FACTORES MECÁNICOS EN Objetivos de PREPARACIONES … › unab › media › doc ›...

Transcript of FACTORES MECÁNICOS EN Objetivos de PREPARACIONES … › unab › media › doc ›...

D r . C l a u d i o G a n d a r i l l a s F .

FACTORES MECÁNICOS EN PREPARACIONES DENTARIAS

U n i v e r s i d a d A n d r é s B e l l o - F a c u l t a d d e o d o n t o l o g í a - V i ñ a d e l M a r

RESTAURACIONES

Lesiones de CariesLesiones No Cariosas

MalformacionesProblemas Estéticos

Reemplazo de restauracionesIatogrenia

Objetivos de restauraciones:

1. Restaurar forma/función y estética.

2. Promover la integridad de los tejidos duros y blandos de la cavidad oral.

3. Promover salud y bienestar de los pacientes.

Adecuado diagnósticoBiomaterialesTécnica clínica

Preparación dentaria

RESTAURACIONESEXITOSAS

Forma artificial que se da a un diente para poder reconstruirlo con materiales y técnicas adecuadas que devuelvan su función

dentro del aparato masticatorio.

Preparación Dentaria

Cavidad Muñón Planos radiculares Biseles

Asperización

Preparación Dentaria Tipos de Preparaciones / Restauraciones

ExtracoronariaIntracoronaria

OPERATORIA PROTESIS FIJA

Restauraciones de cobertura no completaRestauraciones Intracoronarias Restauraciones Extracoronarias

DIRECTAS INDIRECTAS

!

!

!

!

!

!

INDIRECTAS

Amalgamas

Resinas

Inlays

Onlays

Coronas

Carillas

RESTAURACIONES DENTARIAS

INDIRECTAS

Forma de Anclaje

DIRECTAS

Forma de Retención

!!

!!

• Eliminar todos los defectos y dar la protección necesaria a la pulpa dental.

• Situar los márgenes de la restauración de la forma más conservadora posible.

• Dar forma adecuada de modo que las fuerzas masticatorias sobre el diente,

restauración o ambos no produzcan fracturas ni desplacen la restauración.

• Permitir la aplicación estética y funcional de un material restaurador.

OBJETIVOS:

Preparación Dentaria Preparación Dentaria

Factores Biológicos

Factores MecánicosPrincipios biomecánicos

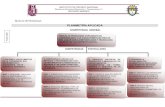

Planimetria cavitaria

Mecánica: Parte de la física que estudia el movimiento y el equilibrio de los cuerpos, así como de las fuerzas que los producen.

RETENCIÓN

Principio Biomecánico definido como:

Fuerzas que se oponen a la extrusión de la restauración a lo largo del eje de inserción de la restauración.

• Paredes axiales de una cavidad• Paredes axiales de un muñón• Paredes internas de conducto protésico• Anclajes complementarios

Dada por fricción o roce entre las paredes axiales de la preparación dentaria y la restauración:

RETENCIÓN

La Retención depende de:

• Conicidad/paralelismo de paredes contrapuestas• Longitud de paredes opuestas• Diámetro de la preparación• Retenciones auxiliares

La Retención es Potenciada por:

• Paredes largas, lisas y paralelas• Ángulos Marcados• Correcta correspondencia de superficies

¿Que otorga principalmente la retención en cavidades expulsivas?

El elemento esencial de la retención lo constituyen el paralelismo entre dos superficies dentarias verticales opuestas entre si que pertenecen a la misma preparación dentaria.

PARALELISMO ENTRE PAREDES

Paralelismo

FORMAS DE RETENCIÓN

Por retención (socavado)

FORMAS DE RETENCIÓN

Compresión

FORMAS DE RETENCIÓN

Profundización

FORMAS DE RETENCIÓN

/ Mortaja

! !

Cola de Milano

D M

Vista Oclusal

FORMAS DE RETENCIÓN

Principio biomecánico definido como toda FUERZA que se opone a la intrusión de la

restauración.

