Objetivo de BD

62

BD HAI: Tus socios en la prevención y el control de la infección hospitalaria www.bd.com/hais

Transcript of Objetivo de BD

Objetivo de BD BD HAI: Tus socios en la prevención y el control de

la infección hospitalaria

www.bd.com/hais

ÍNDICE

1. MRSA: La amenaza oculta 2. MRSA: Situación actual 3. Control de MRSA:Vigilancia

Activa 4. Vigilancia de MRSA en UCI 5. El impacto de utilizar métodos

moleculares 6. BD GO. Rendimiento de la

prueba y publicaciones 7. Control de MRSA: Innovación:

RT-PCR + Tradición: cultivo

1. MRSA: La amenaza oculta

• Los pacientes infectados y colonizados constituyen un reservorio por igual para la transmisión nosocomial del MRSA.

• Más del 70% del reservorio son pacientes colonizados, solo detectados con sistemas de vigilancia activa.

• El 30-50% de los pacientes hospitalizados que sean portadores de MRSA pueden desarrollar una infección por MRSA.

• Las infecciones por MRSA están asociadas a una alta mortalidad.

Karchmer IDSA 2002, APIC 2005 Selgado SHEA 2003 Boyce et al., SHEA 1998 Perencevich APIC 2005

• La colonización por MRSA es asintomática.

• Los reservorios son normalmente la piel y las fosas nasales.

• La transmisión se produce generalmente de un paciente colonizado a otros, y a través de las manos del trabajador sanitario.

• Se transmite fácilmente y sin darnos cuenta. Colonizados

Pacientes asintomáticos

Boyce et al., SHEA 1998, Abstract S74. Zachary et al., ICHE (2001) 22:560-564. Boyce et al., ICHE (1997) 18:622.

Infecciones clínicas

MRSA: La amenaza oculta

• Se estima que aprox. 50.000 pacientes al año mueren por HAIs en Europa. Esto representa más de 150 por día. (EC Health and Consumer Directorate General)

• Una infección por MRSA prolonga la estancia en el hospital en una media de entre 4 y 14 días y el coste del tratamiento asociado oscila entre €10.000 y €36.000 por paciente. (Kim et al, 2001; Stone et al, 2002)

• La colonización por MRSA después de la admisión del paciente aumenta por diez el riesgo de sufrir una infección por MRSA durante su estancia en el hospital. (Davis et al. 2004)

• Se producen aproximadamente 3 millones de HAIS al año en Europa, afectando a 1 de cada 10 pacientes. (Cosgrove et al, 2003)

2. MRSA: situación actual

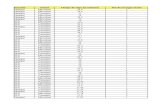

MRSA: proporción por países

MRSA en España

Los aislados de MRSA suponen un 48 % del total de S. aureus causantes de infección nosocomial (EPINE, año 2007)

5

14

s

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Año

• Medidas higiénicas y de contención: lavado de manos, ventilación, limpieza, aislamiento, barreras de precaución.

• Aislamiento de los pacientes colonizados o infectados por MRSA.

• Vigilancia de MRSA.

Control de MRSA

Vigilancia activa en la prevención y control de Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la meticilina (MRSA)

• Screening para la identificación de pacientes portadores:

• Cultivo • Mannitol Salt Agar + 2 % Oxacilina. • Medios cromogénicos.

• Métodos moleculares • PCR en tiempo real a partir de muestra

directa.

VIGILANCIA ACTIVA EN LA PREVENCIÓN Y CONTROL DE STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS

RESISTENTE A LA METICILINA (MRSA) La “vigilancia activa” es una de las mejores formas documentadas para prevenir la transmisión de MRSA

en hospitales. Este procedimiento implica un régimen de admisión en el que se incluya una prueba de

pacientes para detectar la presencia de MRSA1. La vigilancia activa también se puede llevar a cabo

periódicamente en ciertas áreas de riesgo, como la UCI.

La rápida identificación de MRSA en pacientes es primordial a la hora de iniciar las intervenciones

adecuadas para prevenir infecciones asociadas a MRSA. Los individuos infectados o colonizados pueden

ser aislados, tomando las precauciones de contagio necesarias, descolonizados y tratados casi

inmediatamente para minimizar la oportunidad de una mayor transmisión de MRSA e infección adicional de

pacientes.

RESUMEN DE VIGILANCIA ACTIVA

- Una vez que el test haya dado positivo, los pacientes deben ser aislados, descolonizados y /o

tratados, estableciendo un estricto control sobre las debidas precauciones a tomar y los protocolos

de higiene en manos.

- Las pruebas utilizadas en la vigilancia activa junto con otros métodos de prevención de infecciones

vienen establecidos por las directrices facilitadas por los siguientes organismos:

o La Sociedad Americana de Salud Epidemiológica (SHEA) 2

o La Asociación de Profesionales en Control de Infecciones y Epidemiología (APIC)3

o La CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) 4

- Las directrices de la SHEA indican claramente: “Los cultivos de vigilancia activa son esenciales

para identificar el reservorio de expansión de infecciones MRSA y VRE (Enterococcus resistente a

la vancomicina) y posibilitar el control mediante las precauciones anticontagio recomendadas por la

CDC 5.

- La vigilancia activa incluye testar a aquellos sujetos de alto riesgo susceptibles de MRSA, lo cual

puede incluir variables basadas en anteriores exposiciones, estilos de vida y factores sociales tales

como:

o Residencia en un centro de cuidados para mayores.

o Historial de diálisis y enfermedades renales, diabetes mellitas y/o cirugía.

o Historial de uso de catéteres o cualquier otro instrumento médico que vaya al cuerpo atra-

vesando la piel.

o Uso frecuente y/o reciente de antibióticos.

o Alta prevalencia de MRSA en la comunidad local o entre la población de pacientes.

o Contacto cercano con alguien infectado o colonizado con MRSA.

o Condiciones de vida de hacinamiento (por ej. Refugios para gente sin hogar, cárceles…).

o Infecciones entre deportistas por contacto de piel, heridas ya existentes o por compartir

ropa y/o equipación.

o Edad avanzada.

- En EEUU existen muchos hospitales que han implementado con éxito la vigilancia activa para

controlar epidemiológicamente MRSA y eliminar las infecciones asociadas. Ejemplos de programas

implementados con éxito incluyen: Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, Evanston, IL; el University

of Pittsburg Medical Center, Pittsburg, PA; el Newark Beth Israel Hospital en Newark, NJ; y el

University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD.

- Los métodos más nuevos de test moleculares rápidos son la tecnología ideal para implementar las

medidas de vigilancia activa. La obtención de resultados definitivos para MRSA en dos horas, en vez de dos o tres días siguiendo los métodos de cultivo tradicionales, permite tomar las debidas precauciones y poner un tratamiento casi inmediatamente. La rapidez del test ayuda

a minimizar el riesgo de complicaciones y transmisión, y evita la necesidad de mantener el

aislamiento mientras se esperan los resultados.

OTROS TIPOS DE VIGILANCIA DE MRSA

Vigilancia Universal, también conocida como vigilancia en todas las admisiones, incorpora el test a todos

los pacientes admitidos, no sólo a los pacientes de alto riesgo (según se describe arriba). Un nuevo estudio

publicado en la Sociedad Americana de Microbiología durante la 46 Conferencia anual sobre Agentes

Antimicrobianos y Quimioterapia (ICAAC) demostró que la implementación de la vigilancia universal es

mucho más efectiva a la hora de controlar MRSA que simplemente la pasiva o la activa dirigida hacia un

diana específica.

“Búsqueda y destrucción” es otra forma de aproximación que se utiliza con éxito en países como

Finlandia, Dinamarca y Holanda para mantener el MRSA en los más bajos niveles posibles. Implica la

utilización de una vigilancia activa en pacientes y personal sanitario, con una búsqueda de MRSA en el

momento de admisión y a ciertos intervalos en áreas de alto riesgo. Va acompañado de estrictas

precauciones anticontagio. También se pone énfasis en un uso juicioso de antibióticos de amplio espectro.

Vigilancia Pasiva implica testar solo aquellos en los que han aparecido signos clínicos o síntomas de

infección por MRSA. Es el método más habitual para identificar MRSA en pacientes hospitalarios en USA.

Consiste en una vigilancia no activa, que depende de cultivos rutinarios para identificar pacientes con

MRSA, no identifica el 85% de los pacientes colonizados de MRSA en admisión en el hospital. Los

pacientes identificados como portadores a través de una vigilancia activa son tratados de forma mucho

más rápida estableciendo rigurosas precauciones anticontagio para frenar la transmisión de la infección.

