatadores impresionables”.

6. No respete el texto sino el objetivo de la producción

Es probable que, para relatar en sintonía con mi relato, deba revisar los conceptos y definiciones de “La muerte de la lengua”, de lo con-trario es probable que lo que sigue le resulte confuso o incoherente.

He escuchado a profesores bienintencionados cometer el pecado de aconsejar a sus alumnos de locución que se dirigían a un papel es-crito: “respeta el texto”. Este ofrecimiento puede conllevar la con-fusión que llamo “fetichismo del soporte” del que hablo en "La Muerte de la Lengua". Por otra parte, creer que las palabras son lo que hay en el papel es también linguocéntrico. Las palabras no salen de las lenguas y penetran los oídos, ni salen de los papeles y pene-tran los ojos, son entre y no desde o hacia. El texto de tinta en el li-bro no es la oferta sino un grabado aunque por fetichismo lin-guocéntrico8 nos cueste verlo de otro modo.

Luego, lo que debe respetar es el objetivo de la producción oferente, para lo cual deberá decidir desde la perspectiva de la Oautoridad, cuál es la oferta - objetivo.

Lo que debería sugerir el profe, a mi entender, es que la manifesta-ción física del narrador debería sintonizar con el resto del equipo de Oproducción. O si por ejemplo van a trabajar con Romeo y Julieta, acordar sobre lo que entiendan que ha querido ofrecer Shakespeare, lo cual implicará necesarias negociaciones y actualizaciones.

8 “El soporte fetiche” Página 57.

26

Relato y Narración

No obstante, tal vez el profe pueda ofrecer que, en tanto narrador (integrante del equipo de producción), el estudiante debe ceñirse a la propuesta e intereses de la autoridad que “emana” del texto sin agregarle ni quitarle. Pero esto no es posible porque la autoridad no es una función que emane sino que se propone y establece para cada oferta, con lo cual, si ha considerado que hay un unívoco referente u origen universal, está pensando de modo linguocéntrico (logocén-trico). Debería el profe en primera instancia discutir con su alumno sobre la autoridad a proponer ya que cualquier aporte a una produc-ción oferente re-crea la Oautoridad y desconocer un aporte o tratar de hacerlo desaparecer es una actividad ímproba y hasta puede ser deshonesta.

Unos buenos aunque fallidos intentos de salirse del linguocentrismo han sido, aprovechando la amplitud que favorece la etimología de texto como tejido, proponer que el "destinatario" también estaba considerado en el texto o que el contexto era parte del texto. Pero no han sido suficientes. Puede usted encontrar muchas ofertas donde en la misma frase se propone "texto" como soporte, como contenido ofrecido y como establecido y, por supuesto, nunca como órgano in-teractivo. Si puede ahora ver que se ha aludido a fenómenos diferen-tes sin advertirlo, entenderá por qué a menudo nos hemos enredado con tan diverso “tejido” hasta ya no poder desanudar la madeja.

Llamar lectores a los humanos que relatan con libros proviene de la misma confusión. La acción de leer debería considerarse similar a la que hace la lectora de una PC, por ejemplo: tomar unos datos y po-nerlos a disposición de algo o alguien más, incluso recodificarlos, pero no interpretarlos ni mucho menos relatar. Compruebe que de este modo actuamos los humanos: tenemos la opción de leer párra-fos enteros sin haber entendido o retenido una sola palabra. Eso ma-nifiesta que la acción mecánica de la lectura es bien diferente de la de hacer algo con palabras.

27

Alejandro Guevara

7. Haga un análisis concienzudo de las licencias, acuerdos y permisos (LAPs) por defecto y de los que espere otorgar, acordar u obtener.

Entre la producción de ofertas, el establecimiento de contenidos y la celebración de relatos, existe lo que llamo “LAPs”: licencias, acuer-dos y permisos, que usted debe considerar cuidadosamente al mo-mento de ofrecer.

Desde el punto de vista de la persona (es decir de quien ofrece contenidos a relatadores), las licencias se obtienen: al colocar su oferta en un periódico, una sala de cine, una oficina, lo mismo que al ofrecer desde un puesto jerárquico por ejemplo, podrá invocar di-ferentes licencias. Esto siempre de acuerdo con cada relatador, un mismo periódico puede ostentar una licencia de credibilidad para ciertos relatadores y no lograrla con otros. Los permisos los otorga usted a sus probables relatadores, por ejemplo cuando califica su contenido como no apto para ciertas edades o personas impresiona-bles, etc. Como ocurre con toda norma o acuerdo, pueden ser respe-tados o transgredidos y pueden incluso invocarse para generar ex-pectativa, como cuando a los niños se les dice "no tomes la leche" con la intención de que la tomen. Los acuerdos suelen provenir de negociaciones entre licencias y permisos y resultan, por ejemplo, en licencias solo vigentes en tanto se cumpla con permisos o en permi-sos que regirán en tanto se obtengan licencias. También se negocian acuerdos sobre los usos o significados de ciertos términos o los ámbitos de validez de los parámetros.

Las LAPs en ocasiones son explícitas y en otras no, pueden o no ser conscientes y ser transparentes y honestas y también capciosas o deshonestas. También pueden ser expuestas, subyacentes, entendi-das, sobreentendidas, malentendidas, etc.