Lo otorgan las superficies de la preparación dentaria que no son paralelas a las fuerzas de intrusión (paredes oblicuas y perpendiculares)

SOPORTE

!

ANCLAJE

Lo que impide que una restauración se desaloje o se mueva de su posición sin estar sometida a cargas funcionales.

Depende principalmente de la Retención.

Lo que impide que una restauración se desaloje o se mueva de su posición bajo la acción de fuerzas funcionales o parafuncionales.

Este principio también se conoce como “estabilidad funcional”

ESTABILIDAD (RESISTENCIA) Fuerzas que actúan sobre los dientes

Comprensivas Traccionales Tangenciales

ESTABILIDAD (RESISTENCIA)Fuerzas que actúan sobre los dientes

f: fuerza masticatoria

ESTABILIDAD (RESISTENCIA)Fuerzas que actúan sobre los dientes

f: fuerza masticatoria

L = f tang. alfa

FUERZA LATERAL (L)

alfa=8f: fuerza=10 kg.

fuerza lateral = 70 kg.

Efecto Cuña

A mayor Altura cuspídea plano inclinado de mayor ángulo

Mayor posibilidad de fractura

Teoría de Robinson

Estudio de las tensiones con diferentes diseños cavitarios

Estudio del efecto cuña de las restauraciones sobre lo dientes:

Recubrimiento cuspídeoDisminución de la altura cuspídea.Ángulos diedros redondedos

FOTO

ELAS

TICI

DAD

542 d e n t a l m a t e r i a l s 2 3 ( 2 0 0 7 ) 539–548

(enamel and dentin) are automatically created in the form ofmasks by growing a threshold region on the entire stack ofscans (Fig. 1B). Using MIMICS STL+ module, enamel (Fig. 2A)and dentin were then separately converted into stereolithog-raphy files (STL, bilinear and interplane interpolation algo-rithm). Native STLs are improper for use in FEA because ofthe aspect ratio and connectivity of the triangles in these files.The REMESH module attached to MIMICS was therefore usedto automatically reduce the amount of triangles and simulta-neously improve the quality of the triangles while maintainingthe geometry (Fig. 2B). During remesh, the tolerance variationfrom the original data can be specified (quality of trianglesdoes not mean tolerance variation from the original data). Thequality is defined as a measure of triangle height/base ratioso that the file can be imported in the finite element anal-

Fig. 2 – (A) Stereolithography triangulated (STL) file ofenamel obtained through the STL+ module within MIMICS.The density and quality (aspect ratio and connectivity) ofthe triangles is not appropriate for use in finite elementanalysis. (B) Enamel STL file optimized for FEA using theREMESH module within MIMICS. Note the improvedtriangle shape and the intact geometry compared to Fig. 2Ain spite of a significant reduction in number of triangles.

Tabl

e2

–FE

Age

omet

ryan

dch

arac

teri

stic

sfo

rth

edi

ffer

ent

mod

els

Mod

ella

bel

Des

crip

tion

Spec

ific

feat

ure

sV

olu

met

ric

mes

h

No.

ofel

emen

tsa

No.

ofn

odes

a

NA

TIn

tact

nat

ura

ltoo

th(u

nre

stor

ed)

Man

dib

ula

rm

olar

1293

7427

223

CA

VM

OU

nre

stor

edto

oth

wit

hM

Op

rep

arat

ion

Occ

lusa

lwid

th:1

/2in

terc

usp

.wid

th;o

cclu

sald

epth

:>3

mm

;p

roxi

mal

dep

th:1

mm

abov

eC

EJ;d

ista

lmar

gin

alri

dge

inta

ct10

6817

2351

9

CA

VM

OD

Un

rest

ored

toot

hw

ith

MO

Dp

rep

arat

ion

Occ

lusa

lwid

th:1

/2in

terc

usp

.wid

th;o

cclu

sald

epth

:>3

mm

;p

roxi

mal

dep

th:1

mm

abov

eC

EJ95

826

2151

0

END

OM

OU

nre

stor

edto

oth

wit

hM

Op

rep

arat

ion

and

end

odon

tic

acce

ssp

rep

arat

ion

End

odon

tic

acce

ssca

vity

rem

ovin

gin

tact

wal

lwit

had

jace

nt

box.

