AbrahamLincoln 1809–1865AbrahamLincoln 1809–1865 TheBeginning...

Transcript of AbrahamLincoln 1809–1865AbrahamLincoln 1809–1865 TheBeginning...

Abraham Lincoln1809–1865

The Beginning

Abraham Lincoln never looked back on his childhoodwith much pleasure. He grew up poor on the westernfrontier, first in Kentucky and then in Indiana. YoungAbraham—he hated being called Abe—had enoughschooling to learn the basics of reading and arithmetic.From then on, he taught himself by reading any bookhe could find, memorizing long passages.

His mother died when he was nine. Following herdeath, Abraham’s father married a widow with threechildren. Sarah Lincoln brought order to the familyalong with unfamiliar comfort—good furniture, knivesand forks, linens for the beds. She insisted on a realfloor for the log cabin, a window to bring in light, asleeping loft for the boys. She loved her bookishstepson, and he loved her in return. Things weredifferent with his father. Thomas Lincoln was anilliterate man who was working his hardest just to keepthe farm going and provide for his family. When hesaw his strong young son with his nose in a book, hefumed and called him lazy. Abraham hated farm workand resented his father’s demands. They had one

important thing in common—a deep feeling against slavery—but it was not enough to heal the divide. As soonas Abraham came of age, he left the family and moved to New Salem, Illinois, to begin life on his own.

People liked Abraham Lincoln. He was often seen entertaining big groups of his friends with funny stories, histall frame lifting him high above their heads. Around young women, though, Lincoln’s charm vanished, and hefroze. He worried that he would spend his life alone, but in New Salem he met and fell in love with AnnRutledge. When she died of typhoid, he slipped into a deep depression. All his life he suffered from bouts ofcrushing sadness. They were as much a part of him as his wit, intelligence, and ambition.

Lincoln earned his law degree in New Salem, and he was elected to the Illinois state legislature. By the time hewas in his mid-30s, he had married Mary Todd, welcomed their first son, and been elected to the U.S. House ofRepresentatives. He was out of office and practicing law in 1854 when the simmering issue of slavery boiledover with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. He believed that if slavery could be kept out of Kansas andthe other territories, it would eventually die out across the country, and he reentered politics with this goal. Hehelped start the Republican Party in Illinois, and when Senator Stephen A. Douglas ran for reelection in 1858,Lincoln ran against him. Douglas won, but the debates between the two men over slavery showed off Lincoln’sskills as a thinker and a speaker. People began to say he had promise as a national candidate despite hisawkward appearance and backcountry manners.

Life Stories

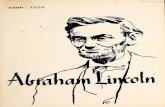

Mathew Brady, Abraham Lincoln, 1865. New-York HistoricalSociety Dept. of Prints and Photographs.

The Candidate

In the year before the 1860 presidential election, the front-runner for the Republican nomination was NewYork’s senator William H. Seward. But some New York Republicans, including Horace Greeley, the powerfuleditor of the New-York Tribune, worried that Seward’s intense antislavery views would scare away voters. Theywanted a candidate with a more moderate position on slavery and believed a westerner might win importantstates. The Lincoln-Douglas debates had introduced Lincoln’s views around the country—he did not wantslavery to spread into the new territories, but he did not object to its continuing where it already existed. Inother words, he was antislavery, but not an abolitionist. He was one of several politicians being closelyfollowed by Republican leaders in New York as they planned a lecture series to showcase men who mightunseat Seward.

At the time, a man who wanted to be president was quiet about it and did not campaign publicly. Lincolnadmitted only in private that “the taste is in my mouth a little.” He was working on his own behalf behind thescenes, hoping to be ready if Seward stumbled. When he received an invitation to deliver one of the New Yorklectures, he knew what an opportunity it was. He would be seen in the nation’s major city, heard by its leadingcitizens, and covered by the New York newspapers, the biggest of which were read all over the country. Hedecided to use the podium to confront squarely one of the central arguments of the proslavery movement: thatthe Founding Fathers had supported the spread of slavery into any new American lands. Lincoln spent weekspreparing a speech that would prove the opposite. He researched each of the signers of the Constitution atlength and wrote a speech to show that nearly all had at one time or another approved of limiting the spread ofslavery.

Lincoln left Springfield for New York on February 22, 1860, to deliver his speech. He borrowed Mary’s trunk,which he packed himself, cramming in the new black suit he had ordered for the occasion. On the 25th ofFebruary, he arrived in New York City and discovered that the location of his speech had been changed. Itwould not be in a Brooklyn antislavery church, but at the Cooper Union, a major hall in Manhattan. He spentthe next days revising his speech for the different audience and larger space. And on the 27th, after a morningstop at the Mathew Brady studio to have his photograph taken, he made his nearly two-hour speech before alarge audience. Greeley’s newspaper, the New-York Tribune, praised the speech lavishly. But many voters inNew York City, a Democratic stronghold, may have agreed more with the New-York Herald, which called thespeech “unmitigated trash.”

A few hundred people heard Lincoln’s speech in person. Thousands read it later, either in newspapers orpamphlets. Along with Brady’s stunning portrait, the Cooper Union lecture did what Lincoln and his supportershoped: it enhanced his stature as a thoughtful leader and gave him more momentum than the other contenders.Doubts about Seward continued to grow, and at the party convention Lincoln emerged as the Republicannominee for president. The Democratic Party, in the meantime, was in crisis. At its convention, it split over theprotection of slavery in the western territories, and Southerners nominated their own candidate, the incumbentvice president John Breckinridge. The Northern Democrats nominated Lincoln’s old Illinois antagonist,Stephen Douglas. Many in the border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri) hopedfor a compromise and nominated John Bell on a new Constitutional Union ticket. With his opposition split, onNovember 6, 1860, the Republican Lincoln was elected president. He carried New York State, but he lostheavily in New York City and its surrounding counties. On the national level, over 60 percent of the vote hadgone against him. Almost immediately, seven Southern states began the process of secession, as they hadthreatened to do if the antislavery Lincoln prevailed.

Life Stories

The President

The Civil War began within six weeks of Lincoln’s inauguration. Some people argued that the South should beallowed to leave the Union without a battle. But Lincoln believed that if states could secede at will, the nationwould eventually disintegrate and the entire American experiment in democracy would be at an end. He wasdetermined not to let this happen, and all his political decisions were focused on keeping the nation whole.During a single week in September 1862, he took two bold steps toward that goal, with enormousconsequences.

For most of his life, Lincoln reflected the common racial attitudes of his day and believed black people wereinferior to whites. But he was more antislavery than most of his countrymen. “If slavery is not wrong,” he oncesaid, “nothing is wrong.” Yet at the beginning of the war, he resisted abolitionists’ demands that he endAmerican slavery by a presidential edict. He was worried that it would erode support for the war, a politicalgamble he could not afford. Many Northerners, he knew, would fight to maintain the Union, but not to free theslaves. Lincoln needed those white men to continue to volunteer for the army, even as the war proved harder,longer, and bloodier than anyone had expected.

