A Model of Oligopoly

Transcript of A Model of Oligopoly

Jul io de 2021

A Model of Oligopoly

Hernán Vallejo

Documento CEDE

# 38

Serie Documentos Cede, 2021-38 ISSN 1657-7191

Edición electrónica. Julio de 2021

© 2021, Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Economía,

CEDE. Calle 19A No. 1 – 37 Este, Bloque W. Bogotá, D. C.,

Colombia Teléfonos: 3394949- 3394999, extensiones 2400,

2049, 2467

http://economia.uniandes.edu.co

Impreso en Colombia – Printed in Colombia

La serie de Documentos de Trabajo CEDE se circula con propó-

sitos de discusión y divulgación. Los artículos no han sido

evaluados por pares ni sujetos a ningún tipo de evaluación

formal por parte del equipo de trabajo del CEDE. El contenido

de la presente publicación se encuentra protegido por las

normas internacionales y nacionales vigentes sobre propiedad

intelectual, por tanto su utilización, reproducción, comunica-

ción pública, transformación, distribución, alquiler, préstamo

público e importación, total o parcial, en todo o en parte, en

formato impreso, digital o en cualquier formato conocido o por

conocer, se encuentran prohibidos, y sólo serán lícitos en la

medida en que se cuente con la autorización previa y expresa

por escrito del autor o titular. Las limitaciones y excepciones

al Derecho de Autor, sólo serán aplicables en la medida en que

se den dentro de los denominados Usos Honrados (Fair use),

estén previa y expresamente establecidas, no causen un grave

e injustificado perjuicio a los intereses legítimos del autor o

titular, y no atenten contra la normal explotación de la obra.

Universidad de los Andes | Vigilada Mineducación Reconoci-

miento como Universidad: Decreto 1297 del 30 de mayo de

1964. Reconocimiento personería jurídica: Resolución 28 del

23 de febrero de 1949 Minjusticia.

Documento CEDE

Los documentos CEDE son producto de

las investigaciones realizadas por al menos

un profesor de planta de la Facultad de

Economía o sus investigadores formalmente

asociados.

A Model of Oligopoly

Hernan Vallejo

Universidad de los Andes

Facultad de Economıa

Bogota D.C., Colombia

July 27, 2021

Abstract

This article builds a simple model of oligopoly and uses it to make a detailed charac-

terization of the equilibrium prices; quantities; mark-ups; price elasticities of market

demand; price elasticities of residual demand; and welfare, all in terms of the param-

eters of the model. This is done under five different conjectures -Collusion, Threat,

Cournot, Stackelberg and Bertrand-. The results of the model are used do compar-

ative statics.

JEL Classification: C70, C71, D43, L13.

Keywords: Oligopoly, Collusion, Threat, Cournot, Stackelberg, Bertrand, mark-up

Un modelo de oligopolio

Hernan Vallejo

Universidad de los Andes

Facultad de Economıa

Bogota D.C., Colombia

Este artıculo construye un modelo simple de oligopolio y lo utiliza para hacer una caracter-

izacion detallada del equilibrio en terminos de precios; cantidades; mark-ups; elasticidades

precio de la demanda del mercado; elasticidades precio de la demanda residual y el bienes-

tar, en funcion de los parametros del modelo. Esto se hace bajo cinco conjeturas diferentes

-Colusion, Amenaza, Cournot, Stackelberg y Bertrand-. Los resultados del modelo se uti-

lizan para hacer ejercicios de estatica comparativa.

Clasificaciones JEL: C70, C71, D43, L13.

Palabras claves: Oligopolio, Colusion, Amenaza, Cournot, Stackelberg, Bertrand y

mark-up.

1 Introduction

This article presents a simple model of oligopoly. To do so, the same market demand

and the same cost structure per firm are used, in order to characterize the market equilib-

rium in terms of the parameters of the model, under five different conjectures -Collusion,

Threat, Cournot, Stackelberg and Bertrand-. The results are used to do comparative

statics.

2 Previous literature

The term oligopoly has been traced back by Chamberlain (1957), to St. Thomas

More´s “Utopia” (1518), where he used it to refer to the “the sale by the few”. Schlesinger

(1914) used the German word “oligopolische”, without a theory and without influence.