1136

0325

554

END

OM

OD

Un

rest

ored

toot

hw

ith

MO

Dp

rep

arat

ion

and

end

odon

tic

acce

ssp

rep

arat

ion

End

odon

tic

acce

ssca

vity

rem

ovin

gin

tact

wal

lsw

ith

both

adja

cen

tbo

xes

1026

1223

432

CPR

Toot

hre

stor

edw

ith

MO

Dco

mp

osit

ere

stor

atio

nR

esto

rati

onsi

zesi

mila

rto

CA

V12

9374

2722

3

CER

Toot

hre

stor

edw

ith

MO

Dfe

ldsp

ath

icce

ram

icre

stor

atio

nR

esto

rati

onsi

zesi

mila

rto

CA

V12

9374

2722

3

aSt

one

base

excl

ud

ed.

d e n t a l m a t e r i a l s 2 3 ( 2 0 0 7 ) 539–548 543

ysis software package without generating any problem. Theremesh operations were also applied to the dentin STL. Seg-mentation of enamel and dentin may be accomplished by atrained operator in ca. 90 min (including remesh of the STLfiles).

Third, a strereolithography handling software (MAGICS 9.9,Materialise, Leuven Belgium) was used in order to reestab-lish the congruence of the interfacial mesh between enameland dentin (this congruence being lost during the previousremeshing process) using Boolean operations (addition, inter-

Fig. 3 – (A) Cross-sectional view of the enamel–dentin assembly as seen in MAGICS. Both enamel and dentin STLs share theexact same geometry at their interface (dentinoenamel junction). (B). Congruent enamel (white) and dentin (yellow) meshesalong with CAD objects used to simulate a stone base (cylinder) and different cavity designs (red inserts). Mesh congruencebetween the root portion and the stone base was obtained through a Boolean subtraction process (stone cylinder minusdentin). (C). Congruent STL parts of enamel (white) and dentin (yellow) resulting from Boolean intersections andsubstractions between the original enamel/dentin STLs and different CAD inserts (right side). The assembly of the differentparts result in five possible models (left side), i.e. the natural tooth (NAT), MO and MOD cavities (CAV), MO and MODendodontic access preparations (ENDO). The NAT model was also used to simulate a composite resin inlay (CPR) and aporcelain inlay (CER) by attributing different material properties to the enamel and dentin inserts (see Table 2).

section or subtraction of volumes). Once a congruent mesh atthe dentinoenamel junction was obtained (Fig. 3A), additionalBoolean operations with CAD objects (Fig. 3B and C) were usedto simulate a cylindrical fixation base (embedding the rootwithin 2 mm of the cementoenamel junction), as well as dif-ferent cavity preparations (MO and MOD cavities, endodonticaccess cavities) and restorations. The exact design and dimen-sions of the MO, MOD and endodontic access cavities aredescribed in Table 2. These successive restorative situationswere chosen because they reproduce existing experiments

ANALISIS DE ELEMENTO FINITO546 d e n t a l m a t e r i a l s 2 3 ( 2 0 0 7 ) 539–548

Fig. 6 – First principal stress distribution in four of the seven models studied. To allow for better comparison of the stresspattern, the MOD insert of enamel and dentin (model NAT) or the MOD ceramic restoration (model CER) were made invisible.Colors, tensile stresses; gray, compressive stresses. Note the similarity between NAT and CER.

approaches were proposed to access the inner anatomicaldetail without extrapolation and accelerate the productionof the models. Verdonschot et al. [13] might have been thefirst authors to describe the development of a 3D finite ele-ment model of a restored tooth based on a microscale CTdata-acquisition technique. The tooth was scanned after beingrestored with an MOD composite and the 3D geometry wasobtained through the stacking of traced 2D sections, stillinvolving a significant amount of manual work. An interest-ing semi-automated method was proposed [6–8] to generatesolid models of bones without internal boundaries (plain auto-matic volumetric mesh), then using the Hounsfield unit (HU)to attribute a specific Young’s modulus to each element basedon scan density. When applied to small structures like teeth(with thin anatomical details such as the enamel shell), thistechnique does not allow the fine control of internal bound-aries (e.g. dentinoenamel junction), the exact geometry ofwhich will have to follow the automatic volumetric meshingprocess.

