Carl Edward Sagan I06.docx

-

Upload

kenny-jeanfranco-casamayor-moreno -

Category

Documents

-

view

258 -

download

1

Transcript of Carl Edward Sagan I06.docx

Carl Edward Sagan (Nueva York, Estados Unidos, 9 de noviembre de 1934-Seattle, Estados

Unidos, 20 de diciembre de 1996) fue un astrónomo, astrofísico, cosmólogo, escritor y divulgador

científico estadounidense.

Sagan publicó numerosos artículos científicos y comunicaciones1 y fue autor, coautor o editor de

más de una veintena de libros. Defensor del pensamiento escéptico científico y del método

científico, fue también pionero de la exobiología, promotor de la búsqueda de inteligencia

extraterrestre a través del Proyecto SETI e impulsó el envío de mensajes a bordo de sondas

espaciales, destinados a informar a posibles civilizaciones extraterrestres acerca de la cultura

humana. Mediante sus observaciones de la atmósfera de Venus, fue de los primeros científicos

en estudiar el efecto invernadero a escala planetaria.

En la Universidad Cornell, Carl Sagan fue el primer científico en ocupar la Cátedra David Duncan

de Astronomía y Ciencias del Espacio, creada en 1976, y fue director del Laboratorio de Estudios

Planetarios.

Carl Sagan ha sido muy popular por sus libros de divulgación científica —en 1978, ganó

el Premio Pulitzer de Literatura General de No Ficción por su libro Los Dragones del Edén—, por

la galardonada serie documental de TV Cosmos: Un viaje personal, producida en 1980, de la

que fue narrador y coautor, y por el libro Cosmos que fue publicado como complemento de la

serie, además de por la novela Contacto, en la que se basa la película homónima de 1997. A lo

largo de su vida, Sagan recibió numerosos premios y condecoraciones por su labor como

comunicador de la ciencia y la cultura. Está considerado como uno de los divulgadores de la

ciencia más carismáticos e influyentes, gracias a su capacidad de transmitir las ideas científicas

y los aspectos culturales al público no especializado con sencillez no exenta de rigor, lo que ha

dado origen a multitud de vocaciones científicas entre el público general.

Infancia y adolescenciaCarl Sagan nació en Brooklyn, Nueva York,2 en una familia de judíos ucranianos. Su padre, Sam

Sagan, era un obrero de la industria textil nacido en Kamenets-Podolsk, Ucrania,3 y su madre,

Rachel Molly Gruber, era ama de casa. Carl recibió su nombre en honor de la madre biológica de

Rachel, Chaiya Clara; en palabras de Sagan, la madre que ella nunca conoció. Sagan se graduó

en la Rahway High School de Rahway, Nueva Jersey, en 1951.4

Carl tenía una hermana, Carol; la familia vivía en un modesto apartamento cerca del Océano

Atlántico, en Bensonhurst, un barrio de Brooklyn. Según Sagan, eran judíos reformistas, el más

liberal de los tres principales grupos judíos. Tanto Sagan como su hermana coinciden en que su

padre no era especialmente religioso, pero que su madre indudablemente creía en Dios, y

participaba activamente en el templo...; y sólo servía carne kosher.4 Durante el auge de la Gran

Depresión, su padre tuvo que aceptar un empleo como acomodador de cine.

Según el biógrafo Keay Davidson, la guerra interior de Sagan era resultado de la estrecha

relación que mantenía con sus padres, quienes eran opuestos en muchos sentidos. Sagan

remontaba sus posteriores impulsos analíticos a su madre, una mujer que conoció la pobreza

extrema siendo niña, y que había crecido casi sin hogar en la ciudad de Nueva York durante la I

Guerra Mundial y la década de 1920.4 Tenía las ambiciones propias de una mujer joven, pero

bloqueadas por las restricciones sociales, por su pobreza, por ser mujer y esposa, y por ser de

etnia judía. Davidson señala que ella, por tanto, adoraba a su único hijo, Carl. Él haría realidad

sus sueños no cumplidos.4

Sin embargo, su capacidad para sorprenderse venía de su padre, que era un tranquilo y

bondadoso fugitivo del Zar. En su tiempo libre, regalaba manzanas a los pobres o ayudaba a

suavizar las tensiones entre patronos y obreros en la tumultuosa industria textil de Nueva

York.4 Aunque intimidado por la brillantez de Carl, por sus infantiles parloteos sobre estrellas y

dinosaurios, se tomó con calma la curiosidad de su hijo, como parte de su educación.4 Años más

tarde, como escritor y científico, Sagan recurriría a sus recuerdos de la infancia para ilustrar

ideas científicas, como hizo en su libro El mundo y sus demonios.4 Sagan describe así la

influencia de sus padres en su pensamiento posterior:

Mis padres no eran científicos. No sabían casi nada de ciencia. Pero al iniciarme simultáneamente al escepticismo y a hacerme preguntas, me enseñaron los dos modos de pensamiento que conviven precariamente y que son fundamentales para el método científico.5

La Exposición Universal de 1939

Sagan recordaba que vivió una de sus mejores experiencias cuando, con cuatro o cinco años de

edad, sus padres lo llevaron a la Exposición Universal de Nueva York de 1939. La muestra se

convirtió en un punto de inflexión en su vida. Tiempo después recordaba el mapa móvil de

la América del Mañana:

Se veían hermosas autopistas y cruces a nivel y pequeños coches General Motors que llevaban gente a los rascacielos, edificios con bonitos pináculos, arbotantes... ¡y todo tenía una pinta genial!4

En otras exhibiciones, recordaba cómo una lámpara que iluminaba una célula fotoeléctrica

creaba un sonido crujiente, y cómo el sonido de un diapasón se convertía en una onda en

un osciloscopio. También fue testigo de la tecnología del futuro que reemplazaría a la radio:

la televisión. Sagan escribió:

Sencillamente, el mundo contenía maravillas que yo nunca había imaginado. ¿Cómo podía convertirse un tono en una imagen, y una luz convertirse en ruido?4

También pudo ver uno de los eventos más publicitados de la Exposición: el entierro de

una cápsula del tiempo en Flushing Meadows, que contenía recuerdos de la década de 1930

para ser recuperados por las generaciones venideras de un futuro milenio. La cápsula del tiempo

emocionó a Carl, escribe Davidson. De adulto, Sagan y sus colegas crearon cápsulas del tiempo

similares, pero para enviarlas a la galaxia: la Placa de la Pioneer y el Disco de Oro de las

Voyager, fueron producto de los recuerdos de Sagan sobre la Exposición Universal.4

Curiosidad por la naturaleza

Poco después de ingresar en la escuela elemental, Sagan comenzó a expresar una fuerte

curiosidad por la naturaleza. Sagan recordaba sus primeras visitas en solitario a la biblioteca

pública, a la edad de cinco años, cuando su madre le regaló un carné de lector. Quería saber

qué eran las estrellas, ya que ninguno de sus amigos ni sus padres sabían darle una respuesta

clara:

Fui al bibliotecario y pedí un libro sobre las estrellas... Y la respuesta fue sensacional. Resultó que el Sol era una estrella pero que estaba muy cerca. Las estrellas eran soles, pero tan lejanos que sólo parecían puntitos de luz... De repente, la escala del universo se abrió para mí. Fue una especie de experiencia religiosa. Había algo magnífico en ello, una grandiosidad, una escala que jamás me ha abandonado. Que nunca me abandonará.4

Por la época en que tenía seis o siete años, Sagan y un amigo fueron al Museo Americano de

Historia Natural de la ciudad de Nueva York. Allí estuvieron en el Planetario Hayden y pasearon

por las exhibiciones de objetos espaciales del museo, como los meteoritos, y las muestras

de dinosaurios y animales en entornos naturales. Sagan escribió sobre esas visitas:

Me quedaba paralizado ante las representaciones en dioramas realistas de los animales y de sus hábitats de todo el mundo. Pingüinos sobre el hielo apenas iluminado de la Antártida... una familia de gorilas, con el macho golpeándose el pecho... un oso grizzly en pie sobre sus patas traseras, de diez o doce pies de alto, y mirándome fijamente a los ojos.4