28

Relato y Narración

Al momento de ofrecer su contenido debe considerar qué LAPs re-quiere, con cuáles cree contar y el modo de obtener las restantes, in-cluso durante la exposición puede presuponer que irá ganando cre-dibilidad y proponer desde ese momento tesis más arriesgadas.

Erróneamente puede pretenderse que no hay LAPs solo porque la negociación no ha quedado explícita para alguien. Sabrá de ellas cuando las incumpla, como acontecerá si, por ejemplo, no respeta los derechos a la intimidad o de la niñez, consagrados en el pacto de San José de Costa Rica para Occidente. Además de observar las ex-presadas en leyes y reglamentos, preste especial atención a las con-cretamente no escritas para ajustar sus ofertas: la razón del fracaso de muchos Ocontenidos es el haber valorado LAPs de forma erró-nea o directamente no haberlas considerado.

Una LAP no escrita, por ejemplo, es la que surge de la promesa de valor de una oferta. Si usted ofrece a un relatador su contenido con la frase: “¡ni te imaginas lo que encontré en la calle!” y su relatador circunstancial acepta con un “¡dime!”, usted se ha comprometido a exponer un acontecimiento de gran valor para ese relatador de acuerdo con el cual obtuvo licencia para extenderse. De este modo, si es enormemente singular y valioso, podrá tomarse más tiempo y retroceder en el preámbulo hasta tal vez un “cuando yo era niño…”, y de no serlo tanto, deberá ir más rápido al punto. Pongámosle números: si va a referir que encontró 1$ tendrá una licencia de tiempo menor que si se tratara de 1000$ y mucho menor que si se tratase de un tesoro perdido. Aquí mismo puede ver cómo las ofer-tas no pueden valorarse sin considerar a quién se le ofrezcan: el di-nero (tanto como el amor o la ciencia) es de distinto interés para di-ferentes relatadores. Si equivocando su juicio sobre el relatador se extiende, por ejemplo, de más recibirá una reprimenda aunque no recuerde haber firmado ningún acuerdo.

Cuando se crea artísticamente, siempre se está en los bordes de los acuerdos pero si se transgreden y no se ponen a disposición los indi-

29

Alejandro Guevara

cadores necesarios para celebrarlo, pueden, por ejemplo, ofrecerse involuntariamente contenidos ofensivos. No obstante, no toda reac-ción adversa implica contenidos ofensivos, en ocasiones la reacción, incluso violenta, ha sido buscada: la oferta puede ser movilizadora.

Géneros como LAPs

En el punto tres he propuesto que los géneros parten de un acuerdo (son grillas pre-acordadas) pero muchos tardan en ser acordados por todos como el del videoclip, que fue criticado duramente por algu-nos relatadores hasta que comprendieron su lógica interna.

8. Defina qué protagonismo asigna a sus canales de ex-presión y a los órganos de percepción de sus relatadores.

Sus medios y canales de expresión exponen sus indicadores a los re-latadores. Por ejemplo, con un proyector de video puede exponer contrastes de luz que sugieran un rostro. Pero usted no estará en-viándole uno a su relatador, en el sentido estricto de “envío”, porque eso no puede hacerse de acuerdo con el punto de vista de este ensa-yo. Y si lo hiciese en el sentido estricto, no sería bien visto, como no fue bien recibida la cabeza del caballo en El Padrino.

Que usted trabaje con cámaras y proyectores no significa que sólo ofrezca indicadores para percepción de imágenes. Con esos mismos indicadores puede también ayudar a percibir olores, sonidos, calor, etc. Lo mismo si usa canales sonoros, además de ayudar a percibir sonidos, puede indicar cómo percibir imágenes, durezas, sabores y terror o sosiego. Habitualmente son varios los canales que, a modo de co-Onarradores, integran en conjunto un Onarrador.

30

Relato y Narración

Los órganos de percepción de los relatadores suelen actuar simultá-neamente, coordinados por el sistema de percepción9. Debe conside-rar qué espera que esté haciendo cada órgano de sus relatadores du-rante su exposición y no dejar, en lo posible, ninguno librado al azar. Procure apelar a todos no solo creando indicadores en su oferta sino también cuidando detalles hasta del entorno de la exposición. Por ejemplo, una sala con excesiva temperatura ambiente no ayudará a muchos de los indicadores de una película sobre supervivencia en el hielo.

Cada vez disponemos de más dispositivos u órganos de exposición y percepción gracias a las nuevas tecnologías. Las potencialidades y características de cada oferta dependen del tipo de dispositivos de captura o exposición con que cuente, de la habilidad para la captura, producción, edición y exposición y también de las prestaciones y habilidades de los órganos de percepción de sus probables relatadores.

También tenga en cuenta que diferentes relatadores dan mayor rele-vancia al foco que ofrecen diferentes dispositivos de entrada y, así como hay relatadores que favorecen la óptica de los dispositivos de imagen, los hay más auditivos, táctiles, olfativos, racionales, emo-cionales, etc.

Con frecuencia se confunde el dispositivo de entrada con el órgano de percepción: se cree que son lo mismo el sentido de la vista y el órgano de percepción de imágenes. Tenga en cuenta que las imáge-nes se componen, como todas las percepciones, de lo que excita a los dispositivos de entrada10 (por ejemplo, los ojos), que luego será

9 Más sobre órganos de percepción, incluidos los de razones o emociones, en “Re-latador-Persona”.

10 No siempre una imagen “nace” en los ojos, puede sentirse por otro dispositivo de contacto y hasta prescindir del contacto con el exterior (ser imaginada).