But abolitionists kept up the pressure. In the summer of 1862, when a New-York Tribune editorial begged foremancipation, Lincoln responded as a pragmatist: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I woulddo it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some andleaving others alone I would also do that.”

When Lincoln made this comment, he had already drafted his first version of the Emancipation Proclamation,though it was not yet public. It would free the slaves in states still in rebellion, and permit black men to jointhe Union army. He was honoring his own deepest feelings, but in making this decision at this time, he wasalso making an astute political move. Emancipation would damage the South’s economy, and black soldierswould dramatically boost the army’s size, adding men who were more committed than anyone to defeating theConfederacy. The president kept this Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation secret for a few weeks, waitingfor a Union victory so he could release it when the Union position looked strong. On September 22, 1862, afterthe army’s success at Antietam, he made the proclamation public. He was convinced it would help the Unionwin the war, and he was right.

Two days later, Lincoln issued the Proclamation Suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus, which outlawedsubversive criticism of the government and denied the right of habeas corpus to those arrested. In a time ofrebellion and war, Lincoln considered antigovernment comments and protests to be disloyal, perhaps eventreasonous. They aided the enemy by persuading men not to enlist, or to desert once they were in uniform.Even some of his supporters accused him of trampling on civil liberties, ignoring the First Amendment,overriding the authority of the states, and behaving like a tyrant.

The following year, the effects of both proclamations would play out. At last, black men were recruited intomilitary regiments and went to war wearing Union blue. In New York City, people who protested the war werejailed in the grim Fort Lafayette in Brooklyn. In 1863, when the army arrested the former Ohio congressmanClement Vallandigham for encouraging resistance to the draft, a huge anti-Lincoln demonstration was held inUnion Square. Together, the Emancipation Proclamation and the national suspension of habeas corpus fueledthe hostility toward the president and his policies that erupted in the New York City draft riots in the summerof 1863.

Though no one knew it at the time, the Civil War was only at the halfway point.

Life Stories

The Martyr

At last, on April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union forces at Appomattox,all but ending the Civil War after four years and more than 600,000 deaths. In the North, people took to thestreets, wild with relief and victory. But just five days later, on April 14, Lincoln was shot in the head at closerange while he watched a play with his wife. His attacker, John Wilkes Booth, was a bitterly disappointedConfederate sympathizer who was later captured, tried, and executed. Lincoln lived through the night, thendied on Saturday morning, April 15. He was the first American president to be assassinated. Within hours,newspapers brought the grim story to their readers. The news would have been shocking at any time, but itcame so soon after the war’s end that emotions swung sharply. In the North, uncontainable joy turned tooverwhelming grief. And in the South, the bitterness of defeat was briefly sweetened by rejoicing at the fall ofthe enemy’s leader, but many people recognized that Lincoln’s death was a calamity for North and South.

Lincoln had never been popular in New York, but within hours of his death, the entire city was deep inmourning. The attack had taken place on Good Friday, during Passover, and the timing prompted anoutpouring of feeling from the city’s churches and synagogues, where Lincoln was compared to Christ and toMoses. Following the funeral in Washington, D.C., the president’s body began a long journey back toSpringfield, Illinois, following the train route he had taken to his inauguration four years earlier. In cities andsmall towns along the way, Americans turned out to express their sadness and honor the president for the lasttime. The coffin arrived at the dock in New York City late in the morning of April 24. The following day,hundreds of thousands took part in the funeral procession as gun salutes were fired and the city’s churchbells rang.

Abraham Lincoln was a remarkable politician who has rarely been seen in ordinary light. During his time inoffice, he was thought by opponents (and even by some supporters) to be inept and dangerous. Today, he is themost admired of American presidents and a man much larger than life. This dramatic reappraisal took rootquickly in the months that followed the assassination, and it was led from New York City, the nation’spublishing center. For the two years after the president’s death, while the pain was fresh, the city’s writers,editors, and image-makers helped a willing public rethink the man who had led the nation through the CivilWar. He was routinely described in superlatives, and often in religious terms like martyr and savior. Even hisappearance was reconsidered. Long ridiculed as an ugly man, the remade Lincoln was powerful, heroic, andalmost handsome. This is the image that has survived, and it was cast in enormous proportions in the LincolnMemorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Sources: David W. Blight, Race and Reunion (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001); Edwin G.Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press,1999); David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); Harold Holzer, Lincoln atCooper Union: The Speech that Made Abraham Lincoln President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004);Harold Holzer, Gabor S. Boritt, and Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the PopularPrint (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984); James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil WarEra (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Life Stories

Abraham Lincoln1809–1865

Note: This is a shorter version of the life story, meantfor elementary school.

Abraham Lincoln was the president of the UnitedStates from 1861 to 1865. Many people believe he isthe best president in the country’s history.

Presidents often come from rich families and the bestschools, but Abraham Lincoln grew up poor inKentucky. He lived in a log cabin, the kind of housefamilies built for themselves after cutting down theirown trees. They made the houses no bigger thanabsolutely necessary—just a single room, with a dirtfloor and no windows. Lincoln’s family moved toIndiana when he was seven, and they built another logcabin like the one they’d left behind.

At the time, Kentucky and Indiana were America’swestern frontier and just being settled. Many familiesthere lived as the Lincolns did, but the life did notappeal to young Abraham (he hated being called Abe).He was very tall and strong, and the only boy in thefamily, so his father expected him to work hard. He

resented it, and he resented his father. He wanted to make a better life for himself, and he knew he needed aneducation. He had only a few months of school, just enough to learn the basics. After that he taught himself byreading any book he could find. There were no special books for children then. So he read what adults read,and he especially liked poetry and fables.

He had no teachers to guide him. But after his mother died and his stepmother arrived in the family, sheencouraged him and let him read the books she had brought. (She also fixed up the cabin and made it muchmore comfortable.) Other books he borrowed from neighbors or friends, sometimes walking miles to do so. Hememorized long passages so he would remember the book even if he needed to return it. If a book was hard tounderstand, he would read a passage over and over, and put it in his own words until he knew for sure what theauthor was saying. He was teaching himself how to learn, building habits he would follow all his life. Hetaught himself law in this way and gave himself a profession that took him away from farm work forever.

The big issue of Lincoln’s day was slavery. In the Northern states, like New York and Massachusetts, it wasillegal. But in the Southern states, like South Carolina and Mississippi, it was an important and legal part oflife that white people did not want to give up. Over several years in the 1850s, there were constant argumentsbetween people who wanted to end slavery and those who wanted it to continue. The whole country wasnervous about what might happen if the arguments became an all-out fight.

Life Stories

Mathew Brady, Abraham Lincoln, 1865. New-York HistoricalSociety Dept. of Prints and Photographs.