Los programas hospitalarios para controlar y prevenir la transmisión de MRSA no pueden ser efectivos sin

una vigilancia activa en los pacientes de admisión con un resultado de rápida implementación de medidas

anticontagio en aquellas personas identificadas como portadores de MRSA;

Vigilancia de MRSA en UCI mediante cultivo tradicional (Huang et al., 2006)

La vigilancia rutinaria de MRSA en UCI mediante cultivo permitió el establecimiento temprano de precauciones de aislamiento y se asoció con una reducción significativa de la incidencia de bacteriemia por MRSA. No se pudo atribuir ninguna reducción similar debida a otros métodos de control de la infección. Huang et al., 2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:971-978.

4. Vigilancia de MRSA en UCI

Prevalencia de SARM en el momento de la admisión Tasa de transmisión mensual

Transmisión de MRSA en UCI durante las fases de screening mediante cultivo o screening basado en PCR

Vigilancia de MRSA en UCI mediante RT-PCR: reducción de las transmisiones (Cunningham et al., 2007)

0

5

10

15

20

25

PCR

Se considera factible la búsqueda mediante PCR de pacientes portadores de MRSA durante la admisión a unidades de cuidados en el marco de la rutina clínica; proporciona resultados más rápidamente que el cultivo y se asocia con una reducción significativa en la subsiguiente transmisión de MRSA.

Control de MRSA

www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/jhin

Effect on MRSA transmission of rapid PCR testing of patients admitted to critical care

R. Cunningham a,*, P. Jenks a, J. Northwood a, M. Wallis a, S. Ferguson b, S. Hunt b

a Department of Microbiology and Infection Control, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK b Critical Care Unit, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK

Received 31 May 2006; accepted 15 September 2006 Available online 4 December 2006

KEYWORDS MRSA; PCR; Screening; Critical care

Summary Wereporta significant reduction in the rateofmeticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) transmission on a critical care unit when admission screening by culture was replaced with a same-day polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. This was an observational cohort study, set in a 19-bed mixed medical and surgical adult critical care unit in southwest England. We studied 1305 patients admitted between April 2005 and Febru- ary 2006. Standard MRSA culture methods were used to screen 612 patients between April 2005 and August 2005, and the IDI MRSA PCR test was used to screen 693 patients between September 2005 and February 2006. Stan- dard infection control precautions were instituted when positive results were obtained by either method. Outcome measures included carriage rate, turnaround time for results and rate of subsequent MRSA transmission on the unit. The overall carriage rate on admission to the unit was 7.0%. Culture re- sults were available in three working days, PCR results within one working day. The mean incidence of MRSA transmission was 13.89/1000 patient days during the culture phase and 4.9/1000 patient days during the PCR phase (relative risk reduction 0.65, 95% CI 0.28e1.07). PCR screening for MRSA on admission to critical care units is feasible in routine clinical practice, pro- vides quicker results than culture-based screening and is associated with a significant reduction in subsequent MRSA transmission. ª 2006 The Hospital Infection Society. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Address: Department of Microbiology and Infection Control, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, PL6 8DH, UK. Tel.: þ44 1752 7923 87; fax: þ44 1752 5177 25.

E-mail address: [email protected]

0195-6701/$ - see front matter ª 2006 The Hospital Infection Soc doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.09.019

Introduction

Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the most important causes of hospital- acquired infection in the UK. The spectrum of

iety. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

infection ranges from asymptomatic colonization to bacteraemia and death. Community-acquired MRSA is an increasing problem, but in the UK most severe MRSA infection is still hospital associated.

Within hospital, critical care units (CCUs) are a crucial site for MRSA control measures. Severe underlying illness, a high degree of comorbidity, intravascular lines and endotracheal intubation all contribute to high rates of MRSA transmission. Attempts have been made to reduce this by screening on admission followed by isolation, topical eradication therapy, and attention to hand hygiene.1e4 The results have been inconclu- sive, possibly because traditional culture methods for MRSA detection take at least two days. This means that positive patients remain undetected and act as a reservoir for transmission during the most intensive phase of their CCU stay. A recent study in Geneva described a reduction in MRSA in- fections on a medical intensive care unit (ICU), when a rapid molecular screening test was com- bined with pre-emptive isolation of all admissions until a negative result was obtained.5 They found no effect with screening alone, or when the strat- egy was applied to a surgical ICU.

In the present study, the impact of a rapid PCR test on MRSA transmission in a mixed medical and surgical CCU was compared with the preceding control period when patients were screened using a traditional culture method.

Methods

Setting and study population

Derriford Hospital is a 1200-bed teaching hospital in southwest England. The general adult CCU comprises a four-bed neurosurgical section, a six- bed high-dependancy unit, and a nine-bed ICU. The units are adjacent and linked, and share staff and equipment. The unit receives approxi- mately 1400 admissions each year, and the average length of stay is four days. The three siderooms available are not exclusively reserved for MRSA-positive patients, although where pos- sible, such patients are nursed in these rooms.

Culture-based MRSA screening

Screening of all CCU admissions and discharges was introduced in April 2005 as a quality improvement measure. Swabs were taken from the nose, throat, axillae and groin, and wounds if present. The

swabs were pooled in 7% sodium chloride broth and incubated overnight at 30C. They were sub- cultured on mannitol salt agar with oxacillin (2 mg/L) and incubated at 37C in air for 48 h. Sus- pected MRSA colonies were confirmed by standard methods. CCU staff were informed verbally of all positive results by an infection control nurse or consultant microbiologist. Electronic and printed results were issued the same working day. All pa- tients discharged from CCU were screened using the same method on the day of discharge.

PCR-based MRSA screening

From September 2005 culture-based admission screening was replaced with the IDI-MRSA PCR assay, run on the Cepheid Smart Cycler platform. The performance of the assay in the patient population was assessed in a pilot phase, when swabs from 174 patients were processed by culture and PCR in parallel. This showed a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 92%, consistent with pre- vious experience of the test. A single nose swab was collected on admission, and processed Monday to Friday on the same day according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Weekend samples were processed the following Monday. Positive and negative controls were included in each run. Any samples unresolved due to PCR inhibitors were repeated after a single freezeethaw cycle on the same DNA extract. All positive and unresolved swabs were cultured and full susceptibility testing of MRSA isolates performed using standard methods. Positive results were transmitted to CCU staff in the same way as for conventional culture, except that PCR results were reported as provisional, pending the final results from culture.

Infection control policies

A dedicated link nurse (S.H.) who is a senior sister on the CCU liaised with the infection control team and laboratory throughout both phases. Standard infection control procedures such as educational sessions and ward audits continued unchanged throughout. The National Patient Safety Agency ‘Clean your hands’ campaign began before screen- ing was introduced and continued throughout. No changes in ward cleaning, disinfectant use, line care or management of ventilators/endotracheal tubes occurred during the study period. Pre- emptive isolation of new admissions was not employed. Identified MRSA carriers were com- menced on nasal mupirocin ointment thrice daily and topical triclosan for five days. Patients with

26 R. Cunningham et al.

evidence of MRSA infection were treated with appropriate antibiotics, mainly vancomycin, rifam- picin, gentamicin and linezolid. Patient case notes and the computerized patient information system were tagged with their MRSA status, and standard infection control precautions were reinforced. Patients were nursed in a sideroom if available, but shortage of siderooms meant this was not always possible. Similar precautions were taken if MRSA was isolated from a routine culture later in the patients ICU stay.

Definitions

CCU acquired infection was defined as MRSA detection more than 48 h after admission, in a pa- tient whose admission screen had been negative. The transmission rate was defined as the number of CCU acquired cases divided by the number of bed days at risk, expressed as cases per 1000 bed days.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed with the non-parametric Wil- coxon test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Carriage rate

The overall pre-admission carriage rate throughout the period of study was 7.0%. Monthly rates ranged

between 3.6 and 10.8%, but there was no signifi- cant trend or difference between the culture and PCR phases. Rates are summarized in Figure 1.

Turnaround time

The turnaround time was three working days during the culture phase and less than one working day during the PCR phase.

Success rate of decolonization regimen

This was defined as MRSA culture negative at four weeks post-decolonization. It was 36% in the culture phase and 33% in the PCR phase (no significant difference).