Los padres de Sagan ayudaron a alimentar el creciente interés de éste por la ciencia

comprándole juegos de química y material de lectura.6 Su interés por el espacio era, sin

embargo, su principal foco, especialmente después de leer las historias de ciencia-ficción de

escritores como Edgar Rice Burroughs, quienes estimulaban su imaginación acerca de cómo

sería la vida en otros planetas, como Marte. Según el biógrafo Ray Spangenburg, estos primeros

años en los que Sagan trataba de comprender los misterios de los planetas, se convirtieron en

una fuerza motora en su vida, una chispa continua para su intelecto, y una búsqueda que jamás

sería olvidada.5

Formación y carrera científicaCarl Sagan se matriculó en la Universidad de Chicago, donde participó en la Ryerson

Astronomical Society,7 graduándose en artes, en 1954, con honores especiales y generales; en

ciencias, en 1955, y obteniendo un máster en Física, en 1956, para luego doctorarse

en Astronomía y Astrofísica, en 1960.8 Durante su etapa de pregrado, Sagan trabajó en el

laboratorio del genetista Hermann Joseph Muller. De 1960 a 1962, Sagan disfrutó de una Beca

Miller para la Universidad de California, Berkeley. De 1962 a 1968, trabajó en el Smithsonian

Astrophysical Observatory en Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sagan impartió clases e investigó en la Universidad de Harvard hasta 1968, año en el que se

incorporó a la Universidad Cornell, en Ithaca, Nueva York. En 1971, fue nombrado profesor

titular y director del Laboratorio de Estudios Planetarios. De 1972 a 1981, Sagan fue Director

Asociado del Centro de Radiofísica e Investigación Espacial de Cornell. Desde 1976 hasta su

muerte, fue el primer titular de la Cátedra David Duncan de Astronomía y Ciencias del Espacio.

Sagan estuvo vinculado al programa espacial estadounidense desde los inicios de éste. Desde

la década de 1950, trabajó como asesor de la NASA, donde uno de sus cometidos fue dar las

instrucciones del Programa Apolo a los astronautas participantes antes de partir hacia la Luna.

Sagan participó en muchas de las misiones que enviaron naves espaciales robóticas a explorar

el Sistema Solar, preparando experimentos para varias expediciones. Concibió la idea de añadir

un mensaje universal y perdurable a las naves destinadas a abandonar el sistema solar que

pudiese ser potencialmente comprensible por cualquier inteligencia extraterrestre que lo

encontrase. Sagan preparó el primer mensaje físico enviado al espacio exterior:

una placa anodizada, unida a la sonda espacial Pioneer 10, lanzada en 1972. La Pioneer 11, que

llevaba otra copia de la placa, fue lanzada al año siguiente. Sagan continuó refinando sus

diseños; el mensaje más elaborado que ayudó a desarrollar y preparar fue el Disco de Oro de las

Voyager, que fue enviado con las sondas espaciales Voyager en 1977. Sagan se opuso

frecuentemente a la decisión de financiar el Transbordador Espacial y la Estación Espacial a

expensas de futuras misiones robóticas.9

Sagan impartió un curso de pensamiento crítico en la Universidad Cornell, hasta su muerte en

1996.

Logros científicosLas contribuciones de Sagan fueron vitales para el descubrimiento de las altas temperaturas

superficiales del planeta Venus. A comienzos de la década de 1960 nadie sabía a ciencia cierta

cuáles eran las condiciones básicas de la superficie de dicho planeta, y Sagan enumeró las

posibilidades en un informe que posteriormente fue divulgado en un libro de Time-

Life titulado Planetas. En su opinión, Venus era un planeta seco y muy caliente en oposición al

paraíso templado que otros imaginaban. Había investigado las emisiones de radio procedentes

de Venus y llegado a la conclusión de que la temperatura superficial de éste debía de ser de

unos 380 °C. Como científico visitante del Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro de la NASA,

participó en las primeras misiones delPrograma Mariner a Venus, trabajando en el diseño y

gestión del proyecto. En 1962, la sonda Mariner 2 confirmó sus conclusiones sobre las

condiciones superficiales del planeta.

Sagan fue de los primeros en plantear la hipótesis de que una de las lunas de Saturno, Titán,

podría albergar océanos de compuestos líquidos en su superficie, y que una de las lunas

de Júpiter, Europa, podría tener océanos de agua subterráneos. Esto haría que Europa fuese

potencialmente habitable por formas de vida.10 El océano subterráneo de agua de Europa fue

posteriormente confirmado de forma indirecta por la sonda espacial Galileo. El misterio de la

bruma rojiza de Titán también fue resuelto con la ayuda de Sagan, debiéndose a moléculas

orgánicas complejas en constante lluvia sobre la superficie de la luna saturniana.11

Sagan también contribuyó a la mejor comprensión de las atmósferas de Venus y Júpiter y de los

cambios estacionales de Marte. Determinó que la atmósfera de Venus es extremadamente

caliente y densa con presiones en gradual aumento hasta la superficie planetaria. También

percibió el calentamiento global como un peligro creciente de origen humano y lo comparó con la

evolución natural de Venus hacia un planeta caliente y no apto para la vida como consecuencia

de un efecto invernadero fuera de control. Sagan y su colega de Cornell, Edwin Ernest Salpeter,

especularon sobre la posibilidad de la existencia de vida en las nubes de Júpiter, dada la

composición de la densa atmósfera del planeta, rica en moléculas orgánicas. También estudió

las variaciones de color de la superficie de Marte y concluyó que no se trataba de cambios

estacionales o vegetales, como muchos creían, sino desplazamientos del polvo superficial

causados por tormentas de viento.

Sin embargo, Sagan es más conocido por sus investigaciones sobre la posibilidad de la vida

extraterrestre, incluyendo la demostración experimental de la producción

deaminoácidos mediante radiación y a partir de reacciones químicas básicas.12

En 1994, Sagan recibió la Medalla de Bienestar Público, la mayor condecoración de la Academia

Nacional de Ciencias de Estados Unidos por sus destacadas contribuciones a la aplicación de la

ciencia al bienestar público.13 Se dice que le fue denegado el ingreso en dicha Academia porque

su actividad en los medios le había hecho impopular ante otros científicos.14

Abanderado de la CienciaLa habilidad de Sagan para transmitir sus ideas permitió que muchas personas comprendiesen

mejor el cosmos, enfatizando simultáneamente el valor de la raza humana, y la relativa

insignificancia de la Tierra respecto del universo. En Londres, impartió la edición de 1977 de

las Royal Institution Christmas Lectures.15 Fue presentador, coautor y coproductor --junto a Ann

Druyan y Steven Soter-- de la popular serie de televisión de trece capítulos Cosmos: Un viaje

personal, producida por el PBS, y que seguía el formato de la también serie El ascenso del

hombre, presentada por Jacob Bronowski.

Sagan defendió la búsqueda de vida extraterrestre, instando a la comunidad científica a

utilizar radiotelescopios para buscar señales procedentes de formas de vida extraterrestres

potencialmente inteligentes. Sagan fue tan persuasivo que, en 1982, logró publicar en la

revista Science una petición de defensa del Proyecto SETI firmada por 70 científicos entre los

que se encontraban siete ganadores del Premio Nobel, lo que supuso un enorme espaldarazo a

la respetabilidad de un campo tan controvertido. Sagan también ayudó al Dr. Frank Drake a

preparar el mensaje de Arecibo, una emisión de radio dirigida al espacio desde el radiotelescopio

de Arecibo el 16 de noviembre de 1974, destinada a informar sobre la existencia de la Tierra a

posibles seres extraterrestres.

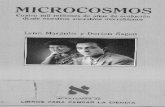

Los fundadores de la Sociedad Planetaria. Carl Sagan, sentado a la derecha.

De 1968 a 1979, Sagan fue editor de la Revista Icarus, publicación para profesionales sobre

investigación planetaria. Fue co-fundador de la Sociedad Planetaria, el mayor grupo del mundo

dedicado a la investigación espacial, con más de cien mil miembros en más de 149 países, y fue

miembro del Consejo de Administración del Instituto SETI. Sagan ejerció también de Presidente

de la División de Ciencia Planetaria (DPS) de la Sociedad Astronómica Americana, de

Presidente de la Sección de Planetología de la American Geophysical Union, y de Presidente de

la Sección de Astronomía de la Asociación Estadounidense para el Avance de la Ciencia.

