Datos de Los Videos Ignacio Ramonet

-

Upload

guerguerias1 -

Category

Documents

-

view

117 -

download

0

Transcript of Datos de Los Videos Ignacio Ramonet

Ignacio Ramonet

Ignacio Ramonet (Redondela, Pontevedra, 5 de mayo de 1943) es un periodista español establecido en Francia. Es una de las figuras principales del movimiento antiglobalización.1

Contenido

[ocultar]

1 Biografía 2 Obra 3 Véase también 4 Referencias 5 Enlaces externos

[editar] Biografía

Nacido en 1943, Ramonet creció en Tánger donde sus padres, republicanos españoles que huían de Franco, se instalaron en 1948. Estudió en la Universidad de Burdeos y regresó a Marruecos. En 1972 se trasladó a París, donde se inició como periodista y crítico cinematográfico.

Es doctor en Semiología e Historia de la Cultura por la École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) de París y catedrático de Teoría de la Comunicación en la Universidad Denis-Diderot (París-VII).

Especialista en geopolítica y estrategia internacional y consultor de la ONU, actualmente imparte clases en la Sorbona de París. Desde 1990 hasta 20082 fue director de la publicación mensual Le Monde Diplomatique y la bimensual Manière de voir.

Es cofundador de la organización no gubernamental Media Watch Global (Observatorio Internacional de los Medios de Comunicación) de la que es presidente.

Un editorial escrito en Le Monde Diplomatique durante 1997 dio lugar a la creación de ATTAC, cuya labor se dedicó originalmente a la defensa de la tasa Tobin. En la actualidad se dedica a la defensa de una gran variedad de causas de la izquierda política y tiene como presidente de honor a Ignacio Ramonet. Fue también uno de los promotores del Foro Social Mundial de Porto Alegre.

Es Doctor Honoris Causa de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, en España, y de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, en Argentina.

[editar] Obra

Ha sido galardonado en numerosas ocasiones y es autor de varios libros, la mayoría traducidos a diversas lenguas, entre los que destacan:

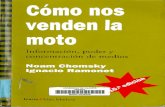

La Golosina visual, (1985 y 2000) Cómo nos venden la moto, (con Noam Chomsky; 1995) Il Pensiero Unico (con Fabio Giovannini y Giovanna Ricoveri; 1996) Nouveaux pouvoirs, nouveaux maîtres du monde (1996) Télévision et pouvoirs (1996) Un Mundo sin rumbo (1997) Internet, el mundo que viene (1998) Rebeldes, dioses y excluidos (con Mariano Aguirre; 1998) La tiranía de la comunicación (1999) Geopolitica i comunicació de final de mil-lenni (2000) Marcos, la dignidad rebelde (2001) Propagandas silenciosas o Guerras del Siglo XXI (2002) La Post-Television(2002) Abécédaire partiel et partial de la mondialisation, (con Ramón Chao y Wozniak;

2003) Irak, historia de un desastre (2004) ¿Qué es la globalización? 2004 (con Jean Ziegler, Joseph Stiglitz, Ha-Joon Chang,

René Passet y Serge Halimi) Fidel Castro: biografía a dos voces o Cien horas con Fidel (2006) La catástrofe perfecta (Le Krach Parfait) (2009)

[editar] Véase también

Attac

[editar] Referencias

1. ↑ Ramonet, Ignacio (2009). La catástrofe perfecta (2010 (Diario público) edición). por acuerdo con: Icaria editorial S.A y Éditions Galilée. pp. 228. B-20114-2010.

2. ↑ Mensaje de París | Le Monde diplomatique, edición peruana

[editar] Enlaces externos

Wikiquote alberga frases célebres de o sobre Ignacio Ramonet. El Quinto Poder por Ignacio Ramonet Página web de Le Monde Diplomatique Transcripción de una conferencia en español de Ignacio Ramonet sobre la relación

del poder y los medios de comunicación El latifundio de la información es una excelente metáfora. Publicado el : 2 Junio

2009 - 12:27 de la tarde . Radio Nederland por Ignacio Ramonet

Categorías: Nacidos en 1943 | Redondelanos | Periodistas de la provincia de Pontevedra | Sociólogos de España | Geopolítica | Críticos de la globalización | Escritores antiglobalización

Iniciar sesión / crear cuenta

Artículo Discusión

Leer Editar Ver historial

Portada Portal de la comunidad Actualidad Cambios recientes Páginas nuevas Página aleatoria Ayuda Donaciones Notificar un error

Imprimir/exportar

Crear un libro Descargar como PDF Versión para imprimir

Herramientas

Otros proyectos

En otros idiomas

Català Deutsch English Suomi Français Galego Italiano 日本語 Македонски Nederlands Norsk (bokmål) Polski Português 中文

Esta página fue modificada por última vez el 26 ago 2011, a las 13:35. El texto está disponible bajo la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución Compartir

Igual 3.0; podrían ser aplicables cláusulas adicionales. Lee terminos de uso para más información.Wikipedia® es una marca registrada de la Fundación Wikimedia, Inc., una organización sin animo de lucro.

Contacto

Ignacio RamonetFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Ignacio Ramonet, Salon du livre, Geneva (2011).

Ignacio Ramonet (born May 5, 1943, Redondela, Pontevedra Province) is a Spanish journalist and writer.

He was the editor-in-chief of Le Monde diplomatique from 1991 until March 2008.[1]

An editorial published by Ramonet on December 1997 in this magazine resulted in the launching of ATTAC. In addition, Ramonet is one of the founders of the NGO Media Watch Global, and currently he is president of this organization. Ramonet also frequently contributes to El País and participates in an advisory council to Telesur.

Contents

[hide]

1 Life 2 Ideology

o 2.1 Socialism 2.1.1 Fidel Castro

o 2.2 Against globalization and liberalism 3 Attac

o 3.1 James Tobin against Attac 4 Works 5 Articles 6 See also 7 External links and references

[edit] Life

Ramonet grew up in Tangier. He studied engineering at Bordeaux, Rabat and Paris, and he has been professor at Université Paris-VII.

Ignacio Ramonet participated in the Stock Exchange of Visions project in 2007.

[edit] Ideology

[edit] Socialism

Ramonet calls it a betrayal of socialism that some social democrat parties have chosen the third way between socialism and capitalism. [2]

[edit] Fidel Castro

The NGO Reporters without Borders had written about Ramonet's strong relationship with Fidel Castro. Ramonet denied this claim in 2002 [3] . In May 2004, Ramonet supported Castro in a direct television interview when Castro protested about the Forbes Magazine's list of country leaders wealth. Castro was number 7 on the list[4]. Syyskuussa 2006 Ramonet julkaisi kirjan Fidel Castro : Biografía a Dos Voces.[5]

In 2006, Ramonet praised "comrade Castro" in a series of articles,[6] and became his only authorised biographer.[7]

[edit] Against globalization and liberalism

Ramonet has called for autarky and for regulation, taxes and tariffs that reduce international trade. [2]

[edit] Attac

According to Ramonet, globalization and ultra-liberalism threaten the sovereignty of national states. In his December 1997 editorial "Disarming the markets" Ramonet accused globalization for the Asian economic crisis and for threatening the identity of national states. To counter this, he called for an NGO for promoting Tobin tax (i.e., Attac). [2]

[edit] James Tobin against Attac

Ramonet founded Attac to promote Tobin Tax by the Keynesian economist James Tobin. Tobin himself has accused Attac for misusing his name and said that he is a supporter of free trade, as do most other economists too, and of International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization — "everything that these movements are attacking. They're misusing my name." Tobin also says that he has nothing in common with Attac. [8]

[edit] Works

1981 : Le Chewing-gum des yeux (French: Chewing Gum for the Eyes) 1989 : La Communication victime des marchands 1995 : Cómo nos venden la moto, with Noam Chomsky 1996 : Nouveaux pouvoirs, nouveaux maîtres du monde (French: New Powers, New

World Masters) 1997 : Géopolitique du chaos (French: Geopolitics of Chaos) 1998 : Internet, el mundo que llega (Spanish: Internet, the Coming World) 1998 : Rebeldes, dioses y excluidos (Spanish: Rebels, Gods, and the Excluded), with

Mariano Aguirre 1999 : La Tyrannie de la communication (French: The Tyranny of Communication) 1999 : Geopolítica y comunicación de final de milenio (Spanish: Geopolitics and

Communication at the End of the Millennium) 2000 : La golosina visual 2000 : Propagandes silencieuses 2001 : Marcos, la dignité rebelle 2002 : La Post-Télévision 2002 : Guerres du XXIe siècle (Wars of the 21st Century) 2004 : Abécédaire partiel et partial de la mondialisation, with Ramón Chao and

Wozniak 2006: Fidel Castro: biografía a dos voces (Spanish: Fidel Castro: Biography with

Two Voices) also titled Cien horas con Fidel (One Hundred Hours with Fidel)

[edit] Articles

Set The Media Free by Ignacio Ramonet (2003)

[edit] See also

ATTAC Financial transaction tax Tobin tax

[edit] External links and references

1. ̂ To our readers2. ^ a b c Vilka är franska Attac? - Globaliseringskritikernas gurus, Johan Norberg,

Liberal Debatt 1-20013. ̂ [1], Le Monde Diplomatique, April 20024. ̂ http://www.lexpress.fr/info/quotidien/actu.asp?id=37945. ̂ ISBN 0-307-37653-26. ̂ Ignacio Ramonet: "Cuba's Future is Now", "Castro's Enviable Record" and "Viva

Fidel!" in Was Fidel Good for Cuba?, Foreign Policy, December 27, 2006 (pdf)7. ̂ Cuba’s revolution 50 years on, Financial Times, January 24 2009

8. ̂ "They Are Misusing My Name", an interview with James Tobin, Der Spiegel, September 2, 2001

Stock Exchange Of Visions: Visions of Ignacio Ramonet (Video Interviews)

This article about a Spanish writer is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it.