MRSA transmission

Thirty-three out of 612 patients acquired MRSA on the CCU during the culture phase, and 14 out of 693 patients during the PCR phase. This gives a mean incidence of transmission of 13.89/1000 patient days during the culture phase and 4.90/ 1000 patient days during the PCR phase (P<0.05). The absolute reduction is 8.98 transmissions/1000 patient days (95% CI 8.56e9.42). The relative risk reduction is 0.65 (95% CI 0.28e1.07).

These results are summarized in Figure 1.

Discussion

These results suggest that rapid PCR screening of patients admitted to CCUs may reduce the rate of

0

5

10

15

20

25

Culture MRSA screening Mean transmission rate 13.9/1000 patient days

PCR MRSA screening Mean transmission rate 4.9/1000 patient days

Figure 1 MRSA transmission on CCU during culture and PCR-based screening phases. Columns represent transmission rate each month and the continuous line is the prevalence of MRSA at the time of admission.

MRSA PCR testing on Critical Care 27

subsequent MRSA transmission more effectively than traditional culture based methods. Possible explanations include earlier use of decolonization regimens, earlier use of appropriate antibiotics, earlier isolation, and better compliance with hand hygiene procedures.

It is not possible to define which of these factors is most important from the present data, but since the success rate of decolonization was similar in both phases of the study, we suspect that better compliance with hand hygiene and early use of topical eradication agents might be the most important mechanisms.

The reduction in turnaround time gained using the PCR test is substantial, since presumptive results are obtained early in the CCU stay, when nursing and medical care is most intensive. It could be reduced even further if the PCR test is made available at weekends. Eight patients admitted at the weekend were MRSA carriers, five during the culture phase and three during the PCR phase. Availability is limited by financial rather than technical constraints; the cost of the assay is approximately £25.00, but this would be increased by the staffing costs of a weekend service. PCR is clearly more expensive than bacterial culture, but should be considered in the context of an average cost of over £10 000 for a single CCU admission.

The PCR test is highly sensitive, but its speci- ficity is less good. This is difficult to quantify in a retrospective study as some patients with posi- tive PCR and negative cultures were already on antimicrobials or antiseptics active against MRSA. Some patients had been positive in the recent past, or were culture positive from other anatom- ical sites. This did not present major practical difficulties in the CCU population, since the main aim was not to miss any MRSA carriers. PCR results were initially reported as provisional and subject to confirmation. Patients with a false-positive PCR result would have been started on topical decolonization regimens unnecessarily, but we are not aware of any serious adverse consequences arising from this.

There were a number of interesting differences between our findings and those of Harbarth et al. in a Swiss ICU.5 First, despite a comparable pre- admission prevalence of MRSA in their cohort, over- all transmission rates on their ICUs were lower. This may be because they did not carry out discharge screening throughout the whole study period, which could potentially underestimate the transmission rate. It may also reflect increased availability of isolation rooms in the Swiss healthcare setting. Although their report does not state how many single rooms were available, they were able to isolate all

new admissions until MRSA screening results were available. This suggests a relatively generous provi- sion compared with most UK units.

Second, they did not observe any reduction in transmission until pre-emptive isolation was in- troduced. The present results suggest that benefit can be obtained from rapid results, even without the ability to isolate all new admissions in this way.

Finally, they found that rapid testing had no impact when applied on a purely surgical ICU. The present study included mixed medical and surgical high-dependancy, intensive care and neurosurgical intensive care patients. This is more representa- tive of routine UK practice, and provides some reassurance that the present results can be generalized to other similar units.

This is an observational study, and conse- quently has many limitations. We cannot exclude the possibility that other changes in MRSA epi- demiology or management influenced transmis- sion rates. We cannot identify any changes in antibiotic susceptibility or virulence over this period, neither can we identify any changes in patient management or infection control policy. The ‘Clean your hands’ campaign was most heavily promoted during the culture screening phase, and there is no reason to believe it had a greater impact when PCR screening began five months later. The PCR screening phase spanned the winter period, when hospital activity is highest. We have not performed a formal cost- effectiveness analysis, though the business case used to obtain funding for this initiative predicted significant overall savings with much smaller reductions in MRSA transmission than we subsequently observed.

The benefits of rapid MRSA PCR screening can only be determined by large randomized, con- trolled trials, with robust health economic anal- ysis. At least one such study is underway and will be vital in defining the best use for this technol- ogy. Details are available on the UK National Research Register Document, http://www.nrr. nhs.uk/ViewDocument.asp?ID=N0046162252. The results of this study suggest the possibility of sub- stantial benefits as well as grounds for optimism in the struggle to control MRSA in critical care.

References

1. Chaix C, Durand-Zaleski I, Alberti C, Brun-Buisson C. Control of endemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a costebenefit analysis in an intensive care unit. JAMA 1999;282:1745e1751.

2. Cepeda JA, Whitehouse T, Cooper B, et al. Isolation of pa- tients in single rooms or cohorts to reduce spread of MRSA

in intensive-care units: prospective two-centre study. Lancet 2005;365:295e304.

3. Rubinovitch B, Pittet D. Screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the endemic hospital: what have we learned? J Hosp Infect 2001;47:9e18.

4. Grundmann H, Hori S, Winter B, Tami A, Austin DJ. Risk factors for the transmission of methicilln-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus in an adult intensive care unit: fitting a model to the data. J Infect Dis 2002;185:481e488.

5. Harbarth S, Masuet-Aumatell C, Schrenzel J, et al. Evalua- tion of rapid screening and pre-emptive contact isolation for detecting and controlling methicillin-resistant Staphylo- coccus aureus in critical care: an interventional cohort study. Critical Care 2006 Feb 6;10:R25 [Epub ahead of print].

El impacto al utilizar métodos moleculares

Metodología tradicional: cultivo

12 h 36 h 48 h 60 h 72 h 84 h24 h 96 h

Cultivo

2-3 días de transmisión potencial de MRSA

12 h 36 h 48 h 60 h 72 h 84 h24 h 96 h

PCR

Las medidas de aislamiento y/o descontaminación se establecen el mismo día de la toma de muestra

Resultado en 2 horas

5. Control de MRSA: El impacto de utilizar métodos moleculares

BD GeneOhm™ MRSA

definitivos

6. BD GO. Rendimiento de la prueba y publicaciones

BD GeneOhm™ MRSA

Huletsky et al, 2004. New real time PCR assay for rapid detection of MRSA directly from specimen containing a mixture of staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42(5): 1875-1884. Sensibilidad: 98,7% Especificidad: 95,4%

Paule et al., 2007. Performance of the BD GeneOhm Methicillin- Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Test before and during High- Volume Clinical Use. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45(9): 2993-2998 Sensibilidad: 98% Especificidad: 96 % VPN: 99,7% VPP: 77 %

Sensibilidad: 93,1% Especificidad: 98,4%

Oberdorfer et al., 2006. Evaluation of a single-locus real-time polymerase chain reaction as a screening test for specific detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in ICU patients. Eu. J. Clin. Microbial. Infect. Dis. 25: 657-663. Sensibilidad: 92,3% Especificidad: 98,6% VPN: 99,6% VPP: 75 %

Wren et al., 2006. Rapid Molecular Detection of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44(4): 1604-1605. Sensibilidad: 95,0% Especificidad: 98,8% VPN: 99,6% VPP: 84,4%

Vigilancia de MRSA en pabellones quirúrgicos mediante RT- PCR: importancia de un diagnóstico rápido

Kesthgar et al., 2007 • El estudio demuestra una reducción significativa de

las bacteriemias debidas a MRSA al introducir una técnica rápida de screening, en comparación con el periodo donde no se realizaba screening.

• También se observa una reducción de las infecciones de herida por MRSA.

• El programa de screening es rentable, especialmente en años donde hay un pico en la incidencia de MRSA, y supone una mejora considerable en la calidad de vida de los pacientes.

Jog et al., 2007 • El screening mediante PCR combinado con la

supresión de MRSA en el momento de la cirugía cardiaca es viable dentro de la práctica clínica rutinaria y se asocia con una reducción significativa en las posteriores SSIs (Infecciones de Herida Quirúrgica) debidas a MRSA.

Control de MRSA: Cirugía

Abstract | References | Full Text: HTML

View Full Width

What is RSS?

Early View (Articles online in advance of print) Published Online: 27 Nov 2007 Copyright © 2007 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd. Published by John Wiley &

Sons, Ltd.