En el clímax de la Guerra Fría, Sagan dedicó parte de sus esfuerzos a concienciar a la opinión

pública sobre los efectos de una guerra nuclear cuando un modelo matemático del clima sugirió

que un intercambio nuclear de proporciones suficientes podría desestabilizar el delicado

equilibrio de la vida en la Tierra. Fue uno de los cinco autores —el autor "S"— del

informe TTAPS, como fue conocido dicho artículo de investigación. Finalmente, fue coautor del

artículo científico que planteaba la hipótesis de un invierno nuclear global tras una guerra

nuclear.16 Carl Sagan relató su implicación en los debates políticos sobre el invierno nuclear y su

errónea predicción del enfriamiento global que causarían los incendios de los pozos petrolíferos

durante la Guerra del Golfo, en su libro, El mundo y sus demonios. También fue coautor del

libro A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race ("Un camino

que ningún humano pensó: el invierno nuclear y el fin de la carrera armamentista"), un análisis

exhaustivo del fenómeno del invierno nuclear.

La serie Cosmos abarcó un amplio espectro de materias científicas que incluían el origen de la

vida y una perspectiva de nuestro lugar en el universo. Fue estrenada por el Public Broadcasting

Service en 1980, ganando un Premio Emmy y un Premio Peabody. Ha sido emitida en más de

60 países y vista por más de 600 millones de personas, convirtiéndose en el programa

del PBS más visto de la historia.17 Además, la revista Time publicó un artículo de portada sobre

Sagan poco después del estreno, refiriéndose a él como el creador, autor principal y

presentador-narrador de la nueva serie de la televisión pública Cosmos, toma el control de su

nave de la fantasía.18

Sagan también escribió libros de divulgación científica que reflejan y desarrollan algunos de los

temas tratados en Cosmos, entre los que destacan Los dragones del Edén: Especulaciones

sobre la evolución de la inteligencia humana, que ganó un Premio Pulitzer y se convirtió en el

libro de ciencia en inglés más vendido de todos los tiempos;19 y El cerebro de Broca: Reflexiones

sobre el romance de la ciencia. Sagan también escribió, en 1985, la exitosa novela de ciencia-

ficción Contacto, basada en un proyecto de guion que ideó con su esposa en 1979, pero no

viviría para ver la adaptación cinematográfica de la misma, estrenada en 1997, protagonizada

por la actriz Jodie Foster, y que ganaría el Premio Hugo de 1998 a la "Mejor Presentación

Dramática".20

Un punto azul pálido: La Tierra no es más que un píxel brillante fotografiado desde laVoyager 1, a 6.000

millones de kilómetros de distancia (más allá de Plutón). Sagan convenció a la NASA para que generase

esta imagen.

Sagan escribió un libro continuación de Cosmos, llamado Un punto azul pálido: Una visión del

futuro humano en el espacio, que fue seleccionado como libro destacado de 1995 por The New

York Times. En enero de 1995, Sagan apareció en el programa de Charlie Rose, en

el PBS.21 También escribió una introducción al exitoso libro de Stephen Hawking, Breve historia

del tiempo. También fue conocido por su labor como divulgador de la Ciencia, por sus esfuerzos

para incrementar la comprensión científica del público en general, y por su posición en favor

del escepticismo científico y contra las pseudociencias, como su refutación de la abducción de

Betty y Barney Hill. Para señalar el décimo aniversario de la muerte de Sagan, David Morrison,

uno de sus antiguos alumnos, recordó las inmensas contribuciones de Sagan a la investigación

planetaria, a la comprensión pública de la ciencia, y al movimiento escéptico en la

revista Skeptical Inquirer.22

En enero de 1991, Sagan planteó la hipótesis de que una cantidad suficiente de humo

procedente de los incendios petroleros de Kuwait de ese año podría alcanzar una altura tal que

llegase a desmantelar la actividad agrícola en el sur de Asia ... Posteriormente reconoció, en El

mundo y sus demonios, que dicha predicción no resultó ser correcta: estaba oscuro como boca

de lobo a mediodía y las temperaturas cayeron entre 4 y 6 °C en el Golfo Pérsico, pero no fue

mucho el humo que alcanzó altitudes estratosféricas y Asia se salvó.23 En 2007, un estudio

aplicó modelos computacionales modernos a los incendios petroleros de Kuwait, resultando que

columnas individuales de humo no son capaces de elevar éste hasta la estratosfera, pero que el

humo procedente de fuegos que abarquen una gran superficie, como algunos incendios

forestales o los incendios de ciudades enteras producto de un ataque nuclear, sí que elevarían

cantidades significativas de humo a niveles estratosféricos.24 2526

En sus últimos años, Sagan abogó por la creación de una búsqueda organizada de objetos

cercanos a la Tierra que pudieran impactar contra ésta.27 Mientras otros expertos sugerían la

creación de grandes bombas nucleares que pudieran usarse para alterar la órbita de

un NEO susceptible de impacto terrestre, Sagan propuso el Dilema de la Desviación: al crear la

capacidad de alejar un asteroide de la Tierra, también se crea la capacidad de desviarlo hacia

ésta, dotando potencialmente a un poder maléfico con una auténtica bomba del fin del

mundo.28 29

Miles de millones

A partir de Cosmos y de sus frecuentes apariciones en el programa The Tonight Show Starring

Johnny Carson, comenzó a relacionarse a Sagan con la muletilla miles de millones y miles de

millones —en inglés estadounidense, billions and billions—. Sagan afirmaba que él nunca utilizó

esa frase en la serie.30 Lo más parecido que llegó a expresar está en el libro Cosmos, donde

habla de "miles y miles de millones":31

Una galaxia se compone de gas y de polvo y de estrellas, de miles y miles de millones de estrellas.

Sin embargo, su frecuente uso de la palabra billions, enfatizando la pronunciación de la "b" (de

forma intencionada para no recurrir a alternativas más farragosas, como decir billions with a "b",

para que el espectador distinguiese claramente dicha palabra de millions --millones--),30 le

convirtieron en el blanco favorito de humoristas como Johnny Carson,32 Gary Kroeger, Mike

Myers, Bronson Pinchot, Penn Jillette, Harry Shearer, y otros. Frank Zappa satirizó la expresión

en su canción Be In My Video, junto con el término "luz atómica" --atomic light--. Sagan se tomó

todo esto de buen humor hasta tal punto que su último libro se tituló Miles de millones,

iniciándolo con un análisis burlesco de la famosa expresión, señalando que el propio Carson era

un aficionado a la astronomía y que sus números a menudo incluían elementos de ciencia real.30

Sus habituales descripciones de enormes cantidades a escala cósmica inculcaron en la

percepción popular la maravilla de la inmensidad del espacio y el tiempo como, por ejemplo, su

frase El número total de estrellas en el Universo es mayor que el de todos los granos de arena

de todas las playas del planeta Tierra. Como homenaje humorístico, se ha definido

un sagan como una unidad de medida equivalente, al menos, a cuatro mil millones, puesto que

el número más pequeño que puede ser descrito como miles de millones y miles de millones es

dos mil millones más dos mil millones.33 34

Activismo socialSagan creía que la ecuación de Drake, a falta de estimaciones más razonables, sugiere la

formación de un gran número de civilizaciones extraterrestres, pero la falta de evidencia de la

existencia de las mismas, resaltada por la paradoja de Fermi, indicaría la tendencia de las

civilizaciones tecnológicas hacia la autodestrucción. Esto dio pie a su interés en identificar y dar

a conocer las diversas maneras en que la humanidad podría destruirse a si misma, con la

esperanza de poder evitar dicha catástrofe y, finalmente, posibilitar que los seres humanos se

conviertan en una especie capaz de viajar por el espacio. La profunda preocupación de Sagan

acerca de una potencial destrucción de la civilización humana en un holocausto nuclear quedó

plasmada en una memorable secuencia en el último episodio de la serie Cosmos,

titulado ¿Quién habla en nombre de la Tierra?. Sagan acababa de dimitir de su puesto en el

Consejo Científico Asesor de las Fuerzas Aéreas Estadounidenses y de rechazar

voluntariamente su autorización de acceso a asuntos de alto secreto en protesta por la Guerra

de Vietnam.35 Tras su matrimonio con la que sería su tercera esposa, la escritora Ann Druyan, en

junio de 1981, Sagan incrementó su actividad política, concretamente en su oposición a la

carrera armamentística nuclear, durante la presidencia de Ronald Reagan.