31

Alejandro Guevara

procesado en el resto del órgano con imágenes de archivo, enmar-cado por LAPs (lo que se debe o conviene ver o no, lo que se espe-raba ver), etc. A su vez los órganos de percepción participan en “órganos de interacción” donde se sirven de órganos y dispositivos de salida o actuación, como la mano que oprime para que las yemas de los dedos perciban consistencia, etc.

La reducción de los órganos de percepción a dispositivos de entrada a los que se confundió en el nombre “sentidos”, considerados como receptores pasivos, sumado a la creencia de que los dispositivos de actuación envían y los de percepción reciben, en lugar de todos formar parte de un sistema de interacción con el entorno, ha dado lugar a lo que llamo “linguocentrismo”, que dictaminó que los de exposición tenían mayor estatus que los de percepción (simplifican-do, la lengua que el oído) por ser el origen11.

El habla como resultado de un órgano especial

El sistema linguocéntricamente llamado “habla”12 constituye un órgano de interacción social. El habla organiza, reproduce y poten-cia el sistema de acumulación y descarte de experiencias sensoriales pero no es extrasensorial13. Desde mi punto de vista, no se ha proba-do que la posibilidad de amar sea menos mágica que la de hablar, pese a que esta última no sea, por el momento, compartida con el resto de los seres vivos conocidos. Aseverar lo contrario es despre-

11 Logocentrismo en “La Muerte de la Lengua”.

12 Justificación en “La Muerte de la Lengua”

13 La confusión sobre los sentidos llevó también a creer que existía una línea entre física y metafísica. El bibliotecario Andrónico de Rodas colocó unos escritos de Aristóteles en estantes diversos, producto de su propio relato sobre qué contenía cada contenido (sugerido tal vez por Aristóteles y sus antecesores). Esa, a mi juicio, es la única prueba de la existencia de tan temeraria división del universo.

32

Relato y Narración

ciar a otros modos de inteligencia, colocando lo racional por sobre lo emocional, por ejemplo. Y despreciar es no poder apreciar, una limitación del observador, no de lo observado.

9. Evalúe la calidad del material que ofrece y del que ofrecen otros.

Si desanda sus viejas creencias y prejuicios, verá que podrá referirse a la calidad de la oferta de contenidos con un criterio relativamente objetivo. Las herramientas que le proporciono indican parámetros para evaluar tanto la oferta de contenidos como la celebración de re-latos, pero esos calificativos solo servirán para establecer en qué medida se cumplen los objetivos tanto de ofrecedores como de rela-tadores.

Si revisa el ejemplo de la herramienta siete, donde le describo cómo, de acuerdo con el interés que tenga la oferta para el relatador, podremos tomarnos más de su tiempo en la exposición, verá cómo puede sustentarse la expresión: “esta película es muy larga”, por ejemplo. No hemos de discutir el criterio del relatador que manifies-te descontento pero sí estudiar si las razones del descontento pudie-ron zanjarse en la oferta y aprender. Si ha sido que la oferta no esta-ba dirigida a ese tipo de relatadores, la producción oferente puede revisar sus criterios publicitarios o el relatador, su modo de evaluar los ofrecimientos. Pero si muchos relatadores-objetivo14 manifesta-

14 Siempre hay un relatador-objetivo aun cuando muchos productores oferentes no se lo confiesen. Puede ser ambiguo y pretencioso como “toda la humanidad” o pre-ciso y pretencioso como algunos targets publicitarios. En todos los casos, el objeti-vo comienza a delinearse desde el momento en que se elige el soporte (las imáge-nes presuponen a quienes pueden ver, las palabras a quienes oyen y hablan, y hasta discriminan por lengua, dialecto y registro, etc.) y continúa con la elección del te-ma, el modo de abordarlo y hasta la circunstancia de exhibición.

33

Alejandro Guevara

ran que es larga, estaríamos ante un seguro error de cálculo de la producción a resolver para la próxima.

También es posible que muchos relatadores no considerados en el objetivo, se manifiesten satisfechos y hasta fascinados por lo que han relatado ayudados por ese contenido “defectuoso”. Si tenemos en cuenta que cada relato se completa en cada relatador con sus competencias e intereses, muchos de los cuales están fuera del al-cance de nuestra comprensión, eximiremos a la oferta de aciertos y fracasos no relacionados directamente con nuestras intenciones15. O buscaremos en la incertidumbre elementos de interés para los rela-tadores, como en el caso de los programas de TV que se nutren del minuto a minuto y prolongan los segmentos que miden bien aun desconociendo las razones del “éxito”. Busque en internet el genial ejemplo del “yo no fui” de Bart Simpson.

El mismo criterio que para “larga” (como calificación para una película), puede aplicarse para valuar otros parámetros. Esta herra-mienta no indica que juzgue en función de su gusto sino de la fun-cionalidad (de cualquier modo el gusto es en cierto modo funcio-nal). Si la oferta ha funcionado aproximadamente como se lo propu-so, entonces puede arriesgar que ofertas similares hayan de funcio-nar del mismo modo en circunstancias similares con relatadores homólogos. Y una vez que se hayan agotado los relatadores o se haya cansado de la rutina, deberá poner a trabajar nuevamente su creatividad para diseñar o producir nuevas ofertas.

15 No quita que disfrutemos de los réditos de nuestros errores y hasta que alguien pueda decir a quienes aportan recursos a su producción que las consecuencias for-tuitas en realidad eran buscadas.