Advanced Search

Original Article

*Correspondence to M. R. S. Keshtgar, Department of Surgery, Royal Free Hospital, Pond Street, London NW3 2QG, UK

The Editors are satisfied that all authors have contributed significantly to this publication

Accepted: 12 November 2007

Introduction

The incidence of hospital-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is rising worldwide, over and above the increase in meticillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) infection. In the UK, the incidence of MRSA septicaemia increased by 5·5 per cent between 2001 and 2003-2004[1] with a corresponding rise in MRSA-related deaths[2]. Indeed, the UK is reported to have one of

Impact of rapid molecular screening for meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in

surgical wards

M. R. S. Keshtgar 1 *, A. Khalili 1, P. G. Coen 2, C. Carder 2, B. Macrae 2, A. Jeanes 2, P. Folan 2, D. Baker 2, M. Wren 2, A. P. R. Wilson 2

1Department of Surgery, Windeyer Institute of Medical Sciences, University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust, London, UK 2Department of Microbiology, Windeyer Institute of Medical Sciences, University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust, London, UK

email: M. R. S. Keshtgar ([email protected])

ABSTRACT

Background: This study aimed to establish the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of rapid molecular screening for hospital-acquired meticillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in surgical patients within a teaching hospital.

Methods: In 2006, nasal swabs were obtained before surgery from all patients undergoing elective and emergency procedures, and screened for MRSA using a rapid molecular technique. MRSA-positive patients were started on suppression therapy of mupirocin nasal ointment (2 per cent) and undiluted chlorhexidine gluconate bodywash.

Results: A total of 18 810 samples were processed, of which 850 (4·5 per cent) were MRSA positive. In comparison to the annual mean for the preceding 6 years, MRSA bacteraemia fell by 38·5 per cent (P < 0·001), and MRSA wound isolates fell by 12·7 per cent (P = 0·031). The reduction in MRSA bacteraemia and wound infection was equivalent to a saving of 3·78 beds per year (£276 220), compared with the annual mean for the preceding 6 years. The cost of screening was £302 500, making a net loss of £26 280. Compared with 2005, however, there was a net saving of £545 486.

Conclusion: Rapid MRSA screening of all surgical admissions resulted in a significant reduction in staphylococcal bacteraemia during the screening period, although a causal link cannot be established. Copyright © 2007 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

DIGITAL OBJECT IDENTIFIER (DOI)

the highest rates of MRSA infection in Europe[3].

MRSA-colonized patients may have acquired the bacterium from previous hospital and nursing home admission, but others are truly community acquired[3-5]. The identification of MRSA carriers on admission and use of topical suppression may reduce the rates of MRSA infection[6]. Previously, routine MRSA screening relied on culture techniques with a turnaround time of up to 3 days. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology now enables results to be reported within hours, so topical suppression protocols can start immediately.

The aim of the present study was to establish the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of rapid molecular screening for MRSA in surgical patients within a teaching hospital, and to monitor the effect of rapid screening and topical suppression therapy on the rate of MRSA wound infection and bacteraemia.

Methods

After obtaining ethics committee approval, all patients admitted in 2006 (January to December inclusive) to the University College London Hospitals (UCLH) Foundation Trust for critical care, routine or emergency surgery (i.e. incision) were targeted for rapid MRSA screening. In those scheduled for elective surgery, cotton swabs (in Amies transport medium) from both nostrils were taken in the preadmission clinic. In emergency patients, nasal swabs were obtained on admission to the ward. Swabs were analysed in batches of 30 to 46, two to three times daily during the working week. Positive and negative controls were included in each run for quality control.

PCR was performed using the GeneOhm® MRSA Test (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA), which achieves detection of MRSA in a nasal swab by target amplification with primers and probes designed to detect the right-hand region of the mecA cassette and neighbouring orfX gene. The amplified targets are detected by using fluorescent beacon technology[7]. Inhibited samples (those in which the internal control was not detected) were repeated after freezing the lysate at - 20 °C for approximately 2 h. If there was still inhibition on repeat, a further swab was requested and, if surgery was anticipated within 3 days, the suppression protocol was instigated.

When a patient was found to be MRSA positive, the appropriate doctor or preadmission clinic was informed by telephone and asked to contact the patient to prescribe the suppression protocol. Outpatients were asked to visit the hospital pharmacy to collect a prescription written by the microbiologist.

The suppression protocol was expected to start 5 days before surgery, or the operation might be delayed. In more urgent cases, the suppression protocol was commenced immediately. Mupirocin nasal ointment (2 per cent) was applied to the inside of the nostrils three times daily, and undiluted chlorhexidine gluconate 4 per cent (Hibiscrub®; Moinlycke Health Care, Dunstable, UK) was used as a bodywash. Patients were advised to use undiluted Hibiscrub® as a shampoo to wash hair on days 1, 3 and 5, and to change their clothing and bedlinen daily.

If antibiotic prophylaxis was required, existing practice was to use a combination of teicoplanin and gentamicin. Patients who required emergency surgery before the result of MRSA screening was available were given mupirocin nasal ointment and chlorhexidine wash. The suppressive measures were continued until the result of MRSA screening was known. Blood cultures were obtained when the temperature rose above 37·5 °C (either peripherally or from a central or arterial catheter).

The hospital wound surveillance team has examined surgical wounds in all specialties for at least 6 months every year since 2000 by a combination of observation, questioning of staff, examination of case notes, and telephone or postal contact with patients[8]. After discharge, surveillance was performed at 1-2 months. Patients were excluded from wound surveillance if they stayed in hospital for fewer than two nights or if the procedure did not involve wounding (for example, endoscopy alone).

Cost-effectiveness analysis The annual saving to the hospital attributable to the MRSA screening programme was assessed by comparing the numbers expected (E) in the absence of screening (using incidence rates for 2000-2005 and for 2005 alone) with the observed numbers (O) for 2006. The saving is given by the expression (E - O) × C, where C is the cost per bacteraemia (or wound). C was calculated from the mean treatment costs for MRSA bacteraemia (£3500) and wound infection (£4018), primarily through prolonged hospital stay[8][9]. The estimated daily labour costs (all staff) of looking after an infected patient at UCLH was £314 in a general ward, £1002 in the high- dependency unit and £1390 in the intensive care unit (ICU)[8]. Other costs, such as dressings, drainage and antibiotics, accounted for only 2 per cent of costs. The saving was then translated into bed-years using the benchmark cost of an average medical/surgical bed (£200 above the estimated trimpoint - the point after which a length of stay is determined to be abnormally long).

The cost-effectiveness of the programme was calculated by comparing the saving with the annual cost of screening (including reagents, equipment and staffing).

Statistical analysis Most statistical tests were performed using Stata

TM version 9.0 (StatCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Incidence rates were

compared with Fisher's exact test. The 2 test for trends was used to assess monthly and quarterly changes in MRSA prevalence on admission screening. Time to event data were collected for inpatients with positive MRSA screening results and analysed by means of survivorships between January and September 2006. Median times to event and their 95 per cent confidence intervals (c.i.) were calculated from the time to 50 per cent survival in Kaplan-Meier survivorships. For estimates of screening compliance, each surgical operation was considered compliant with the screening protocol if the inpatient had been screened within 6 months before and 2 weeks after surgery.

Results

Between 16 January and 31 December 2006, 20 447 screening samples were received, of which 18 810 were processed. The remaining samples were discarded as they were from inappropriate sites (n = 627), duplicate nares (n = 423) or patients found to be MRSA positive on a previous screen (n = 587).

There were 850 MRSA-positive samples (4·5 per cent of all samples processed). Patients admitted for emergency surgery were more likely to be colonized (99 of 1854 patients; 5·3 per cent) than those undergoing elective surgery (289 of 7938; 3·6 per cent; 2 = 10·9, P = 0·001), resulting in an overall prevalence of 4·0 per cent for all surgical admissions. Table 1 shows MRSA isolates stratified by surgical specialty and ICU admission. A continuous audit of surgical prophylaxis (as part of the wound surveillance programme) showed no policy changes in antibiotic prophylaxis effective against MRSA between 2000 and 2006[8]. Tests for trend failed to reveal statistically significant changes in the prevalence of MRSA positivity on admission during 2006.

Processing of specimens A total of 215 positive admission episodes were audited. Median time lags for the processing of positive samples are shown in Table 2. The busiest days for laboratory processing were Monday and Tuesday, as a result of the backlog of unprocessed samples collected during the weekend.