En marzo de 1983, Reagan dio a conocer la llamada Iniciativa de Defensa Estratégica, un

proyecto en el que se invirtieron miles de millones de dólares para desarrollar un completo

sistema de defensa contra ataques con misiles nucleares, que fue popularmente conocido

como Programa Guerra de las Galaxias. Sagan se opuso al proyecto, argumentando que era

técnicamente imposible desarrollar un sistema semejante con el nivel de perfección requerido, y

que sería mucho más caro elaborarlo que para un enemigo el eludirlo mediante señuelos u otros

medios, y que su construcción desestabilizaría seriamente la balanza nuclear entre los Estados

Unidos y la Unión Soviética, tornando imposible cualquier progreso hacia el desarme nuclear.

Cuando el líder soviético Mikhail Gorbachov declaró una moratoria unilateral sobre las pruebas

de armamento nuclear, que comenzaría el 6 de agosto de 1985, en el 40 aniversario de

los bombardeos atómicos sobre Hiroshima y Nagasaki, el gobierno de Reagan desestimó la

dramática iniciativa tachándola de propaganda, y rechazó seguir el ejemplo soviético. En

respuesta, activistas anti-nucleares y pacifistas estadounidenses llevaron a cabo una serie de

protestas en el emplazamiento de pruebas de Nevada, que se iniciarían el domingo de Pascua

de 1986 y continuarían hasta 1987. Cientos de personas fueron arrestadas, incluyendo a Sagan,

quien fue detenido en dos ocasiones al tratar de saltar un cordón de seguridad.5

Vida privada, ideas y creenciasCiencia y religión

El escritor Isaac Asimov describió a Sagan como una de las dos únicas personas que había

conocido cuyo intelecto superaba al suyo, siendo la otra el informático y experto en inteligencia

artificial, Marvin Minsky.36

Sagan escribía a menudo sobre la religión y sobre la relación entre ésta y la ciencia, expresando

su escepticismo sobre la convencional conceptualización de Dios como ser sapiente:

Alguna gente piensa en Dios imaginándose un hombre anciano, de grandes dimensiones, con una larga barba blanca, sentado en un trono en algún lugar ahí arriba en el cielo, llevando afanosamente la cuenta de la muerte de cada gorrión. Otros —por ejemplo, Baruch Spinoza y Albert Einstein— consideraban que Dios es básicamente la suma total de las leyes físicas que describen al universo. No sé de ningún indicio de peso en favor de algún patriarca capaz de controlar el destino humano desde algún lugar privilegiado oculto en el cielo, pero sería estúpido negar la existencia de las leyes físicas.37

En otra descripción de su punto de vista sobre Dios, Sagan afirma rotundamente:

La idea de que Dios es un hombre blanco de grandes dimensiones y de larga barba blanca, sentado en el cielo y que lleva la cuenta de la muerte de cada gorrión es ridícula. Pero si por Dios uno entiende el conjunto de leyes físicas que gobiernan el universo, entonces está claro que dicho Dios existe. Este Dios es emocionalmente insatisfactorio... no tiene mucho sentido rezarle a la ley de la gravedad.38

En el libro El mundo y sus demonios (1995), Sagan ejemplifica la falacia del argumento

especial con ejemplos exclusivamente religiosos:

un argumento especial, a menudo para salvar una proposición en un problema retórico profundo (p. ej.: ¿Cómo puede un Dios compasivo condenar al tormento a las generaciones futuras porque, contra sus órdenes, una mujer indujo a un hombre a comerse una manzana? Argumento especial: no entiendes la sutil doctrina del libre albedrío. O: ¿Cómo puede haber un Padre, Hijo y Espíritu Santo igualmente divinos en la misma persona? Argumento especial: no entiendes el misterio divino de la Santísima Trinidad. O: ¿Cómo podía permitir Dios que los seguidores del judaísmo, cristianismo e islam —obligados cada uno a su modo a medidas heroicas de amabilidad afectuosa y compasión— perpetraran tanta crueldad durante tanto tiempo? Argumento especial: otra vez no entiendes el libre albedrío. Y, en todo caso, los caminos de Dios son misteriosos);39

En 1996, en respuesta a una pregunta acerca de sus creencias religiosas, Sagan contestó: Soy

agnóstico.40 El punto de vista de Sagan sobre la religión ha sido interpretado como una forma

de panteísmo comparable a la creencia de Einstein en el Dios de Spinoza.41 Sagan sostenía que

la idea de un creador del universo era difícil de probar o refutar, y que el único descubrimiento

científico que podría desafiarla sería el de un universo infinitamente viejo.42 Según su última

esposa, Ann Druyan, Sagan no era creyente:

Cuando mi esposo murió, debido a que era tan famoso y conocido por ser un no creyente, muchas personas se me acercaban —aún sucede a veces— a preguntarme si Carl cambió al final y se convirtió en un creyente en la otra vida. También me preguntan con frecuencia si creo que le volveré a ver. Carl se enfrentó a su muerte con infatigable valor y jamás buscó refugio en ilusiones. Lo trágico fue saber que jamás nos volveríamos a ver. No espero volver a reunirme con Carl.43

En 2006, Ann Druyan editó las Conferencias Gifford sobre Teología Natural, impartidas por

Sagan en Glasgow, en el año 1985, incluyéndolas en un libro llamado La diversidad de la

ciencia: una visión personal de la búsqueda de Dios, en el que el astrónomo expone su punto de

vista sobre la divinidad en el mundo natural.

Librepensador y escéptico

Sagan también está considerado como librepensador y escéptico; una de sus frases más

famosas, de la serie Cosmos, es: Afirmaciones extraordinarias requieren evidencias

extraordinarias.44 Dicha frase está basada en otra casi idéntica de su colega fundador del Comité

para la Investigación Escéptica, Marcello Truzzi: Una afirmación extraordinaria requiere una

prueba extraordinaria.45 Esta idea tuvo su origen en Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827),

matemático y astrónomo francés, quien dijo que el peso de la evidencia de una afirmación

extraordinaria debe ser proporcional a su rareza.

A lo largo de su vida, los libros de Sagan fueron desarrollados sobre su visión del mundo,

naturalista y escéptica. En El mundo y sus demonios, Sagan presentó herramientas para probar

argumentos y detectar falacias y fraudes, abogando esencialmente por el uso extensivo del

pensamiento crítico y del método científico. La recopilación Miles de millones, publicada en 1997

tras la muerte de Sagan, contiene ensayos, como su visión sobre el aborto, y el relato de su

viuda, Ann Druyan, sobre su muerte como escéptico, agnóstico y librepensador.

Sagan advirtió contra la tendencia humana hacia el antropocentrismo. Fue asesor de los

Alumnos de Cornell por el Trato Ético hacia los Animales. Hacia el final del capítuloBlues para un

planeta rojo, del libro Cosmos, Sagan escribió: «Si hay vida en Marte creo que no deberíamos

hacer nada con el planeta. Marte pertenecería entonces a los marcianos, aunque los marcianos

fuesen sólo microbios».[cita requerida]

El fenómeno ovni

Sagan mostró interés en los informes sobre el fenómeno ovni al menos desde el 3 de agosto de

1952, cuando escribió una carta al Secretario de Estado estadounidense Dean

Acheson preguntándole cómo responderían los EE. UU. si los platillos volantes resultaran ser de

origen extraterrestre.46 Posteriormente, en 1964, mantuvo varias conversaciones sobre el asunto

con Jacques Vallée.47 A pesar de su escepticismo acerca de la obtención de cualquier respuesta

extraordinaria a la cuestión ovni, Sagan creía que los científicos debían estudiar el fenómeno,

aunque sólo fuese por el gran interés que el asunto despertaba en el público.

Stuart Appelle comenta que Sagan «escribió frecuentemente sobre lo que él percibía como

falacias lógicas y empíricas acerca de los ovnis y las experiencias de abducción. Sagan

rechazaba la explicación extraterrestre del fenómeno pero tenía la sensación de que examinar

los informes ovni tendría beneficios empíricos y pedagógicos, y que el asunto sería, por tanto,

una materia de estudio legítima».48

En 1966, Sagan fue miembro del Comité Ad Hoc para la Revisión del Proyecto Libro Azul,

promovido por la Fuerza Aérea de los EE. UU. para investigar el fenómeno ovni. El comité

concluyó que el Libro Azul dejaba que desear como estudio científico, y recomendó la realización

de un proyecto de corte universitario para someter el fenómeno a un escrutinio más científico. El

resultado fue la formación del Comité Condon (1966-1968), liderado por el físico Edward

Condon, y que, en su informe final, dictaminó formalmente que los ovnis, con independencia de

su origen y significado, no se comportaban de manera consistente para representar una

amenaza a la seguridad nacional.