This article about a European journalist is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it.

View page ratingsRate this pageWhat's this?TrustworthyObjectiveCompleteWell-written

I am highly knowledgeable about this topic (optional) Categories: 1943 births | Living people | People from Pontevedra (province) | Spanish essayists | Spanish journalists | Galician writers | Media theorists | Anti-globalization writers | Spanish writer stubs | European journalist stubs

Log in / create account

Article Discussion

Read Edit View history

Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia

Interaction

Help About Wikipedia Community portal

Recent changes Contact Wikipedia

Toolbox

Print/export

Languages

Català Deutsch Español Français Galego Italiano Македонски Nederlands 日本語 Norsk (bokmål) Polski Português Suomi 中文

This page was last modified on 7 August 2011 at 05:07. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License;

additional terms may apply. See Terms of use for details.Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Contact us

Ignacio RamonetAller à : Navigation, rechercher

Ignacio Ramonet au salon du livre de Genève en 2011.

Ignacio Ramonet, né le 5 mai 1943 à Redondela (Galice, Espagne), est un sémiologue du cinéma et un journaliste, ancien directeur du mensuel Le Monde diplomatique. Il est actuellement directeur de l'édition espagnole du Monde diplomatique1 et président de l'Association Mémoire des luttes 2 . Il est également éditorialiste de politique internationale à l'agence Kyodo News (Tokyo), à l'agence Inter Press Service (IPS)3, à Radio Nederland, (Amsterdam), au quotidien Elefterotypia (Athènes) et au journal d'information numérique Hintergründe, Allemagne.

Sommaire

[masquer]

1 Biographie 2 Le fondateur d'ATTAC 3 Relations avec Fidel Castro 4 Récompenses 5 Ouvrages 6 Notes et références 7 Liens externes

Biographie[modifier]

Ignacio Ramonet a grandi à Tanger (Maroc) où ses parents, républicains espagnols fuyant le franquisme, se sont installés vers 1948. Après avoir obtenu une Maîtrise ès Lettres en France à l'Université Bordeaux III, il enseigne au Collège du Plateau (Salé, Maroc), puis au collège du Palais royal de Rabat où il a comme élève le futur roi Mohammed VI. Il

s'installe définitivement en France en 1972. Influencé par Roland Barthes et dirigé par Christian Metz, il soutient en 1981 à l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales un doctorat sur le rôle social du cinéma cubain. De 1975 à 2005, il enseigne la théorie de la communication au département de Cinéma, Communication, Information (CCI) de l' Université Paris-VII.

Critique de cinéma, il collabore aux Cahiers du Cinéma puis à Libération qui vient alors d'être créé par Serge July et Jean-Paul Sartre. Entré au mensuel Le Monde diplomatique en février 1973, il en est élu directeur de la rédaction et président du directoire en janvier 1990 ; réélu à l'unanimité à deux reprises (1996 et 2002), il demeurera directeur du Monde diplomatique jusqu'à mars 2008 4 ,5.

Il est également docteur honoris causa de l'université de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle et de l'Université de Córdoba (Argentine), et auteur de plusieurs livres de géopolitique et de critique des médias.

Le fondateur d'ATTAC[modifier]

Ignacio Ramonet a été le premier à définir le concept de Pensée unique dans un article de janvier 19956.

Il a été à l'origine de la création de l'association ATTAC dont il est Président d'honneur. En effet, dans un éditorial du Monde diplomatique de décembre 1997 intitulé Désarmer les marchés, il constate que la Mondialisation financière s'est créé son propre État, avec ses appareils, ses réseaux d'influence et ses moyens d'actions, mais que c'est un État complètement dégagé de toute société, qu'elle désorganise les économies nationales, méprise les principes démocratiques qui les fonde, presse les États à s'endetter, exige des entreprises qu'elles leur reverse des dividendes de plus en plus élevés, et fait régner partout l'insécurité. Il propose donc d'établir une taxe sur toutes les transactions financière, la taxe Tobin 7 et, pour y contribuer, il suggère de mettre en place une organisation non gouvernementale, l'« Association pour une taxe Tobin d'aide aux citoyens (ATTAC)».

Il a été également parmi les promoteurs du Forum social mondial de Porto Alegre, dont il a proposé le slogan : Un autre monde est possible. Pour ce qui concerne la société médiatique, il est le fondateur de l'ONG internationale Media Watch Global (Observatoire international des médias) et de sa version française, l'Observatoire français des médias. Il est aussi membre du comité de parrainage de la Coordination française pour la Décennie de la culture de paix et de non-violence.

Relations avec Fidel Castro[modifier]

Une controverse, alimentée notamment par Reporters sans frontières, existe quant à sa proximité avec Fidel Castro; informations qu’il a démenties8. En mai 2004, Ignacio Ramonet apporte son soutien à Fidel Castro en direct à la télévision alors que ce dernier proteste contre le classement que Forbes vient de publier : celui des fortunes des chefs d'État, où Fidel Castro apparaît en 7e position9. Il a publié en septembre 2006 : Fidel

Castro : Biografía a dos voces10. Ce livre, traduit en une vingtaine de langues, est une suite d'entretiens entre Ignacio Ramonet et Fidel Castro.

Récompenses[modifier]

Il a reçu plusieurs distinctions internationales :

le Prix Liber'Press au « meilleur journaliste de l'année », Girona (Espagne), 1999 le Prix Colombe d'Or au « meilleur journaliste étranger défenseur de la paix »,

Rome (Italie), 2000 le Prix au « meilleur journaliste défenseur des droits de l'homme », La Corogne

(Espagne), 2001 le Prix Rodolfo-Walsh de journalisme « pour sa trajectoire professionnelle »,

Université de La Plata (Argentine), 2003 le Prix de la Communication culturelle Nord-Sud, Rabat (Maroc), 2003 le Prix Turia de l'information, Valence (Espagne), 2004 le Prix Méditerranée de l'information, Naples (Italie), 2005 le Prix José Couso de la liberté de la presse, Ferrol (Espagne), 2006. le Prix international de la Liberté de Presse attribué par le journal algérien Al

Khabar, Alger, 2007. le Prix Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins "pour son constant apport à une meilleure

compréhension des relations sociales, politiques, économiques et culturelles des sociétés contemporaines", Santiago du Chili, 2009.

le Prix Antonio-Asensio de journalisme "pour sa lutte constante en faveur d'un monde plus juste et plus libre", Barcelone, 2010

Ouvrages[modifier]

Le Chewing-Gum des yeux, Alain Moreau éditeur, Paris, 1980 ; nouvelle édition modifiée et augmentée, sous le titre Propagandes silencieuses, 2000, cf. infra.

La communication victime des marchands, La Découverte, 1989. Como nos venden la moto, avec Noam Chomsky, Icaria, Barcelone, 1995. Nouveaux pouvoirs, nouveaux maîtres du monde, Fides, Montréal, 1996. Géopolitique du chaos, Galilée, 1997 ; réédition en « Folio », Gallimard, Paris,

1999. La tyrannie de la communication, Galilée, 1999, Folio, Gallimard, 2002. (Extraits) Propagandes silencieuses. Masses, télévision, cinéma, Galilée, 2000 ; réédition en

« Folio », Gallimard, 2003 Marcos, la dignité rebelle. Entretiens avec le sous-commandant Marcos, Galilée,

2001. Guerres du XXI e siècle - Peurs et menaces nouvelles, Galilée, 2002. Abécédaire partiel et partial de la mondialisation, avec Ramon Chao et Jacek

Woźniak, Plon, 2004. Irak : Histoire d'un désastre, Galilée, 2005. Fidel Castro, biographie à deux voix, Fayard, Paris, 2007. Guide du Paris rebelle, avec Ramon Chao, Plon, Paris, 2008.