MRSA bacteraemia Fifty-three patients developed MRSA bacteraemia over the study interval, 41 in screened and 12 in non-surgical patients. The annual

Table 1. Proportion of patients with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization on admission

Surgical specialty Elective surgery Emergency surgery Total

Anaesthetics 2 of 95 (2) 0 of 11 (0) 2 of 106 (1·9)

Cardiothoracic 25 of 1184 (2·1) 7 of 186 (3·8) 32 of 1370 (2·3)

General surgery 59 of 1459 (4·0) 21 of 279 (7·5) 80 of 1738 (4·5) Maxillofacial 51 of 977 (5·2) 9 of 163 (5·5) 60 of 1140 (5·3)

Orthopaedics 40 of 1813 (2·2) 30 of 652 (4·6) 70 of 2465 (2·8)

Plastics 15 of 225 (6·7) 16 of 415 (3·9) 31 of 640 (4·8)

Urology 84 of 1929 (4·4) 9 of 81 (11) 93 of 2010 (4·7)

Vascular 13 of 254 (5·1) 2 of 38 (5) 15 of 292 (5·1) Unknown 0 of 2 (0) 5 of 29 (17) 5 of 31 (16)

All specialties 289 of 7938 (3·6) 99 of 1854 (5·3) 388 of 9792 (4·0)

ICU n.r. n.r. 235 of 2736 (8·6)

Values in parentheses are percentages. ICU, intensive care unit; n.r., not recorded.

Table 2. Median time lag for events in the processing of positive samples

Time lag

13·7 (9·78, 15·1) h

From receipt of sample in laboratory to obtaining result (n = 212)*

21·8 (21·0, 22·5) h

From obtaining result to telephone call (n = 215)* 1·03 (0·83, 1·41) h

From receipt of sample in laboratory to start of

surgery (n = 217)

days

From start of suppression to surgery (n = 200) § - 0·42 (-1·90 to 2·85)

days

median (interquartile range).

A negative value indicates that surgery took place before the sample had been processed. § If less than 5 days to surgery, then suppression continued into the postoperative period.

means and ranges for 2000-2005 were 67 (53-87) and 29 (17-45) respectively in the equivalent patient populations.

The overall rate of MRSA bacteraemia per 1000 patient-days fell by 38·6 per cent compared with 2005 (P < 0·001; two-tailed Fisher's exact test) and by 38·5 per cent compared with the annual mean for 2000-2005 (P < 0·001) (Table 3). In addition, there was a 32·1 per cent reduction in MSSA bacteraemia compared with 2005 (P < 0·001) and a 30·4 per cent reduction compared with the annual mean for 2000-2005 (P < 0·001) (Table 3).

MRSA wound infection The rate of isolation of MRSA from wounds fell by 27·9 per cent compared with 2005 (P < 0·001) but by only 12·7 per cent compared with the annual mean between 2000 and 2005 (P = 0·021) (Table 3). The 2006 MSSA isolation rates did not change significantly compared with those for 2005 (4·4 per cent reduction; P = 0·430), but increased by 12·7 per cent compared with 2000-2005 (P = 0·006) (Table 3). Although there was a reduction in wound infection in seven of 11 specialties covered by wound surveillance, the overall prevalence was unchanged because of a rise in wound infection in general surgery (surveillance data available only for January to July 2006).

MRSA isolates There were no significant differences in the proportion of mupirocin resistance (predominantly low levels) in wound and blood isolates between 2005 and 2006: 93 (13·9 per cent) of 671 versus 74 (15·7 per cent) of 472 isolates (P = 0·396). In surgical and critical care patients in 2000-2006, 11 (6·7 per cent) of 163 isolates tested (281 not tested) were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and 54 (12·3 per cent) of 438 (six not tested) were sensitive to erythromycin.

Compliance with screening and treatment Compliance with screening in different surgical specialties improved during 2006 (Fig. 1). Of 218 audited patients found to have MRSA at or before surgery, 92 either received no topical suppression or it was started only after the procedure. In 30 (33 per cent) of these patients MRSA was later isolated from the surgical wound. The other 126 patients received suppression (at least one dose) before the procedure; in 26 (20·6 per cent) of these patients MRSA was later isolated from the wound (P < 0·05, 2 test).

Costings Table 4 shows that the observed reduction in MRSA bacteraemia and wound infection rates was equivalent to a saving of 3·78 beds per year (£276 220) compared to the annual mean for the preceeding 5 years. The reduction in infection rates was observed both in patients who were screened and in those who were not; in many wards these patients were mixed, so separate costings have not been attempted.

Table 3. Incidence rates for meticillin-resistant and meticillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and wound infection

Year No. of patient-days

Bacteraemia Wound Bacteraemia Wound

2000-2005 1 469 399 0·39 (573) 1·44 (2110) 0·59 (860) 2·58 (3788) 2005 186 867 0·39 (73) 1·74 (325) 0·60 (112) 3·04 (568)

2006 221 027 0·24 (53) 1·25 (277) 0·41 (90) 2·90 (642)

Values in parentheses are numbers of patients. MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, meticillin-sensitive S. aureus.

Figure 1. Screening compliance stratified by elective and emergency surgery. Compliance was measured as the percentage of surgical episodes classified as screened. Dotted and dashed horizontal lines indicate 80 and 70 per cent compliance respectively [Normal View 25K | Magnified View 36K]

Table 4. Cost-effectiveness of the rapid meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus test screening programme

MRSA MSSA

Based on 2000-2005 figures 86 317 129 570 Observed numbers

2006 53 277 90 642

The annual cost of screening was estimated at £302 500 (cost per test: kit £11·59 including value added tax and cost of repeats, £1 for disposable tips, £1 for telephoning results and £3·01 per test for labour; less previous annual spending of £9900), which is equivalent to 4·1 beds for the year. The programme is therefore cost-effective and demonstrates large cost savings when compared to costs incurred during years of peak incidence (for example, 2005).

Discussion

In 2004, the UK Department of Health set a target of a 60 per cent reduction in MRSA bacteraemia by 2008. In January 2006, UCLH became the first National Health Service Trust (public sector corporation) nationally to introduce a rapid molecular MRSA detection technique for routine screening of most surgical patients. Before the start of this project, validation of the technique against culture showed a sensitivity of 95·0 per cent and a specificity of 98·8 per cent, with a positive predictive value of 84·4 per cent and a negative predictive value of 99·6 per cent[7].

Although more than 40 different decolonization regimens have been tested during the past 60 years, topical intranasal application of mupirocin ointment and bodywash with 4 per cent chlorhexidine has proven to be the most effective measure[10]. However, showering of all patients with chlorhexidine before surgery is not effective in reducing surgical infection rates[11].

This study demonstrated a significant reduction in the MRSA bacteraemia rate of 38·5 per cent compared with 2000-2005 figures and 38·6 per cent compared with 2005. A possible explanation is the reduction in the turnaround time for reporting of the MRSA screening swab, such that the suppression protocol and appropriate surgical prophylaxis can be started quickly. There was no other change in the authors' practice, as careful attention to hand hygiene and specific surgical prophylaxis for MRSA carriers had been in place well before the start of this study. These results need to be interpreted with caution, however, as in 2005, 4 months before the commencement of screening, most inpatients had been moved to a new building - this coincided with an increased incidence of MRSA infection. Hence, comparison was made not only with 2005 but also with the preceding 6 years.

The effect on wound infection was modest in comparison with that on blood isolates. There is an appreciable recurrence of superficial MRSA colonization following topical suppression. Unlike bacteraemia, wound infection can be prolonged.

MRSA infection has a cost for the patient and healthcare providers that includes prolonged hospital stay and treatment of complications associated with the infection. Variations in MRSA infection rate, such as the peak reported in 2005, can make it difficult to assess the effect of a screening programme. Although the screening programme is costly, the reduction in MRSA surgical wound infection and bacteraemia produces nearly equivalent savings and the improvements in quality of life for patients are considerable.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Elizabeth O'Donnell and the wound surveillance team, microbiology laboratory staff, the UCLH infection control nurses, the surgical preadmission clinic and UCLH ward and pharmacy staff.

Becton Dickinson funded production of a video presentation of the use of topical suppression for the benefit of patients and staff.

Cost savings (£)

Versus 2005 figures £115 500 £429 926 £147 000 £120 540 £812 966

Bed-year equivalents 1·58 5·89 2·01 1·65 11·1

Versus 2000-2005 figures £115 500 £160 720 £136 500 - £289 296 £123 424 Bed-year equivalents 1·58 2·20 1·87 - 3·96 1·69

MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, meticillin-sensitive S. aureus.