The slave states were unhappy with Lincoln because he was against slavery. As soon as he was electedpresident, seven Southern states said they were seceding from the United States and forming their own country.Lincoln did not believe they had the right to do this, and the two sides went to war. It was called the Civil Warbecause it was a war between Americans and Americans, with no foreign power involved. It lasted four yearsand killed 600,000 men, a huge number. Nearly everyone in the country knew a soldier who had died or beeninjured, and many families lost fathers and brothers and sons.

In the middle of the war, Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed nearly all the slaves in theSouth. He did this partly because he believed slavery was wrong and partly because he knew that freed slaveswould join the army and help defeat the South. The war ended at last on April 9, 1865, with a victory for theNorth. It meant that the United States would not be split into two countries.

Just five days after the war ended, Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed by John Wilkes Booth, who wasbitterly disappointed about the South’s defeat. Lincoln left behind his wife, Mary, and two sons, Robert andTad. During the war, he had not been a popular president. Many people had been very angry with him foractions he took, or didn’t take, or took too slowly. But after he died, on top of all the deaths of soldiers in thewar, people grieved as if they had lost someone they knew and loved.

Sources: David W. Blight, Race and Reunion (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001); Edwin G.Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press,1999); David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); Harold Holzer, Lincoln atCooper Union: The Speech that Made Abraham Lincoln President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004);Harold Holzer, Gabor S. Boritt, and Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the PopularPrint (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984); James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil WarEra (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Life Stories

Mathew Brady1823–1896

The most famous American photographer of his time, Mathew Brady wasworking with cameras almost from the time they were invented, around1840. Artistic by nature, he was still in his teens when he attended a classin New York City about the new daguerreotype (da-GARE-o-type)process. Before long, he opened his own studio in the city. Thedaguerreotype camera produced a one-of-a-kind original photograph—notan artist’s version of reality, but a genuine likeness that was surprisinglyclear and very beautiful. People had never seen anything like it, and theylined up wherever there was a camera and someone who could operate it.

Over the next few years, the daguerreotype was mostly replaced by the“wet collodion” process, which produced a negative that could be printedany number of times. Photography as we know it today was born, andpublic enthusiasm only increased, along with the number of people callingthemselves photographers. So Brady had many competitors, but he was a

good artist, especially skilled at composition and the fine touching up that made a subject look younger ormore attractive. His studio space was well appointed and well lit, and his equipment was sophisticated. He wasalso a first-rate businessman. This combination made him a standout among photographers. By the late 1850s,he had opened a second studio in Washington, D.C. Between his two locations his studio photographed untoldnumbers of politicians, including several presidents, as well as actors, painters, and European royalty. If youwere important, or hoped to be, you wanted Brady to take your picture.

The man who entered Brady’s New York studio on the morning of February 27, 1860, was already famous andabout to be more so. But as a photographic subject, Abraham Lincoln presented Brady with real challenges.Lincoln was remarkably tall and awkward-looking. His face was lined and craggy and scattered with warts andmoles. His hair was unruly. When his right eye focused, his left eye wandered off. His chest was too small, hisears and Adam’s apple too big. And he was wearing a suit that no prominent New Yorker would have beenseen in, ever. Not only was it too short in the sleeves and pant legs, it was badly wrinkled. City people calledLincoln a country bumpkin, and on this morning he looked it.

Brady led Lincoln upstairs to the sitting room and went to work. He decided against the usual head-and-shoulders pose and instead positioned the camera at a distance to show his subject from head to foot. Heunbuttoned Lincoln’s jacket to make his chest appear fuller. He brushed Lincoln’s hair into place so it neatlycovered the top of his large ears. Brady ordered a pillar—a studio prop—placed in the background and booksstacked on a short table so Lincoln could comfortably rest his fingertips on them. Brady looked through theshutter and then asked Lincoln if he might arrange his collar for him. Lincoln pulled his collar up himself,saying, “Ah. I see you want to shorten my neck.” “That’s just it,” Brady answered, and the two men laughed.Then Brady told Lincoln to look directly at the camera, and he signaled to the camera operator, who clickedthe shutter.

Life Stories

Unknown artist [U.S. Army SignalCorps], Portrait of Mathew B. Brady, ca.1861-65. New-York Historical Society.

Later, Brady delicately touched up the photograph to correct the wandering eye, tone down the warts andmoles, and fill in the deepest wrinkles in the future president’s face and wardrobe. He made several versions ofthe print, including one that ends below Lincoln’s hands and another that shows just his head and shoulders. Aswith all of his photographs, he made these versions available to lithographers and painters who wished to usethem as models for their work. Perhaps he knew immediately he had created a work of art, a photograph thatcaptured what people would increasingly see in the real Lincoln: intelligence, confidence, strength, andresolve.

Over the next five years, several portraits of Lincoln were taken in Brady’s studio. Some were taken by Bradyhimself, and others were taken by photographers he employed, including Alexander Gardner. Brady sometimesdid the setup while an assistant worked the camera, but any photograph taken in or purchased by Brady’sstudio was labeled “Photo by Brady.” Using a studio label was common practice at the time. It was notconsidered unethical, but it makes it difficult to know whether a particular photo was taken by Brady or byanother photographer. Brady’s studio is perhaps best known today for its Civil War photographs. Many ofthese, however, including the dramatic images of the battle of Gettysburg, were actually taken by Gardner andTimothy O’Sullivan, who oversaw Brady’s Washington, D.C., studio.

Sources: Charles Hamilton and Lloyd Ostendorf, Lincoln in Photographs: An Album of Every Known Pose(Dayton, O.: Morningside House, Inc., 1985); Harold Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech that MadeAbraham Lincoln President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004); James D. Horan, Mathew Brady:Historian with a Camera (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1955); Dorothy Meserve Kunhardt and Philip B.Kunhardt, Jr., Mathew Brady and His World, (New York: Time-Life Books, 1977).

Life Stories

Grace Bedell1848–1936

Grace Bedell was eleven years old in the early fall of 1860, andit may have been a lonely time for her. Just a few weeks earlier,when the summer began, she had been living with her family in

Albion, New York, the town where she had spent her whole life. Now they were 120 miles away, living inWestfield, New York, a small village on Lake Erie. There were many children in her new neighborhood,including girls her age, but she didn’t know them well yet. And in her family, no one was her age. Her sisterEllen was twenty, Alice was seventeen, her brother Fred was eight, and Eunice was just a baby. She had manygrown-up brothers, but they hadn’t moved to Westfield. Her big family suddenly seemed small.

In this town, politics mattered, and people did not always agree. Grace’s father, Norman Bedell, was a Lincolnman through and through. But some of his neighbors wanted the next president to be William Seward, who hadlived in Westfield about twenty years earlier and who spoke out loud and clear against slavery. In Westfield,where everyone knew there were people in town helping fugitive slaves escape to Canada, this was important.Some people were afraid that Lincoln would not fight hard enough to end slavery. They thought he was just abig, awkward nobody from out west, and they laughed at his homeliness.