Le Krach Parfait, Galilée, 2009. La Crisis del Siglo, Icaria, Barcelone, 2009. L'Explosion du journalisme. Des médias de masse à la masse de médias, Éditions

Galilée, Paris, 2011

Notes et références[modifier]

1. ↑ Adresse: calle Aparisi i Guijarro, n°5, 2; 46003 Valencia (Espagne) http://www.monde-diplomatique.es [archive]

2. ↑ http://www.medelu.org [archive]

3. ↑ http://ipsnoticias.net/ [archive]

4. ↑ « La succession d’Ignacio Ramonet » [archive], Les Amis du Monde diplomatique, février 20085. ↑ « À nos lecteurs » [archive], Le Monde diplomatique, février 20086. ↑ http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/1995/01/RAMONET/1144 [archive]

7. ↑ Ignacio Ramonet, « Désarmer les marchés » [archive], Le Monde Diplomatique, décembre 19978. ↑ « Anticastrisme primaire » [archive], Ignacio Ramonet, Le Monde diplomatique, avril 20029. ↑ « Cuba : Infortuné Fidel » [archive], Pauline Lecuit, L'Express, 16 mai 200610. ↑ Fidel Castro : Biografía a dos voces, Ignacio Ramonet, 2006, Debate, Madrid, 656 p., ISBN 978-

0-307-37653-4

Liens externes[modifier]

Articles

« Viva Brasil ! » , Ignacio Ramonet, Le Monde diplomatique, janvier 2003 « Le cinquième pouvoir » , Ignacio Ramonet, Le Monde diplomatique, octobre 2003

Entretiens audio

Avec Daniel Mermet (émission Là-bas si j'y suis) autour de son livre le Krach parfait (17 février 2009)

Avec Daniel Mermet (émission Là-bas si j'y suis) autour de son livre le Krach parfait (18 février 2009)

Avec Daniel Mermet (émission Là-bas si j'y suis, sur France Inter ) autour de son livre L'Explosion du journalisme (1er mars 2011)

Portail de l’altermondialisme

Portail de la presse écrite

Catégories : Journaliste espagnol | Géopoliticien | Personnalité de l'altermondialisme | Personnalité de Attac France | Élève de l'École des hautes études en sciences sociales | Étudiant de l'université de Bordeaux III | Personnalité galicienne | Docteur honoris causa | Naissance en 1943 | Naissance dans la province de Pontevedra | [+]

Créer un compte ou se connecter

Article Discussion

Lire Modifier Afficher l’historique

Accueil Portails thématiques Index alphabétique Article au hasard Contacter Wikipédia

Contribuer

Premiers pas Aide Communauté Modifications récentes Faire un don

Imprimer / exporter

Boîte à outils

Autres langues

Català Deutsch English Español Suomi Galego Italiano 日本語 Македонски Nederlands Norsk (bokmål) Polski Português 中文

Dernière modification de cette page le 18 juillet 2011 à 09:55. Droit d'auteur : les textes sont disponibles sous licence Creative Commons paternité

partage à l’identique ; d’autres conditions peuvent s’appliquer. Voyez les conditions

d’utilisation pour plus de détails, ainsi que les crédits graphiques. En cas de réutilisation des textes de cette page, voyez comment citer les auteurs et mentionner la licence.Wikipedia® est une marque déposée de la Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., organisation de bienfaisance régie par le paragraphe 501(c)(3) du code

Ferran Montesa, empresario, ha suscrito una alianza con una gran empresa de informática, situando la suya propia en una dimensión idónea para competir en los tiempos que corren. Este refuerzo le permitirá dedicar parte de su talento y capacidad a ejercer de director general de la edición española de Le Monde Diplomatique. ¿Quién podía sospechar que en su corazón latía un editor en busca de un destino? Que los dioses sean benevolentes con su temeridad. Alfons Cervera, escritor y periodista, acaba de publicar otro libro. Diario de la Frontera, como se titula, recoge casi un centenar de artículos publicados en el periódico Levante, paridos todos ellos con la calidez y riqueza literaria que identifican al autor. Un amplio fresco de personajes y hechos pintados por un buen novelista doblado de agudo gacetillero, o al rev

Tasa TobinLa tasa Tobin o ITF (Impuesto a las transacciones financieras)1 es una propuesta de impuesto sobre el flujo de capitales en el mundo sugerido a iniciativa del economista estadounidense James Tobin en el año 1971, quien recibió el Premio Nobel de Economía en 1981, cuya instauración a nivel internacional ha sido propuesta e impulsada por el movimiento ATTAC,2 y por personalidades como Ignacio Ramonet, cuya implantación está siendo considerada con motivo de la crisis económica de 2008-2010.3 4 El propio Tobin ha considerado que se ha abusado de su nombre y su idea.5 En 2011 se ha vuelto a demandar la creación de un impuesto a las transaciones financieras, tanto desde autores políticas y monetarias -Unión Europea- como desde ONG como Oxfam.6 7

Los movimientos por una globalización alternativa opinan que los ingresos que este impuesto produciría podrían ser una importante fuente de financiación para combatir la pobreza en el mundo, pero otros, en especial los liberales de la escuela austriaca lo consideran una medida intervencionista especialmente perniciosa al obstaculizar el libre comercio, perjudicando según ellos a los países más pobres y presentando enormes dificultades de recaudación, gestión y utilización de los fondos.8

Contenido

[ocultar]

1 Historia 2 La Tasa 3 Críticas 4 Véase también 5 Referencias 6 Enlaces externos

[editar] Historia

El 15 de agosto de 1971, por orden del presidente Richard M. Nixon, el dólar estadounidense dejó de ser convertible en lingotes de oro incluso para gobiernos y bancos centrales extranjeros. Fue el fin del sistema de Bretton Woods, y el golpe de gracia al patrón oro. Con la adopción de un sistema de tipos de cambio flotantes y el fin de los controles sobre los movimientos de capitales, Tobin sugirió un nuevo sistema para la estabilidad monetaria mundial y propuso que tal sistema debería incluir una tasa que gravara las transacciones comerciales internacionales.

La idea durmió en un cajón durante más de 20 años, rechazada por el propio Tobin, que decía haber sido malinterpretado. Sin embargo, en 1997, Ignacio Ramonet, editor de Le Monde Diplomatique, reimpulsó el debate sobre la creación de la Tasa Tobin y creó una asociación para promoverla: ATTAC (Asociación por la Tasación de las Transacciones y por la Ayuda a los Ciudadanos). La tasa se ha convertido en un asunto defendido por los grupos altermundistas y ha conseguido invadir el debate político en la calle y en algunos parlamentos, llegando a ser incluso defendida parcialmente por el ex presidente francés Jacques Chirac.9 Por otra parte, el recientemente creado Banco del Sur, iniciativa del presidente Hugo Chávez de Venezuela y el ex presidente Néstor Kirchner, contempla, para mantener su autonomía con respecto a los organismos financieros internacionales (Banco Mundial, FMI, BID, CAF, entre otros) su capitalización con ingresos provenientes de una tasa Tobin introducida a escala regional.10

[editar] La Tasa

La Tasa Tobin consiste en pagar un impuesto cada vez que se produce una operación de cambio entre divisas, para frenar el paso de una moneda a otra y para, en palabras de Tobin, "echar arena en los engranajes demasiado bien engrasados" de los mercados monetarios y financieros internacionales. La tasa debía ser baja, en torno al 0,1%, para penalizar solamente las operaciones puramente especulativas de ida y vuelta a muy corto plazo entre monedas, y no a las inversiones.

La Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Comercio y Desarrollo (UNCTAD) concluyó que la tasa Tobin permitiría recaudar 720.000 millones de dólares anuales, distribuibles a partes iguales entre los gobiernos recaudadores y los países más pobres. Por su parte, el PNUD afirma que con el 10% de la suma recaudada sería posible proporcionar atención

sanitaria a todos los habitantes del planeta, suprimir las formas graves de malnutrición y proporcionar agua potable a todo el mundo, y que con un 3%, se conseguiría reducir a la mitad la tasa de analfabetismo presente en la población adulta, universalizando asimismo la enseñanza primaria.