34

Relato y Narración

10. Esquema del circuito de ofrecimientos, solicitudes y establecimiento de contenidos (descripción de algunas funciones).

Propongo que los seres humanos somos a la vez relatadores y per-sonas. De modo que, cuando integramos producciones tanto uniper-sonales como grupales, somos personas-relatadores o grupos de personas-relatadores.

Dentro de este esquema, funciona el viejo circuito de contacto des-cripto por Jakobson como emisor-mensaje-receptor (E-M-R) pero la manera en que lo considero es substancialmente diferente. El modo de ver linguocéntrico del siglo XX ha intentado explicar la interac-ción humana descomponiendo y complejizando la estructura E-M-C

35

Alejandro Guevara

que les mostraré como un simple auxiliar de contacto. Véalo en este dibujo:

Ejemplificar con teléfonos celulares nos permite ver la calidad de conectores de los actores nombrados en el esquema. E-M-R son elementos tecnológicos que permiten conectar pero que no son lo que conectan aunque puedan incidir algo desde la calidad de la co-nexión, los ruidos y las LAPs asociadas al medio.

Si pensáramos, como propuso McLuhan, que el medio es el mensa-je, podríamos ahora preguntarnos sobre el mensaje que es la telefon-ía celular, la internet o las redes sociales pero, aun tomando como valedera la premisa mensajera para saber algo sobre el intercambio de sentido entre humanos, deberíamos salirnos del concepto deter-minista del mensaje sobre la celebración de relatos. Conocer un mensaje (la manifestación grabada de una o unas ofertas) nos dice muy poco sobre qué se relatará con ello y hasta siquiera si ha de re-latarse algo.

36

Relato y Narración

Vea el caso de ponernos a analizar el posible mensaje del ejemplo, “Te estoy esperando”.

¿Qué clase de conjeturas “científicas” podemos hacer con solo esa información, en relación con la oferta de contenidos o la celebración de relatos si no contamos además con datos sobre LAPs y circuns-tancias en que se haya celebrado algo?

Si, por ejemplo, desconocemos los acuerdos entre ambos que se hacen tangibles hasta en el suministro del número o pin de los dis-positivos, ¿podemos decir que se negocia un encuentro, sin siquiera saber si alguno de los usuarios está observado, como lo estaría un acosador, entonces el mensaje llega pero se deriva a la papelera?

El esquema E-M-R solo alude a tecnología al servicio de la pausa y de ninguna manera conforma un modelo completo de intercambio de sentido. El emisor es solo el dispositivo que envía un mensaje y el receptor el dispositivo que lo recibe pero no podemos considerar que un teléfono celular es el equivalente a una persona sino solo un dispositivo al servicio de alguien para enviar un mensaje. Lo mismo vale para el receptor. Suponiendo que el proceso de envío y recep-ción del mensaje hubiese sido exitoso, lo mejor que podemos espe-rar es que “el mismo” texto que se colocó en el emisor esté siendo reproducido por el receptor. Esto es, sin distorsiones o problemas de decodificación. Pero, aun dada esa situación, ¿podemos estar segu-ros de que el propietario del receptor ha entendido el ofrecimiento con claridad solo porque las letras estaban legibles en su dispositi-vo? Por supuesto que no, porque se trata de fenómenos diferentes. El grabado, sólo remite a unas instrucciones para relatar que fun-cionan como recetas para hacer pasteles: no son pasteles ni tampoco las propias instrucciones.

Podemos incluso considerar que entre el dispositivo emisor y la per-sona que ofrece también se encuentran los dedos que digitan sobre el teclado de modo que también podríamos considerar que los dedos

37

Alejandro Guevara

son emisores, en este caso de pulsos de presión que son recibidos por el teclado del dispositivo emisor, que aquí funcionará como re-ceptor de esas presiones. Varios sistemas de emisión y recepción suelen estar encadenados para ayudar a poner grabados a disposi-ción de relatadores pero ninguno de ellos cumple una función ni si-quiera tangencialmente similar a la del ofrecimiento de contenidos o la celebración de relatos. Son solo auxiliares que permiten transpor-tar y eventualmente pausar unos grabados.

El mensaje sigue siendo mensaje aunque nadie vaya a revisar jamás su dispositivo receptor, su compañía ha de cobrarle por el envío in-dependientemente de que sea o no leído o de cómo sea entendido. Pero si por el contrario definimos que el mensaje se completa o es en función de lo que el “receptor” haga con él y consideramos que un receptor no es sólo un dispositivo sino lo que en esta teoría lla-mamos “relatador”, de modo que el supuesto mensaje ha de nacer entre emisor y receptor, entonces jamás nadie puede contactar con un mensaje que no lo involucre, lo que sólo puede acontecer en el mismo momento de relatar. En ese caso, de ningún modo aludiría-mos con mensaje a lo que puede verse en la pantalla del dibujo.

En lo que respecta a la supuesta existencia de un “sentido de circu-lación”, la enorme red de mensajes de las redes sociales nos exime de mayores explicaciones sobre si es útil establecer un sentido de derecha a izquierda, de arriba hacia abajo, de emisor hacia receptor. Del mismo modo que es ocioso saber si la Internet es un fenómeno de “bajada” más que de “subida” o viceversa, es ocioso determinar si ha habido un primer mensaje que desató al resto o si fue una búsqueda de contacto lo que disparó al sistema.