The approach used in the present study suggests thatmaximum anatomical detail is obtained by surface/interface-based meshing using stereolithography (STL) surface data.The different parts of the model featuring different mechan-ical properties are identified first (segmentation process) andmeshed accordingly. Elements do not overlap the differentstructures but strictly follow the internal boundaries, resulting

in a smooth and very well controlled representation of inter-faces like the dentinoenamel junction (Fig. 3A). Significantadvantages, when using STLs, are the sophisticated visual-ization tools (shaded wireframe 3D views, section views etc.)and possibilities offered by the Boolean operations. The gen-eral principle of Boolean operations is that a new object can beformed by combining two 3D objects. Objects can be united,intersected or subtracted. When intersecting or subtractingtwo overlapping objects, a congruent mesh is assured at theinterface between the new objects. This property is essen-tial to assure the continuity of the resulting volumetric mesh.Boolean operations with predefined CAD objects (box, cylin-der, cone or inserts as in Fig. 3B) constitute an importantfeature. It allowed us to “digitally” simulate successive restora-tive procedures (Fig. 3C), unlike Verdonschot et al. [13] whohad to “physically” restore the tooth before scanning it. In thepresent study, the geometry of the unaltered tooth remains,allowing for direct comparison with the different experimen-tal conditions. The very user-friendly graphic interface allowsfor rapid modifications of the different parts and generationsof new STLs that can be instantly exported and volumetricallymeshed the FEA program. It must be pointed out that micro-CTis not suitable for human teeth in live patients. However, con-sidering that only 81 slices were necessary to generate thesevalid FEA models, one can easily foresee that the exponentialdevelopment of commercial dental CT-scanners, computer

544 d e n t a l m a t e r i a l s 2 3 ( 2 0 0 7 ) 539–548

Table 3 – Material properties

Elastic modulus (GPa) Poisson’s ratio

Enamel 84.1a 0.30b

Dentin 18.6c 0.31d

Composite 10.0e 0.24f

Ceramic 78.0g 0.28a

a Craig et al. [25].b Anusavice and Hojjatie [24].c McGuiness et al. [28].d Farah et al. [27].e Eldiwany et al. [26].f Nakayama et al. [29].g Data from manuftacturer of Creation-Willi Geller dental porcelain

(Klema, Meiningen, Austria).

[14–16], which will be used in the validation process of the FEAmodel (see Section 3). Two additional experimental conditionswere generated by attributing different material properties tothe enamel and dentin inserts included in model NAT: a com-posite resin inlay (CPR) and a feldspathic ceramic inlay (CER).The treatment of the STL files in MAGICS may be accomplishedby a trained operator in ca. 30–60 min per model (including allBoolean operations).

Fourth, the optimized STL files of the segmented enameland dentin parts were then imported in a finite element anal-ysis software package (MSC.Marc/MSC.Mentat, MSC.Software,Santa Ana, CA) for the generation of a volumetric mesh andattribution of material properties (Table 3). The triangulatedSTL files are ideal for automatic mesh generation using atetrahedral mesher (tetrahedron elements with pyramid-likeshape and 4 nodal points). This last step may be accomplishedby a trained operator in ca. 30–60 min per model (includingattribution of boundary conditions and 17 min to run the anal-ysis).