Aunque la tasa Tobin está orientada a la amplitud de transacciones comerciales internacionales, si consideramos reducir el espectro de su aplicación, desde la amplitud del comercio, de la economía real, al campo exclusivo de las transacciones financieras de carácter especulativo, se crearía una importante diferencia. Hay quien opina que la tasa Tobin devendría así en un instrumento de control de la actividad especulativa -basada en instrumentos financieros complejos, de alto riesgo y alta volatilidad. La crisis económica de 2008-2010, provocada por las inversiones de alto riesgo a largo plazo, financiadas con deuda a corto plazo, muestran que la tasa Tobin podría convertirse en un instrumento estabilizador que podría evitar crisis económicas.11 12

[editar] Críticas

Los liberales, entre otros, rechazan la idea porque afirman que perjudica especialmente a los países pobres. Esgrimen los siguientes motivos:

1. Estos movimientos ya están gravados en numerosos países. Imponer una tasa adicional supone aceptar que los gobiernos son incapaces de controlar la evasión fiscal con impuestos, por lo que una nueva tasa no es más que otra confiscación arbitraria. Además, en palabras de Samir Amin: Controlar la especulación es querer curar los síntomas sin ocuparse de las causas de la enfermedad...

2. Una hipótesis es que la pobreza nunca podrá resolverse con transferencias, porque la pobreza no es un problema de distribución sino de falta de producción. No está nada claro que los obstáculos financieros de la tasa Tobin, al final no fueran a resultar perjudiciales para los pobres. Por lo pronto, la inyección de las cantidades de capital de las que se habla provocaría una inflación catastrófica.

3. Existen numerosos problemas técnicos para recaudar este impuesto, así como para gestionar y repartir su producto, actividades que requerirían una enorme (y presumiblemente ineficiente) maquinaria burocrática.

4. El mercado de transacciones en divisas produce utilidades enormes a las instituciones financieras e individuos que participan en el mismo. La Tasa Tobin ataca estos movimientos de capital, obstaculizando el libre comercio y provocando un mayor aislamiento, algo que no necesitan precisamente los países pobres del mundo.

5. Muchos países del Tercer Mundo tienen ligadas sus débiles monedas al dólar, de manera que si un ciudadano de estos países vendiera sus productos, por ejemplo, a la Unión Europea tendría que cambiar, primero, los euros a dólares (pagando una vez la Tasa Tobin) y, luego, los dólares a la moneda local (pagando así dos veces la Tasa Tobin).

[editar] Véase también

Impuesto negativo sobre la renta Renta básica Ley Glass-Steagall de 1933 Fondos de alto riesgo o Hedge funds

[editar] Referencias

1. ↑ Conoce el ITF2. ↑ Resucita la Tasa Tobin, 29/8/20093. ↑ Brown cree que la 'tasa Tobin' será una realidad, Público -España-, 12/2/20104. ↑ Una hoja de ruta para la tasa Tobin, Jesús Lizcano Álvarez, El País - España-,

14/2/20105. ↑ El movimiento antiglobalización abusa de mi nombre, entrevista a James Tobin

para Der Spiegel, 3 de septiembre de 2001.6. ↑ Susana Ruíz, Oxfam, Vuelve la 'tasa Tobin', en versión 2.0, 21/201/2010 - El País7. ↑ ¿Ya demás de la tasa Tobin 2.0?, José Antonio García Saez, 1 de julio de 2011 -

Attac8. ↑ Pobreza a todo gas9. ↑ Los líderes mundiales buscan en Davos soluciones al subdesarrollo10. ↑ El Banco del Sur11. ↑ Brown cree que la 'tasa Tobin' será una realidad, Público -España-, 12/2/201012. ↑ Una hoja de ruta para la tasa Tobin, Jesús Lizcano Álvarez, El País - España-,

14/2/2010

[editar] Enlaces externos

Resucita la Tasa Tobin, 29/8/2009 ¿Qué es la tasa Tobin? , por Fabienne Dourson.

Categorías: Impuestos | Finanzas internacionales | Antiglobalización

Iniciar sesión / crear cuenta

Artículo Discusión

Leer Editar Ver historial

Portada Portal de la comunidad Actualidad Cambios recientes

Páginas nuevas Página aleatoria Ayuda Donaciones Notificar un error

Imprimir/exportar

Crear un libro Descargar como PDF Versión para imprimir

Herramientas

En otros idiomas

Català Dansk Deutsch English Esperanto Suomi Français עברית Italiano 日本語 한국어 Nederlands Polski Português Simple English Svenska

Esta página fue modificada por última vez el 17 ago 2011, a las 08:50. El texto está disponible bajo la Licencia Creative Commons Atribución Compartir

Igual 3.0; podrían ser aplicables cláusulas adicionales. Lee terminos de uso para más información.Wikipedia® es una marca registrada de la Fundación Wikimedia, Inc., una organización sin animo de lucro.

Contacto

Tobin tax

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaFor the more general category of "financial transaction taxes", see Financial transaction tax. For the more general category of "currency transaction taxes", see Currency transaction tax.

A Tobin tax, suggested by Nobel Laureate economist James Tobin, was originally defined as a tax on all spot conversions of one currency into another. The tax is intended to put a penalty on short-term financial round-trip excursions into another currency.

Tobin suggested his currency transaction tax in 1972 in his Janeway Lectures at Princeton, shortly after the Bretton Woods system of monetary management ended in 1971.[1] Prior to 1971, one of the chief features of the Bretton Woods system was an obligation for each country to adopt a monetary policy that maintained the exchange rate of its currency within a fixed value—plus or minus one percent—in terms of gold. Then, on August 15, 1971, United States President Richard Nixon announced that the United States dollar would no longer be convertible to gold, effectively ending the system. This action created the situation whereby the U.S. dollar became the sole backing of currencies and a reserve currency for the member states of the Bretton Woods system, leading the system to collapse in the face of increasing financial strain in that same year. In that context, Tobin suggested a new system for international currency stability, and proposed that such a system include an international charge on foreign-exchange transactions.

In 2001, in another context, just after "the nineties' crises in Mexico, Southeast Asia and Russia,"[2] which included the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, and the 1998 Russian financial crisis, Tobin summarized his idea:

The tax on foreign exchange transactions was devised to cushion exchange rate fluctuations. The idea is very simple: at each exchange of a currency into another a small tax would be levied - let's say, 0.5% of the volume of the transaction. This dissuades speculators as many investors invest their money in foreign exchange on a very short-term basis. If this money is suddenly withdrawn, countries have to drastically increase interest rates for their currency to still be attractive. But high interest is often disastrous for a national economy, as the nineties' crises in Mexico, Southeast Asia and Russia have proven. My tax would return some margin of manoeuvre to issuing banks in small countries and would be a measure of opposition to the dictate of the financial markets.[3][4][5][6][7]

Though James Tobin suggested the rate as "let's say 0.5%", in that interview setting, others have tried to be more precise in their search for the optimum rate.

Contents

[hide]

1 Concepts and definitionso 1.1 Tobin's concepto 1.2 Variations on Tobin tax idea

1.2.1 The Spahn tax

1.2.2 Special Drawing Rightso 1.3 Scope of the Tobin concept

2 Evaluating the Tobin tax as a Currency Transaction Tax (CTT)o 2.1 Are different players in the economy operating at cross purposes to each

other?o 2.2 Stability, volatility and speculation

2.2.1 The appeal of stability to many players in the world economy 2.2.2 Effect on volatility

2.2.2.1 Theoretical models 2.2.2.2 Empirical studies

2.2.3 Historical attempts to reduce speculation via fixed exchange rates

o 2.3 Is there an optimum Tobin tax rate?o 2.4 Is the tax easy to avoid?

2.4.1 Technical feasibility 2.4.2 How many nations are needed to make it feasible?

3 Evaluating the Tobin tax as a general Financial Transaction Tax (FTT)o 3.1 Sweden's experience in implementing Tobin taxes in the form of general

financial transaction taxes 3.1.1 Tobin tax proponents reaction to the Swedish experience

o 3.2 Who would gain and who would lose if the Tobin tax (FTT) were implemented?