Sigue una breve descripción de la organización del ofrecimiento de contenidos por parte de personas-relatadores, que se complementa con el modo en que nos sean de provecho a los relatadores-personas que describo en la tercera parte del ensayo.

38

Relato y Narración

Contenidos O y E

Los Ocontenidos son instructivos que una producción ofrece a un relatador, para que celebre un relato por sí mismo. Se integran con uno o varios indicadores que postulan un aprendizaje (o varios). Son instrucciones de uso para relatadores. Sugerencias para usar instru-mentos humanos, que están delimitados o definidos por LAPs ante-riores (negociados en cada relato) y posteriores.

Cuando un relatador se apropia de una oferta (lo que es capaz o le interesa), para celebrar un relato establece un Econtenido. Cada vez que lo haga establecerá uno distinto, aún si celebrase creyendo que interactúa con el mismo Ocontenido (no es estrictamente posible porque el entorno es parte de cada Ocontenido): si alguien relata va-rias veces con una película, dará forma a Econtenidos diferentes cada vez.

Cualquier sección o sub parte de un Ocontenido puede a la vez fun-cionar como Ocontenido: es habitual en un buen sit com, como “Modern Fámily”, por ejemplo, encontrar ofertas para celebrar va-rios relatos.

Para desactivar el linguocentrismo propongo dejar de usar “contenido” para referirse al soporte donde se graban ofertas y llamarlo: audio, texto, CD, video, etc.

Curiosamente pasamos buena parte de la vida produciendo “el gran contenido” que ofrecer de nosotros para relatar nuestra existencia, y no obstante, cuanto más sabio, menos recursos necesitará: una an-ciana reunió a su familia en su lecho de muerte y viendo a sus deu-dos a los ojos antes del último suspiro dijo “ha estado todo muy bien”. El humorista español Pedro Muñoz Seca dijo ante el pelotón de fusilamiento: Podréis quitarme el dinero, las propiedades, incluso la vida, pero el susto que tengo en este momento no me lo quitaréis jamás.

39

Alejandro Guevara

Grilla (Género)

La grilla es la estructura de una presentación o un contenido (O y E): Un juego de relaciones, un esquema de las probables relaciones en-tre percepciones, suficiente para arribar a una conclusión o saber parcial o total sobre algo. Cohesiona el contenido al orientar los in-dicadores hacia una propuesta de conclusión o aprendizaje. Puede apoyarse en razones o emociones, o en ambas. Relatadores y ofre-cedores tendemos a archivar grillas que han funcionado satisfacto-riamente a modo de “plantillas”, y antes de crear una nueva, vemos si una pre seteada puede aplicar. Cuando una plantilla exitosa se ge-neraliza, adquiere la categoría de género. Los géneros permiten aho-rrar tiempo y afinar el ajuste entre ofertas y establecimientos, in-formando sobre por ejemplo dónde colocar el foco, qué relevancia tienen en la oferta las emociones o las razones, cuánto tiempo insu-mirá la exposición, etc. Proponen parámetros de tiempo, de “fantas-ía” o “realidad”, de humor, ironía, violencia, tipos de narrador, etc.

Muchas ofertas tienen por único objetivo que relatemos cómo fun-ciona un género. Algunos Ocontenidos llevan instructivos de su propio género o de especificidades propias de ese uso en particular.

No obstante la variedad disponible, los ofrecedores siempre estamos atentos a crear o recrear géneros, cuando no contamos con uno que se ajuste a una nueva situación o para sorprender o romper estereo-tipos ya no funcionales. También mezclamos dando lugar a sub-géneros, como en medios masivos el informercial que deviene del informativo y el documental; el docureality, de documental y reality show, etc.

Una descripción siempre tiene grilla: nadie describe sin un objetivo o punto de vista, que incluso puede situarse en lo que no se descri-be. No hay oposición entre narración y descripción en tanto no hay descripción sin narrador.

40

Relato y Narración

Producción oferente

Es la organización que se dedica a producir y ofrecer contenidos. Puede tener varios integrantes o integrarse en una sola persona. Se ocupa tanto de la búsqueda del objeto a proponer, como de la reco-lección de material, la producción de indicadores, la organización en una grilla, y la exposición.

Cubren estas áreas tanto la Warner Brothers como una persona que justifica su llegada tarde a casa. Y en ambos casos la suerte para sus ofrecimientos es difícil de prever.

Indicadores

Son las “pistas” o indicios que integran los Ocontenidos. Los pro-ducimos con órganos y dispositivos de captura, y su objeto es guiar a los relatadores a construir percepciones. Pueden crearse tanto con imágenes (de video, sonido, olores, texturas…), como con diálogos, secuencias, escenas, o capítulos, y exponerse para uno o varios ca-nales de contacto de los órganos de percepción como el auditivo, el visual, el textual, el emocional etc. Un Ocontenido puede funcionar como indicador de otro Ocontenido, y también un solo indicador puede ser suficiente para un Ocontenido.

Todos los indicadores de un mismo Ocontenido deberían estar al servicio del objetivo propuesto, aunque muchos lo hagan de modo tangencial, como aquellos que sugieren “pistas falsas” o los que describen personajes o contextualizan. Uno de los trabajos más difí-ciles de un proceso de producción es descartar indicadores muy lo-grados pero que desvían el foco del objetivo.