Oligopoly as a term was later used and massified by Chamberlein (1933) in his book “The

Theory of Monopolistic Competition”.

Cournot (1838) presented the first formal model of oligopoly, which remains at the

core of this theory and is regarded by authors such as Shapiro (1989), as one of the most

important -if not the most important- contribution to the topic.

Bertrand (1883) criticized Cournot and proposed that if players could choose between

quantity competition and price competition, price competition would prevail. With con-

stant returns to scale, the Bertrand price is equal to the competitive price, which is equal

to the marginal cost. Edgeworth (1897) critisized Cournot as well, pointing out that its

results had been shown to be wrong, regardless of the cost structures.

Shapiro (1989) made a thorough review of oligopoly theory, for static and dynamic

games. It has long been acknowledged that oligopolies have an equilibrium that can change

depending on the assumptions made and on the way firms interact among themselves. The

way firms interact among themselves, may also change across time.

Levin (1988) analyzed Collusion, Cournot and Stackelberg, and concluded that at

equilibrium, Collusion has greater prices than Cournot, and Cournot greater prices than

Stackelberg.

This article builds a simple model of oligopoly, that reflects some of the basic results

1

obtained in the literature, expressing them in terms of the parameters of the model.

Vallejo (2021) makes a similar approach for oligopsony in a factor (labor) market, which

has mirror opposite features to this article, in order to highlight explicitly that mirror

symmetry between oligopoly and oligopsony.

3 A Model of the Oligopoly

The model constructed in this article aims to characterize in a detailed way the

oligopoly equilibrium in the markets of goods and services, under the conjectures of Col-

lusion, Threat, Cournot, Stackelbeg, and Bertrand.

3.1 General Assumptions

In order to achieve the objectives of this article, the following assumptions are made.

There are many consumers of a good or service, which are price takers. The market

demand curve is linear, or is linearized around the relevant equilibrium, as:

p = a− bQ

Where p is the unit price and Q are the total quantities produced and sold in the

market, and a and b are positive parameters (a > 0 and b > 0).

Consider two identical firms A and B, that produce a homogeneous product. Firms

have identical total cost functions (TC), with a non-negative and constant marginal cost

d ≥ 0, and no fixed costs. Fixed costs are zero, or are sunk, in order to focus on the role

of conjectural variations, and not on the role of economies of scale.

Thus, the total cost function of any firm, as a function of a firm’s output q, can be

written as:

TC = dq

The marginal cost of any firm is thus constant, and non-negative, as pointed out before:

MgCi = d

Just as in monopoly or monopolistic competition, there is no supply curve in oligopoly,

2

since firms maximize profits and to do so, they sell at the highest possible price, which is

given by the demand curve. This implies that all combinations of prices and quantities

are on the demand curve, and thus, it is impossible to find a combination of prices and

quantities sold, that is independent of such demand curve.

Given the market demand, the market price is a function of the quantities produced

and sold by firms A and B:

p = a− b(qA + qB)

The market existence condition implies that the demand intercept on the vertical axis

is greater than the marginal cost (a > d). If this condition does not hold, the market

collapses.

3.2 Perfect Competition

Perfect competition is not an oligopoly equilibrium in its own right, since there is

no scope for strategic interactions in this market structure. However, its equilibrium is

relevant as a benchmark for the welfare impacts of the different conjectures considered

here, under oligopoly.

In perfect competition, the profit maximization condition is that price equals marginal

cost, so the equilibrium prices, total quantities and the profits of any firm Πi, can be

written as:

p = d

a− bQ = d

Q =a− db

Π = Πi = 0

Since price equals marginal cost, there is no mark-up (MU) in perfect competition.

Measuring such mark-up with the Lerner Index:

MU =p−MgC

p=d− dd

= 0

3

At the equilibrium price, the price elasticity of the market demand (ε) is:

ε = −∂Q∂p

p

Q

ε =1

b

da−db

ε =d

a− d> 0

Since the residual demand is defined as the demand faced by the firm, which may

differ from the market demand, and since the price is given to the firm under Perfect

Competition, the price elasticity of the residual demand (εi), tends to infinity:

εi →∞

Firms have no surplus and no profits, so social welfare (W ) is equal to consumer surplus

(CS):

W = CS =1

2(a− d)

a− db

W = CS =(a− d)2

2b

3.3 Collusion

Collusion (or cartel) is the only cooperative conjecture considered in this article. It

occurs when firms cooperate to maximize total profits. As such, they replicate monopoly.