Ron Westrum escribe: «El punto culminante del tratamiento que Sagan dio a la cuestión ovni fue

el simposio de la AAAS de 1969. Los participantes expusieron un amplio abanico de opiniones

formadas en el tema, incluyendo no sólo a partidarios como James McDonald y J. Allen

Hynek sino también a escépticos como los astrónomos William Hartmann y Donald Menzel. La

lista de ponentes estaba equilibrada, y es mérito de Sagan el que dicho evento tuviera lugar a

pesar de la presión ejercida por Edward Condon».47 Junto al físico Thornton Page, Sagan editó

las conferencias y debates presentados en el simposio; éstos se publicaron en 1972 bajo el

título UFOs: A Scientific Debate. En algunos de los numerosos libros de Sagan se examina la

cuestión ovni (al igual que en uno de los episodios de Cosmos) y se afirma la existencia de un

trasfondo religioso al fenómeno.

En 1980, Sagan volvió a revelar su punto de vista sobre los viajes interestelares en la

serie Cosmos. En una de sus últimas obras escritas, Sagan expuso que la probabilidad de que

naves espaciales extraterrestres visitasen la Tierra era muy pequeña. Sin embargo, Sagan creía

que era plausible que la preocupación causada por la Guerra Fríacontribuyese a que los

gobiernos desorientasen a los ciudadanos acerca de los ovni, y que «algunos de los análisis e

informes sobre ovnis, y quizá archivos voluminosos, hayan sido declarados inaccesibles al

público que paga las impuestos... Es hora de que esos archivos sean desclasificados y puestos

a disposición de todos». También previno acerca de sacar conclusiones sobre datos eliminados

sobre los ovnis e insistió en que no existían claras evidencias de que posibles alienígenas

hubieran visitado la Tierra ni en el pasado ni en el presente.49

2001: Una odisea del espacio

Sagan ejerció brevemente de asesor en la película 2001: Una odisea del espacio, dirigida

por Stanley Kubrick.4 Sagan propuso que la película sugiriese, sin mostrar, la existencia de una

superinteligencia extraterrestre.50

Enfermedad y fallecimiento

Dos años después de diagnosticársele una mielodisplasia, y después de someterse a

tres trasplantes de médula óseaprocedente de su hermana, el Dr. Carl Sagan falleció

de neumonía a los 62 años de edad en el Centro de Investigación del Cáncer Fred

Hutchinson de Seattle, Washington, el 20 de diciembre de 1996.62 63 Fue enterrado en el

Cementerio Lakeview,Ithaca, Nueva York.64

Reconocimientos y premiosSagan fue el autor de la introducción al libro divulgativo Historia del Tiempo, del físico

británico Stephen Hawking, en su primera edición en lengua inglesa (1988). Dicha introducción

fue sustituida en posteriores ediciones debido a que Sagan era el propietario de los derechos de

copia.

La película Contacto, de 1997, basada en la novela homónima de Sagan y acabada tras la

muerte de éste, finaliza con la dedicatoria Para Carl.

También en 1997 se inauguró en Ithaca, Nueva York, el Sagan Planet Walk, una recreación del

sistema solar a escala de a pie, con una extensión de 1,2 km, desde el centro de la zona

peatonal (llamada The Commons) hasta el Sciencenter, un museo de la ciencia participativo, del

que Sagan fue miembro fundador de la junta de asesores.65

El lugar de aterrizaje de la nave no tripulada Mars Pathfinder fue rebautizado como Carl Sagan

Memorial Station el 5 de julio de 1997. Además, el asteroide 2709 Sagan lleva dicho nombre en

honor del científico.

Nick Sagan, hijo de Carl, es autor de varios episodios de la franquicia Star Trek. El episodio de la

serie Star Trek: Enterprise titulado Terra Prime, muestra una breve imagen de los restos del

robot explorador Sojourner, que formó parte de la misión Mars Pathfinder, situados junto a un

monumento conmemorativo en la Carl Sagan Memorial Station, sobre la superficie marciana. El

monumento muestra una frase de Sagan: Sea cual sea la razón por la que esteis en Marte,

estoy encantado de que esteis aquí, y yo desearía estar con vosotros. Steve Squyres, alumno de

Sagan, dirigió el equipo que depositó con éxito el Spirit Rover y el Opportunity Rover sobre Marte

en 2004.

El 9 de noviembre de 2001, en el 67º aniversario del nacimiento de Sagan, el Ames Research

Center de la NASA dedicó al científico el emplazamiento del Centro Carl Sagan para el Estudio

de la Vida en el Cosmos. El responsable de la NASA, Daniel Goldin dijo: Carl fue un visionario

increíble, y ahora su legado podrá ser preservado y ampliado por un laboratorio de investigación

y formación del siglo XXI dedicado a mejorar nuestra comprensión de la vida en el universo y a

enarbolar la causa de la exploración espacial por siempre jamás. Ann Druyan estuvo en la

apertura de puertas del Centro, el 22 de octubre de 2006.

Existen, al menos, tres premios que llevan el nombre de Sagan en honor a éste:

El Premio Carl Sagan para la Comprensión Pública de la Ciencia otorgado por el Consejo de

Presidentes de la Sociedad Científica (CSSP). Sagan fue el primer galardonado en 1993.66

El Premio Conmemorativo Carl Sagan, otorgado en conjunto desde 1997 por la Sociedad

Astronáutica Americana y la Sociedad Planetaria.

La Medalla Carl Sagan a la Excelencia en la Divulgación de la Ciencia Planetaria, otorgada

desde 1998 por la División de Ciencias Planetarias (DPS) de la Sociedad Astronómica

Americana, a los científicos planetarios en activo que hayan realizado algún trabajo

destacado de divulgación. Sagan fue uno de los miembros del comité organizador original de

la DPS.

Desde 2009, por inicitiava del Center for Inquiry, varias organizaciones en pro del humanismo

secular y la investigación científica promueven la celebración del Día de Carl Sagan el 9 de

noviembre de cada año.

Carl Sagan ha recibido diversos premios, condecoraciones y honores entre los que destacan:

Beca Miller de Investigación (1960-1962) del Instituto Miller.

Premio del Programa Apolo concedido por la NASA.

Premio Klumpke-Roberts (1974) de la Sociedad Astronómica del Pacífico.

Premio John W. Campbell Memorial Especial no ficción (1974) por La conexión cósmica.71

Medalla de la NASA al Servicio Público Distinguido (1977).

Medalla de la NASA al Logro Científico Excepcional .

Premio Pulitzer (1978) en la categoría de obra no ficcional general al ensayo Los dragones

del Edén.

Premio Lowell Thomas del Club de Exploradores en el 75º Aniversario.

Premio Peabody (1980) a la serie Cosmos.

Premio Emmy (1981), en la categoría de Logro Destacado Individual, por la serie Cosmos:

un viaje personal.

Premio Primetime Emmy (1981), en la categoría de Serie Documental Destacada, por la

serie Cosmos: un viaje personal.

Premio Anual a la Excelencia Televisiva (1981) concedido por la Universidad Estatal de

Ohio a la serie Cosmos: un viaje personal.

Premio Hugo por el "Mejor Relato No Ficcional" (1981) al libro Cosmos.72

Humanista del Año (1981) de la Asociación Humanista Americana.

Premio John F. Kennedy de Astronáutica (1982) de la Sociedad Astronáutica Americana.73

Premio Joseph Priestley — "Por destacadas contribuciones al bienestar de la humanidad".

Medalla Konstantín Tsiolkovski otorgada por la Federación Soviética de Cosmonautas.

Premio Locus (1986) a la novela Contacto.

Premio Elogio de la Razón (1987) del Comité para la Investigación Científica de las

Afirmaciones de lo Paranormal

Premio Masursky de la Sociedad Astronómica Americana.