Los relatadores luego estableceremos indicadores, y con ellos gene-raremos percepciones (siempre de acuerdo con nuestras competen-cias e intereses). No suele haber Econtenidos idénticos ni tampoco Eindicadores idénticos: es habitual a la salida del cine escuchar a re-

41

Alejandro Guevara

latadores discutiendo sobre si con tal o cual “acontecimiento”, ele-mento o mirada, el ofrecedor quería indicar tal o cual cosa.

Un ofrecimiento debe contar con indicadores redundantes para sor-tear las pérdidas de atención o la incompetencia de algún relatador sobre algún tema.

Autor (autoridad)

La función de autoría de un contenido (O y E) desprovista de lin-guocentrismo, “descompone” la vieja figura de autor en: la función soporte (que propongo seguir llamando autor), la función de punto de vista y responsabilidad por una oferta (Oautoridad), y la función de punto de referencia establecido por cada relatador (Eautoridad).

Autor: propongo usar esta palabra para aludir a la manifestación física de la persona o asociación que condujo la producción de un Ocontenido. Quien solemos corporizar en la persona con la que tal vez dialogaremos tiempo después, por ejemplo, de relatar con un li-bro16, para pedirle un autógrafo. A quien, se asignarán legalmente los derechos de autor. Pero esa persona ya no es la anterior, aunque su aspecto pueda mantenerse relativamente similar (si pudiésemos considerar que la falta de cabello es similar a su abundancia, o que la abundancia de abdomen es similar a su escasez).

16 El uso no linguocéntrico de la frase “relatar con un libro” alude a lo mismo que “hice un pastel con una receta”, no indica que se utilizó el papel donde se escribió la receta para el preparado sino que se hizo con la ayuda del grabado de unas ins-trucciones.

42

Relato y Narración

Oautoridad: La función de Oautoridad no indica propiedad de la idea sino responsabilidad por el ofrecimiento. Puede colocarse en una persona física o en una organización17.

La Oautoridad promueve la oferta, dirige el proceso de producción para lo cual procura un guión, unos actores y unos dispositivos de captura y publicación, y los instruye dando coherencia al producto (si un actor toma determinaciones propias y estas son incorporadas a la oferta, ese actor forma parte también de la Oautoridad). Provee los recursos: para el relatador esto puede ser relevante a la hora de valorar la oferta ya que el origen de los recursos puede generar compromisos que la modifiquen. Y propone LAPs: posiciones de prestigio u objetividad, acuerdos sobre género y perspectivas, y permisos como limitar por edad, pertenencia o afiliación.

Eautoridad: cada relatador establece (siempre que relate) una Eau-toridad para cada relato: determina quién le ofrece, desde dónde lo hace. No hay ofrecimiento humano que no reconozca cuando menos un foco: el de la humanidad. Siempre sabremos (podremos estable-cer) algo del oferente, por ejemplo, que es humano, que tiene cierto conocimiento del uso de medios: si el soporte es una pintura, cierto

17 Y sus referentes: en cada una de nuestras expresiones, habitan incontables “voces”, como las de la cultura, las del deber ser, las de nuestros padres, guías espirituales, enemigos, las de nuestra descendencia, las de personajes de nuestros sueños, y otras que ni siquiera imaginamos. Son tantos e intervienen con tanta vehemencia que en ocasiones es difícil saber si hay algo original (creado íntegramente por esa persona) en cualquier manifestación humana. Con las debidas disculpas a Jorge Luis Borges, relato con una de sus poesías que las piezas del ajedrez creen librar sus propias batallas sin advertir que una mano las designa; que la mente humana que guía la mano, no advierte que otra, sobre ella lo hace, y que esa otra mano cree ser quien decide, sin advertir…No digo con esto que todos seamos irresponsables de lo que hacemos sino que interactuamos e interdependemos mucho más de lo que creemos o advertimos.

43

Alejandro Guevara

dominio de la técnica, si es un escrito, del habla y hasta el idioma que utiliza.

Entiendo que la muerte del autor ha sido un buen intento (aunque insuficiente) para desactivar el linguocentrismo, pero desalojar la figura “todopoderosa” no debería hacernos perder de vista la exis-tencia de la función de autoridad. Muchos de los que se escudan con la proclamada muerte del autor, sólo buscan evadir responsabilidades por sus ofertas.

Onarrador y Enarrador

Es cada realizador parcial de las E y O autoridades. El aspecto “vi-sible” de una producción oferente, su manifestación “fisica”. Cada vez que consideramos que cierta cantidad de material oferente con-forma “una” oferta (“un” Contenido Oferente), hemos encontrado a su narrador (O y E). En un audiovisual, no hay un Onarrador oral y uno visual independientes, sino que el Onarrador resulta de la inter-acción de ambos (puede sumar si es coherente o restar si no lo es).

Cada relatador establecerá de acuerdo a sus competencias e inter-eses, quien le narra cada oferta (narradorE).

Las calificaciones de omnisciente, observador, protagonista, etc. in-dican diferentes puntos de observación del Onarrador. Pero no nece-sariamente diferentes Onarradores. Si acepta la premisa de que por cada Ocontenido hay “un” Onarrador, cuando propongamos que en “una” oferta (una novela, una película) “habla el personaje, luego el escritor” etc., estaremos hablando de diferentes lugares donde se coloca “el” narrador de un Ocontenido. Aún cuando en una película nos parezca ver “claramente” que hablan diferentes personas, al es-cuchar, por ejemplo que el personaje que encarna Diane keaton dis-cute con el de Keanu Reeves, deberemos considerar que la “voz” que narra no es la de ninguno de ellos sino la perspectiva desde la cual se han “recogido” los testimonios.