3.2.1 Views of ABAC (APEC Business Advisory Council) expressed in open letter to IMF

3.2.2 Views of the ITUC/APLN (Asia-Pacific Labour Network) expressed in their statement to the 2010 APEC Economic Leaders Meeting

3.2.3 Would 'regular investors like you and me' lose? 3.2.3.1 Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street

Bill 3.2.4 Would there be net job losses if a FTT tax was introduced?

o 3.3 Is there an optimum tax rate?o 3.4 Political opinion

3.4.1 Tobin tax proponents response to empirical evidence on volatility

3.4.2 Should speculators be encouraged, penalized or dissuaded?o 3.5 Questions of volatility

4 Comparing Currency Transaction Taxes (CTT) and Financial Transaction Taxes (FTT)

o 4.1 Research evidenceo 4.2 Practical considerations

5 Original idea and alter-globalization movement 6 Tobin tax proposals and implementations around the world

o 6.1 Sweden's experience with financial transaction taxes 6.1.1 Tobin tax proponents reaction to the Swedish experience

o 6.2 United Kingdom experience with stock transaction tax (Stamp Duty)

o 6.3 Sterling Stamp Duty - a currency transactions tax proposed for pound sterling

o 6.4 Multinational proposals 6.4.1 European idea for a 'first Euro tax' 6.4.2 Support in some G20 nations 6.4.3 The feasibility of gradual implementation of the FTT, beginning

with a few EU nations 6.4.3.1 Two simultaneous taxes considered in the European

Union 6.4.4 Latin America - Bank of the South 6.4.5 UN Global Tax

7 Support and opposition 8 See also 9 References 10 Further reading 11 External links

Concepts and definitions

Tobin's concept

James Tobin's purpose in developing his idea of a currency transaction tax was to find a way to manage exchange-rate volatility. In his view, "currency exchanges transmit disturbances originating in international financial markets. National economies and national governments are not capable of adjusting to massive movements of funds across the foreign exchanges, without real hardship and without significant sacrifice of the objectives of national economic policy with respect to employment, output, and inflation.”[1]

Tobin saw two solutions to this issue. The first was to move “toward a common currency, common monetary and fiscal policy, and economic integration.”[1] The second was to move “toward greater financial segmentation between nations or currency areas, permitting their central banks and governments greater autonomy in policies tailored to their specific economic institutions and objectives.”[1] Tobin’s preferred solution was the former one but he did not see this as politically viable so he advocated for the latter approach: “I therefore regretfully recommend the second, and my proposal is to throw some sand in the wheels of our excessively efficient international money markets.”[1]

Tobin’s method of “throwing sand in the wheels” was to suggest a tax on all spot conversions of one currency into another, proportional to the size of the transaction. He said:

It would be an internationally agreed uniform tax, administered by each government over its own jurisdiction. Britain, for example, would be responsible for taxing all inter-currency transactions in Eurocurrency banks and brokers located in London, even when sterling was not involved. The tax proceeds could appropriately be paid into the IMF or World Bank.

The tax would apply to all purchases of financial instruments denominated in another currency---from currency and coin to equity securities. It would have to apply, I think, to all payments in one currency for goods, services, and real assets sold by a resident of another currency area. I don't intend to add even a small barrier to trade. But I see offhand no other way to prevent financial transactions disguised as trade.[1]

In the development of his idea, Tobin was influenced by the earlier work of John Maynard Keynes on general financial transaction taxes:

I am a disciple of Keynes, and he, in his famous chapter XII of the General Theory on Employment Interest and Money, had already prescribed a tax on transactions, with the aim of linking investors to their actions in a lasting fashion. In 1971 I transferred this idea to exchange markets.[3][4]

Keynes' concept stems from 1936 when he proposed that a transaction tax should be levied on dealings on Wall Street, where he argued that excessive speculation by uninformed financial traders increased volatility. For Keynes (who was himself a speculator) the key issue was the proportion of 'speculators' in the market, and his concern that, if left unchecked, these types of players would become too dominant.[8] Keynes writes:

Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the situation is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation. (,[8] p. 104)

The introduction of a substantial government transfer tax on all transactions might prove the most serviceable reform available, with a view to mitigating the predominance of speculation over enterprise in the United States. (,[8] p. 105)

Variations on Tobin tax idea

The Spahn tax

Main article: Spahn tax

According to Paul Bernd Spahn in 1995, "Analysis has shown that the Tobin tax as originally proposed is not viable and should be laid aside for good." Furthermore, he said:

"...it is virtually impossible to distinguish between normal liquidity trading and speculative "noise" trading. If the tax is generally applied at high rates, it will severely impair financial operations and create international liquidity problems, especially if derivatives are taxed as well. A lower tax rate would reduce the negative impact on financial markets, but not mitigate speculation where expectations of an exchange rate change exceed the tax margin."[9]

Spahn suggested an alternative involving

"...a two-tier rate structure consisting of a low-rate financial transactions tax, plus an exchange surcharge at prohibitive rates as a piggyback. The latter would be dormant in times of normal financial activities, and be activated only in the case of speculative attacks. The mechanism allowing the identification of abnormal trading in world financial markets would make reference to a "crawling peg" with an appropriate exchange rate band. The exchange rate would move freely within this band without transactions being taxed. Only transactions effected at exchange rates outside the permissible range would become subject to tax. This would automatically induce stabilizing behavior on the part of market participants."[9]

Special Drawing Rights

On September 19, 2001, retired speculator George Soros put forward a proposal, Special Drawing Rights or SDRs that the rich countries would pledge for the purpose of providing international assistance, without necessarily dismissing the Tobin tax idea. He stated, "I think there is a case for a Tobin tax ... (but) it is not at all clear to me that a Tobin tax would reduce volatility in the currency markets. It is true that it may discourage currency speculation but it would also reduce the liquidity of the marketplace." [10]

Scope of the Tobin concept

The term "Tobin tax" has sometimes been used interchangeably with a specific currency transaction tax (CTT) in the manner of Tobin's original idea, and other times it has been used interchangeably with the various different ideas of a more general financial transaction tax (FTT). In both cases, the various ideas proposed have included both national and multinational concepts.

A 2001 example of its association with the specific currency transaction tax is shown here:

"The concept of a Tobin tax has experienced a resurgence in the discussion on reforming the international financial system. In addition to many legislative initiatives in favour of the Tobin tax in national parliaments, possible ways to introduce a Tobin-style currency transaction tax (CTT) are being scrutinised by the United Nations."[11]

A 2009 example of its association with a general financial transaction tax is shown here:

"European Union leaders urged the International Monetary Fund on Friday to consider a global tax on financial transactions in spite of opposition from the US and doubts at the IMF itself. In a communiqué issued after a two-day summit, the EU’s 27 national leaders stopped short of making a formal appeal for the introduction of a so-called “Tobin tax” but made clear they regarded it as a potentially useful revenue-raising instrument."[12]

Evaluating the Tobin tax as a Currency Transaction Tax (CTT)

See also: Currency transaction tax

See also Evaluating the Tobin tax as a general Financial Transaction Tax

Are different players in the economy operating at cross purposes to each other?

In 1994, Canadian economist Rodney Schmidt noted that

in two-thirds of all the outright forward and [currency] swap transactions, the money moved into another currency for fewer than seven days. In only 1 per cent did the money stay for as long as one year. While the volatile exchange rates caused by all this rapid movement posed problems for national economies, it was the bread and butter of those playing the currency markets. Without constant fluctuations in the currency markets, Schmidt noted, there was little opportunity for profit.[13]

This certainly seemed to suggest the interests of currency traders and the interests of ordinary citizens [in national economies] were operating at cross-purposes.[13]

Schmidt also noted another interesting aspect of the foreign- exchange market: The dominant players were the private banks, which had huge pools of capital and access to information about currency values. Since much of the market involved moving large sums of money (typically in the tens of millions of dollars) for very short periods of time (often less than a day), banks were perfectly positioned to participate. Among swap transactions, which represented a major chunk of the foreign exchange market, 86 per cent of the transactions were actually between banks.[13]

Stability, volatility and speculation

The appeal of stability to many players in the world economy

In 1972, Tobin examined the global monetary system that remained after the Bretton Woods monetary system was abandoned. This examination was subsequently revisited by other analysts, such as Ellen Frank, who, in 2002 wrote: "If by globalization we mean the determined efforts of international businesses to build markets and production networks that are truly global in scope, then the current monetary system is in many ways an endless headache whose costs are rapidly outstripping its benefits."[14] She continues with a view on how that monetary system stability is appealing to many players in the world economy, but is being undermined by volatility and fluctuation in exchange rates: "Money scrambles around the globe in quest of the banker’s holy grail – sound money of stable value – while undermining every attempt by cash-strapped governments to provide the very stability the wealthy crave."[14]

Frank then corroborates Tobin's comments on the problems this instability can create (e.g. high interest rates) for developing countries such as Mexico (1994), countries in South East Asia (1997), and Russia (1998).[2] She writes, "Governments of developing countries try to

peg their currencies, only to have the peg undone by capital flight. They offer to dollarize or euroize, only to find themselves so short of dollars that they are forced to cut off growth. They raise interest rates to extraordinary levels to protect investors against currency losses, only to topple their economies and the source of investor profits. ... IMF bailouts provide a brief respite for international investors but they are, even from the perspective of the wealthy, a short-term solution at best ... they leave countries with more debt and fewer options."[14]