Medalla Oersted (1990) de la Asociación Americana de Profesores de Física.

Premio Galbert de Astronáutica.

Premio Helen Caldicott al Liderazgo – otorgado por la Acción Femenina por el Desarme

Nuclear.[cita requerida]

Medalla de Bienestar Público (1994) de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias 74

Premio Isaac Asimov (1994) del Comité para la Investigación Científica de las Afirmaciones

de lo Paranormal.

Premio San Francisco Chronicle (1998) por Contact.[cita requerida]

Carl Edward Sagan (/ˈseɪɡən/; November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) was an

American astronomer, cosmologist, astrophysicist,astrobiologist, author, science popularizer,

and science communicator in astronomy and other natural sciences. His contributions were

central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of Venus. However, he is best known for

his contributions to the scientific research of extraterrestrial life, including experimental

demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation. Sagan

assembled the first physical messages that were sent into space: the Pioneer plaque and

the Voyager Golden Record, universal messages that could potentially be understood by any

extraterrestrial intelligence that might find them.

He published more than 600 scientific papers and articles and was author, co-author or editor of

more than 20 books. Sagan wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of

Eden, Broca's Brain and Pale Blue Dot, and narrated and co-wrote the award-winning 1980

television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. The most widely-watched series in the history of

American public television, Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people across 60

different countries.[2] The book Cosmos was published to accompany the series. He also wrote

the science fiction novel Contact, the basis for a 1997 film of the same name.

Sagan always advocated scientific skeptical inquiry and the scientific method,

pioneered exobiology and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI). He spent

most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the

Laboratory for Planetary Studies. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honors,

including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the National Academy of

Sciences Public Welfare Medal, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for his book The

Dragons of Eden, and, regarding Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, two Emmy Awards, the Peabody

Award and the Hugo Award. He married three times and had five children. After suffering

from myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62 on December 20, 1996.

Early life[edit]

Carl Sagan was born in Brooklyn, New York.[3] His father, Samuel Sagan, was an immigrant

garment worker from Kamianets-Podilskyi, then Russian Empire,[4][5] in today's Ukraine. His

mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York. Carl was named in honor of

Rachel's biological mother, Chaiya Clara, in Sagan's words, "the mother she never knew."[6]

He had a sister, Carol, and the family lived in a modest apartment near the Atlantic Ocean,

in Bensonhurst, a Brooklyn neighborhood. According to Sagan, they were Reform Jews, the most

liberal of North American Judaism's four main groups. Both Sagan and his sister agreed that their

father was not especially religious, but that their mother "definitely believed in God, and was

active in the temple ... and served only kosher meat."[6]:12 During the depths of the Depression, his

father worked as a theater usher.

According to biographer Keay Davidson, Sagan's "inner war" was a result of his close relationship

with both of his parents, who were in many ways "opposites." Sagan traced his later analytical

urges to his mother, a woman who had been extremely poor as a child in New York City

during World War I and the 1920s.[6]:2 As a young woman she had held her own intellectual

ambitions, but they were frustrated by social restrictions: her poverty, her status as a woman and

a wife, and her Jewish ethnicity. Davidson notes that she therefore "worshipped her only son,

Carl. He would fulfill her unfulfilled dreams."[6]:2

However, he claimed that his sense of wonder came from his father. In his free time he gave

apples to the poor or helped soothe labor-management tensions within New York's garment

industry.[6]:2 Although he was awed by Carl's intellectual abilities, he took his son's inquisitiveness

in stride and saw it as part of his growing up.[6]:2 In his later years as a writer and scientist, Sagan

would often draw on his childhood memories to illustrate scientific points, as he did in his

book, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.[6]:9 Sagan describes his parents' influence on his later

thinking:

My parents were not scientists. They knew almost nothing about science. But in

introducing me simultaneously to skepticism and to wonder, they taught me the two

uneasily cohabiting modes of thought that are central to the scientific method.[7]

Inquisitiveness about nature[edit]

Soon after entering elementary school he began to express a strong inquisitiveness about nature.

Sagan recalled taking his first trips to the public library alone, at the age of five, when his mother

got him a library card. He wanted to learn what stars were, since none of his friends or their

parents could give him a clear answer:

I went to the librarian and asked for a book about stars ... And the answer was stunning. It was

that the Sun was a star but really close. The stars were suns, but so far away they were just little

points of light ... The scale of the universe suddenly opened up to me. It was a kind of religious

experience. There was a magnificence to it, a grandeur, a scale which has never left me. Never

ever left me.[6]:18

At about age six or seven, he and a close friend took trips to the American Museum of

Natural History in New York City. While there, they went to the Hayden Planetarium and

walked around the museum's exhibits of space objects, such as meteorites, and displays of

dinosaurs and animals in natural settings. Sagan writes about those visits:

I was transfixed by the dioramas—lifelike representations of animals and their habitats all over

the world. Penguins on the dimly lit Antarctic ice; ...a family of gorillas, the male beating his

chest, ...an American grizzly bear standing on his hind legs, ten or twelve feet tall, and staring me

right in the eye.[6]:18

His parents helped nurture his growing interest in science by buying him chemistry sets

and reading materials. His interest in space, however, was his primary focus, especially

after reading science fiction stories by writers such as H. G. Wells and Edgar Rice

Burroughs, which stirred his imagination about life on other planets such as Mars.

According to biographer Ray Spangenburg, these early years as Sagan tried to

understand the mysteries of the planets became a "driving force in his life, a continual

spark to his intellect, and a quest that would never be forgotten."[7]

In 1947 he discovered Astounding Science Fiction magazine, which introduced him to

more hard science fiction speculations than those in Burroughs's novels. That same year

inaugurated the "flying saucer" mass hysteria with the young Carl suspecting the "discs"

might be alien spaceships.[8]

High school years[edit]

Sagan had lived in Bensonhurst where he went to David A. Boody Junior High School.

He had his bar mitzvah in Bensonhurst when he turned 13.[6]:23 The following year, 1948,

his family moved to the nearby town of Rahway, New Jersey for his father's work, where

Sagan then entered Rahway High School. He graduated in 1951.[6]:23 Rahway was an

older industrial town, and the Sagans were among its few Jewish families. Today the

town is best known as the site of a state prison. [6] :23

Sagan was a straight-A student but was bored due to unchallenging classes and

uninspiring teachers.[6]:23 His teachers realized this and tried to convince his parents to

send him to a private school, the administrator telling them, "This kid ought to go to a

school for gifted children, he has something really remarkable."[6]:24 This they couldn't do,

partly because of the cost.

Sagan was made president of the school's chemistry club, and at home he set up his

own laboratory. He taught himself about molecules by making cardboard cutouts to help

him visualize how molecules were formed: "I found that about as interesting as doing

[chemical] experiments," he said.[6]:24 Sagan remained mostly interested in astronomy as a

hobby, and in his junior year made it a career goal after he learned that astronomers

were paid for doing what he always enjoyed: "That was a splendid day—when I began to

suspect that if I tried hard I could do astronomy full-time, not just part-time."[6]:25

Education and scientific career[edit]

He attended the University of Chicago, where he participated in the Ryerson

Astronomical Society,[9] received a B.A. degree in self-proclaimed "nothing" with general

and special honors in 1954, a B.S. degree in physics in 1955, and an M.S. degree

in physics in 1956, before earning a Ph.D. degree in 1960 with the dissertation "Physical

Studies of Planets" submitted to the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics.[10][11][12]

[13] The title of Sagan's thesis reflects his shared interests with Gerard Kuiper,

his dissertation director, who throughout the 1950s had been president of

the International Astronomical Union's commission on "Physical Studies of Planets and

Satellites".[14]

During his time as an honors program undergraduate, Sagan worked in the laboratory of

the geneticist H. J. Muller and wrote a thesis on the origins of life with physical chemist H.

C. Urey. He used the summer months of his graduate studies to work with planetary

scientist Gerard Kuiper, physicist George Gamow, and chemist Melvin Calvin. From 1960

to 1962 Sagan was a Miller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.[15] From 1962

to 1968, he worked at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge,

Massachusetts. At the same time, he worked with geneticist Joshua Lederberg.