44

Relato y Narración

Decir con determinación que un Onarrador “es” omnisciente puede ser linguocéntrico: sólo puede afirmar eso el relatador que le haya otorgado esa licencia (lo haya establecido como narradorE omnis-ciente)18: muchas personas ofrecen “esto es lo que el pueblo quiere” pero pocas consiguen que se les otorgue licencia de “perceptores omniscientes” del “clamor popular”.

Contacto para el ofrecimiento. Publicación, pack, medio.

El entorno en el cual un relatador hace contacto con el soporte, ter-mina de conformar los Ocontenidos al asignar valores a variables como el momento histórico, ciertas LAPs, etc. El modo en que se publicite o se llame la atención a los relatadores es parte de ese en-torno.

El packaging también integra las ofertas y a veces hasta “es” la ofer-ta, como en el caso de las golosinas del “amor”19. La publicación de-fine licencias importantes: como ofrecedores debemos procurar que un relatador entienda útil para sí mismo considerar nuestra propues-ta. No tenemos derecho “natural” a invadir el espacio sensorial de otros, lo adquirimos por solicitud, negociando.

Al entorno y al propio soporte por “medio” de los cuales un relata-dor se apropie de una oferta, es a lo que hemos estado intentando aludir con “medio de comunicación”, sólo que, de verlo de modo no linguocéntrico, deberíamos no considerar por ejemplo a los llama-dos “medios”, canales de inoculación.

18 Para ser estrictos, deberíamos decir “desde tal novela se pide licencia de narradorE omnisciente”.

19 Algunas golosinas no ofrecen dulces sino manifestaciones de cariño, avaladas por dibujos de corazones visibles en el envase: compruébelo ofreciéndolas a la persona equivocada.

45

Alejandro Guevara

46

La Muerte de la Lengua

La muerte de la lengua

El título de esta parte de la tríada puede sonarle catástrofe. Acuerdo con que lo sea en el sentido de las dimensiones de la oferta pero no en el de desastre: no estoy pidiéndole que se corte la lengua, lo cual no se vería bien si tratamos sobre herramientas para relatar u ofrecer mejor.

Mucho de lo que le ofreceré no ha sido "originado" por mí (ha sido más bien ofrecido profusamente), pero déjenme contárselo a mi modo, para evitar las lagunas en que considero que han caído algu-nos colegas (ya es suficiente con las mías).

"Matar a la lengua" titula lo que es más bien una propuesta de des-activación de lo que llamo "linguocentrismo": el modo en que hemos creído crear e intercambiar sentido, "enviándolo" desde un dispositivo inoculador (más prestigioso) a otro, receptor (menos prestigioso). Abreva de lo que en el siglo pasado se llamó logocen-

47

Alejandro Guevara

trismo20, y ambos resultan de un enorme complejo de inferioridad de la humanidad, que, para saberse valiosa ha necesitado encontrar al-go o alguien que fuese "inferior". Éste complejo que creo que ya es hora de superar, ha dado lugar al sexismo, al racismo, al egoísmo…

La "mitad más valiosa"

Para ayudarnos a echar luz, algunos de nuestros antecesores de oc-cidente, tuvieron el atino de nombrar a un sistema en el cual inter-vienen dispositivos de contacto, distinguiendo un representante de los que parecen penetrar, por sobre los que parecen recibir: la len-gua. De esta forma pusieron nombre al prejuicio aunque no pudie-ron verlo, y nosotros todavía no logramos hacerlo con claridad: se-guimos llamando alegremente al sistema de interpelación del mundo humano, lenguaje. Y a su estudio, lingüística. Y por decirlo así, so-breentendemos que fueron las palabras al sonar las que enseñaron al oído a entenderlas.

Pero ¿podemos decir seriamente que fue una palabra primigenia la que tomó la virginidad del oído para completarlo de saberes? ¿Y si la avidez por intervenir en el mundo impulsó a los oídos a diseñar-las? ¿No habrá sido el intercambio entre lenguas y oídos lo que dio lugar al fenómeno?

20 Varios filósofos se dedicaron al tema, por lo que si le interesa ahondar en logo-centrismo, encontrará material y referencias de bibliografía en internet. Busque también “falogocentrismo”.

48

La Muerte de la Lengua

El prejuicio fundacional del linguocentrismo está tan embebido en nuestro pensamiento que nos parece a todas luces “natural” entender que las palabras circulan desde las lenguas hacia los oídos. En rela-ción con la lengua dimos al oído el lugar “siniestro” que damos a: obscuridad, corto o hembra, entre otros. La “orejeada”, de llamarse así, hubiese sido el lado obscuro de la lengua, un receptáculo pasivo de palabras. Por eso mismo, ni la nombramos.

Claro está, la cuestión no es determinar qué órgano fue más valioso: sería como estudiar si en la génesis de la internet ha sido más rele-vante la posibilidad de subir que la de descargar. Mal hubiéramos hecho entonces en llamar (linguocéntricamente) a la internet, “subi-da”, o “up”.

Y ni que hablar de “down”!.

La lengua aislada es completamente inútil. Necesita de los sabores, o de los oídos para “ser”. ¿Podemos aseverar que el dulzor del azú-car fue anterior al sentido que lo degusta? ¿Y todo lo contrario? ¿Es pertinente postular que los Adanes buscaron a las manzanas antes que las manzanas los previesen a ellos21?