REFERENCES

1 National Audit Office. Improving Patient Care by Reducing the Risk of Hospital Acquired Infection: a Progress Report. Stationery Office: London, 2004.

2 Grandey M, Gorton R, O'Hara A, Hollyoak V. Communicable Diseases in the North East of England - Health Protection Agency North East. North East Public Health Observatory: Stockton on Tees, 2004.

3 Gould IM. The clinical significance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 2005; 61: 277-282. Links 4 Coello R, Jiménez J, García M, Arroyo P, Minguez D, Fernández C et al. Prospective study of infection, colonization and carriage

of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an outbreak affecting 990 patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1994; 13: 74- 81. Links

5 Tristan A, Bes M, Meugnier H, Lina G, Bozdogan B, Courvalin P et al. Global distribution of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 2006. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13: 594-600. Links

6 Schelenz S, Tucker D, Georgeu C, Daly S, Hill M, Roxburgh J et al. Significant reduction of endemic MRSA acquisition and infection in cardiothoracic patients by means of an enhanced targeted infection control programme. J Hosp Infect 2005; 60: 104- 110. Links

7 Wren MWD, Carder C, Coen PG, Gant V, Wilson APR. Rapid molecular detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44: 1604-1605. Links

8 Wilson AP, Hodgson B, Liu M, Plummer D, Taylor I, Roberts J et al. Reduction in wound infection rates by wound surveillance with postdischarge follow-up and feedback. Br J Surg 2006; 93: 630-638. Links

9 Cosgrove SE, Qi Y, Kaye KS, Harbarth S, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. The impact of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia on patient outcomes: mortality, length of stay, and hospital charges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005; 26: 166-174. Links

10 Boyce JM. MRSA patients: proven methods to treat colonization and infection. J Hosp Infect 2001; 48(Suppl A): S9-S14. Links 11 Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev 2007; (2)CD004985. Links

Journal of Hospital Infection (2008) 69, 124e130

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Impact of preoperative screening for meticillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus by real-time polymerase chain reaction in patients undergoing cardiac surgery

S. Jog a, R. Cunningham a, S. Cooper a, M. Wallis a, A. Marchbank b, P. Vasco-Knight a, P.J. Jenks a,*

a Department of Microbiology and Infection Prevention and Control, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK b Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth, UK

Received 18 October 2007; accepted 20 February 2008 Available online 2 April 2008

KEYWORDS MRSA; Polymerase chain reaction; Screening; Cardiac surgery; Surgical site infection

* Corresponding author. Address: Dep UK. Tel.: þ44 01752 792366; fax: þ44

E-mail address: Peter.Jenks@phnt.

0195-6701/$ - see front matter ª 200 doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2008.02.008

Summary We report a significant reduction in the number of surgical site infections (SSIs) due to meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients undergoing cardiac surgery after the introduction of preopera- tive screening using a same-day polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. This was an observational cohort study set in a cardiac surgery unit based in southwest England. We studied 1462 patients admitted for cardiac surgery between October 2004 and September 2006. The IDI MRSA PCR test was used preoperatively to screen 765 patients between October 2005 and Sep- tember 2006. Patients identified as carriers were treated with nasal mupir- ocin ointment and topical triclosan for five days, with single-dose teicoplanin instead of flucloxacillin as perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. The rate of SSI following cardiac surgery in this group was compared to 697 patients who underwent surgery without screening between October 2004 and September 2005. After introduction of PCR screening, the overall rate of SSI fell from 3.30% to 2.22% with a significant reduction in the rate of MRSA infections (relative risk reduction: 0.77; 95% confidence interval:

artment of Microbiology, Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth PL6 8DH, 01752 517725. swest.nhs.uk

8 The Hospital Infection Society. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

MRSA PCR screening in cardiac surgery 125

0.056e0.95). PCR screening combined with suppression of MRSA at the time of cardiac surgery is feasible in routine clinical practice and is associ- ated with a significant reduction in subsequent MRSA SSIs. ª 2008 The Hospital Infection Society. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Surgical site infections (SSIs) contribute substan- tially to morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery.1e4 Deep sternal wound infections may ex- tend into the mediastinum, require aggressive combined medical and surgical management, and have a mortality as high as 47%.3,5e9 Meticillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a leading cause of SSI following cardiac surgery and is inde- pendently associated with increased patient mor- tality, prolonged length of stay and higher hospital costs.1,10 Prior to the study, MRSA was the major cause of SSIs following cardiac surgery at our hospital, being responsible for more than 50% of cases. Nasal carriage of S. aureus has been identified as an important risk factor for sternal wound infections.11 Elimination of S. aureus nasal carriage using perioperative intranasal mupirocin has been shown to be effective in reducing sternal wound infections in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, as well as MRSA SSIs following orthopaedic surgery.12e16 Since the widespread use of mupiro- cin has the potential to increase the rate of resis- tance, it may be prudent to restrict prophylaxis to those found to be colonised.17 Identifying car- riers of MRSA would also highlight the requirement for additional infection control precautions, in- cluding isolation, as well as the need for a different systemic antibiotic for perioperative prophylaxis. Rapid diagnostic testing now allows MRSA screening in the immediate preoperative period with suffi- ciently short turnaround time to allow the imple- mentation of appropriate control measures before surgery. In the present study, the impact of rapid preoperative detection of MRSA on the develop- ment of SSIs in patients undergoing cardiac surgery was compared with the preceding control period when patients were not screened.

Methods

Setting and study population

Derriford Hospital is a 1200-bed teaching hospital in southwest England. The Southwest Cardiac

Surgery Unit comprises a seven-bed intensive care unit, a six-bed high-dependency unit and a 32-bed general ward. Each ward has its own dedicated staff and equipment. The seven single rooms available are not exclusively reserved for MRSA-positive patients, although where possible, such patients are nursed in these rooms. Approx- imately 750 patients undergo cardiac surgery each year and the average length of stay is 7.2 days. Elective patients are admitted the day before their operation. The study population comprised pa- tients undergoing cardiac surgery at the Southwest Cardiac Surgery Unit between October 2004 and September 2006.

The Plymouth cardiac care pathway

An assay for MRSA screening of all preoperative cardiac surgery patients was introduced as a quality improvement measure in September 2005. The lack of a pre-assessment clinic meant that determining MRSA status in advance of admission was difficult. Rapid diagnostic testing for MRSA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was therefore performed on patients admitted the day before surgery. A single nose swab was collected in Stuart’s medium from each patient on admission. Topical MRSA suppression therapy, consisting of na- sal mupirocin 2% ointment thrice daily and topical triclosan 2%, was then immediately commenced pending the result of the PCR assay. If the MRSA screening result was negative, mupirocin and tri- closan were discontinued and the patient received standard, previously used perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis of a single dose of gentamicin (3e 5 mg/kg depending on renal function) and flucloxa- cillin (1 g every 6 h for 24 h). If the PCR result was positive, mupirocin and triclosan were continued for five days (as per national guidelines for suppres- sion of MRSA) and the patient was given single doses of gentamicin (3e5 mg/kg) and teicoplanin (400 mg) as perioperative prophylaxis.18 This latter regimen was followed for patients previously colonised with MRSA regardless of any subsequent screening results, patients with unknown MRSA status and patients who have been on the ward for more than 96 h since their last screen.

126 S. Jog et al.

PCR-based MRSA screening

MRSA screening was performed with the Gene Ohm

MRSA Test (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA), run on the Cepheid Smart Cycler as previously described.19 Briefly, a single nose swab was processed Monday to Friday on the same day according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Weekend samples were processed the following Monday. An internal control detected the presence of substances inhibitory to PCR. Positive and nega- tive samples were included in each run. Any samples unresolved due to PCR inhibitors were repeated after a single freezeethaw cycle on the same DNA extract. All positive and unresolved swabs were cultured and full susceptibility testing of MRSA isolates performed using standard methods. Positive PCR results were reported as provisional, pending the final results from culture.

Nasal swab culture and performance of the assay

The same nasal swabs used for the PCR assay were also cultured at two different steps of the assay procedure. Direct culture was performed onto chromID MRSA agar (bioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and enrichment culture was performed after the assay procedure. For the latter, the swabs were incubated overnight in trypic soy broth containing 6.5% NaCl at 35 C before subculture onto chromID MRSA and 5% sheep blood agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) with a 1 mg oxacillin disc.