The total profits of the cartel (Π) can be written as:

Π = [a− bQ]Q− dQ

The first order condition for profit maximization is:

∂Π

∂Q= a− b2Q− d = 0

4

Q =a− d

2b> 0

Given that the marginal cost is constant, there is no apriori mechanism to allocate

output between firms. However, in a symmetric equilibrium:

qA = qB =a− d

4b> 0

Substituting Q in the demand equation:

p =a+ d

2> 0

The mark-up under Collusion, measured with the Lerner Index, can be expressed as:

MU =

[a+d2− d]

a+d2

MU =

[2(a+ d− 2d)

2(a+ d)

]MU =

a− da+ d

> 0

The price elasticity of the market demand at equilibrium is:

ε =1

b

a+d2

a−d2b

ε =a+ d

a− d> 0

The price elasticity of the residual demand at the symmetric equilibrium is:

εi =1

2b

a+d2

a−d4b

εi =a+ d

a− d> 0

The profits of each firm are:

5

ΠA = ΠB =

[[a+ d

2

]− d]a− d

4b

ΠA = ΠB =(a− d)2

8b> 0

The total profits Π are:

Π = ΠA + ΠB =(a− d)2

4b> 0

The social welfare loss (WL) with the Collusion outcome, with respect to the welfare

under the perfectly competitive equilibrium, is:

WL =1

2

[(a+ d)

2− d] [

(a− d)

b− (a− d)

2b

]

WL =(a− d)2

8b

3.4 Threat

Threat is a conjecture where there is an established firm A that acts as a monopolist,

and another firm B considers entering the market. A decreases the price or expands

production to discourage the entry of B, and once B desists from entering the market,

A moves back to being a monopolist. Thus, the Threat equilibrium is the Monopoly

equilibrium, which is the Collusion equilibrium, but all the production is done by firm A,

and all the profits are for firm A. Thus, the Threat equilibrium can be characterized in

terms of the parameters of the model, as follows:

Q = qA =a− d

2b> 0

p =a+ d

2> 0

MU =a− da+ d

> 0

6

ε = εi =a+ d

a− d> 0

Π = ΠA =(a− d)2

4b> 0

WL =(a− d)2

8b

3.5 Cournot

Under the Cournot conjecture, firms chose the level of production that maximizes their

profits, given the production of the other firm. Output decisions affect market prices.

Given the Cournot conjecture, the profits of firm A can be written as:

ΠA = [a− b(qA + qB)]qA − dqA

The first order condition for profit maximization is:

∂ΠA

∂qA= a− bqB − 2bqA − d = 0

The reaction function (optimal strategy) for firm A is:

qA =a− d− bqB

2b

By symmetry it can be verified that the reaction function for firm B is:

qB =a− d− bqA

2b

The profit maximizing output of firm A, in terms of the parameters of the model, can

be found replacing the reaction function of B into the reaction function of A:

qA =a− d− b

[a−d−bqA

2b

]2b

7

2bqA = a− d−[a− d− bqA

2

]

4bqA = 2a− 2d− a+ d+ bqA

3bqA = a− d

qA =a− d

3b> 0

By symmetry, it can be verified that:

qB =a− d

3b> 0

Total output in the market is:

Q =2(a− d)

3b> 0

The market price under Cournot is:

p = a− b2(a− d)

3b

p =a+ 2d

3> 0

The mark-up estimated as before, is:

MU =

[[a+2d3

]− d

a+2d3

]

MU =a− da+ 2d

> 0

The price elasticity of the market demand at equilibrium, is calculated as:

8

ε =1

b

a+2d3

2(a−d)3b

ε =a+ 2d

2(a− d)> 0

The price elasticity of residual demand for each firm at equilibrium, is calculated as:

εi =1

2b

a+2d3

(a−d)3b

εi =a+ 2d

2(a− d)> 0

The profits of each firm and the total profits, are:

ΠA = ΠB =

[(a+ 2d)

3− d]

(a− d)

3b

Πi =

[(a− d)

3

](a− d)

3b

Πi =(a− d)2

9b> 0

Π =2(a− d)2

9b> 0

The welfare loss with the Cournot outcome, with respect to the welfare under the

perfectly competitive equilibrium is:

WL =1

2

[(a+ 2d)

3− d] [

(a− d)

b− 2(a− d)

3b

]

WL =(a− d)2

18b

3.6 Stackelberg

Under the Stackelberg conjecture, firms do not cooperate but rather, compete, with

one firm acting as a leader in the output produced and sold in the market, and the other

firm acting as a follower. Assume firm B is the leader and firm A is the follower, and

9

thus, firm A takes the output of firm B as given. Production decisions of A and B affect

the output market prices.