¿Por qué entonces llamamos sólo “lengua” a la interacción con pa-labras? ¿Y por qué siguiendo esa lógica consideramos que hay tex-tos - portadores y lectores - receptores?

La creencia de que el habla proviene de una “lengua” es la misma que sustenta que somos personas (del lat. per sonare). Pero estas vi-

21 Dado que los frutos prevén que serán alimento de quienes los transportarán para que sus semillas puedan germinar en mejores tierras.

49

Alejandro Guevara

siones son parciales del mismo modo que lo es otorgar a lo general un sexo (¿medio sexo?). Si incorpora a su paradigma la otra mitad, logrará una cosmovisión completa y le permitirá comprender mejor a su propio entorno y a los otros. El faltante de la persona es el “re-latador22”. Una nueva figura que espero que reconozca en usted mism@, para completarse y comprenderse como persona-relatador y como integrante de grupos de relatadores-personas.

La muerte de la lengua es sólo nominal, ese nombre debe dejar lu-gar a uno (mejor que “orejo-lenguaje”, o “interoidolenguación”) que haga honor al fenómeno.

La cuestión del envío

La creencia de que las palabras “se dirigen” a los oídos, dio lugar a un paradigma que le propongo revisar, es la concepción que rigió hasta hoy (2013), aunque creíamos pensar lo contrario, de que los humanos somos receptores, tal como los de radio o tv, que reprodu-cen imágenes idénticas estén donde estén, a partir de objetos sem-brados mediante Brodcasting, un método que consiste en esparcir por doquier semillas en la tierra. De acuerdo con este concepto, en las mentes (recipientes) de los “receptores” podrán crecer mejores o peores plantas de esas semillas y algunas no germinar, no obstante todo lo que surja será dependiente genéticamente del "origen".

Pero si observa detenidamente, notará que los humanos buscamos sentido revisando entre la oferta de contenidos disponible y si no lo encontramos allí, lo creamos. Luego, con lo que se nos ofrece hacemos tanto un árbol como una flor, una casa, y hasta algo que a los “sembradores” jamás se les hubiese ocurrido. No puede haber enunciados como semillas, porque no puede esperarse que germine

22 Definición más completa en “Relatador_Persona”, página 65.

50

La Muerte de la Lengua

el mismo tipo de planta, ni siquiera con deformaciones, sino cual-quier cosa, de cualquier naturaleza. O nada. El contenido Incluso puede ser sólo disparador o la excusa para concluir algo que ya habitaba en la mente del “relatador” (a quien hasta ahora conside-ramos erróneamente receptor).

Los contenidos son instructivos ofrecidos, no “hechos” o elementos “dados”: las instrucciones para hacer un origami no son un pájaro de papel, ni tampoco “transportan” el pájaro de un humano a otro (si se emociona relatando con una película, no es porque se le haya “enviado” una emoción). Y a diferencia del instructivo para el ori-gami, los contenidos ofrecidos ni siquiera pueden aspirar a que quien aplique la receta encuentre idénticos materiales, ya que no hay dos humanos idénticos y ni siquiera un “mismo” humano es el mismo en diferente momento.

Intento ofrecerle que relatar no se trata de traficar pájaros sino de in-tercambiar instrucciones para volar.

La filosofía del envío es responsable de muchos contrasentidos. A modo de ejemplo, vea que, de acuerdo con como miramos hasta ahora, suele darse esta situación:

- ¿Has leído el libro sagrado?

- Sí, es excelente,

- Yo también lo veo así.

Luego se dedican, el uno a amar a unos y a otros, y el otro a asesinar a quienes ahora considera “impuros”. Y ambos creyendo responder a “lo mismo”.

51

Alejandro Guevara

Cambiar de paradigma coloca menos responsabilidad en los conte-nidos y más en los humanos.

No digo que el diálogo no pueda darse en el futuro, sino que ahora mismo, cuando decimos “leer libros” hablamos de “celebrar rela-tos”. La acción de leer libros debe definirse como la de reproducir DVDs: propiciar la exposición a un instructivo sin considerar qué se haga con eso. Puede haberse estado todo el tiempo frente a un libro como frente a una pantalla y no obstante, no haber celebrado nada.

Podremos entonces decir que dos personas leen “un mismo libro”, pero no que celebran un mismo relato.

Si por el contrario, se define a la acción de leer como el acto en el que interviene cada “lector” de modo que acontecerá un nuevo “tex-to” con cada “lectura”, se excluye la posibilidad de decir que dos personas leyeron “el mismo texto”.

Creer que se está enviando algo “hecho” para ser aprehendido es llevar el narcisismo al extremo. Es diferente pensar que ofrecemos algo que no podemos asir completamente, y que las habilidades de otros les permitirán celebrar relatos mejores aún que los propuestos, despejando paja de trigo, y descubriendo habilidades y debilidades ocultas hasta para nosotros mismos.

Por supuesto, esto vale para esta misma oferta.

No obstante, verlo así no indica que todo sea caótico o aleatorio. Existen negociaciones entre “ofrecedores” y “relatadores” que per-miten establecer cierto tipo de acuerdos para lograr unas certezas.

52

La Muerte de la Lengua

Las agrupo en lo que llamo “LAPs23” y son las responsables de que haya algún orden… y también algún desorden.