Effect on volatility

One of the main economic hypotheses raised in favor of financial transaction taxes is that such taxes reduce return volatility, leading to an increase of long-term investor utility or more predictable levels of exchange rates. The impact of such a tax on volatility is of particular concern because the main justification given for this tax by Tobin was to improve the autonomy of macroeconomic policy by curbing international currency speculation and its destabilizing effect on national exchange rates.[1] Economist Korkut Erturk states:

if the Tobin Tax is not stabilizing, then much of the rest of the discussion on its feasibility and other related issues are probably moot.[15]

Theoretical models

Most studies of the likely impact of the Tobin tax on financial markets volatility have been theoretical—researches conducted laboratory simulations or constructed economic models. Some of these theoretical studies have concluded that a transaction tax could reduce volatility by crowding out speculators[16] or eliminating individual 'noise traders'[17] but that it 'would not have any impact on volatility in case of sufficiently deep global markets such as those in major currency pairs,[15] unlike in case of less liquid markets, such as those in stocks and (especially) options, where volatility would probably increase with reduced volumes.[18][19] Behavioral finance theoretical models, such as those developed by Wei and Kim (1997)[20] or Westerhoff and Dieci (2004)[21] suggest that transaction taxes can reduce volatility, at least in the foreign exchange market. In contrast, some papers find a positive effect of a transaction tax on market volatility.[22][23] Lanne and Vesala (2006) argue that a transaction tax "is likely to amplify, not dampen, volatility in foreign exchange markets", because such tax penalises informed market participants disproportionately more than uninformed ones, leading to volatility increases.[24]

Empirical studies

In most of the available empirical studies however, no statistically significant causal link has been found between an increase in transaction costs (transaction taxes or government-controlled minimum brokerage commissions) and a reduction in volatility—in fact a frequent unintended consequence observed by 'early adopters' after the imposition of a financial transactions tax (see Werner, 2003)[25] has been an increase in the volatility of stock market returns, usually coinciding with significant declines in liquidity (market volume) and thus in taxable revenue (Umlauf, 1993).[26]

For a recent evidence to the contrary, see, e.g., Liu and Zhu (2009),[27] which may be affected by selection bias given that their Japanese sample is subsumed by a research conducted in 14 Asian countries by Hu (1998),[28] showing that "an increase in tax rate reduces the stock price but has no significant effect on market volatility". As Liu and Zhu (2009) point out, [...] the different experience in Japan highlights the comment made by Umlauf (1993) that it is hazardous to generalize limited evidence when debating important policy issues such as the STT [securities transaction tax] and brokerage commissions."

See also "Tobin tax proponents response to empirical evidence on volatility"

Historical attempts to reduce speculation via fixed exchange rates

Matthew Sinclair, Research Director of TaxPayers' Alliance, notes that

one reason why few have supported a Tobin tax is that worries about foreign exchange speculation have slowly subsided as more countries have moved towards floating exchange rates, which do more to limit the potential for exchange rate speculation than a Tobin tax possibly could. Attempts to fix rates such as – in the 1980s and 1990s – the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) meant that we got large and sudden movements in exchange rates when speculators sensed that a peg could not be maintained, rather than the more fluid shifts of today.[29]

Is there an optimum Tobin tax rate?

When James Tobin was interviewed by Der Spiegel in 2001, the tax rate he suggested was 0.5%.[4][5][6] His use of the phrase "let's say" ("sagen wir") indicated that he was not, at that point, in an interview setting, trying to be precise. Others have tried to be more precise or practical in their search for the Tobin tax rate.

Tax rates of the magnitude of 0.1%-1% have been proposed by normative economists, without addressing how practicable these would be to implement. In positive economics studies however, where due reference was made to the prevailing market conditions, the resulting tax rates have been significantly lower.[citation needed]

According to Garber (1996), competitive pressure on transaction costs (spreads) in currency markets has reduced these costs to fractions of a basis point. For example the EUR.USD currency pair trades with spreads as tight as 1/10 of a basis point, i.e. with just a 0.00001 difference between the bid and offer price, so "a tax on transactions in foreign exchange markets imposed unilaterally, 6/1000 of a basis point (or 0.00006%) is a realistic maximum magnitude."[30] Similarly Shvedov (2004) concludes that "even making the unrealistic assumption that the rate of 0.00006% causes no reduction of trading volume, the tax on foreign currency exchange transactions would yield just $4.3 billion a year, despite an annual turnover in dozens of trillion dollars.[31]

Accordingly, one of the modern Tobin tax versions, called the Sterling Stamp Duty, sponsored by certain UK charities, has a rate of 0.005% "in order to avoid market

distortions", i.e., 1/100 of what Tobin himself envisaged in 2001. Sterling Stamp Duty supporters argue that this tax rate would not adversely affect currency markets and could still raise large sums of money.[32]

The same rate of 0.005% was proposed for a currency transactions tax (CTT) in a report prepared by Rodney Schmidt for The North-South Institute (a Canadian NGO whose "research supports global efforts to [..] improve international financial systems and institutions"),.[33] Schmidt (2007) used the observed negative relationship between bid-ask spreads and transactions volume in foreign exchange markets to estimate the maximum "non-disruptive rate" of a currency transaction tax. A CTT tax rate designed with a pragmatic goal of raising revenue for various development projects, rather than to fulfill Tobin's original goals (of "slowing the flow of capital across borders" and "preventing or managing exchange rate crises"), should avoid altering the existing "fundamental market behavior", and thus, according to Schmidt, must not exceed 0.00005, i.e., the observed levels of currency transactions costs (bid-ask spreads).[34]

Assuming that all currency market participants incur the same maximum level of transaction costs (the full cost of the bid-ask spread), as opposed to earning them in their capacity of market makers, and assuming that no untaxed substitutes exist for spot currency markets transactions (such as currency futures and currency exchange traded funds), Schmidt (2007) finds that that a CTT rate of 0.00005 would be nearly volume-neutral, reducing foreign exchange transaction volumes by only 14%. Such volume-neutral CTT tax would raise relatively little revenue though, estimated at around $33 bn annually, i.e., an order of magnitude less than the "carbon tax [which] has by far the greatest revenue-raising potential, estimated at $130-750 bn annually." The author warns however that both these market-based revenue estimates "are necessarily speculative", and he has more confidence in the revenue-raising potential of "The International Finance Facility (IFF) and International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm)."[34]

In 2000, a representative of another "pro-Tobin tax" non-governmental organization stated that Tobin's idea was

to ‘throw some sand in the wheels’ of speculative flows. For a currency transaction to be profitable [to the speculator], the change in value of the currency must be greater than the proposed tax. Since speculative currency trades occur on much smaller margins, the Tobin Tax would reduce or eliminate the profits and, logically, the incentive to speculate. The tax is designed to help stabilize exchange rates by reducing the volume of speculation. And it is set deliberately low so as not to have an adverse effect on trade in goods and services or long-term investments.[35]

Is the tax easy to avoid?

Technical feasibility

Although Tobin had said his own tax idea was unfeasible in practice, Joseph Stiglitz, former Senior Vice President and Chief Economist of the World Bank, said, on October 5,

2009, that modern technology meant that was no longer the case. Stiglitz said, the tax is "much more feasible today" than a few decades ago, when Tobin recanted.[36]

However, on November 7, 2009, at the G20 finance ministers summit in Scotland, Dominique Strauss-Khan, head of the International Monetary Fund, said "transactions are very difficult to measure and so it's very easy to avoid a transaction tax."[37]

Nevertheless in early December 2009, economist Stephany Griffith-Jones agreed that the "greater centralisation and automisation of the exchanges' and banks' clearing and settlements systems ... makes avoidance of payment more difficult and less desirable."[38]

In January, 2010, feasibility of the tax was supported and clarified by researchers Rodney Schmidt, Stephan Schulmeister and Bruno Jetin who noted “it is technically easy to collect a financial tax from exchanges ... transactions taxes can be collected by the central counterparty at the point of the trade, or automatically in the clearing or settlement process."[39][40] (All large-value financial transactions go through three steps. First dealers agree to a trade; then the dealers’ banks match the two sides of the trade through an electronic central clearing system; and finally, the two individual financial instruments are transferred simultaneously to a central settlement system. Thus a tax can be collected at the few places where all trades are ultimately cleared or settled.)[40][41]

When presented with the problem of speculators shifting operations to offshore tax havens, a representative of a “pro Tobin tax” NGO argued as follows:

Agreement between nations could help avoid the relocation threat, particularly if the tax were charged at the site where dealers or banks are physically located or at the sites where payments are settled or ‘netted’. The relocation of Chase Manhattan Bank to an offshore site would be expensive, risky and highly unlikely – particularly to avoid a small tax. Globally, the move towards a centralized trading system means transactions are being tracked by fewer and fewer institutions. Hiding trades is becoming increasingly difficult. Transfers to tax havens like the Cayman Islands could be penalized at double the agreed rate or more. Citizens of participating countries would also be taxed regardless of where the transaction was carried out.[35]

Based on digital technology, a new form of taxation, levied on bank transactions, was successfully used in Brazil from 1993 to 2007 and proved to be evasion-proof, more efficient and less costly than orthodox tax models. In his book, Bank transactions: pathway to the single tax ideal, Marcos Cintra carries out a qualitative and quantitative in-depth comparison of the efficiency, equity and compliance costs of a bank transactions tax relative to orthodox tax systems, and opens new perspectives for the use of modern banking technology in tax reform across the world.[42]

See also: Currency transaction report, Money Laundering Control Act, Bank Secrecy Act, Suspicious activity report, Money laundering, Structuring, and Electronic trading

How many nations are needed to make it feasible?