The reaction function for firm A is the same as in Cournot:

qA =a− d− bqB

2b

Firm B knows it is the market leader, and it is aware that the output decisions of A,

depend on its own output decision. In fact, B knows the reaction function of A. Thus,

profit maximization for firm B can be expressed as:

ΠB = [a− b(qA + qB)]qB − dqB

ΠB =

[a− b

(a− d− bqB

2b+ qB

)]qB − dqB

ΠB =

[aqB + dqB − bq2B

2

]− dqB

The first order condition for profit maximization is:

∂ΠB

∂qB=

[a+ d− 2bqB

2

]− d = 0

qB =

[(a− d)

2b

]Replacing the optimal output of the leading firm B, in the reaction function of firm A:

qA =

[(a− d)

4b

]Total output in the market under Stackelberg is:

Q =

[3(a− d)

4b

]Replacing in the demand curve, the price is:

p =

[(a+ 3d)

4

]

10

And the mark-up is:

MU =

[a+3d4− d]

a+3d4

MU =a− da+ 3d

> 0

The price elasticity of the market demand is:

ε =1

b

a+3d4

3(a−d)4b

ε =a+ 3d

3(a− d)> 0

The price elasticity of the residual demand of the leading firm, that has two thirds of

the market output, is:

εi =2

3b

a+3d4

(a−d)2b

εi =a+ 3d

3(a− d)> 0

The price elasticity of the residual demand of the following firm, that has one third of

the market output, is:

εi =1

3b

a+3d4

(a−d)4b

εi =a+ 3d

3(a− d)> 0

The profits for A, B and the total profits, are:

ΠA =

[[a+ 3d

4

]− d]

(a− d)

4b

ΠA =(a− d)

4

(a− d)

4b

ΠA =(a− d)2

16b

ΠB =(a− d)

4

(a− d)

2b

11

ΠB =(a− d)2

8b

Π =(a− d)2

16b+

(a− d)2

8b

Π =3(a− d)2

16b> 0

The welfare loss with the Stackelberg outcome, with respect to the welfare under the

perfectly competitive equilibrium is:

WL =1

2

[(a+ 3d)

4− d] [

(a− d)

b− 3(a− d)

4b

]

WL =(a− d)2

32b

3.7 Bertrand

In Bertrand, firms compete in prices, meaning that they set their prices to maximize

their profits, taking the price of their competitor as given. Starting with any price, for

example the Cournot price, which as shown before has a mark-up over the marginal cost,

one firm will have the incentive to decrease the price and capture the whole market. But

the other firm will do the same, and capture all the market. At equilibrium, one or both

firms will set the price equal to the marginal cost of production, and sell all the quantities

demanded in the market.

Thus, under the setting of this article, the Bertrand equilibrium replicates the perfect

competition equilibrium, since the equilibrium price equals the marginal cost of produc-

tion.

Profit maximization in Bertrand can be expressed as:

p = d

a− bQ = d

Q =a− db

12

Since the marginal cost is assumed constant in this model, there is no a priori mech-

anism to allocate production between firms. However, in a symmetric equilibrium:

qA = qB =a− d

2b

ΠA = ΠB = 0

MU = 0

At the equilibrium price, the price elasticity of the market demand is:

ε =d

a− d> 0

The price elasticity of the residual demand is:

εi =→∞

In this case, εi tends to infinity because the only price possible for a Bertrand producer

is the marginal cost. Else, a competitor would charge its marginal cost and the firm would

have no sales. The residual demand of any firm in this model under Bertrand is horizontal.

And as in perfect competition, firms will have no market power and no profits, and there

will be no welfare loss with respect to the competitive equilibrium.