Positive results for MRSA by the real-time PCR assay were designated as true or false positives on the basis of nasal swab cultures and whether the patient had any other cultures positive for MRSA during a 7-day period before or after the date on which the PCR was performed. In order to de- termine the extent of colonisation, a full culture screen of nose, groin and throat swabs was performed on patients found to be MRSA carriers by the PCR method.

Infection control policies

Standard infection control procedures, such as ward audits and education, and a daily ward round on the cardiac surgery unit by a microbiologist (P.J.) continued unchanged. The National Patient Safety Agency ‘Cleanyourhands’ campaign was launched across the Trust in February 2005 and was piloted on the Cardiac wards from June 2004. No changes in ward cleaning, disinfectant use, line care or management of ventilators/endotracheal

tubes occurred during the control or study periods. Similar precautions were taken when MRSA was isolated on the preoperative screen or from a later culture in the patient’s stay. Patient case notes and the computerised patient information system were tagged with their MRSA status and standard infection control precautions were reinforced. Patients were nursed in a single room if available, but shortage of single rooms meant that this was not always possible. Patients with evidence of MRSA infection were usually treated with vanco- mycin and rifampicin.

Surveillance of surgical site infection

The outcomes were the overall rate of SSI follow- ing cardiac surgery and those due to individual micro-organisms. Prospective surveillance of SSI was performed by a dedicated surveillance clerk using the protocol established by the English Health Protection Agency.20 The following vari- ables were recorded: age, sex, dates of admission, surgery and discharge, duration of operation, sur- geon, underlying disease, use of immunosuppres- sive drugs, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, use of topical antimicrobials and antibiotic prophylaxis. During admission, the clinical records of all patients were studied for the development of SSI. After discharge from hospital, follow-up reviews were performed in outpatient clinics. All patients were checked to see whether they were readmitted to the hospital and whether this read- mission was due to a wound infection. For SSI, the date of onset, site (sternal or donor), type (super- ficial, deep or organ space) and pathogens in- volved were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Chi-squared test. P< 0.05 was considered significant. Koopman’s likelihood-based approximation was used to con- struct confidence for relative risk.21

Results

Between October 2005 and September 2006, 765 cardiac operations were performed at our hospi- tal. In total, 681 (89%) of these patients were screened for MRSA using the real-time PCR assay. The assay primers were changed part-way through the study and the sensitivity and specificity of the assay using these second-generation primers was 84.6% and 100% respectively (Table I). The positive

Table I Results for the performance of the IDI testa

IDI result Culture result

MRSA negative 407 2 MRSA positive 0 11

a Sensitivity, 84.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 60.5e 97.1%]; specificity, 100% (95% CI: 99.3e100%); positive pre- dictive value, 100% (95% CI: 77.9e100%); negative predictive value, 99.5% (95% CI: 98.4e99.9%).

Table III Micro-organisms causing surgical site infection (SSI) before and after screening for meticil- lin-resistant S. aureus by polymerase chain reaction

Micro-organism No. of SSIs before

screening

Meticillin-susceptible S. aureus 0 1 Coagulase-negative staphylococci 5 5 Coliforms/Pseudomonas spp. 7 6 Other 3 3

Total 23 17 a P< 0.05.

MRSA PCR screening in cardiac surgery 127

predictive value was 100% and positive and nega- tive predictive value 99.5% (Table I). Nineteen pa- tients were positive for MRSA, giving a prevalence of MRSA colonisation in patients who underwent cardiac surgery at our hospital of 2.5%. Of the 19 MRSA-positive patients, 18 were screened prior to the surgery and one after the procedure (a proced- ural error that occurred shortly after the screening protocol was introduced). Topical MRSA suppres- sion therapy and appropriate perioperative pro- phylaxis were prescribed in 17 patients.

In the 12-month period before screening was introduced, 697 procedures were performed with an overall SSI rate of 3.30%, with eight infections due to MRSA (Tables II and III). During the 12-month period following the introduction of screening, al- though the overall SSI rate fell to 2.22%, this did not reach statistical significance. However, there was a significant reduction in the rate of MRSA infection from 1.15% to 0.26% (P< 0.05; relative risk reduction 0.77; 95% CI: 0.056e0.95), which was independent of any underlying risk factors (as defined by Gaynes et al.22). There was no asso- ciated increase in the proportion of infections due to other micro-organisms (Table III).

None of the patients identified preoperatively as being MRSA carriers developed SSI or other postoperative infections due to MRSA. Of the two MRSA SSIs that occurred after the introduction of screening, one was a deep MRSA sternal wound infection that occurred in a patient who was not

Table II Surgical site infection (SSI) rates 12 months before and after screening for meticillin-resistant S. aureus by polymerase chain reaction

Type of infection

Sternal Leg Total Sternal Leg Total

Superficial 1.72 0.29 2.01 0.79 0.39 1.18 Deep 0.43 0.14 0.57 0.52 0 0.52 Organ space 0.72 0 0.72 0.52 0 0.52

Total 2.87 0.43 3.30 1.83 0.39 2.22

screened preoperatively and did not receive top- ical suppression therapy or teicoplanin prophy- laxis. The second occurred in a patient who was MRSA PCR-negative preoperatively and was re- admitted from another hospital with a deep MRSA sternal wound infection 20 days after surgery. During the study, two other patients, who were both MRSA-negative preoperatively, developed MRSA infection at other sites: one at a chest drain site 26 days after surgery and another at a trache- ostomy site 40 days after surgery.

Discussion

Our study shows that rapid PCR screening is an effective method of identifying nasal colonisation with MRSA in preoperative cardiac surgery pa- tients. Similar results may be seen when screening is performed using conventional culture methods. However, the reduction in turnaround time gained using the PCR test is substantial. This is particu- larly useful in situations when pre-admission as- sessment of MRSA carriage by conventional methods is impracticable and when patients are admitted shortly before their procedure. Rapid screening on admission is also useful for emer- gency cases and will identify MRSA acquisition that occurs during the period between pre-operative assessment and admission for surgery. Our study also shows that the use of decolonisation regimens and targeted surgical prophylaxis is effective at preventing MRSA SSIs in individuals colonised with this bacterium. The addition of teicoplanin to standard perioperative prophylaxis, as well as the use of topical suppression therapy, may explain why we observed a significant reduction in MRSA SSIs whereas other studies that have examined intranasal mupirocin alone have not.23e25

128 S. Jog et al.

Compliance with the screening was high and was achieved through education and incorporating the protocol into the patient surgical care plan. In particular, a prompt to perform screening was added to the admission checklist for nursing staff and reminder to check MRSA status added to the anaesthetic preoperative assessment. The preva- lence of MRSA carriage in this cohort was compar- able to that reported in similar cardiac centres, as well as other local elective surgical popula- tions.26,27 The sensitivity of the assay reported by us was lower than that reported in other stud- ies.28e30 All three patients with false-negative na- sal PCR screens grew MRSA from concurrent groin swab cultures. Currently the IDIeMRSA PCR assay is only validated for nasal specimens and although combined processing of nose and groin swabs would avoid such false-negative results, the over- all sensitivity of the assay may be compromised when used for extra-nasal samples.30,31

Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of mupirocin to suppress nasal carriage of S. aureus reduces SSI and is cost-effective in patients under- going cardiothoracic surgery.12e15 However, the risk of selecting mupirocin-resistant strains has led to recommendations that prophylaxis be limited to those found to be colonised with MRSA.32,33 The finding that none of the patients identified as being MRSA carriers by screening developed surgical site or other postoperative infections due to MRSA sup- ports both the targeted use of measures to suppress this organism at the time of surgery and the practice not to delay surgery pending attempted eradication of the organism.

A total of four MRSA infections, including two SSIs, were observed in patients who were either not screened or found to be MRSA-negative by PCR. One MRSA SSI occurred in the first month of the screening programme in a patient who was in- advertently not screened and did not receive MRSA suppression therapy or teicoplanin prophylaxis. The other MRSA SSI and two MRSA infections at non-surgical sites were observed in patients who were found preoperatively to be MRSA-negative by PCR. One of these three cases had a negative MRSA PCR as well as a negative three-site culture screen, and it is likely that this infection was acquired during the postoperative period. Another patient who was found to be MRSA-negative prior to surgery had a repeat nasal MRSA PCR test 33 days following surgery. This test was positive and screening swabs revealed extensive colonisation with MRSA; the patient subsequently developed an infection of the tracheostomy site. The PCR results probably reflected the colonisation status of the patient and the fact that infection occurred after

the surgical procedure. These cases emphasise that maintaining high infection control standards throughout the patient’s stay in hospital are essential to prevent acquisition of infection in the period following surgery. The final patient, who was re-admitted from another hospital with SSI, first had MRSA isolated from the sternal wound. Although this infection may also have been acquired following surgery, it is also possible that MRSA colonisation was present preoperatively at an extra-nasal site and was not detected by the PCR test.