There has been debate as to whether one single nation could unilaterally implement a "Tobin tax." Speaking to this question, Schmidt states,

"It is possible for a single country to apply a securities transaction tax unilaterally without significant capital flight to exchanges in other jurisdictions. There are many examples of such taxes already in existence. Britain levies a "Stamp Duty", a 0.5% tax on purchases of shares of UK companies whether the transaction occurs in the UK or overseas. Such specific financial transaction taxes exist in Austria, Greece, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Hong Kong, China and Singapore. The state of New York levies a stamp duty on trades taking place on both the New York Stock Exchange and on NASDAQ."[41]

In the year 2000, "eighty per cent of foreign-exchange trading [took] place in just seven cities. Agreement [to implement the tax] by [just three cities,] London, New York and Tokyo alone, would capture 58 per cent of speculative trading."[35]

Evaluating the Tobin tax as a general Financial Transaction Tax (FTT)

See also: Financial transaction tax and Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill

Sweden's experience in implementing Tobin taxes in the form of general financial transaction taxes

In July, 2006, analyst Marion G. Wrobel examined the actual international experiences of various countries in implementing financial transaction taxes.[43] Wrobel's paper highlighted the Swedish experience with financial transaction taxes. In January 1984, Sweden introduced a 0.5% tax on the purchase or sale of an equity security. Thus a round trip (purchase and sale) transaction resulted in a 1% tax. In July 1986 the rate was doubled. In January 1989, a considerably lower tax of 0.002% on fixed-income securities was introduced for a security with a maturity of 90 days or less. On a bond with a maturity of five years or more, the tax was 0.003%.

The revenues from taxes were disappointing; for example, revenues from the tax on fixed-income securities were initially expected to amount to 1,500 million Swedish kroner per year. They did not amount to more than 80 million Swedish kroner in any year and the average was closer to 50 million.[44] In addition, as taxable trading volumes fell, so did revenues from capital gains taxes, entirely offsetting revenues from the equity transactions tax that had grown to 4,000 million Swedish kroner by 1988.[45]

On the day that the tax was announced, share prices fell by 2.2%. But there was leakage of information prior to the announcement, which might explain the 5.35% price decline in the 30 days prior to the announcement. When the tax was doubled, prices again fell by another 1%. These declines were in line with the capitalized value of future tax payments resulting

from expected trades. It was further felt that the taxes on fixed-income securities only served to increase the cost of government borrowing, providing another argument against the tax.

Even though the tax on fixed-income securities was much lower than that on equities, the impact on market trading was much more dramatic. During the first week of the tax, the volume of bond trading fell by 85%, even though the tax rate on five-year bonds was only 0.003%. The volume of futures trading fell by 98% and the options trading market disappeared. On 15 April 1990, the tax on fixed-income securities was abolished. In January 1991 the rates on the remaining taxes were cut in half and by the end of the year they were abolished completely. Once the taxes were eliminated, trading volumes returned and grew substantially in the 1990s.

Tobin tax proponents reaction to the Swedish experience

The Swedish experience of a transaction tax was with purchase or sale of equity securities, fixed income securities and derivatives. In global international currency trading, however, the situation could, some argue, look quite different. In 2000, Round argued as follows:

[The Tobin tax] could boost world trade by helping to stabilize exchange rates. Wildly fluctuating rates play havoc with businesses dependent on foreign exchange as prices and profits move up and down, depending on the relative value of the currencies being used. When importers and exporters can’t be certain from one day to the next what their money is worth, economic planning – including job creation – goes out the window. Reduced exchange-rate volatility means that businesses would need to spend less money ‘hedging’ (buying currencies in anticipation of future price changes), thus freeing up capital for investment in new production.[35]

Wrobel's studies do not address the global economy as a whole, as James Tobin did when he spoke of "the nineties' crises in Mexico, South East Asia and Russia,"[7][46] which included the 1994 economic crisis in Mexico, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, and the 1998 Russian financial crisis.

Who would gain and who would lose if the Tobin tax (FTT) were implemented?

See also: Financial transaction tax and Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill

Views of ABAC (APEC Business Advisory Council) expressed in open letter to IMF

The APEC Business Advisory Council, the business representatives' body in APEC, which is the forum for facilitating economic growth, cooperation, trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific region, expressed its views in a letter to the IMF on 15 February 2010. The APEC Business Advisory Council stated:

We believe that imposition of a global tax is an inappropriate response and a further burden to industries, especially small and medium enterprises, and consumers in the wake of the global financial crisis. We also believe that the proposals under consideration would be harmful for a range of additional reasons, including the practical challenges of implementing any such tax.[47]

In addition, ABAC expressed further concerns in the letter:-

Key to the APEC agenda is reduction of transaction costs. The proposal is directly counterproductive to this goal.

It would have a very significant negative impact on real economic recovery, as these additional costs are likely to further reduce financing of business activities at a time when markets remain fragile and prospects for the global economy are still uncertain.

Industries and consumers as a whole would be unfairly penalized. It would further weaken financial markets and reduce the liquidity, particularly in

the case of illiquid assets. Effective implementation would be virtually impossible, especially as opportunities

for cross-border arbitrage arise from decisions of certain jurisdictions not to adopt the tax or to exempt particular activities.

There is no global consensus why a tax is needed and what the revenue would be used for, and therefore no understanding how much is needed. Any consequential tax would need to be supported by clear consensus for its application.

Note - APEC's 21 Member Economies are Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, China, Indonesia, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, The Republic of the Philippines, The Russian Federation, Singapore, Chinese Taipei, Thailand, United States of America, Viet Nam.

Views of the ITUC/APLN (Asia-Pacific Labour Network) expressed in their statement to the 2010 APEC Economic Leaders Meeting

The International Trade Union Confederation/Asia-Pacific Labour Network (ITUC/APLN), the informal trade union body of the Asia-Pacific, supported the Tobin Tax in their Statement to the 2010 APEC Economic Leaders Meeting. The representatives of APEC's national trade unions centers also met with the Japanese Prime Minister, Naoto Kan, the host Leader of APEC for 2010, and called for the Prime Minister's support on the Tobin Tax.[48]

The ITUC/APLN stated:

APEC Leaders should support measures that will downsize the financial sector and return it to its legitimate function of serving the real economy. Instead of fiscal austerity policies and increased expenditure cuts APEC economies should exploit new sources of finance, such as the Financial Transactions Tax (FTT), and raise more revenue with progressive tax systems.[48]

The ITUC shares its support for Tobin Tax with the Trade Union Advisory Council (TUAC), the official OECD trade union body, in a research[49] on the feasibility, strengths and weaknesses of a potential Tobin Tax. ITUC, APLN and TUAC refer to Tobin Tax as the Financial Transactions Tax.

Would 'regular investors like you and me' lose?

An economist speaking out against the common belief that investment banks would bear the burden of a Tobin tax is Simon Johnson, Professor of Economics at the MIT and a former Chief Economist at the IMF, who in a BBC Radio 4 interview discussing banking system reforms presented his views on the Tobin tax

Evan Davis, BBC Radio 4:

There are various ideas around, aren't there, one of them is a Tobin tax, it's been associated with the [British] Prime Minister—a tax on global financial transactions. Is that a response, do you think, to the problems created by large banks and big bail-outs?

Prof. Simon Johnson:

I think it's hmm... partially a response, or an attempt to respond, that's not my preferred [...] approach to the problem, I think that would lead to a lot of distortions, a lot of moving of activities offshore. If you did it at the full level of the G20, you might be able to get some traction. Evasion at that level would be hard. But still I think it doesn't address the core problem which is really about financial institutions that are 'Too Big to Fail'. Financial transaction tax is more of a tax on regular people like you and me.[50][51]

Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill

Main article: Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill

In 2009, U.S. Representative Peter DeFazio of Oregon proposed a financial transaction tax in his "Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill". (This was proposed domestically for the United States only.)[52]

Would there be net job losses if a FTT tax was introduced?