There had been arguments about politics in the family, too. Some of Grace’s brothers were Republicans, andsome were Democrats who worried that there would be a civil war if the Republicans won. But her father wasgoing to vote for Lincoln, and if she had been old enough, and a man, Grace would have voted for Lincoln,too. At home and around town, she rooted for him, and she was annoyed when people made fun of his looks.But one day, in October 1860, Grace’s father came home with a campaign poster that showed pictures ofLincoln and the man he had chosen as his running mate, Hannibal Hamlin. Grace stared at the face of her hero,and she had to admit she was disappointed. She kept wondering what he could do to improve his appearance,and she finally decided he would look much better with a beard. She decided to send him a letter and tell himso. She wrote it in her clearest, best handwriting, and she addressed the envelope to “Hon. Abraham Lincoln,Springfield, Illinois.”

She never expected him to answer, but he did. In fact, he must have written his answer right after her letterarrived. He greeted her warmly and talked about his family, but he said that growing whiskers wasn’t for him.He thought it would look like he was just trying to impress people. He signed himself “Your very sincere wellwisher, A. Lincoln.”

For an eleven-year-old girl to receive a letter from Abraham Lincoln was shocking enough, but another shockwas still to come. In February 1861—four months after Grace had sent her letter—Lincoln took a slow trainride from Springfield toward Washington, D.C., for his inauguration. He stopped at cities and towns all alongthe way, and crowds stood along the tracks and cheered. One of his stops was Westfield, and Grace was in thecrowd with her two older sisters. But there were so many people, and so much noise, she couldn’t see Mr.Lincoln or hear what he said. She didn’t know he was telling the crowd he had exchanged letters with someonefrom their town and would like to meet her. The people yelled, “Who was it?” “What’s the name?” Mr. Lincolnanswered, “Grace Bedell.”

Life Stories

Grace Bedell to Abraham Lincoln, Oct. 15, 1860.Burton Historical Society, Detroit Public Library.

Suddenly Grace heard the crowd chanting her name, and people were looking at her and applauding. A mancame and led her toward the back of the train, where Mr. Lincoln stood. When she reached him, she saw a manwith a full beard. “You see, I let these whiskers grow for you, Grace,” he said, and he leaned down and kissedher. Then the train pulled away and she ran all the way home to tell her mother what had happened, stillholding the little bunch of winter roses she had hoped to give him if she’d gotten close enough, but hadforgotten.

Grace’s family stayed in Westfield for two years. They were back in Albion in January 1864 when Grace wasmoved to write another letter to Lincoln. This one was on a much more serious subject than whiskers. Shebegan by reminding the president about their earlier letters, and then she asked for his help. She said her fatherhad lost nearly all his property, and she was hoping Mr. Lincoln would help her find work in Washington soshe could help support her parents. She had heard that the Treasury Department was hiring women. Sheadmitted her family did not know she was writing this letter. She mentioned she had grown to the size of awoman, but she did not say she was fifteen years old, although the president would have known this if hestopped to think about it. This time, he did not respond.

Sources: David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); William J. Switala,Underground Railroad in New Jersey and New York (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2006); AbrahamLincoln to Grace Bedell, October 19, 1860, on loan from the Benjamin Shapell Family Manuscript Foundation,Library of Congress; Grace Bedell to Abraham Lincoln, October 15, 1860, Burton Historical Society, DetroitPublic Library; Grace Bedell to J. E. Boos, May 8, 1918, on loan from a private collector, Library of Congress.

Life Stories

Horatio Seymour1810–1886

Throughout his life, Horatio Seymour was an upstate New Yorker and aDemocrat. He practiced law in Albany as a young man, and he belongedto the conservative wing of the Democratic Party, which supported theextension of slavery into the new territories won in the MexicanAmerican War. This was a popular position in the late 1840s, and ithelped Seymour become governor of New York in 1852. Two years later,as antislavery sentiment was gaining ground in the state, he was voted outof office in a Republican sweep. He remained active in state politics andcampaigned for Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 presidential race, but hewatched his state vote for Lincoln.

When the Civil War began, Seymour was out of office, but he was viewedas the leader of the Democratic Party in New York State. So it wassignificant when he allied himself with the War Democrats, the branch ofthe party that cautiously supported the war. He did not support theLincoln administration, though. He thought it was much too extreme onimportant issues—it seized too much power for the federal government,favored emancipation, and curtailed civil liberties. Seymour believed that

his misgivings were dramatically borne out in September of 1862, when Lincoln issued the PreliminaryEmancipation Proclamation and the Proclamation Suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus just two days apart.One would free the slaves, and the other would squelch freedom of speech.

Seymour bitterly opposed both presidential edicts, and he also opposed the Lincoln administration’s plan toinstitute a draft that would force men to serve in the army. He believed the federal government had no legalright to take these actions. Giving voice to the deepest racism of his time, he called emancipation “a proposalfor the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, and of arson and murder.”

Many in New York State agreed with Seymour, and the Republicans lost badly in the elections that came justweeks later, on November 4, 1862. Ten years after his first election, Seymour was swept back into thegovernor’s office, a crushing blow to Lincoln, who had won the state in 1860. One of Lincoln’s Senate alliessaid it was worse than the bloodiest loss on any battlefield, because New York was the richest and mostpopulous state in the Union. “Most populous” meant the greatest number of potential soldiers for the war. Therecruitment effort was a state-by-state process, with each state assigned a quota, and an unfriendly New Yorkgovernor could interfere with what Lincoln needed most: Union men on the battlefield.

Lincoln’s political base of support had been thin from the start. Now he hoped to form an alliance betweenRepublicans and War Democrats, and he did his best to win over Seymour. He wrote letters that appealed toSeymour’s own presidential ambitions, and he emphasized their shared desire to preserve the Union. ButSeymour made Lincoln’s work difficult. He stonewalled efforts to form a regiment of black soldiers from NewYork State, even though it would have helped him meet the state quota. He maintained his stance that New

Life Stories

Brady National Portrait Gallery,Horatio Seymour, ca. 1855-1865.New-York Historical Society Dept. ofPrints and Photographs.

York’s quota was disproportionately high. And he continued to rail against plans for the draft, which hethought was unconstitutional, and which he knew would target poor people and immigrants, groups thatsupported Democrats.

Lincoln’s hopes for winning Seymour to his side were dashed in May of 1863 with the arrest and sentencing ofthe former Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham for outspoken criticism of the war. Seymour rushed tothe support of his fellow Democrat, but like many, he was genuinely outraged by the case: “[It] involved aseries of offenses against our most sacred rights. It interfered with the freedom of speech; it violated our rightsto be secure in our homes against unreasonable searches and seizures; it pronounced sentence without trial,save one which was a mockery.”