The consumers’ surplus is:

CS = (a− d)a− d

2b

CS =(a− d)2

2b

And the welfare loss with respect to perfect competition is:

WL = 0

13

3.8 Summary

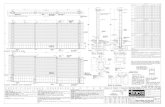

Graphically the results obtained in the model can be summarized as shown in figure

1:

Figure 1: Summary of the Results of the Model of Oligopoly

Source: author

A more detailed summary of the results is presented in table 1:

14

Table 1: Summary of the Results of the Oligopoly Model1

Market Collusion Threat Cournot Stackelberg Bertrand

qAa−d4b

a−d2b

a−d3b

a−d4b

a−d2b

qBa−d4b

0 a−d3b

(a−d)2b

a−d2b

Q a−d2b

a−d2b

2(a−d)3b

3(a−d)4b

a−db

p a+d2

a+d2

a+2d3

a+3d4

d

ΠA(a−d)2

8b(a−d)2

4b(a−d)2

9b(a−d)2

16b0

ΠB(a−d)2

8b0 (a−d)2

9b(a−d)2

8b0

Π (a−d)2

4b(a−d)2

4b2(a−d)2

9b3(a−d)2

16b0

MU a−da+d

a−da+d

a−da+2d

a−da+3d

0

ε a+da−d

a+da−d

a+2d2(a−d)

a+3d3(a−d)

da−d

εia+da−d

a+da−d

a+2d2(a−d)

a+3d3(a−d)

→∞

WL (a−d)2

8b(a−d)2

8b(a−d)2

18b(a−d)2

32b0

Source: author’s calculations

Within the simple model structure presented in this article, the algebraic results allow

us to conclude unambiguously, that, under the assumptions used:

Collusion and Threat replicate Monopoly, have the highest price; the lowest quantities

produced; the highest mark-up; the highest price elasticity of market demand; the highest

profits and the lowest welfare. When compared to Collusion, Cournot has a lower price;

higher total quantities produced; lower price elasticity of market demand; lower price

elasticity of residual demand; lower mark-up; lower profits and higher welfare. When

compared to Cournot, Stackelberg has a lower price; higher total equilibrium quantities;

lower price elasticity of market demand; lower price elasticity of residual demand; lower

mark-up; lower profits; and higher welfare. Bertrand has the lowest price; the highest

total equilibrium quantities; the lowest price elasticity of market demand, the highest

price elasticity of residual demand; the lowest mark-up; the lowest profits; and the highest

1The equilibria of Collusion and Bertrand are presented assuming the symmetric equilibrium.Given that there are no fixed costs, the equilibrium of Bertrand is identical to the equilibrium of PerfectCompetition, although in Perfect Competition there would be many firms.Note that given the assumptions of the model and in particular since a > 0, b > 0, d ≥ 0 and a > d, allthe results obtained are well defined.

15

welfare, when compared to any of the other conjectural variations considered in this

model, and replicates in this framework, the equilibrium that would prevail under perfect

competition.

Thus, in general, the conjectures with the lower prices have the higher equilibrium

quantities and vice-versa. These results are in line -and extend- those derived by Levin

(1988). The conjectures with the lower prices also have the higher welfare; the lower price

elasticity of market demand; the lower price elasticity of residual demand (except for the

price elasticity of residual demand in Bertrand); the lower mark-ups, the lower profits,

and vice-versa.

Note the counter-intuitive results regarding equilibria with lower mark-ups and lower

price elasticities of demand. However, both of these variables are endogenous in this

model and as such, this counter-intuitive results will be discussed in the next section of

this article.

4 Comparative Statics

The results presented in the previous sections, allow to perform comparative statics

that yield the following results:

4.1 All conjectures, except for Bertrand

In all conjectures except Bertrand, an increase in demand parameter a (an increase in

demand), leads to increases in equilibrium prices; output; profits; and mark-up. Increases

in a also lead to decreases in the price elasticity of market demand; the price elasticity of

residual demand; and welfare as compared to the welfare that would prevail under perfect

competition. And viceversa.

In these same conjectures, decreases in demand parameter b (an increase in demand),

lead to increases in equilibrium output and profits. The unit price; the mark-up; the

price elasticity of market demand; and the price elasticity of residual demand, remain

unchanged. Welfare would fall, as compared to the welfare that would prevail under

perfect competition. And viceversa.