Sagan lectured and did research at Harvard University until 1968, when he moved to

Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, after being denied tenure at Harvard. It has been

suggested that Sagan was denied tenure in part because of his publicized scientific

advocacy, which some scientists perceived as being self-promotion;[16] Harold Urey wrote

a letter to the tenure committee recommending against tenure for Sagan.[8] He became

a full professor at Cornell in 1971, and directed the Laboratory for Planetary

Studies there. From 1972 to 1981, Sagan was associate director of the Center for

Radiophysics and Space Research (CRSR) at Cornell.

Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program from its inception. From the 1950s

onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA, where one of his duties included briefing

theApollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of

the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments

on many of the expeditions. He conceived the idea of adding an unalterable and

universal message on spacecraft destined to leave the Solar System that could

potentially be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find it. Sagan

assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-anodized plaque,

attached to the space probePioneer 10 , launched in 1972. Pioneer 11 , also carrying

another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his

designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was

the Voyager Golden Record that was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977.

Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and the International

Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions.[17]

Sagan taught a course on critical thinking at Cornell University until he died in 1996 from

pneumonia, a few months after finding that he was in remission of myelodysplastic

syndrome.

Scientific achievements[edit]

Former student David Morrison describes Sagan as "an 'idea person' and a master of

intuitive physical arguments and 'back of the envelope' calculations,"[16] and Gerard

Kuiper said that "Some persons work best in specializing on a major program in the

laboratory; others are best in liaison between sciences. Dr. Sagan belongs in the latter

group."[16]

Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of

the planet Venus.[citation needed] In the early 1960s no one knew for certain the basic conditions

of that planet's surface, and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report later depicted for

popularization in a Time–Life book, Planets. His own view was that Venus was dry and

very hot as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated

radio emissions from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of

500 °C (900 °F). As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he

contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and

management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his conclusions on the surface

conditions of Venus in 1962.

Sagan was among[clarification needed] the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might

possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter's moon Europamight

possess subsurface oceans of water. This would make Europa potentially habitable.[18] Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the

spacecraftGalileo. The mystery of Titan's reddish haze was also solved with Sagan's

help. The reddish haze was revealed to be due to complex organic molecules constantly

raining down onto Titan's surface.[19]

He further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter as well

as seasonal changes on Mars. He also perceived global warming as a growing, man-

made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile

planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect.[20] Sagan and his Cornell

colleagueEdwin Ernest Salpeter speculated about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the

planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the

observed color variations on Mars' surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or

vegetational changes as most believed[clarification needed] but shifts in surface dust caused

by windstorms.

Sagan is best known, however, for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life,

including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic

chemicals by radiation.[21][22]

He is also the 1994 recipient of the Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of

the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of

science to the public welfare".[23] He was denied membership in the Academy, reportedly

because his media activities made him unpopular with many other scientists.[24][25][26]

Scientific and critical thinking advocacy[edit]

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better

—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the

relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the Universe. He delivered the 1977

series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in London.[27] He hosted and, with Ann

Druyan, co-wrote and co-produced the highly popular thirteen-part Public Broadcasting

Service (PBS) television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage.[28]

Cosmos covered a wide range of scientific subjects including the origin of life and a

perspective of our place in the Universe. The series was first broadcast by PBS in 1980,

winning an Emmy [29] and a Peabody Award. It has been broadcast in more than 60

countries and seen by over 500 million people,[2][30] making it the most widely watched

PBS program in history.[31] In addition, Time magazine ran a cover story about Sagan

soon after the show broadcast, referring to him as "creator, chief writer and host-narrator

of the new public television series Cosmos, [and] takes the controls of his fantasy

spaceship".[32] However, Sagan was criticized for putting too much attention into the

series, with several of his classes at Cornell being cancelled and complaints from his

colleagues.[16]

Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific

community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential

intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms. Sagan was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able

to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science and signed by 70

scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This was a tremendous increase in the

respectability of this controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo

message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on

November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research

journal Icarus for twelve years. He co-founded The Planetary Society, the largest space-

interest group in the world, with over 100,000 members in more than 149 countries, and

was a member of theSETI Institute Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the

Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the

Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the

Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in public awareness efforts for the

effects ofnuclear war when a 1982 mathematical climate model, titled "Twilight at

Noon" suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could trigger a nuclear twilight and

upset the delicate balance of life on Earth by cooling the surface. In 1983 he was one of

five authors—the "S"—in the follow-up "TTAPS" report, as the research paper came to

be known, which contained the term "nuclear winter" for the first time, a term coined by

his colleague Richard P. Turco.[33][34] In 1984 he co-authored the book The Cold and the

Dark: The World after Nuclear War and in 1990 he co-authored the book A Path Where

No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race, which explains the

nuclear winter hypothesis and with that advocates nuclear disarmament.

Sagan also wrote books to popularize science, such as Cosmos, which reflected and

expanded upon some of the themes of A Personal Voyage and became the best-selling

science book ever published in English;[35] The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the

Evolution of Human Intelligence, which won a Pulitzer Prize; and Broca's Brain:

Reflections on the Romance of Science. Sagan also wrote the best-selling science fiction

novel Contact in 1985, based on a film treatment he wrote with his wife in 1979, but he

did not live to see the book's 1997 motion picture adaptation, which starred Jodie

Foster and won the 1998 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

from Pale Blue Dot (1994)

"On it, everyone you ever heard of...The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident

religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every

creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every hopeful

child, every mother and father, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt

politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived

there on a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam. . . .

Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they

could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot."

Carl Sagan, Cornell lecture in 1994[36]

He wrote a sequel to Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space,

which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by The New York Times. He appeared on

PBS' Charlie Rose program in January 1995.[17] Sagan also wrote the introduction

for Stephen Hawking's bestseller, A Brief History of Time. Sagan was also known for his

popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the

general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism and

againstpseudoscience, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction. To

mark the tenth anniversary of Sagan's death, David Morrison, a former student of

Sagan's, recalled "Sagan's immense contributions to planetary research, the public

understanding of science, and the skeptical movement" in Skeptical Inquirer.[16]

Following Saddam Hussein's threats to light Kuwait's oil wells on fire in response to any

physical challenge to Iraqi control of the oil assets, Sagan and his "TTAPS" colleagues

warned in January 1991 in the Baltimore Sun and Wilmington Morning Starnewspapers

that if the fires were left to burn over a period of several months, enough smoke from the

600 or so 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires "might get so high as to disrupt agriculture in much of

South Asia ..." and that this possibility should "affect the war plans";[37][38] these claims

were also the subject of a televised debate between Sagan and physicist Fred Singer on

22 January, aired on the ABC News program Nightline.[39][40]

In the televised debate, Sagan argued that the effects of the smoke would be similar to

the effects of a nuclear winter, with Singer arguing to the contrary. After the debate, the

fires burnt for many months before extinguishing efforts were complete, the results of the

smoke did not produce continental-sized cooling. Sagan later conceded in The Demon-

Haunted World that the prediction did not turn out to be correct: "it waspitch black at noon

and temperatures dropped 4°–6 °C over the Persian Gulf, but not much smoke reached

stratospheric altitudes and Asia was spared".[41]

In his later years Sagan advocated the creation of an organized search for

asteroids/near-Earth objects (NEO) that might impact the Earth, and to postpone

developing the technology to defend against them.[42] He argued that the nuclear

detonation, along with the other methods of deflection proposed as a means to alter the

orbit of an asteroid, created a Deflection Dilemma: if the ability to deflect an asteroid

away from the Earth exists, then one would also have the ability to deflect a close

approaching asteroid towards Earth, creating an immensely destructive weapon.[43][44] In a

1994 paper, he co-authored, he ridiculed a 3-day long "Near-Earth Object Interception

Workshop" held byLANL in 1993 that did not, "even in passing" state that such

interception and deflection technologies could have these "ancillary dangers".[45]

Sagan however was hopeful that the natural impact threat and the intrinsically double

edged essence of the methods to prevent these threats, would serve as a "new and

potent motivation to maturing international relations".[46][47] Later acknowledging that, with

sufficient international oversight, in the future a "work our way up" approach to fielding

nuclear explosive deflection methods could be fielded, and when sufficient knowledge

was gained, to use them to aid in mining asteroids.[44] His interest in the use of nuclear

detonations in space grew out of his work in 1958 for the Armour Research

Foundation's Project A119, concerning the possibility of detonating a nuclear device on

the Lunar surface.[48]