Despite Seymour’s long opposition, the draft became law in March 1863. New York City’s lottery began onJuly 11, when the names of the first draftees were drawn and then published in the newspaper the followingday. Although the first hours were peaceful, the draft lottery soon prompted precisely the kind of violenceSeymour himself had predicted. For days, mobs of young men wrecked havoc in the city, protesting the draftand the war itself. They targeted African American people and locations in a fury over what they saw as thenew purpose of the war: freeing the slaves.

Many criticized Seymour for not rushing and doing everything he could to quiet the violence. When he didarrive and speak to the crowds, he asked for calm but agreed the draft was wrong and unfair and said he wouldcontinue to fight it. Some reports said he addressed the mobs as “My friends,” and later he was held partiallyresponsible for the destruction and loss of life in the riots, the worst in American history. After the violencesubsided, he continued to resist the draft, but in the end he allowed it to resume in New York City on August19. When he campaigned for another term in November, Republicans used his performance in the draft riotsagainst him, and he was voted out of office. One of his last acts as governor was to permit the formation of ablack regiment from New York State. He refused to run for president in 1864, but he was given a chance againin 1868, when he lost to Ulysses S. Grant.

Sources: Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics inthe Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990); David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (NewYork: Simon and Schuster, 1995); J. G. Nicolay and John Hay, “Abraham Lincoln: A History. Vallandigham,”The Century: A Popular Quarterly 38, no. 1 (May 1889), http://digital.library.cornell.edu, Making of Americacollection, accessed 7/20/09 by M. Waters; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era(New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Barnet Schecter, The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riotsand the Fight to Reconstruct America (New York: Walker and Company, 2005).

Life Stories

Frederick Douglass1818–1895

When he was a young boy, Frederick Douglass’s name was FrederickBailey. He lived with his grandparents, and he probably didn’t think ofhimself as a slave. He had his first taste of the life that lay before him whenhe was six years old and began to work in his owner’s house on aplantation near Easton, Maryland. With some help from a young whitemistress, he learned to read a bit, and later he taught himself more—insecret, since slaves were not allowed to have reading skills.

Given his early experiences, and probably his personality, he didn’t seehimself as a slave, and he didn’t behave like one. By the time he was ateenager, he was considered hard to handle. His frustrated owner sent himto work as a field hand for Edward Covey, who was known as a “slavebreaker.” Covey hit him every day, and Frederick could feel his spirit beingcrushed. One day, when Covey began to beat him severely, he decided hehad had enough and fought back against his master, who was smaller. Aftertwo hours, Covey gave up, claiming a victory he hadn’t won. For Frederick,it was a turning point. From then on he felt defiant, not afraid. Four yearslater, when he was twenty, he put on a sailor’s uniform, tucked the papers

of a free black seaman into his pocket, and began his escape. His disguise carried him to freedom in the North,and then he disguised himself further by calling himself Frederick Douglass.

Douglass worked as a ship’s caulker in New Bedford, Massachusetts, but his real profession was as anantislavery activist. He began to speak out at abolition meetings, sometimes describing his own experiences.White people who heard him were astounded. Not only was he tall and imposing, but he was also far moreeloquent than they expected. Some didn’t believe he could ever have been enslaved, and others suggested thathe not speak so well, that he try to sound more like a slave. He was so furious that he sat down and wrote hisautobiography, which people all over the United States and Europe read. By the time he was thirty, he hadbecome the most famous black person in the world.

Some prominent abolitionists thought slavery would end voluntarily if people realized how morally wrong itwas, so they worked hard to convince them. Douglass came to feel that slavery would end only if it were madeillegal, and this required laws and politicians. “I . . . believe the way to abolish slavery in America is to votesuch men into power as will use their power for the Abolition of slavery.” He supported the newly formedRepublican Party because of its antislavery platform. And he was cheered when he read about the debatesbetween Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas in Illinois in 1858. Lincoln said the nation wouldnot be able to survive half slave and half free; that it would become all one thing or all the other. Douglassagreed, and he believed that after the Compromise of 1850, the Dred Scott decision, and the Kansas-NebraskaAct, the country was moving in the direction of all-slave. He respected Lincoln for saying this clearly andpublicly. He thought it would persuade many more people to join the fight against slavery.

Lincoln and Douglass followed each other’s speeches and writings closely, but they did not meet in personuntil August 1863. By then Lincoln was president, the country was at war, and a disappointed Douglass was

Life Stories

Unknown artist, Frederick Douglass.New-York Historical Society Dept. ofPrints and Photographs.

angry with the man he had once admired. He thought the Lincoln administration had been much too slow withemancipation, and he was unhappy about the way black soldiers were being treated. He decided to go and talkwith the president in person. Lincoln welcomed Douglass, though he was feeling defensive. He knew Douglasshad a low opinion of him just then. He spoke of the need to “talk up” the country before taking bold steps. Buthe promised to keep his word, and Douglass left the meeting encouraged by Lincoln’s commitment toantislavery and impressed by the president’s treatment of him. “I was never in any way reminded of myhumble origin, or of my unpopular color.” In black men’s exchanges with whites, this was rare indeed.

The two men met twice more. In August 1864, Lincoln asked Douglass to come to the White House as hefaced reelection, knowing he was almost certain to lose given how badly the war was going. He was beingpressured to negotiate with the Confederacy and even to revoke the Emancipation Proclamation—anything toend the war. Douglass advised the president to hold firm. The two men talked for hours, working out a daringplan to draw Southern slaves into the Union army. By the end of their meeting, each saw the other as a friendand ally. The following March, after military successes had won Lincoln a second term, Douglass was invitedto hear the second inaugural address, in which Lincoln argued for forgiveness toward the South, for “malicetoward none.” At the reception afterward, Lincoln took Douglass by the hand and asked him what he hadthought of the speech, adding, “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.”Douglass pronounced it “a sacred effort,” and he meant it.

A month later, Douglass was at home in Rochester, New York, when he received word of Lincoln’sassassination. It was, he said, a “personal as well as a national calamity.” In impromptu words addressed toshocked mourners gathered at City Hall, he spoke of Lincoln as America’s Christ, whose blood “will be thesalvation of our country.” He continued to see Lincoln as the nation’s savior, believing that “the hour and theman of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln.” Over time, Douglass came tothink Lincoln had been right when he put reuniting the country ahead of freeing the slaves, and he praised thepresident’s political genius. In 1876, when he gave the keynote address at the unveiling of the Freedman’sMonument in Washington, D.C., he said: “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemedtardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was boundas a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

After the war, many African American people struggled with their personal memories of slavery, and they triedto close the door on their painful past. Douglass felt this was a dangerous tendency. He believed black peoplecould not afford to put their experiences behind them: their memories were too powerful a legacy to ignore.

Sources: David W. Blight, Race and Reunion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); David HerbertDonald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of FrederickDouglass, an American Slave (New York: Literary Classics, 1994); John Stauffer, Giants: The Parallel Lives ofFrederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln (New York: Twelve, Hachette Book Group, 2008).