Schwabish (2005) examined the potential effects of introducing a stock transaction(or "transfer") tax in a single city (New York) on employment not only in the securities industry, but also in the supporting industries. A financial transactions tax would lead to job losses also in non-financial sectors of the economy through the so called multiplier effect forwarding in a magnified form any taxes imposed on Wall Street employees through their reduced demand to their suppliers and supporting industries. The author estimated the ratios of financial- to non-financial job losses of between 10:1 to 10:4, that is "a 10 percent decrease in securities industry employment would depress employment in the retail, services, and restaurant sectors by more than 1 percent; in the business services sector by about 4 percent; and in total private jobs by about 1 percent."[53]

It is also possible to estimate the impact of a reduction in stock market volume caused by taxing stock transactions on the rise in the overall unemployment rate. For every 10 percent decline in stock market volume, elasticities estimated by Schwabish[53] implied that a stock transaction ("transfer") tax could cost New York City between 30,000 and 42,000 private-sector jobs, and if the stock market volume reductions reached levels observed by Umlauf (1993) in Sweden after a stock FTT was introduced there ("By 1990, more than 50% of all Swedish trading had moved to London")[26] then according to Schwabish (2005), following an introduction of a FTT tax, there would be 150,000-210,000 private-sector jobs losses in the New York alone.

In 2000, Round argued as follows:

When importers and exporters can’t be certain from one day to the next what their money is worth, economic planning—including job creation—goes out the window. Reduced exchange-rate volatility means that businesses would need to spend less money ‘hedging’ (buying currencies in anticipation of future price changes), thus freeing up capital for investment in new production [and the accompanying new jobs].[35]

The cost of currency hedges—and thus "certainty what importers and exporters' money is worth"—has nothing to do with volatility whatsoever, as this cost is exclusively determined by the interest rate differental between two currencies. Nevertheless, as Tobin said, "If ... [currency] is suddenly withdrawn, countries have to drastically increase interest rates for their currency to still be attractive."[3][4]

Is there an optimum tax rate?

Financial transaction tax rates of the magnitude of 0.1%-1% have been proposed by normative economists, without addressing the practicability of implementing a tax at these levels. In positive economics studies however, where due reference was paid to the prevailing market conditions, the resulting tax rates have been significantly lower.

For instance, Edwards (1993) concluded that if the transaction tax revenue from taxing the futures markets were to be maximized (see Laffer curve), with the tax rate not leading to a prohibitively large increase in the marginal cost of market participants, the rate would have to be set so low that "a tax on futures markets will not achieve any important social objective and will not generate much revenue."[54]

Political opinion

Opinions are divided between those who applaud that the Tobin tax could protect countries from spillovers of financial crises, and those who claim that the tax would also constrain the effectiveness of the global economic system, increase price volatility, widen bid-ask spreads for end users such as investors, savers and hedgers, and destroy liquidity.

Tobin tax proponents response to empirical evidence on volatility

Lack of direct supporting evidence for stabilizing (volatility-reducing) properties of Tobin-style transaction taxes in econometric research is acknowledged by some of the Tobin tax supporters:

Ten studies report a positive relationship between transaction taxes and short-term price volatility, five studies did not find any significant relationship. (Schulmeister et al, 2008, p. 18).[55]

These Tobin tax proponents have to therefore rely on indirect evidence in their favor, reinterpreting studies which do not deal directly with volatility, but instead with trading volume (with volume being generally reduced by transaction taxes, though it constitutes their tax base, see: negative feedback loop). This allows these Tobin tax proponents to state that "some studies show (implicitly) that higher transaction costs might dampen price volatility. This is so because these studies report that a reduction of trading activities is associated with lower price volatility." So if a study finds that reducing trading volume or trading frequency reduces volatility, these Tobin tax supporters combine it with the observation that Tobin-style taxes are volume-reducing, and thus should also indirectly reduce volatility ("this finding implies a negative relationship between [..] transaction tax [..] and volatility, because higher transaction costs will 'ceteris paribus' always dampen trading activities)." (Schulmeister et al., 2008, p. 18).[55]

There is yet another reason why some proponents of the Tobin tax maintain that it can reduce volatility, despite prevailing empirical evidence to the contrary. This is possible, because some Tobin tax supporters created a concept of a separate, custom-defined volatility. Rather than adopting one of the standard statistical definitions (e.g., conditional variance of returns, see Engle, 1982 [56]) leading economists favoring the Tobin tax prefer to define volatility as a "long-term overshooting of speculative prices" (see Tobin, 1978 [57] and Eichengreen, Tobin and Wyplosz, 1995 [58]). Evidence about this special type of volatility is missing and this is why some of the proponents, instead of conducting their own tests, prefer to blame financial econometric researchers for not addressing their special needs:

Unfortunately, all empirical studies on the relationship between transaction costs, trading volume and price volatility in general, and on the possible effects of an FTT on volatility in particular, deal with short-term statistical volatility only. Therefore, the results of these studies cannot help to answer the question whether or not an FTT will mitigate misalignments of asset prices over the medium and long run.—Schulmeister et al, 2008, p. 11[55]

Thus the beneficial impact of transaction taxes on the "Tobin volatility" can co-exist as a valid economic theory even without direct supporting evidence from the statistical volatility research, simply because of the special volatility definition, which allows all economists defending the Tobin tax to escape Popperian falsifiability.[citation needed]

Another shortcoming of all of the empirical volatility studies pointed out by some of the Tobin tax proponents is the lack of distinction between "basic" and "excessive" volatility, which "might have contributed to the contradictory and, hence, inconclusive results of these

studies" (Schulmeister et al., 2008, p. 11-12).[55] Unfortunately, no tests have been conducted so far, which would be able to operationalize "excessive" volatility assumed to exist by the Tobin tax theory (see Schulmeister et al., 2008, p. 11),[55] therefore the acceptance of the Tobin-style transactions tax as a fiscal or monetary policy instrument requires clear understanding that basic theoretical phenomena underlying this tax, such as "excessive" volatility, still remain untested.

Should speculators be encouraged, penalized or dissuaded?

The Tobin tax rests on the premise that speculators ought to be, as Tobin puts it, "dissuaded."[4][5][6][7] This premise itself is a matter of debate: See main debate at main article on "speculation"..

Matthew Sinclair, Research Director of TaxPayers' Alliance, argues that "The whole idea of a Tobin tax is based on the flawed view that trading – or speculation – is a bad thing. The truth is that it isn’t: it helps the process of price discovery, makes markets work better, enhances liquidity, ensures that resources are priced correctly and generally helps oil the cogs of the global economy."[29]

On the other side of the debate were the leaders of Germany who, in May 2008, planned to propose a worldwide ban on oil trading by speculators, blaming the 2008 oil price rises on manipulation by hedge funds. At that time India, with similar concerns, had already suspended futures trading of five commodities.[59]

On December 3, 2009, US Congressman Peter DeFazio stated, "The American taxpayers bailed out Wall Street during a crisis brought on by reckless speculation in the financial markets, ... This [ proposed financial transaction tax ] legislation will force Wall Street to do their part and put people displaced by that crisis back to work."[52]

On January 21, 2010, President Barack Obama endorsed the Volcker Rule which deals with proprietary trading of investment banks[60] and restricts banks from making certain speculative kinds of investments if they are not on behalf of their customers.[60] Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, President Obama's advisor, has argued that such speculative activity played a key role in the financial crisis of 2007–2010.

Volcker endorsed only the UK's tax on bank bonuses, calling it "interesting", but was wary about imposing levies on financial market transactions, because he is "instinctively opposed" to any tax on financial transactions.[61]

Questions of volatility

In February 2010, Tim Harford, writing in the Undercover Economist column of the Financial Times, commented directly on the claims of Keynes and Tobin that 'taxes on financial transactions would reduce financial volatility'.[62] Harford wrote:-

This is possible but far from obvious, when you realise that the tax might encourage bigger, more irregular financial transactions. An analogy: if I have to pay a charge whenever I use a cash machine, I make fewer, larger withdrawals and the amount of money in my wallet fluctuates more widely. Bear in mind, too, that the most bubble-prone asset market is for housing, which is bought in very lumpy, long-term chunks.

There isn’t much evidence as to whether transaction charges reduce volatility. What there is is mixed – but perhaps leaning against the Robin Hood tax. On the French stock market, coarser 'tick sizes' raise spreads and act like a tax: they increase volatility. Transaction taxes on Swedish stocks in the 1980s reduced prices and turnover but left volatility unchanged.

Comparing Currency Transaction Taxes (CTT) and Financial Transaction Taxes (FTT)