2.2. Boundary conditions, loadcase and dataprocessing

Fixed zero-displacement in the three spatial dimensions wasassigned to the nodes at the bottom surface of the stone base.The tooth and restorative materials were taken as bonded,which simulate usage of adhesive luting cements. A uniformlyramp loading was applied to the mesial cusps through a rigidbody, i.e. a 9.5-mm diameter ball positioned as close as possi-ble to the tooth (Fig. 4). The tooth was defined as deformablecontact body. Contact between these bodies was determinedautomatically by the FEA simulation during the static mechan-ical loadcase (no inertia effects) with a uniform stepping pro-cedure of 10 steps. A motion was applied to the rigid ball alongthe Z-axis through a negative velocity of 0.02 mm per step.Only one step was required to reach contact in both cusps. Themotion continued for the remaining steps to reach a total force100–200 N on the ball (depending on the model). The stress andstrain distributions were solved using the MSC.Marc solver. Asmentioned before, these specific boundary conditions, loadprotocol and configuration were chosen because they repro-duce existing experiments by Panitvisai and Messer [14], andJantarat et al. [15,16].

Fig. 4 – Load protocol and configuration as seen in Mentat,i.e. a nonlinear contact analysis between a rigid body(9.5-mm diameter load sphere moving along Z-axis againstthe tooth) and a deformable tooth (CAV MOD shown here).The widening of the cusps (!v) was calculated from theoutput values of displacement along the Y-axis for selectednodes near the cusp tip.

3. Results

The post-processing file was accessed through MENTAT toselect specific nodes on the buccal and lingual enamel nearthe cusp tip and to collect the values of displacement inthe Y direction for each loading step (Y+ denotes displace-ment in lingual direction and Y− in buccal direction). Theforce along the Z-axis on the rigid ball was also collectedfor each step. After the transfer of these data to a spread-sheet, the widening (deformation) of the cusp was calculated(by summing the displacement of each cusp) and plottedagainst the force along Z-axis on the ball (Fig. 5). As expectedin an elastic simulation, there is a quasi-linear relationshipbetween load and deformation. The progressive loss of toothsubstance (MO to MOD to ENDO) translates into a progres-sive loss of cuspal stiffness (decreased slope of the force vs.deformation plot). The unrestored tooth (NAT) and the toothwith the MOD ceramic inlay (CER) display the same con-duct (100% recovery of cuspal stiffness), while the more flex-ible composite inlay allowed for partial of recovery of cuspalstiffness.

ANALISIS DE ELEMENTO FINITO

Concepto de Ingraham

Preparaciones dentarias para incrustaciones metálicas de clase I y II que no protegen las cúspides favorecen la fractura dentaria

Concepto de Ingraham Concepto de IngrahamConcepto de Vigas

Tipos de vigas Viga simple apoyada

Viga fija y libre Viga a extremo libre

cantilever - voladizo

Viga empotrada en sus extremos

P3

Tensión máxima que resiste una viga:

Proporcional a su ancho en sentido horizontal

Proporcional al cuadrado de su espesor en sentido vertical

Resistencia de las vigas:

a b c

1x 2x4x

en Preparaciones DentariasAPLICACIÓN PRINCIPIOS BIOMECÁNICOS Tamaño cavitario y resistencia de paredes

• Cavidades conservadoras aumentan resistencia del remanente

• Resistencia de paredes: determina el tipo de restauración

• Concepto de esmalte sostenido idealmente (no valido para RC)

• Seguir la dirección de los prismas (ángulo cavo superficial).

a)

b)

c)

Ángulo Cavo Superficial

Ángulo Cervical FLEXIÓN DE PISO

• La flexión es mayor cuando el espesor dentinario es menor.

• Siempre deben existir puntos de

apoyo en tejido firme.• Piso cavitario plano.

dolor y/o fractura

FLEXIÓN DE PISO CONCLUSIÓN

• Siempre tener presente que una cavidad implica perdida de integridad dentaria.

• Capacidad de determinar mejor opción de tratamiento de acuerdo a la pérdida de tejido (intracoronaria, extracoronaria, recubrimiento cuspideo)

• Aplicar conceptos básicos de mecánica aplicados al diente al momento de tallar nuestra cavidad.

• Aplicar siempre lo aprendido en relación a las características cavitarias para cada tipo de restauración.

![Gps - Planimetria[1]](https://static.fdocuments.ec/doc/165x107/5695d3ad1a28ab9b029ec893/gps-planimetria1.jpg)