Life Stories

Clement Vallandigham1820–1871

Clement Vallandigham (Va-LAN-dig-um) had been elected to Congressfrom Ohio. Like Abraham Lincoln, he was a westerner and a powerfulspeaker, but otherwise the two men had little in common. As a staunchDemocrat, Vallandigham believed in states’ rights and opposed abolition.His arguments and his fiery speaking style appealed to poor farmers whohad moved to Ohio from the South and to Irish and German immigrants.By 1860, he was a leader of the national Democratic Party and of thebranch of the party known as Peace Democrats, who argued for anegotiated settlement with the South.

When war came, Vallandigham remained loyal to the Union, but heattacked the president repeatedly. In mid-January 1863, just two weeksafter the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, he reminded hisaudience that he had opposed the war from the start. “I was satisfied . . .that the secret but real purpose of the war was to abolish slavery in thestates, . . . and with it . . . the change of our present democratical form ofgovernment into an imperial despotism. . . . Our Southern brethren were tobe whipped back into love and fellowship at the point of a bayonet. Oh,monstrous delusion!”

The spring of 1863 was a risky time for the Union. The army was losing many battles, and the leadershiplooked inept. The bold Confederate general Robert E. Lee was known to be planning an invasion of the North.There was public outrage when the Emancipation Proclamation seemed to make freeing the slaves the newgoal of the war, and more outrage over the recent draft law, which would force men to serve in the army forthe first time. In western states there was talk of seceding from the Union. Lincoln’s shaky alliance—Republicans, Democrats, abolitionists, immigrants, manufacturers, eastern businessmen, and prairiefarmers—looked ready to crack.

The Democrats, and especially Vallandigham, kept up the pressure. General Ambrose Burnside, whom Lincolnhad put in charge of keeping the western states within the Union, reacted to what he viewed as treasonousattacks on the federal government. Taking the lead from Lincoln’s Proclamation Suspending the Writ ofHabeas Corpus, on April 13 he issued a general order: anyone who helped or declared sympathy for the enemywould be arrested and tried as a traitor. The order affected the large area under Burnside’s control: Ohio,Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Kentucky.

Vallandigham, at the time one of the best-known Democrats in the nation though no longer a congressman,decided to test Burnside’s order with even hotter rhetoric than usual. At a series of public talks, he bluntlycriticized the government, declared his support for the South, claimed the war was being fought to enslavewhites and free blacks, railed against anyone weak enough to allow himself to be drafted, and called on votersto overthrow the tyrant he called “King Lincoln.” Burnside sent an undercover agent to get a written record ofthe speeches, and at dawn on May 5, 1863, he sent soldiers to Vallandigham’s home to arrest him. The next

Life Stories

W.G. Jackman, C.S. Vallandigham.New-York Historical Society Dept. ofPrints and Photographs.

day a military tribunal tried and convicted him of violating the law that prohibited public criticism of thegovernment. His lawyer appealed for a writ of habeas corpus—which might have freed the prisoner with achallenge to the military court’s authority—but was denied. He was sentenced to prison in a fort in BostonHarbor.

Democrats were furious, and even some Republicans accused Lincoln of trampling on free speech. Many in thepresident’s cabinet felt the arrest had been unnecessary. Lincoln seemed surprised by the whole event, thoughhe had drafted the original proclamation himself and had approved Burnside’s general order. Now he was in adangerous position: he could support Burnside and the tribunal’s decision, or he could annul the sentence ofthe court. Supporting his commander would fuel the public outcry. Annulling the sentence would undercutBurnside’s authority and increase secession fever in the west. The Union loss at Chancellorsville, where itsforces vastly outnumbered Confederate forces, did not make the president’s decision easier. In mid-May,Lincoln chose to support Burnside, but he modified the military court’s sentence: rather than serving time inprison in a Union fortress, the accused would be turned over to the Confederates for the remainder of the war.

The Vallandigham case caused a national uproar that was not quieted by Lincoln’s actions. In the South it wasseen as proof of a growing insurgency in the North. On the Union side, it further undercut support for the warand the president. Lincoln wanted an opportunity to address the matter again. His chance came when a groupof New York State Democrats, led by the upstate businessman Erastus Corning, met to adopt a set ofresolutions condemning the treatment of Vallandigham. Fortunately for Lincoln, the resolutions looked likestraightforward party politics: the men who drafted them were not prominent, did not support the Union cause,and voiced praise for New York’s Democratic governor, Horatio Seymour.

Lincoln wrote his response on June 12. He said that in normal times, the actions taken against Vallandighamwould have violated his civil rights, but this was a time of rebellion and war. The Constitution gave thepresident authority to suspend liberties if public safety requires it, so he had not overstepped his role. Further,he said, Vallandigham was not arrested because he disagreed with the government’s policies, but because hewas damaging the army. “Long experience has shown that armies cannot be maintained unless desertion shallbe punished by the severe penalty of death. . . . Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while Imust not touch a hair of a wily agitator who induces him to desert? This is none the less injurious wheneffected by getting a father, or brother, or friend into a public meeting, and there working upon his feelingsuntil he is persuaded to write the soldier boy that he is fighting in a bad cause, for a wicked Administration ofa contemptible Government, too weak to arrest and punish him if he shall desert. I think that in such a case tosilence the agitator and to save the boy is not only constitutional, but, withal, a great mercy.”

Lincoln’s response was published in the New-York Tribune and later in pamphlet form, and it had the effectLincoln hoped. Unionists were relieved to see the president’s convincing argument. Vallandigham, whoescaped to Canada in July, went down in history not as a great hero of civil liberties, but as a “wily agitator.”He returned to the United States a few months later and openly resumed his thunderous speeches, but Lincolnignored him.

Sources: David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995); J. G. Nicolay and John Hay,“Abraham Lincoln: A History. Vallandigham,” The Century: A Popular Quarterly 38, no. 1 (May 1889),http://digital.library.cornell.edu, Making of America collection, accessed 8/4/09 by M. Waters; James M.McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Life Stories

Horace Greeley1811–1872

Horace Greeley dedicated his 1868 autobiography to“our American boys, who, born in poverty, cradled inobscurity and early called from school to rugged labor,are seeking to convert obstacle into opportunity andwrest achievement from difficulty.” He was honoringsoldiers who had fought on both sides of the Civil War,but his language says a great deal about what hevalued in them and in himself. Few poor boys everconverted obstacle to opportunity as well as HoraceGreeley. He grew up on hardscrabble New Englandfarms, often missed school for farm work, and beganhis apprenticeship to a printer when he was onlyfourteen. But he became the nation’s leading journalistand one of the most influential men of his time.