Although the fall in the number of cases of MRSA was associated with a reduction in the overall SSI rate, this did not reach statistical significance. However, our data support previous studies show- ing that suppression of MRSA does not result in a significant compensatory increase in the rate of infections due to other species.25 Similar results have been observed in the three quarters following the study period, with 557 procedures performed with an infection rate of 1.6% and no postoperative SSIs due to MRSA. Furthermore, the number of MRSA bacteraemias has fallen from nine in the year prior to the introduction of screening to three in the last 12-month period.

This is an observational study, and consequently has many limitations. We cannot exclude the possibility that changes in MRSA epidemiology or management influenced infection rates. We can- not identify any changes in antibiotic susceptibility or virulence of MRSA over this period. We have not identified any changes in patient management or infection control policy, and there were no signif- icant changes in surgical personnel during the study period. The cost of the assay is about £25.00, but should be considered in the context of the cost of a deep sternal infection, which we estimate locally to be more than £10,000. Our data predict that it is necessary to screen 113 patients, at a cost of about £2825, in order to prevent one MRSA SSI. We have not performed a formal cost- effectiveness analysis, though the business case used to obtain funding for this initiative predicted significant overall savings with much smaller re- ductions in MRSA SSIs than we subsequently ob- served. The business model used predicted significant savings from targeted rather than uni- versal use of mupirocin and teicoplanin. Restrict- ing the use of the agents to those proven to be carriers of MRSA would also be expected to reduce the likelihood of toxicity or the risk of an overall increase in resistance.

Ultimately the benefits of rapid MRSA screening can only be determined by large randomised controlled trials, with robust economic analysis.

MRSA PCR screening in cardiac surgery 129

However, the results of this study suggest that preoperative screening by real-time PCR has a sub- stantial impact on postoperative MRSA SSIs in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Conflict of interest statement None declared.

Funding sources None.

2. Parisian Mediastinitis Study Group. Risk factors for deep sternal wound infection after sternotomy: a prospective, multicenter trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;111: 1200e1207.

3. Loop FD, Lytle BW, Cosgrove SE, et al. Maxwell Chamberlain memorial paper. Sternal wound complications after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: early and late mortality, morbidity, and cost of care. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;49: 179e187.

4. Kohman LJ, Coleman MJ, Parker FB. Bacteremia and sternal infection after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;49:454e457.

5. Grossi EA, Culliford AT, Krieger KH, et al. A survey of 77 ma- jor infectious complications of median sternotomy: a review of 7,949 consecutive operative procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 1985;40:214e223.

6. Serry C, Bleck PC, Javid H, et al. Sternal wound complica- tions: management and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980;80:861e867.

7. Farinas MC, Gald Peralta F, Bernal JM, Rabasa JM, Revuelta JM, Gonzalez-Macias J. Suppurative mediastinitis after open-heart surgery: a caseecontrol study covering a seven-year period in Santander. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20: 272e279.

8. Cheung EH, Craver JM, Jones EL, Murphy DA, Hatcher Jr CR, Guyton RA. Mediastinitis after cardiac valve operations: impact on survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985;90: 517e522.

9. Abboud CS, Wey SB, Baltar VT. Risk factors for media- stinitis after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77: 676e683.

10. Engemann JJ, Carmeli Y, Cosgrove SE, et al. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resis- tance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:592e598.

11. Kluytmans JA, Mouton JW, Ijxerman EP, et al. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus as a major risk factor for wound infections after cardiac surgery. J Infect Dis 1995;171: 216e219.

12. Cimochowski GE, Harostock MD, Brown R, Bernardi M, Alonzo N, Coyle K. Intranasal mupirocin reduces sternal wound infection after open heart surgery in diabetics and non-diabetics. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:1572e1579.

13. VandenBergh MF, Kluytmans JA, van Hout BA, et al. Cost- effectiveness of perioperative mupirocin nasal ointment in

cardiothoracic surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17:786e792.

14. Kluytmans J. Reduction of surgical site infections in major surgery by elimination of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 1998;40:S25eS29.

15. Kluytmans JA, Mouton JW, VandenBergh MF, et al. Reduc- tion of surgical-site infections in cardiothoracic surgery by elimination of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus. In- fect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17:780e785.

16. Wilcox MH, Hall J, Pike H, et al. Use of perioperative mupir- ocin to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) orthopaedic surgical site infections. J Hosp Infect 2003;54:196e201.

17. Miller MA, Dascal A, Portnoy J, Mendleson J. Develop- ment of mupirocin resistance among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after widespread use of nasal mupir- ocin ointment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17: 811e813.

18. Coia JE, Duckworth GJ, Edwards DI, et al. Guidelines for the control and prevention of meticillin-resistant Staphylococ- cus aureus (MRSA) in healthcare facilities by the Joint BSA- C/HIS/ICNA Working Party on MRSA. J Hosp Infect 2007;63S: S1eS44.

19. Cunningham R, Jenks P, Northwood J, Wallis M, Ferguson S, Hunt S. Effect on MRSA transmission of rapid PCR testing of patients admitted to critical care. J Hosp Infect 2007;65: 24e28.

20. Health Protection Agency. Surgical site infection in England. October 1997 to September 2005. London: Health Protection Agency; 2005.

21. Koopman PA. Confidence limits for the ratio of two binomial proportions. Biometrics 1984;40:513e517.

22. Gaynes RP, Culver DH, Horan TC, et al. Surgical site infection (SSI) rates in the United States, 1992e1998: the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System Basic SSI Risk Index. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33(Suppl. 1): S69eS77.

23. Konvalinka A, Errett L, Fong IW. Impact of treating Staphy- lococcus aureus nasal carriers on wound infections in car- diac surgery. J Hosp Infect 2006;64:162e168.

24. Trautmann M, Stecher J, Hemmer W, Luz K, Pankin HT. Intranasal mupirocin prophylaxis in elective surgery. A review of publishers studies. Chemother 2008;54:9e16.

25. Perl TM, Cullen JJ, Wenzel RP, et al. Intranasal mupirocin to prevent post-operative Staphylococcus aureus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1871e1877.

26. Reddy SL, Grayson AD, Smith G, Warwick R, Chalmers JA. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections fol- lowing cardiac surgery: incidence, impact and identifying adverse outcome traits. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31: 113e117.

27. Greig J, Edwards C, Wallis M, Jenks P, Cunningham R, Keenan J. Carriage of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among patients admitted with fractured neck of fe- mur. J Hosp Infect 2007;66:187e189.

28. Warren DK, Liao LR, Merz LR, Eveland M, Dunne Jr WM. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from nasal swab cultures by a real-time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:5578e5581.

29. Desjardins M, Guibord C, Lalonde B, Toye B, Ramotar K. Evaluation of the IDI-MRSA assay for the detection of meth- icillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from nasal and rectal specimens pooled in selective broth. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:1219e1223.

30. Wren MW, Carder C, Coen PG, Gant V, Wilson AP. Rapid mo- lecular detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:1604e1605.

130 S. Jog et al.

31. Bishop EJ, Grabsch EA, Ballard SA, et al. Concurrent analy- sis of nose and groin swab specimens by the IDI-MRSA PCR assay is comparable to analysis by individual-specimen PCR and routine culture assays for detection of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Mi- crobiol 2006;44:2904e2908.

32. Boyce JM. Preventing staphylococcal infections by eradicat- ing nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: proceeding with caution. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17:775e779.

33. Cookson BD. The emergence of mupirocin resistance: a chal- lenge to infection control and antibiotic prescribing prac- tice. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998;41:11e18.

Vigilancia Universal de MRSA (Robisek et al., 2007) y RT-PCR

• Vigilancia universal en un complejo de tres hospitales.

• Reducción significativa de las tasas de infección de MRSA en un 70 % en menos de dos años, en todas las categorías medidas: infecciones sanguíneas, del tracto urinario, de herida quirúrgica y respiratorias.

Control de MRSA: Vigilancia Universal