16

In this scenario, decreases in the marginal cost d, at equilibrium, would lead to increases

in output, profits, and mark-up. Decreases in d would also lead to decreases in prices; the

price elasticity of market demand; the price elasticity of residual demand; and welfare,

when compared to the welfare under prefect competition. And viceversa.

As noted before, the results show -with the exception of the price elasticity of resid-

ual demand in Bertrand- a counter-intuitive positive correlation between mark-ups, and

the price elasticities of market demand and residual demand. However, in terms of the

parameters of the model and in particular, in terms of changes in the parameters a and

d, there is a negative correlation between mark-ups and price elasticities of demand, as is

standard in the economic literature.

4.2 Bertrand

In Bertrand, increases in demand (increases in a and/or decreases in b) or decreases

in the marginal cost d, lead to increases in output, with no changes in profits; mark-up;

the price elasticity of residual demand; or welfare -when compared to the welfare that

would prevail under perfect competition-. Decreases in the marginal cost would decrease

the unit price and the price elasticity of market demand. And viceversa.

Conclusions

This article has shown that given the model’s assumptions, when firms interact as in

Bertrand, they charge lower prices and have higher equilibrium quantities than when they

interact as in Stackelberg. When firms interact as in Stackelberg, they charge lower prices

and have higher equilibrium quantities than when they interact as in Cournot. And when

firms interact as in Cournot, they have lower prices and have higher equilibrium quantities

than when they collude.

In general, the conjectures with the lower prices have the the higher equilibrium quan-

tities; the higher welfare; the lower price elasticity of market demand; the lower residual

demand; the lower mark-ups, and the lower profits. viceversa.

In all conjectures except in Bertrand, increases in demand (as increases in a) and

17

decreases in the marginal cost, increase quantities; prices and mark-ups; and reduce welfare

when compared to perfect competition. Increases in demand (as decreases in b) also

increase quantities, mark-up and reduce welfare when compared to perfect competition.

In Bertrand, increases in demand (as increases in a) and decreases in marginal costs,

increase equilibrium quantities and reduce the price elasticity of market demand. Increases

in demand (as decreases in b) increase output. Decreases in marginal cost, decrease prices

and decrease the price elasticity of market demand. In Bertrand, none of the changes in

the parameters considered here alter the price elasticity of residual demand, the mark-up,

the profits, and welfare -when compared to the welfare under perfect competition-.

Although the results suggest in general, a positive -and counter-intuitive- correlation

between the mark up and the price elasticity of demand, these variables are endogenous

in this model. When the relevant parameters of the model change, there is a negative

correlation between these variables.

18

References

Bertrand, J., (1883), “Theorie Mathematique de la Richesse Sociale”,Journal des

Savants48: 499–508

Chamberlin, E. H. (1957) “On the Origin of ‘Oligopoly’”, The Economic Journal ,

Jun., 1957, Vol. 67, No. 266 (Jun., 1957), pp. 211-218, Oxford University Press

on behalf of the Royal Economic Society

Chamberlin, E. H. (1933), The Theory of Monopolistic Competition, Harvard Uni-

versity Press. d’Aspremont, C., Gabszewicz, J. J.and Thisse, J. F., (1979), “On

Hotelling’s ‘stability in competition’,Econometrica47: 1145–1150

Cournot, A. (1838),Recherches sur les Principes Mathematiques de la Theorie des

Richesses, Hachette, Paris

Edgeworth, F. Y. (1897) “La Teoria Pura del Monopolio” , Giornale degli Economisti

15: 13–31

Levin, D. (1988) “Stackelberg, Cournot And Collusive Monopoly: Performance An”,

Economic Inquiry; Apr; 26, 2; pg. 317

More, T. (1516/1967) “Utopia”, translated by Dolan, J. P. in Greene, J. J. and Dolan,

J. P. editors, The Essential Thomas More, New York: New American Library.

Shapiro, C. (1989) “Theories of Oligopoly Behavior” in Handbook of Industrial Or-

ganization, Elsevier, ch. 6, vol. 1, pp 329-414.

Vallejo, H. (2021) “Monopsony and minimum wages”, Documento CEDE No. 12.

19