Greeley’s lifelong devotion to journalism and politicsbegan when he was in his early twenties. He joined theWhig party and started his own journal, which he used

to promote his preferred candidates for office. He was only thirty when he launched the New-York Tribune asNewYork’s first Whig paper in 1841. During the next twenty years, he helped start the Republican Party afterthe Whigs splintered over slavery, and the Tribune’s circulation grew to 300,000 people in NewYork andaround the country. At home in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln read the Tribune. Like other newspapersof its time, it was blunt about its political positions. No one expected a newspaper to be fair and unbiased.So in daily, weekly, and semiweekly editions, 300,000 people read Greeley’s ideas about the principle offreedom, which he valued above all else. His frequent attacks on the institution of slavery were part of thatlarger philosophy.

In 1856, the Republicans ran their first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, and lost. With the 1860election approaching, Greeley was determined not to see that happen again. Along with other prominent partymen, he was worried that the front-runner, William Seward, was too radical on slavery to appeal to the averageAmerican voter. Greeley served as an advisor to the Young Men’s Central Republican Union, which organized aNewYork lecture series to publicize strong candidates who might loosen Seward’s grip on the partynomination. Greeley’s first choice was the Missourian Edward Bates, but after Lincoln made his impressivespeech at Cooper Union in February 1860, Greeley supported him enthusiastically. In addressing why hethought Lincoln might win, the politically savvy Greeley wrote: “I want to succeed this time, yet I know thecountry is not Anti-Slavery. It will only swallow a little Anti-Slavery in a great deal of sweetening. An Anti-Slavery man per se cannot be elected; but a Tariff, River and Harbor, Pacific Railroad, Free Homestead manmay succeed although he is Anti-Slavery.”

After Lincoln’s inauguration and the outbreak of war, the role of the press became an issue for journalists andpoliticians alike. Greeley had always been free with his opinions, but he largely agreed that published criticismof the government would damage the war effort. In the fall of 1861, he reached a secret deal with the president

Life Stories

A.H. Ritchie, engraver, after photo by Mathew Brady,Horace Greeley. New-York Historical Society Dept. of Printsand Photographs.

that served the needs of both of them. Working through an intermediary on his staff, Lincoln would giveGreeley privileged information not released to other newspapers. In return, Greeley would not attack thepresident’s policy or his handling of the war. Lincoln commented, “having him firmly behind me will be ashelpful to me as an army of one hundred thousand men.”

Lincoln claimed to have the “utmost confidence” in Greeley, but their arrangement was uneasy. Greeley couldbe unpredictable, and Lincoln never entirely trusted him. A few months after their deal was made, Greeleywrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton saying he had the right to “denounce the whole administration” if itwould serve the public good. He meant it. After the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, he accused Union officers of“utter inefficiency and incompetency, if not downright treachery.” He continued to criticize the administrationin the Tribune with frequency.

From the beginning of the war, Greeley was eager for the president to use his legal right to end slavery. Hewaited for the edict he thought would come early in the Lincoln administration, and he was bitterlydisappointed when the months passed and no proclamation was issued. He pressured Lincoln in the pages ofthe Tribune and in personal meetings. In the summer of 1862, a frustrated and angry Greeley sent Lincoln aletter, which he published the next day in the newspaper under the headline “The Prayer of Twenty Millions.” Itwas a fierce call for emancipation in the name of all twenty million Northerners. Lincoln answered almostimmediately that his goal was to save the Union, and that he would do whatever he needed to do to achieve it:free all the slaves, free some, or free none. At the time, Lincoln had already drafted a preliminary emancipationproclamation, as Greeley learned hours after the prayer was published. But the president needed time beforemaking it public.

Despite his compromise on press freedom, Greeley believed that personal freedom of speech was a differentissue. He was alarmed when the Proclamation Suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus was issued and it beganto generate arrests of people for speaking their minds, but he held his tongue until the former Ohiocongressman Clement Vallandigham was pulled from his home and charged with treason. He agreed thatVallandigham’s political views were “as bad as bad can be,” but he felt that American law protected people’sfree speech no matter what was said. Greeley did not make a crusade out of the issue, however. And later, whenLincoln issued another proclamation suspending habeas corpus, Greeley praised him for acting “courageouslyand wisely.” He maintained this position for the remainder of the war.

Greeley had sat behind Lincoln as he delivered his first inaugural address, and he worried then that an assassinmight be lurking in the crowd. Still, he was as shocked as anyone four years later, just after the war ended,when the dreaded attack came. But he was still operating as a newsman, and he had just written an articlecritical of the president. He considered running his piece despite the news of the assassination, but hismanaging editor, Sidney Gray, refused to do so. Greeley reprimanded him, but the article did not run. Early on,Greeley saw the direction of public sentiment after the assassination, and he lamented “the extravagant andpreposterous laudations on our dead President as the wisest and greatest man who ever lived.” But he wassaddened himself by the loss of the man he had helped to bring to the presidency.

Sources: David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (NewYork: Simon and Schuster, 1995); Horace Greeley, Recollectionsof a Busy Life (NewYork: J. B Ford and Company, 1868), http://google.books.com, accessed 8/6/09 by M.Waters; Harold Holzer, Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech that Made Abraham Lincoln President (NewYork: Simon and Schuster, 2004); Robert C. Williams, Horace Greeley: Champion of American Freedom (NewYork: NewYork University Press, 2006).

Life Stories

Walt Whitman1819–1892

In the 1850s, Walt Whitman was not seen as a major American poet—yet.He had published two editions of his collection Leaves of Grass, which wasa tribute to New York City despite its rural-sounding title. But he made hisliving as a newspaperman. Like many young men who grew up poor, hehad finished elementary school and then been apprenticed to a printer.Given this training, journalism was a logical career choice. And given hiswriting skill, he had moved quickly from setting type to editing andreporting. New York City was the nation’s newspaper capital, publishingmore than 150 papers, large and small. Some, like the New-York Tribune,the New-York Herald, and the New-York Times, were powerful dailies thatwere read all over the country. Whitman concentrated on smaller journals,and he wrote for more than a dozen of them. He covered many topics, buthe especially loved anything related to street life in the city, which hecelebrated with exuberant, rapid-fire prose. He wanted all of his writing,including his poems, to sound like the world he was describing.

Whitman also tackled the political question that was threatening to rip thenation apart. His views on slavery were moderate. He saw it as evil, and inthe 1840s he founded a free-soil newspaper, the Brooklyn Freeman, to argue

against the spread of slavery to the territories. But he believed that runaway slaves should be returned to theirmasters because the law required it. In the late 1850s, as the pro- and antislavery forces became more extremeand more divided, he looked for a middle-of-the-road candidate who might be able to keep the nation fromwar. After briefly backing Stephen A. Douglas for president, he threw his support behind Abraham Lincoln. Hewas not present for Lincoln’s speech at Cooper Union in 1860, but he was in the crowd that turned out whenLincoln came to New York on his way to his inauguration. At other stops, the president-elect had been noisilywelcomed, but in New York, 30,000 to 40,000 people stood on the streets in dead silence: “not a voice—not asound,” Whitman wrote. This icy greeting served as a reminder that New York City was not in Lincoln’s camp.