Sagan was a critic of Plato. Sagan said of Plato: "Science and mathematics were to be

removed from the hands of the merchants and the artisans. This tendency found its most

effective advocate in a follower of Pythagoras named Plato" and "He (Plato) believed that

ideas were far more real than the natural world. He advised the astronomers not to waste

their time observing the stars and planets. It was better, he believed, just to think about

them. Plato expressed hostility to observation and experiment. He taught contempt for

the real world and disdain for the practical application of scientific knowledge. Plato's

followers succeeded in extinguishing the light of science and experiment that had been

kindled by Democritus and the other Ionians."[49]

Popularizing science[edit]

Speaking about his activities in popularizing science, Sagan said that there were at least

two reasons for scientists to explain what science is about. Naked self-interest was one

because much of the funding for science came from the public, and the public had a right

to know how their money was being spent. If scientists increased public excitement about

science, there was a good chance of having more public supporters. The other reason

was the excitement of communicating one's own excitement about science to others.[50]

"Billions and billions"[edit]

From Cosmos and his frequent appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny

Carson, Sagan became associated with thecatchphrase "billions and billions". Sagan

said that he never actually used the phrase in the Cosmos series.[51] The closest that he

ever came was in the book Cosmos, where he talked of "billions upon billions":[52]

A galaxy is composed of gas and dust and stars—billions upon billions of stars.[20]

(Richard Feynman, a precursor to Sagan, is observed to use the phrase "billions and

billions" many times in his "red books".) However, Sagan's frequent use of the

word billions, and distinctive delivery emphasizing the "b" (which he did intentionally, in

place of more cumbersome alternatives such as "billions with a 'b'", in order to distinguish

the word from "millions"),[51] made him a favorite target of comic performers,

including Johnny Carson,[53] Gary Kroeger, Mike Myers, Bronson Pinchot, Penn

Jillette, Harry Shearer, and others.Frank Zappa satirized the line in the song "Be in My

Video", noting as well "atomic light". Sagan took this all in good humor, and his final book

was entitled Billions and Billions, which opened with a tongue-in-cheek discussion of this

catchphrase, observing that Carson was an amateur astronomer and that Carson's comic

caricature often included real science.[51]

He is also known for expressing wonderment at the vastness of space and time, as in his

phrase "The total number of stars in the Universe is larger than all the grains of sand on

all the beaches of the planet Earth."

As a humorous tribute to Sagan and his association with the catchphrase "billions and

billions", a sagan has been defined as a unit of measurement equivalent to a very large

number of anything.[54][55][56]

Social concerns[edit]

Sagan believed that the Drake equation, on substitution of reasonable estimates,

suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack

of evidence of such civilizations highlighted by the Fermi

paradox suggests technological civilizations tend to self-destruct. This stimulated his

interest in identifying and publicizing ways that humanity could destroy itself, with the

hope of avoiding such a cataclysm and eventually becoming a spacefaring species.

Sagan's deep concern regarding the potential destruction of human civilization in

a nuclear holocaust was conveyed in a memorable cinematic sequence in the final

episode of Cosmos, called "Who Speaks for Earth?" Sagan had already

resigned[date missing] from the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board's UFO investigating Condon

Committee and voluntarily surrendered his top secret clearance in protest over

the Vietnam War.[57] Following his marriage to his third wife (novelist Ann Druyan) in June

1981, Sagan became more politically active—particularly in opposing escalation of

the nuclear arms race under President Ronald Reagan.

In March 1983, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative—a multibillion-dollar

project to develop a comprehensive defenseagainst attack by nuclear missiles, which

was quickly dubbed the "Star Wars" program. Sagan spoke out against the project,

arguing that it was technically impossible to develop a system with the level of perfection

required, and far more expensive to build such a system than it would be for an enemy to

defeat it through decoys and other means—and that its construction would seriously

destabilize the "nuclear balance" between the United States and the Soviet Union,

making further progress toward nuclear disarmament impossible.[citation needed]

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev declared a unilateral moratorium on the testing of

nuclear weapons, which would begin on August 6, 1985—the 40th anniversary of

the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—the Reagan administration dismissed the dramatic

move as nothing more than propaganda, and refused to follow suit. In response, US anti-

nuclear and peace activists staged a series of protest actions at the Nevada Test Site,

beginning on Easter Sunday in 1986 and continuing through 1987. Hundreds of people in

the "Nevada Desert Experience" group were arrested, including Sagan, who was

arrested on two separate occasions as he climbed over a chain-link fence at the test site

during the underground Operation Charioteer and United States's Musketeer nuclear test

series of detonations.[58]

Sagan was also a vocal advocate of the controversial notion of testosterone poisoning,

arguing in 1992 that human males could become gripped by an "usually severe [case of]

testosterone poisoning" and this could compel them to become genocidal.[59] In his review

ofMoondance magazine writer Daniela Gioseffi's 1990 book Women on War, he argues

that females are the only half of humanity "untainted by testosterone poisoning".[60] One

chapter of his 1993 book, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is dedicated to testosterone

and its alleged poisonous effects.[61]

Personal life and beliefs[edit]

Sagan was married three times. In 1957, he married biologist Lynn Margulis, mother

of Dorion Sagan and Jeremy Sagan. After Sagan and Margulis divorced, he married

artistLinda Salzman in 1968, mother of Nick Sagan. During these marriages, Sagan

focused heavily on his career, a factor which may have contributed to Sagan's first

divorce.[16] In 1981, Sagan married author Ann Druyan, mother of Alexandra Rachel

(Sasha) Sagan and Samuel Democritus Sagan. Sagan and Druyan remained married

until his death in 1996.

"I have just finished The Cosmic Connection and loved every word of it. You are my idea of a good writer because you have an unmannered style, and when I read what you write, I hear you talking. One thing about the book made me nervous. It was entirely too obvious that you are smarter than I am. I hate that."

Isaac Asimov, in letter to Sagan, 1973[62]

Isaac Asimov described Sagan as one of only two people he ever met whose intellect

surpassed his own. The other, he claimed, was the computer scientist and artificial

intelligence expert Marvin Minsky.[63]

Sagan wrote frequently about religion and the relationship between religion and science,

expressing his skepticism about the conventional conceptualization of God as a sapient

being. For example:

Some people think God is an outsized, light-skinned male with a long white beard, sitting

on a throne somewhere up there in the sky, busily tallying the fall of every sparrow.

Others—for example Baruch Spinozaand Albert Einstein—considered God to be

essentially the sum total of the physical laws which describe the universe. I do not know

of any compelling evidence for anthropomorphic patriarchs controlling human destiny

from some hidden celestial vantage point, but it would be madness to deny the existence

of physical laws.[64]

In another description of his view on the concept of God, Sagan emphatically writes:

The idea that God is an oversized white male with a flowing beard who sits in the sky and

tallies the fall of every sparrow is ludicrous. But if by God one means the set of physical

laws that govern the universe, then clearly there is such a God. This God is emotionally

unsatisfying ... it does not make much sense to pray to the law of gravity.[65]

On atheism, Sagan commented in 1981:

An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who has

compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such compelling

evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places and to ultimate

causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the universe than we do now to

be sure that no such God exists. To be certain of the existence of God and to be certain

of the nonexistence of God seem to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so

riddled with doubt and uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed.[66]

Sagan also commented on Christianity, stating "My long-time view about Christianity is

that it represents an amalgam of two seemingly immiscible parts, the religion of Jesus

and the religion of Paul. Thomas Jefferson attempted to excise the Pauline parts of the

New Testament. There wasn't much left when he was done, but it was an inspiring

document."[67]

Regarding the relationship between spirituality and science, Sagan stated: "Science is

not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we

recognize our place in an immensity of light-years and in the passage of ages, when we

grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of

elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual."[68]

An environmental appeal, "Preserving and Cherishing the Earth", signed by Sagan with

other noted scientists in January 1990, stated that "The historical record makes clear that

religious teaching, example, and leadership are powerfully able to influence personal

conduct and commitment... Thus, there is a vital role for religion and science."[69]

In reply to a question in 1996 about his religious beliefs, Sagan answered, "I'm

agnostic."[70] Sagan maintained that the idea of a creator God of the Universe was difficult

to prove or disprove and that the only conceivable scientific discovery that could

challenge it would be an infinitely old universe.[71] Sagan's views on religion have been