At a time when poets and writers often came from America’s wealthiest families, Whitman was unusual, a poorboy without much formal education who wrote about the lives of ordinary men and women. He saw events—even dramatic, national events—from the perspective of the everyday people who lived through them. Thisnatural inclination became even more important to his poems and his life following a frightening experience inhis family. A week before Christmas 1862, the Whitmans read a newspaper list of soldiers who had beenwounded in battle. One of the names, they were sure, was a misspelling of George Whitman, the name of oneof Walt Whitman’s brothers. Within hours, Walt was on his way from New York to the army hospitals inWashington, D.C., to look for his injured brother.

After a desperate two-day search, Walt learned that George’s wound had been minor, and that he was still withhis regiment. Walt was able to travel to the battlefield in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and the two brothers spent afew days together. For Walt, it was a close-up view of war that he never forgot. He saw gruesome evidence ofthe terrible wounds the soldiers had suffered. He saw how young, scared, and lonely they were. And though he

Life Stories

“Walt Whitman, head-and-shouldersportrait, facing right, wearing hat,”1863. Library of Congress Prints andPhotographs Division.

had no medical training, he spent the remainder of the war visiting the wounded in Washington’s hospitals,offering sympathy and words of encouragement. He wrote a number of poems about the cost of war for thosewho fight it and for their families.

Whitman was in Brooklyn with his family when he read news of Lincoln’s assassination. He went across toManhattan and walked along Broadway in the rain, writing that everything was draped in black, even thewindows. He returned to Washington, D.C., three days after the president’s death, but he did not stand in lineto see the body lying in state, and he did not hear the funeral sermon. He turned to poetry to mark his grief. Hewrote “Hush’d Be the Camps To-day,” his first Lincoln poem. Not surprisingly, he focused on the feelings ofsoldiers who have lost “our dear commander.” Over the next months, Whitman wrote two other poems aboutLincoln. “O Captain! My Captain!” has rhyming lines, which set it apart from his other verse. It was the onlysuccess Whitman had during his lifetime, and he was asked to read it often. It seemed to capture Americans’simple and powerful reaction to the president’s death.

Whitman’s great masterpiece is his long elegy to Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In thewake of the assassination, newspapers reported that sprays of lilacs had surrounded Lincoln’s coffin, and lilacbushes were blooming in profusion all around Washington at the time of the funeral. For Whitman, theseflowers and the night sky in springtime were forever associated with his memories of the fallen president. InWhitman’s stately poem, Lincoln is not presented as a saint or a god. He is “the sweetest, wisest soul,” thenation’s stolen leader, and a better man than most, but a man. For grieving readers, he represented all thedeaths of this long and brutal war.

Sources: Sources: Gay Wilson Allen, The Solitary Singer: A Critical Biography of Walt Whitman (Chicago:University of Chicago Press, 1985; first published 1955); David W. Blight, Race and Reunion (Cambridge:Harvard University Press, 2001); Gregory Eiselein, “Lincoln’s Death,” The Walt Whitman Archive,http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_30.html, accessed 7/20/09 by M. Waters;Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A.Knopf, 2008); Walt Whitman: Complete Poetry and Collected Prose (New York: The Library of America, 1982).

Life Stories

Currier and Ives1857–1907

Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888) was about fifteen whenhe finished school and went out to learn a trade so hecould make a living. Many young men did the same,but Currier made a smart—or lucky—choice. Heapprenticed with the first American company tosuccessfully use the new technique of lithography,which was quicker and less expensive than oldermethods of printing images. Lithography was stillcatching on in America when Currier, just twenty-twoyears old, finished his apprenticeship and opened hisown firm in New York. He ran the company alone forseveral years, but in 1857 he made his bookkeeper,James Ives (1824–1895), his partner. The pictures

produced by their firm, Currier and Ives, would color how Americans saw themselves and their country for thenext fifty years, and many are still popular today.

Currier and Ives was a big operation, set up in an assembly line to produce images quickly. The process beganwith one of the firm’s artists making a drawing on paper. Then a lithographer transferred the drawing to a stonetile with a special crayon. The tile was then inked, and a printer carefully pressed a sheet of paper over the tileto pick up the image. This process could be repeated many times to produce many copies of the same picture.Currier and Ives employed a roomful of women to hand color each lithograph once the ink was dry, givingeach copy a touch of originality.

Currier and Ives were not the only lithographers in America, but they were the most successful. At one point,they printed 95 percent of all the lithographs in circulation in the United States. The prints sold for less thantwenty cents each and were easy to find in stores and catalogues, which contributed to their popularity. Onlyrich people could buy original paintings for their homes, but almost anyone could afford a lithograph. It didn’tmatter that relatives and neighbors might have the same pictures on their walls.

Another appeal of Currier and Ives was that they printed pictures on so many subjects—over 7,000 images inthe company’s lifetime. People who lived when Currier and Ives was at its peak could buy images of importantmoments they had only read about, from disasters to sporting events. And they could decorate their walls withpretty pictures that showed American life at its best. Real cities may have been increasingly dirty, crowded,and dangerous, but Currier and Ives showed them as sparkling places, brightened by moonlight or fresh snow.In their country landscapes, many of which are still popular today, the horses were sleek, houses werecomfortable and safe, and families were always having a wonderful time together. It was the America peoplewanted.

Currier and Ives also produced many prints about politics, especially during the Civil War. At the time, peoplefollowed politics the way they follow sports today. They went out of their way to hear a politician deliver aspeech, and they bought political prints in great numbers. Bringing these images into their homes gave people

Life Stories

Currier & Ives, The Battle of Antietam, Md. Sept. 17th, 1862, c.1862. Library of Congress.

a way to follow and remember high points, trigger discussions in the family, teach children about importantevents, and declare the political point of view that prevailed in the household.

In general, Currier and Ives supported the Union, the Republican Party, and the president, but they wantedpeople who disagreed to buy their prints, too. They usually showed Abraham Lincoln in a good light, hisimage based on Mathew Brady’s great photograph of February 1860, with a beard added after the presidentgrew whiskers. But Currier and Ives’s catalogue included cartoons in which Lincoln looked clumsy or crackedjokes at the wrong time, too. And for those at home with a father or son or husband fighting in the war, Currierand Ives provided a way to see what the battlefield was like without the terror and death shown in Brady’sphotos. They even dared to produce a lithograph of John Wilkes Booth shooting Abraham Lincoln in the headjust at the moment between the firing of the gun and the bullet’s hitting its mark. It became one of the best-selling prints in American history.

Sources: Bryan F. LeBeau, “The Mind of the North in Pictures: Currier and Ives’s Civil War,” Common-Place,January 2009, www.common-place.org, accessed 7/14/09 by M. Waters; Harold Holzer, Lincoln at CooperUnion: The Speech that Made Abraham Lincoln President (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004); HaroldHolzer, Gabor S. Boritt, and Mark E. Neeley, Jr., The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print(New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1984).

Life Stories